“The Zine Age,” Artforum, March, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuli Kupferberg's Real Fake Real News

Tuli Kupferberg’s Real Fake Real News printmag.com/daily-heller/tuli-kupferbergs-real-fake-real-news/ Steven Heller 11/28/2017 In the early 1960s the emerging counterculture spawned by the Beats in New York City’s East Village began publishing a slew of what soon became known as “undergrounds.” Many of these cheaply printed publications followed in the Dada and Samizdat traditions. Some were known for raking the muck the mainstream media refused to print while others published real fake news that, paradoxically, turned out to be fake real news. YEAH magazine was originally published between 1961 and 1965 by Tuli Kupferberg (a founding member, with Ed Sanders, of the satiric rock band The Fugs) and Sylvia Topp’s Birth Press. Kupferberg, who created a few self-publishing ventures, called this “a satyric excursion; a sardonic review; a sarcastic epitome; a chronicle of the last days.” Like Paul Krassner‘s The Realist, YEAH threaded “the needle of leftist politics with the sarcasm and sharp creative wit for which he became known.” Now Primary Information, a nonprofit devoted to publishing artists’ books and artists’ writings, has reprinted YEAH‘s 10 ragtag issues. Although it contains no commentary, it is a welcome addition to the growing publishing literature of the era. Kupferberg and fellow East Village denizens contributed poetry, drawings and collages that protested nuclear war, racism, white supremacy, and the conservative, middle-class values that had become the hallmark of 1950s America. By issue 8, Kupferberg dispensed with contributors, choosing instead to feature only his own work. These later issues are very post-dada/pre-punk, with collages of images, illustrations, and articles appropriated from magazines and newspapers. -

The Fugs the Fugs II Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Fugs The Fugs II mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Fugs II Country: Italy Style: Folk Rock, Garage Rock, Psychedelic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1230 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1256 mb WMA version RAR size: 1777 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 584 Other Formats: DXD MP2 AIFF MMF RA AAC VOC Tracklist Hide Credits Frenzy A1 2:00 Written-By – Sanders* I Want To Know A2 2:00 Written-By – Olson*, Sanders* Skin Flowers A3 2:20 Written-By – Sanders*, Kearney* Group Grope A4 3:40 Written-By – Sanders* Coming Down A5 3:46 Written-By – Sanders* Dirty Old Man A6 2:49 Written-By – Sanders*, Goldbart* Kill For Peace B1 2:07 Written-By – Tuli Kupferberg Morning, Morning B2 2:07 Written-By – Tuli Kupferberg Doin' All Right B3 2:37 Written-By – Crabtree*, Berrigan*, Leary* Virgin Forest B4 11:09 Written-By – Sanders*, Crabtree*, Alderson* Credits Art Direction [Art Director] – Bert Glassberg Bass Guitar – John Anderson Design [Cover Design] – Bill Beckman Engineer – Richard L. Alderson* Guitar – Pete Kearney, Vinny Leary Harmony Vocals, Voice [Groans, Yelps, Ooos] – Betsy Klein, The Fugs Chorus* Liner Notes – Allen Ginsberg Mastered By – DBH* Percussion – Ken Weaver Photography By – Jim Nelson Piano, Celesta, Bells – Lee Crabtree Tambourine, Maracas – Tuli Kupferberg Vocals – Ed Sanders Notes Made in Italy by: BASE RECORD Via Collamarini 26, Bologna tel. 051-534697 - Telefax 051-538017 This release has different labels/ back cover. It is quite similar to these releases: The Fugs - The Fugs II The Fugs - The Fugs II The Fugs - The -

The Ed Sanders Archive Including the Fugs, Peace Eye Bookstore, Fuck You/ a Magazine of the Arts, Allen Ginsberg, D.A

The Ed Sanders Archive Including the Fugs, Peace Eye Bookstore, Fuck You/ A Magazine of the Arts, Allen Ginsberg, d.a. levy, Claude Pélieu, and John Sinclair Ed Sanders backstage at the Fillmore East with his friend Janis Joplin, March 8, 1968. Introduction The Ed Sanders Archive is a remarkable record of the legendary poet, writer, editor, publisher, activist, Fugs founder and icon of American counterculture. Beginning with his first poems written while he still lived in Missouri (1955), it encompasses all of Sanders’ expansive life and career. The archive is a unique resource that allows for the exploration into Sanders’ seminal contributions to the Mimeo Revolution and American poetry, as well as his legacy in the American underground and counterculture with his political activism and his music. The archive itself has long been spoken of by scholars as well as fans. Sanders organized the archive over a 10-year period. Due to its size it is housed in multiple buildings and locations at his and his wife Miriam’s home in Woodstock, NY, where they have lived since 1974. [Unless otherwise noted all quotes are from Ed Sanders’ Fug You: An Informal History of the Peace Eye Bookstore, the Fuck You Press, the Fugs, and Counterculture in the Lower East Side (De Capo Press, 2011). Along with Ed Sanders’ notes, Fug You served as the primary source for other information in the archive’s prospectus.] Archive Contents Biography Archive Summary Archive Highlights The Fugs Peace Eye Bookstore Fuck You Press Friends Allen Ginsberg d.a. levy Claude Pélieu John Sinclair Spain Rodriguez Writing & Projects Poetry Glyphs Musical Instruments Manson Family Olson Lectures Chronological Boxes Activism & Assorted Ed Sanders Biography Left: Ed Sanders “flashing a mudra” taught to him by Allen Ginsberg in 1964. -

Download the Fugs First Album the Fugs

download the fugs first album The Fugs. The Fugs were a band formed in New York City in 1965 by Ed Sanders and Tuli Kupferberg, with Ken Weaver on drums. Later that year they were joined by Peter Stampfel and Steve Weber of the Holy Modal Rounders. The band was named by Kupferberg who borrowed it from the euphemistic substitute for the word "fuck" famously used in Norman Mailer's novel, The Naked and the Dead. Incidentally, the band is featured in a chapter of Mailer's book, Armies of the Night as they play at the 1967 march on the Pentagon in protest of the Vietnam War (with Scott Rashap on upright bass). The band was named by Kupferberg who borrowed it from the euphemistic substitute for the word "fuck" famously used in Norman Mailer's novel, The Naked and the Dead. Incidentally, the band is featured in a chapter of Mailer's book, Armies of the Night as they play at the 1967 march on the Pentagon in protest of the Vietnam War (with Scott Rashap on upright bass). The Fugs were a satirical and self-satirizing rock band that performed at protests against the Vietnam War nationwide. Their 1968 Transatlantic Records album "It crawled into my hand, honest" (TRA 181) also helped to make them more widely known on the European side of the Atlantic. (This album is now also available as tracks 11 to 30 of "Electromagnetic Steamboat") The band's frank lyrics about sex, drugs, and politics aroused a hostile reaction in some quarters, and enthusiastic interest in others. -

Beat Contenders (Micheline, Sanders, Kupferberg)

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 18 (2016) Issue 5 Article 2 Beat Contenders (Micheline, Sanders, Kupferberg) A. Robert Lee Independent Scholar Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the -

A History of the East Village and Its Architecture

A History of the East Village and Its Architecture by Francis Morrone with chapters by Rebecca Amato and Jean Arrington * December, 2018 Commissioned by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East Eleventh Street New York, NY 10003 Report funded by Preserve New York, a grant program of the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East Eleventh Street, New York, NY 10003 212-475-9585 Phone 212-475-9582 Fax www.gvshp.org [email protected] Board of Trustees: Arthur Levin, President Trevor Stewart, Vice President Kyung Choi Bordes, Vice President Allan Sperling, Secretary/Treasurer Mary Ann Arisman Tom Birchard Dick Blodgett Jessica Davis Cassie Glover David Hottenroth Anita Isola John Lamb Justine Leguizamo Leslie Mason Ruth McCoy Andrew Paul Robert Rogers Katherine Schoonover Marilyn Sobel Judith Stonehill Naomi Usher Linda Yowell F. Anthony Zunino, III Staff: Andrew Berman, Executive Director Sarah Bean Apmann, Director of Research and Preservation Harry Bubbins, East Village and Special Projects Director Ariel Kates, Manager of Programming and Communications Matthew Morowitz, Program and Administrative Associate Sam Moskowitz, Director of Operations Lannyl Stephens, Director of Development and Special Events The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation was founded in 1980 to preserve the architectural heritage and cultural history of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo. /gvshp /gvshp_nyc www.gvshp.org/donate Acknowledgements This report was edited by Sarah Bean Apmann, GVSHP Director of Research and Preservation, Karen Loew, and Amanda Davis. This project is funded by Preserve New York, a grant program of the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts. -

Alog Strictly Devoted to the Subject

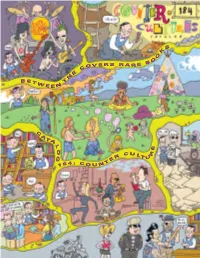

S K O OV E R S O C O S R A B C R E E H BB EE H TT T WW T EE EE NN CC AA T T AA LL O O G G E U E C U L R R E T 1188 44 :: CC E U OO UU NN TT COUNTERCULTURE: INTRODUCTION “The art of the Culture is to preserve order amid change; the art of the Counter Culture is to preserve change amid order.” – anonymous bookseller, possibly (or probably) plagiarized from someone else What is the Counter Culture? Although BTC has been dealing in Counter Cultural material pretty much since we’ve existed as an entity, we’ve never issued a catalog strictly devoted to the subject. When we started in the mid 1980s, some of the “Cultures” whose artifacts we’re now dealing in didn’t even exist. This goes to show, I guess, that the definition of Counter Culture is constantly evolving. I asked Ken Giese on our staff to define Counter Culture in ten seconds. Go! - “Arggghhh, hippies, it was the hippies, it was always the hippies for me!” Similarly incoherent responses were received from others on our staff, although Ashley Wildes well-considered “What?” stands out. Matt Histand probably did best when he said it was “Anything that youth was rebelling against that has since become part of the culture.” Obviously much of one’s perspective on this is or can be generational. And indeed the friction created by the interaction of the generations might actually be the proper definition. -

Be Free— the Fugs Final CD (Part 2)

Lyrics for Be Free— The Fugs Final CD (Part 2) 1. Be Free Ed Sanders, Steve Taylor, Coby Batty, Musical arrangement by Scott Petito 3:42 2. Backward Jewish Soldiers Tuli Kupferberg, Arthur Sullivan 3:36 3. My Darling Magnolia Tree Coby Batty, Ed Sanders 3:33 4. Goofitude Ed Sanders 2:55 5. This is a Hit Song Tuli Kupferberg 2:22 6. The Laughing Song William Blake, Ed Sanders —dedicated to Meredith Monk 2:38 7. Hungry Blues Steve Taylor 4:29 8. Loose Peach Gown Ed Sanders 2:50 9. Bartleby the Scrivener Ed Sanders —adapted from a story by Melville 6:08 10. ImGrat Ed Sanders 3:44 11. The CIA Made Me Sing Off-Key Ed Sanders 3:40 12. The British Journalist Humbert Wolf, Tuli Kupferberg 1:48 13. I Am An Artist for Art’s Sake Tuli Kupferberg 3:29 14. Greenwich Village of My Dreams words: Tuli Kupferberg music: Scott Petito 4:42 1 Be Free —Scott Petito, Coby Batty, Steve Taylor, Ed Sanders Roll up your woes woh woh woh! No time to fold it up Come on people, let’s go Hold on to your brothers & your sisters We’re all Fugs now We’re all Fugs now What’s gone? Democracy, said William Burroughs No one asked him ’fore they dropped the bomb. What’s left? Rock and roll music The song of the poet goes on and on The song of the poet goes on and on and on and on and on Be Free Be Free Be Free Be Free Be Free I walked around the country mile after mile So many in jail for pot or lifestyle Be Free Act Free Talk Free Think Free Roll up your woes woh woh woh! No time to fold it up Come on people, let’s go Hold on to your brothers & your sisters We’re all Fugs now We’re all Fugs now What’s gone? Democracy, said William Burroughs No one asked him ’fore they dropped the bomb. -

Catalog 164 Mimeographs

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 164 Mimeographs 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All items are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2010 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com The Mimeograph Revolution A few years ago we purchased a collection impossible to assemble. that contained a sizable number of mimeograph and literary magazines. We For the sake of this catalogue the mimeos naturally did what any good bookseller and literary magazines are divided into would do. We pulled out the books and three periods for easier reference. The ignored the rest. Well, that’s a bit of dates below may seem arbitrary, but I an overstatement. Certainly a few of the believe movements have a way of defining magazines were cataloged but most were themselves. -

Kenneth Goldsmith

6799 Kenneth Goldsmith zingmagazine 2000 for Clark Coolidge 45 John Cage 42 Frank Zappa / Mothers 30 Charles Ives 28 Miles Davis 26 James Brown 25 Erik Satie 24 Igor Stravinsky 23 Olivier Messiaen 23 Neil Young 23 Kurt Weill 21 Darius Milhaud 21 Bob Dylan 20 Rolling Stones 19 John Coltrane 18 Terry Riley 18 Morton Feldman 16 Rod McKuen 15 Thelonious Monk 15 Ray Charles 15 Mauricio Kagel 13 Duke Ellington 3 A Kombi Music to Drive By, A Tribe Called Quest M i d n i g h t Madness, A Tribe Called Quest People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, A Tribe Called Quest The Low End Theory, Abba G reatest Hits, Peter Abelard Monastic Song, Absinthe Radio Trio Absinthe Radio Tr i o, AC DC Back in Black, AC DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, AC DC Flick of the Switch, AC DC For Those About to Rock, AC DC Highway to Hell, AC DC Let There Be R o c k, Johnny Ace Again... Johnny Sings, Daniel Adams C a g e d Heat 3000, John Adams Harmonium, John Adams Shaker Loops / Phrygian Gates, John Luther Adams Luther Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing, King Ade Sunny Juju Music, Admiral Bailey Ram Up You Party, Adventures in Negro History, Aerosmith Toys in the Attic, After Dinner E d i t i o n s, Spiro T. Agnew S p e a k s O u t, Spiro T. Agnew The Great Comedy Album, Faiza Ahmed B e s a r a h a, Mahmoud Ahmed E re Mela Mela, Akita Azuma Haswell & Sakaibara Ich Schnitt Mich In Den Finger, Masami Akita & Zbigniew Karkowski Sound Pressure Level, Isaac Albéniz I b e r i a, Isaac Albéniz Piano Music Volume II, Willy Alberti Marina, Dennis Alcapone Forever Version, Alive Alive!, Lee Allen Walkin’ with Mr. -

Beats and Friends: a Check-List of Audio-Visual Material in the British Library

BEATS AND FRIENDS: A CHECK-LIST OF AUDIO-VISUAL MATERIAL IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelprestype/sound/literature/literaturesound.html CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 3 WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS ..................................................................................... 5 ALLEN GINSBERG ................................................................................................ 16 JACK KEROUAC................................................................................................... 26 THE EAST COAST SCENE..................................................................................... 29 John Ashbery................................................................................................ 29 Amiri Baraka................................................................................................. 30 Ted Berrigan................................................................................................. 32 Kenward Elmslie ........................................................................................... 33 The Fugs....................................................................................................... 33 John Giorno.................................................................................................. 35 Ted Joans ..................................................................................................... 35 Leroi Jones................................................................................................... -

Yeah, Yeah, Yeah

Yeah, Yeah, Yeah lrb.co.uk/blog/2017/12/15/alex-abramovich/yeah-yeah-yeah/ Alex Abramovich Tuli Kupferberg and Ed Sanders met in New York City in 1962, in front of the Charles Theater, two blocks north of Tompkins Square Park. Kupferberg was selling issues of Birth, a mimeographed publication he’d started in the 1950s. Sanders, who’d just launched his own mimeographed magazine, knew a few things about him. ‘I’d seen his picture in a number of books,’ Sanders later recalled. ‘I learned a little bit later that he was the guy “who’d jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge”, as described in Howl. (Actually it was the Manhattan Bridge.) I later asked him why. He replied, “I wasn’t being loved enough.”’ A few years later, Sanders and Kupferberg formed the Fugs. They paid homage to Allen Ginsberg and Howl with a song called ‘The Best Minds of My Generation Rock’, played together for a few more years, broke up, and reformed, from time to time, as the years and decades went by. The third founding member, Ken Weaver, went on to work as a translator for the CIA and other government agencies. The Fugs were loved. In 2007, Printed Matter mounted an exhibition – Fuck For Peace: A History of the Fugs – that doubled as a history of New York in the 1960s, and of a certain, scabrous sensibility that continues to inform and (one hopes) autocorrect the national psyche. This year, it published a facsimile edition of Yeah, a mimeographed magazine Kupferberg put out in the early 1960s, and sold for 25 cents.