Privately-Funded Public Housing Redevelopment: a Study of the Transformation of Columbia Point (Boston, MA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Request for Tenancy Approval – Owner Information

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Phone: 617-988-4000 Leased Housing Fax: 617-988-4147 52 Chauncy Street, Floors 1, 4, & 5 TDD: 800-545-1833 x420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111 www.BostonHousing.org Request for Tenancy Approval – Owner Information Please read the following regarding the Boston Housing Authority tenancy approval process. An understanding of the following process will help to ensure prompt receipt of housing assistance payments: 1. Complete the enclosed Relocation Package. 2. In addition to the completed package, you must also provide: Management Agreement: A current management agreement or letter from the owner authorizing the management company or property manager to conduct business on behalf of the owner, if applicable. The BHA has a Model Lease that you may utilize for the Section 8 tenancy. However, if you decide to use your own lease, you must submit it for BHA review. Water Sub-metering Form: If you wish to charge the tenant for water, you must provide a valid sub-metering form and a lease addendum for billing water utility. 3. Contact the BHA Inspection Department approximately three (3) business days after submitting a completed RFTA. Contact the inspections department by calling (617) 522- 0048. 4. The unit and any common areas must pass inspection prior to lease-up. The unit must be vacant to conduct an inspection. Typically, an inspection prior to the 20th of the month will result in a lease effective date on the 1st of the following month. 5. The BHA now requires Direct Deposit to receive payment. The Direct Deposit form and a W-9 will be collected by the Owner Services team during the Leasing Process. -

Boston Housing Authority (Bha) – Preliminary

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY (BHA) – PRELIMINARY APPLICATION FOR HOUSING I wish to apply for the public housing program (check one or both and complete the choice forms): Name of Head of Household (please print) (Note: must be 18 years old or emancipated minor) □ Family Public Housing ! □ Elderly/Disabled Public Housing: to qualify for this program, 246 First MI Last you must be 60 years of age or older for the state programs, and Name of Co-Head of Household (Note: must be 18 years old or emancipated minor and will have equal rights to the application) 62 or older for federal programs, or disabled as defined by the = Social Security Administration or federal regulations. - First MI Last To apply for the following Section 8 programs, you must = Mailing Address qualify as a Priority One Applicant as of the date you apply. ! (Check one or both and complete the choice forms): □Housing Choice Voucher (Section 8) Mod Rehab # Street Apt # □Housing Choice Voucher (Section 8) Project-Based X Housing Choice Voucher (Section 8) Tenant- Based is closed. City State Zip Code Address where currently residing Language Spoken: ________________________ Language Read: ___________________________ (if different from above): ________________________________________________________________ Day time Phone: (_____) ______ – ___________ Evening Phone: (_____) ______ – ____________ Household Composition. Request an additional page if you will have more than 5 household members. Please list all individuals who will live with you if housed with the BHA. For the elderly/disabled housing program, household size can not exceed the number of persons who could legally occupy a two bedroom apartment. Relationship Sex Date of Birth Disabled Race– Hispanic/Latino? US Citizen, If No, Alien Income Annual Gross Value of First Name MI Last Name To Head M/F Mo/Day/Year Age Social Security # Yes/No See Codes* Yes/No Yes/No Registration # Source** Income Assets 1 Head / / 2 Co-Head / / 3 / / 4 / / 5 / / Please answer the following questions: If the response is not applicable write N/A 1. -

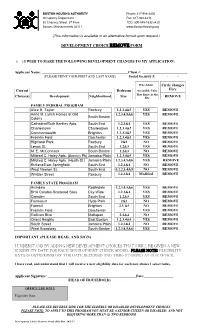

DEVELOPMENT CHOICE ADD FORM (Public Housing) IMPORTANT

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Phone: 617-988-3400 Occupancy Department Fax: 617-988-4214 52 Chauncy Street, 3rd Floor TDD: 800-545-1833 x420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111 www.BostonHousing.org (This information is available in an alternative format upon request.) DEVELOPMENT CHOICE ADD FORM (Public Housing) ( ) I WISH TO MAKE THE FOLLOWING DEVELOPMENT CHANGES TO MY APPLICATION: Applicant Name: ________________________________________________Client #: _________________________ (PLEASE PRINT YOUR FIRST AND LAST NAME) Social Security #: - - Wheelchair Circle Changes Current Bedroom Accessible Units Here Choice(s) Development Neighborhood Size That Exist At the Site ADD FAMILY FEDERAL PROGRAM Alice H. Taylor Roxbury 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Anne M. Lynch Homes at Old 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES ADD South Boston Colony Cathedral South End 1,2,3&4 YES ADD Charlestown Charlestown 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Commonwealth Brighton 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Franklin Field Dorchester 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Highland Park Roxbury 2&3 NO ADD Lenox St. South End 1,2&3 YES ADD M. E. McCormack South Boston 1,2&3 NO ADD Mildred C. Haley Apts.(Bromley Pk.) Jamaica Plain 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Mildred C. Haley Apts. (Heath St.) Jamaica Plain 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES ADD Rutland/East Springfield South End 1,2,3&4 NO ADD West Newton St. South End 0,1,2,3,4&5 NO ADD Whittier Street Roxbury 1,2,3&4 Modified ADD FAMILY STATE PROGRAM Archdale Roslindale 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES ADD BHA Condos-Scattered Sites City-Wide 1,2,3&4 YES ADD Camden South End 1,2&3 YES ADD Fairmount Hyde Park 2&3 NO ADD Faneuil Brighton 2,3,&5 NO ADD Franklin Field Dorchester 2 YES ADD Gallivan Blvd. -

Public Housing Waiting List Update

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Phone: 617-988-3400 Occupancy Department Fax: 617-988-4214 56 Chauncy Street, 1st Floor TDD: 800-545-1833 x420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111 www.BostonHousing.org (This information is available in an alternative format upon request.) HOUSING CHOICE VOUCHER PROJECT BASED PROGRAMS CHOICE CHANGE ADD FORM Name: _________________________________________ SS#: ______________________________ IA. ELDERLY/DISABLED HOUSING CHOICE VOUCHER PROGRAM PROJECT-BASED SITES Note: Be advised, the Head or Co-Head must be Elderly (62 years or age or older) or Disabled AND must qualify as a Priority One Applicant in order to apply for the Sites listed below. Check Box () Site Name Neighborhood Bedroom Wheelchair Circle Size (s) Access? Here Algonquin- Supported Housing Dorchester SRO Yes Add SRO, Studio, 1 Yes Add Ashford Street Lodging Allston Boston Hope Dorchester 1, 2 Yes Add Boston SRO Yes Add Bowdoin Manor- Supported Housing Brighton Studio Yes Add Corey Seton Manor-Supported Housing Egleston Crossing Roxbury 1, 2 No Add Jamaica Plain SRO Yes Add Green Street – Supported Housing Jamaica Plain SRO Yes Add Hearth at Burroughs LLC- Supported Housing Dorchester 1 Yes Add Hearth at Olmsted Green – Supported Housing Imani House Dorchester Studio,1 Yes Add Mattapan Studio, 1 Yes Add The Foley- Supported Housing Uphams Corner – Supported Housing Dorchester Studio Yes Add Walnut House Roxbury Studio Yes Add Boston SRO Yes Add Washington Street – Supported Housing Ziegler- Supported Housing Boston SRO No Add IB. ELDERLY/DISABLED HOUSING CHOICE VOUCHER PROGRAM PROJECT-BASED SITES Note: Be advised, the Head or Co-Head must be Elderly (62 years or age or older) or Disabled in order to apply for the Sites listed below. -

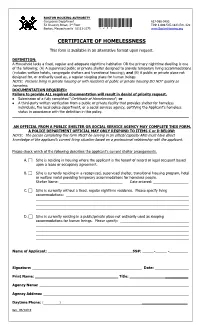

Homelessness-Priority-Certificate.Pdf

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Occupancy Department 617-988-3400 52 Chauncy Street, 3rd Floor TDD 1-800-545-1833 Ext. 420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111-2375 !255=-==! www.BostonHousing.org CERTIFICATE OF HOMELESSNESS This form is available in an alternative format upon request. DEFINITION: A Household lacks a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime habitation OR the primary nighttime dwelling is one of the following; (A) A supervised public or private shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations (includes welfare hotels, congregate shelters and transitional housing); and (B) A public or private place not designed for, or ordinarily used as, a regular sleeping place for human beings. NOTE: Persons living in private housing or with residents of public or private housing DO NOT qualify as homeless. DOCUMENTATION REQUIRED: Failure to provide ALL required documentation will result in denial of priority request. Submission of a fully completed “Certificate of Homelessness”; or A third-party written verification from a public or private facility that provides shelter for homeless individuals, the local police department, or a social services agency, certifying the Applicant's homeless status in accordance with the definition in this policy. AN OFFICIAL FROM A PUBLIC SHELTER OR SOCIAL SERVICE AGENCY MAY COMPLETE THIS FORM. A POLICE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL MAY ONLY RESPOND TO ITEMS C or D BELOW: NOTE: The person completing this form MUST be serving in an official capacity AND must have direct knowledge of the applicant's current living situation based on a professional relationship with the applicant. Please check which of the following describes the applicant's current shelter arrangements. -

Development Choice Remove Form

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Phone: 617-988-3400 Occupancy Department Fax: 617-988-4214 52 Chauncy Street, 3rd Floor TDD: 800-545-1833 x420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111 www.BostonHousing.org (This information is available in an alternative format upon request.) DEVELOPMENT CHOICE REMOVE FORM ( ) I WISH TO MAKE THE FOLLOWING DEVELOPMENT CHANGES TO MY APPLICATION: Applicant Name: ________________________________________________Client #: _________________________ (PLEASE PRINT YOUR FIRST AND LAST NAME) Social Security #: - - Wheelchair Circle changes Current Bedroom Accessible Units Here That Exist At the Choice(s) Development Neighborhood Size Site REMOVE FAMILY FEDERAL PROGRAM Alice H. Taylor Roxbury 1,2,3,4&5 YES REMOVE Anne M. Lynch Homes at Old 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES REMOVE Colony South Boston Cathedral/Ruth Barkley Apts. South End 1,2,3&4 YES REMOVE Charlestown Charlestown 1,2,3,4&5 YES REMOVE Commonwealth Brighton 1,2,3,4&5 YES REMOVE Franklin Field Dorchester 1,2,3,4&5 YES REMOVE Highland Park Roxbury 2&3 NO REMOVE Lenox St. South End 1,2&3 YES REMOVE M. E. McCormack South Boston 1,2&3 NO REMOVE Mildred C. Haley Apts. (Bromley Pk) Jamaica Plain 1,2,3,4&5 YES REMOVE Mildred C. Haley Apts. (Heath St.) Jamaica Plain 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES REMOVE Rutland/East Springfield South End 1,2,3&4 NO REMOVE West Newton St. South End 0,1,2,3,4&5 NO REMOVE Whittier Street Roxbury 1,2,3&4 Modified REMOVE FAMILY STATE PROGRAM Archdale Roslindale 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES REMOVE BHA Condos-Scattered Sites City-Wide 1,2,3&4 YES REMOVE Camden South End 1,2&3 YES REMOVE Fairmount Hyde Park 2&3 NO REMOVE Faneuil Brighton 2,3,&5 NO REMOVE Franklin Field Dorchester 2 YES REMOVE Gallivan Blvd Mattapan 2,3&4 NO REMOVE Orient Heights East Boston 1,2,3,4&5 YES REMOVE South Street Jamaica Plain 1,2,3&4 NO REMOVE West Broadway South Boston 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES REMOVE IMPORTANT (PLEASE READ, AND SIGN) I UNDERSTAND BY ADDING NEW DEVELOPMENT CHOICES THAT I WILL BE GIVEN A NEW ELIGIBILITY DATE FOR EACH DEVELOPMENT CHOICE ADDED. -

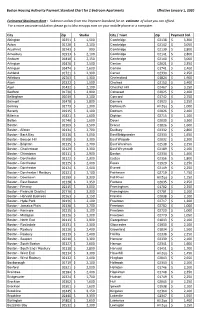

2020 Payment Standards Effective January 1.Xlsx

Boston Housing Authority Payment Standard Chart for 2 Bedroom Apartments Effective January 1, 2020 Estimated Maximum Rent : Subtract utilites from the Payment Standard for an estimate of what you can afford. For a more accurate calulation please go to bha.cvrapps.com on your mobile phone or a computer. City Zip Studio City / Town Zip Payment Std. Abington 02351 $ 1,500 Cambridge 02138 $ 3,300 Acton 01720 $ 2,100 Cambridge 02142 $ 3,050 Acushnet 02743 $ 900 Cambridge 02139 $ 2,800 Amesbury 01913 $ 2,100 Cambridge 02141 $ 2,800 Andover 01810 $ 2,150 Cambridge 02140 $ 3,000 Arlington 02476 $ 2,500 Canton 02021 $ 2,350 Arlington 02474 $ 2,600 Carlisle 01741 $ 2,400 Ashland 01721 $ 2,300 Carver 02330 $ 2,250 Attleboro 02703 $ 1,300 Chelmsford 01824 $ 1,900 Avon 02322 $ 1,500 Chelsea 02150 $ 2,400 Ayer 01432 $ 2,100 Chestnut Hill 02467 $ 3,150 Bedford 01730 $ 2,900 Cohasset 02025 $ 2,400 Bellingham 02019 $ 2,100 Concord 01742 $ 2,750 Belmont 02478 $ 2,800 Danvers 01923 $ 2,250 Berkley 02779 $ 1,300 Dartmouth All Zips $ 1,000 Beverly 01915 $ 2,100 Dedham 02026 $ 2,400 Billerica 01821 $ 1,600 Dighton 02715 $ 1,100 Bolton 01740 $ 1,600 Dover 02030 $ 3,300 Boston 02109 $ 3,500 Dracut 01826 $ 1,600 Boston - Allston 02134 $ 2,700 Duxbury 02332 $ 2,800 Boston - Back Bay 02116 $ 3,050 East Bridgewater 02333 $ 1,650 Boston - Beacon Hill 02108 $ 3,300 East Walpole 02032 $ 2,200 Boston - Brighton 02135 $ 2,700 East Wareham 02538 $ 2,250 Boston - Charlestown 02129 $ 3,300 East Weymouth 02189 $ 2,100 Boston - Chinatown 02111 $ 2,900 Easton 02334 $ 1,400 -

Public Housing Waiting List Update

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Phone: 617-988-3400 Occupancy Department Fax: 617-988-4214 56 Chauncy Street, 1st Floor TDD: 800-545-1833 x420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111 www.BostonHousing.org (This information is available in an alternative format upon request.) HOUSING CHOICE VOUCHER PROJECT BASED PROGRAMS CHOICE CHANGE REMOVE FORM Name: _________________________________________ SS#: ______________________________ IA. ELDERLY/DISABLED HOUSING CHOICE VOUCHER PROGRAM PROJECT-BASED SITES Note: Be advised, the Head or Co-Head must be Elderly (62 years or age or older) or Disabled AND must qualify as a Priority One Applicant in order to apply for the Sites listed below. Check Box () Site Name Neighborhood Bedroom Wheelchair Circle Size (s) Access? Here SRO, Studio, 1 Yes Remove Ashford Street Lodging Allston Boston Hope Dorchester 1, 2 Yes Remove Boston SRO Yes Remove Bowdoin Manor- Supported Housing Brighton Studio Yes Remove Corey Seton Manor-Supported Housing Egleston Crossing Roxbury 1, 2 No Remove Jamaica Plain SRO Yes Remove Green Street – Supported Housing Jamaica Plain SRO Yes Remove Hearth at Burroughs LLC- Supported Housing Dorchester 1 Yes Remove Hearth at Olmsted Green – Supported Housing Imani House Dorchester Studio,1 Yes Remove Rutland Square House Boston 2 Yes Remove Mattapan Studio, 1 Yes Remove The Foley- Supported Housing Uphams Corner – Supported Housing Dorchester Studio Yes Remove Walnut House Roxbury Studio Yes Remove Boston SRO Yes Remove Washington Street – Supported Housing Ziegler- Supported Housing Boston SRO No Remove IB. ELDERLY/DISABLED HOUSING CHOICE VOUCHER PROGRAM PROJECT-BASED SITES Note: Be advised, the Head or Co-Head must be Elderly (62 years or age or older) or Disabled in order to apply for the Sites listed below. -

Public Housing Waiting List Update

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Phone: 617-988-3400 Occupancy Department Fax: 617-988-4214 56 Chauncy Street, 1st Floor TDD: 800-545-1833 x420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111 www.BostonHousing.org (This information is available in an alternative format upon request.) DEVELOPMENT CHOICE ADD FORM (Public Housing) ( ) I WISH TO MAKE THE FOLLOWING DEVELOPMENT CHANGES TO MY APPLICATION: Applicant Name: ________________________________________________Client #: _________________________ (PLEASE PRINT YOUR FIRST AND LAST NAME) Social Security #: - - Wheelchair Circle Changes Current Bedroom Accessible Units Below Choice(s) Development Neighborhood Size That Exist At the Site Check Box FAMILY FEDERAL PROGRAM () Alice H. Taylor Roxbury 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Anne M. Lynch Homes at Old 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES ADD South Boston Colony Cathedral/Ruth Barkley Apts. South End 1,2,3&4 YES ADD Charlestown Charlestown 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD nyCommonwealth Brighton 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Franklin Field Dorchester 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD Highland Park Roxbury 2&3 NO ADD Lenox Street South End 1,2&3 YES ADD Mary Ellen McCormack South Boston 1,2&3 NO ADD Mildred C. Haley Apts. (Bromley Pk) Jamaica Plain 1,2,3,4&5 YES ADD PMildred k.) C. Haley Apts. (Heath St.) Jamaica Plain 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES ADD Check FAMILY STATE PROGRAM Box () Archdale Roslindale 1,2,3,4,5&6 YES ADD BHA Condos-Scattered Sites City-Wide 1,2,3&4 YES ADD Fairmount Hyde Park 2&3 NO ADD Faneuil Brighton 2,3,&5 NO ADD Franklin Field Dorchester 2 YES ADD Gallivan Blvd. -

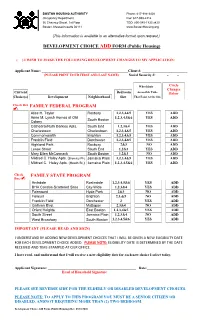

2021-Payment-Standards-Boston.Pdf

Boston Housing Authority Payment Standard Chart for All Bedroom Sizes Effective January 1, 2021 City Zip SRO 0 BR 1BR 2BR 3BR 4BR 5BR 6BR Abington 02351$ 775 $ 1,050 $ 1,200 $ 1,500 $ 1,900 $ 2,200 $ 2,525 $ 2,850 Acton 01720$ 1,175 $ 1,550 $ 1,725 $ 2,100 $ 2,625 $ 2,850 $ 3,275 $ 3,700 Acushnet 02743$ 550 $ 725 $ 800 $ 900 $ 1,125 $ 1,225 $ 1,400 $ 1,600 Amesbury 01913$ 1,175 $ 1,550 $ 1,725 $ 2,100 $ 2,625 $ 2,850 $ 3,275 $ 3,700 Andover 01810$ 1,225 $ 1,575 $ 1,775 $ 2,150 $ 2,700 $ 2,900 $ 3,325 $ 3,775 Arlington 02474$ 1,450 $ 1,925 $ 2,125 $ 2,600 $ 3,225 $ 3,525 $ 4,100 $ 4,600 Arlington 02476$ 1,400 $ 1,850 $ 2,050 $ 2,500 $ 3,125 $ 3,375 $ 3,900 $ 4,400 Ashland 01721$ 1,275 $ 1,700 $ 1,900 $ 2,300 $ 2,875 $ 3,125 $ 3,575 $ 4,050 Attleboro 02703$ 725 $ 950 $ 1,075 $ 1,300 $ 1,625 $ 1,925 $ 2,200 $ 2,500 Avon 02322$ 775 $ 1,050 $ 1,275 $ 1,500 $ 1,900 $ 2,200 $ 2,525 $ 2,850 Ayer 01432$ 1,175 $ 1,550 $ 1,725 $ 2,100 $ 2,625 $ 2,850 $ 3,275 $ 3,700 Bedford 01730$ 1,600 $ 2,150 $ 2,400 $ 2,900 $ 3,600 $ 3,925 $ 4,525 $ 5,125 Bellingham 02019$ 1,175 $ 1,550 $ 1,725 $ 2,100 $ 2,625 $ 2,850 $ 3,275 $ 3,700 Belmont 02478$ 1,550 $ 2,075 $ 2,300 $ 2,800 $ 3,475 $ 3,800 $ 4,375 $ 4,925 Berkley 02779$ 650 $ 850 $ 1,025 $ 1,300 $ 1,675 $ 1,850 $ 2,125 $ 2,400 Beverly 01915$ 1,175 $ 1,550 $ 1,725 $ 2,100 $ 2,625 $ 2,850 $ 3,275 $ 3,700 Billerica 01821$ 1,000 $ 1,325 $ 1,475 $ 1,800 $ 2,250 $ 2,425 $ 2,800 $ 3,150 Bolton 01740$ 900 $ 1,200 $ 1,200 $ 1,600 $ 2,000 $ 2,500 $ 2,900 $ 3,200 Boston 02109$ 1,950 $ 2,600 $ 2,875 $ 3,500 $ 4,350 $ -

J~ 2Lifecommunities O Age Affordably

J~ 2LifeCOMMUNITIES o Age affordably. Live well. C~4 FormerlyJewish Community Housingfor the Elderly (JCHE) LLI September 11, 2019 Brian P. Golden, Director Boston Planning & Development Agency One City Hall Square Boston, MA 02201 Re: Letter of Intent to File Project Notification Form (“PNF”) J.J. Carroll Redevelopment 130 Chestnut Hill Aye, Brighton Neighborhood District Dear Director Golden, This letter serves as the Letter of Intent pursuant to the Executive Order entitled: “An Order Relative to the Provision of Mitigation by Development Projects in Boston” with respect to the J.J. Carroll Redevelopment project (“Proposed Project”) located as 130 Chestnut Hill Avenue in Brighton proposed by 2 Life Communities (“2 Life”), formerly known as Jewish Community Housing for the Elderly (“JCHE”). The John J. Carroll Apartments were developed by the Boston Housing Authority (“BHA”) in 1966 and currently consist of 64 public housing units and an approximately 1,600 square foot (“sf’) Community Room. J.J. Carroll is adjacent to 2 Life’s four existing buildings in Brighton, which include 763 apartments of independent affordable senior housing with services and an array of community spaces such as a fitness center, library, computer center, dining room, and numerous multi-purpose spaces. Our Brighton community in particular is a rich hub of activity where nearly 1,000 residents have access to a multi lingual Resident Services team, 24/7 emergency response, fitness/wellness programs, lifelong learning, intergenerational programs, arts and culture events, and countless other programs and services, and we are excited to make all of this available to the J.J. -

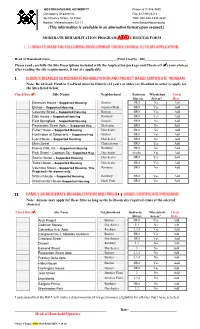

Add Choice(S) Form

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Phone: 617-988-3400 Occupancy Department Fax: 617-988-4214 56 Chauncy Street, 1st Floor TDD: 800-545-1833 x420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111 www.BostonHousing.org (This information is available in an alternative format upon request.) MODERATE REHABILITATION PROGRAM ADD CHOICE(S) FORM Head of Household Name________________________________________ (Print Clearly) SS#_________________________ Please read carefully the Site Descriptions included with the Application package and Check-off () your choices after reading the site requirements, if any are applicable. I. Note: Be advised, Head or Co-Head must be Elderly (62 years or older) or Disabled in order to apply for the Sites listed below. Check Box () Site Name Neighborhood Bedroom Wheelchair Circle Size (s) Access? Here Betances House - Supported Housing Boston SRO No Add Bishop – Supported Housing Jamaica Plain SRO Yes Add Coventry Street – Supported Housing Boston SRO Yes Add Daly House – Supported Housing Roxbury SRO Yes Add East Springfield – Supported Housing Boston SRO No Add Fessenden Street Apts. – Supported Hsg. Mattapan SRO No Add Fuller House – Supported Housing Dorchester SRO No Add Huntington at Symphony – Supported Hsg. Boston SRO Yes Add Lyon House – Supported Housing Dorchester SRO No Add Main Street Charlestown SRO Yes Add Nueva Vida, Inc. – Supported Housing Roxbury SRO No Add Park Street – Codman Sq.- Supported Hsg. Dorchester Studio Yes Add Souris House – Supported Housing Dorchester SRO Yes Add Tuttle House – Supported Housing Dorchester SRO Yes Add Valentine Street – Supported Housing. This Roxbury SRO No Add Program is for women only. Walnut House – Supported Housing Roxbury SRO Yes Add Westminster House-Supported Housing Hyde Park SRO No Add II.