Economics of Adaptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Selection and Adaptation, Part I

Natural Selection and Adaptation, Part I 36-149 The Tree of Life Christopher R. Genovese Department of Statistics 132H Baker Hall x8-7836 http://www.stat.cmu.edu/~genovese/ . Plan • Review of Natural Selection • Detecting Natural Selection (discussion) • Examples of Observed Natural Selection ............................... Next Time: • Adaptive Traits • Methods for Reasoning about and studying adaptations • Explaining Complex Adaptations (discussion) 36-149 The Tree of Life Class #10 -1- Overview The theories of common descent and natural selection play different roles within the theory of evolution. Common Descent explains the unity of life. Natural Selection explains the diversity of life. An adaptation (or adaptive trait) is a feature of an organism that enhances reproductive success, relative to other possible variants, in a given environment. Adaptations become prevalent and are maintained in a population through natural selection. Indeed, natural selection is the only mechanism of evolutionary change that can satisfactorily explain adaptations. 36-149 The Tree of Life Class #10 -2- Darwin's Argument Darwin put forward two main arguments in support of natural selection: An analogical argument: Artificial selection A logical argument: The struggle for existence (As we will see later, we now have more than just argument in support of the theory.) 36-149 The Tree of Life Class #10 -3- The Analogical Argument: Artificial Selection 36-149 The Tree of Life Class #10 -4- The Analogical Argument: Artificial Selection 36-149 The Tree of Life Class #10 -5- The Analogical Argument: Artificial Selection Teosinte to Corn 36-149 The Tree of Life Class #10 -6- The Analogical Argument: Artificial Selection • Darwin was intimately familiar with the efforts of breeders in his day to produce novel varieties. -

9.1 Financial Cost Compared with Economic Cost 9.2 How

9.0 MEASUREMENT OF COSTS IN CONSERVATION 9.1 Financial Cost Compared with Economic Cost{l} Since financial analysis relates primarily to enterprises operating in the market place, the data of costs and retums are derived from the market prices ( current or expected) of the transactions as they are experienced. Thus the cost of land, capital, construction, etc. is the ~ recorded price of the accountant. By contrast, in economic analysis ( such as cost bene fit analysis) the costs and benefits of a project are analysed from the point of view of society and not from the point of view of a single agent's utility of the landowner or developer. They are termed economic. Some effects of the project, though conceming the single agent, do not affect society. Interest on borrowing, taxes, direct or indirect subsidies are transfers that do not deploy real resources and do not therefore constitute an economic cost. The costs and the retums are, in part at least, based on shadow prices, which reflect their "social value". Economic rate of retum could therefore differ from the financial costs which are based on the concept of "opportunity cost"; they are measured not in relation to the transaction itself but to the value of the resources which that financial cost could command, just as benefits are valued by the resource costs required to achieve them. This differentiation leads to the following significant rules in conside ring costs in cost benefit analysis, as for example: (a) Interest on money invested This is a transfer cost between borrower and lender so that the economyas a whole is no different as a result. -

1. Adaptation and the Evolution of Physiological Characters

Bennett, A. F. 1997. Adaptation and the evolution of physiological characters, pp. 3-16. In: Handbook of Physiology, Sect. 13: Comparative Physiology. W. H. Dantzler, ed. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. 1. Adaptation and the evolution of physiological characters Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, ALBERT F. BENNETT 1 Irvine, California among the biological sciences (for example, behavioral CHAPTER CONTENTS science [I241). The Many meanings of "Adaptationn In general, comparative physiologists have been Criticisms of Adaptive Interpretations much more successful in, and have devoted much more Alternatives to Adaptive Explanations energy to, pursuing the former rather than the latter Historical inheritance goal (37). Most of this Handbook is devoted to an Developmentai pattern and constraint Physical and biomechanical correlation examination of mechanism-how various physiologi- Phenotypic size correlation cal systems function in various animals. Such compara- Genetic correlations tive studies are usually interpreted within a specific Chance fixation evolutionary context, that of adaptation. That is, or- Studying the Evolution of Physiological Characters ganisms are asserted to be designed in the ways they Macroevolutionary studies Microevolutionary studies are and to function in the ways they do because of Incorporating an Evolutionary Perspective into Physiological Studies natural selection which results in evolutionary change. The principal textbooks in the field (for example, refs. 33, 52, 102, 115) make explicit reference in their titles to the importance of adaptation to comparative COMPARATIVE PHYSIOLOGISTS HAVE TWO GOALS. The physiology, as did the last comparative section of this first is to explain mechanism, the study of how organ- Handbook (32). Adaptive evolutionary explanations isms are built functionally, "how animals work" (113). -

Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Economics of Investment in Human Resources

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 04E d48 VT 012 352 AUTHOR Wood, W. D.; Campbell, H. F. TITLE Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Economics of Investment in Human Resources. An Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION Queen's Univ., Kingston (Ontario). Industrial Felaticns Centre. REPORT NO Eibliog-Ser-NO-E PU2 EATS 70 NOTE 217F, AVAILABLE FROM Industrial Relations Centre, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada ($10.00) EDBS PRICE EDPS Price MF-$1.00 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, *Cost Effectiveness, *Economic Research, *Human Resources, Investment, Literature Reviews, Resource Materials, Theories, Vocational Education ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography presents 389 citations of periodical articles, monographs, and books and represents a survey of the literature as related to the theory and application of cost-benefit analysis. Listings are arranged alphabetically in these eight sections: (1) Human Capital, (2) Theory and Application of Cost-Benefit Analysis, (3) Theoretical Problems in Measuring Benefits and Costs,(4) Investment Criteria and the Social Discount Rate, (5) Schooling,(6) Training, Retraining and Mobility, (7) Health, and (P) Poverty and Social Welfare. Individual entries include author, title, source information, "hea"ings" of the various sections of the document which provide a brief indication of content, and an annotation. This bibliography has been designed to serve as an analytical reference for both the academic scholar and the policy-maker in this area. (Author /JS) 00 oo °o COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS AND THE ECONOMICS OF INVESTMENT IN HUMAN RESOURCES An Annotated Bibliography by W. D. WOOD H. F. CAMPBELL INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS CENTRE QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY Bibliography Series No. 5 Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Economics of investment in Human Resources U.S. -

Lost Wages: the COVID-19 Cost of School Closures

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13641 Lost Wages: The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures George Psacharopoulos Victoria Collis Harry Anthony Patrinos Emiliana Vegas AUGUST 2020 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13641 Lost Wages: The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures George Psacharopoulos Harry Anthony Patrinos Georgetown University The World Bank and IZA Victoria Collis Emiliana Vegas The EdTech Hub Center for Universal Education, Brookings AUGUST 2020 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 13641 AUGUST 2020 ABSTRACT Lost Wages: The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures1 Social distancing requirements associated with COVID-19 have led to school closures. -

Evolutionary and Historical Biogeography of Animal Diversity Learning Objectives

Evolutionary and historical biogeography of animal diversity Learning objectives • The students can explain the common ancestor of animal kingdom. • The students can explain the historical biogeography of animal. • The students can explain the invasion of animal from aquatic to terrestrial habitat. • The students can explain the basic mechanism of speciation, allopatric and non-allopatric. The Common Ancestor of Animal Kingdom Characteristics of Animals • Animals or “metazoans” are typically heterotrophic, multicellular organisms with diploid, eukaryotic cells. • Trichoplax adhaerens is defined as an animal by the presence of different somatic (i.e., non-reproductive) cell types and by impermeable cell–cell connections. Trichoplax adhaerens Blackstone, 2009 Two Hypotheses for the Branching Order of Groups at the Root of the Metazoan Tree 1 2 The choanoflagellates serve as an outgroup in the Bilaterians are the sister group to the placozoan + analysis, and sponges are the sister group to the sponge + ctenophore + cnidarian clade, while placozoans placozoan + cnidarian + ctenophore + bilaterian are the sister group to the sponge + ctenophore + clade. cnidarian clade. Blackstone, 2009 Ancestry and evolution of animal–bacterial interactions • Choanoflagellates as the last common ancestor of animal kingdom. • Urmetazoan is the group of animal with multicellular and produce differentiated cell types (ex. Egg & sperm) R.A. Alegado & N. King, 2014 Conserved morphology and ultrastructure of Choanoflagellates and Sponge choanocytes The collar complex is conserved in choanoflagellates (A. S. rosetta) and sponge collar cells (B. Sycon coactum) flagellum (fL), microvilli (mv), a nucleus (nu), and a food vacuole (fv) Brunet & King, 2017 The Historical Biogeography of Animal Zoogeographic regions Old New Cox, 2001 Plate tectonic regulation of global marine animal diversity A. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

The Economic Cost of War May 2008

The Economic Cost of War May 2008 What is the true cost of war? As economists and government officials offer cost estimates of the current occupation of Iraq, others have begun to question the opportunity cost of forgone investment and develop - ment in American infrastructure and education. See “Debate rages about impact of Iraq war on U.S. econ omy” by Sue Kirchhoff in the April 10, 2008, USA Today . “I have a yardstick by which I test every major problem—and that yardstick is: Is it good for America?” —Dwight D. Eisenhower, 34th President of the United States The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the cost of U.S. operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and of other activities related to the war on terrorism, has totaled $651 billion from 2001 through the end of 2007. This estimate includes costs incurred through direct military operations and related expenses such as medical costs, disability compensation, and survivor benefits. However, the estimate does not include appropriations requested for 2008 and beyond. The CBO projects that the war on terrorism could require additional outlays of $570 billion to $1.2 trillion from 2008 to 2017. One difficulty with such projections is that a lot can change over the next 10 years, such as the course of the war. Another difficulty is that this estimate fails to fully consider the opportunity cost of funding the war on terrorism, which is the cost incurred by not investing that same money in other projects. A number of economists have attempted to quantify these explicit economic costs, such as forgone investments in American infrastructure, government research, or government assistance programs. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

Course Syllabus ECN101G

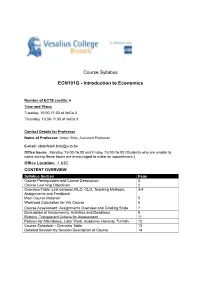

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates. -

Reducing Risks Through Adaptation Actions | Fourth National Climate

Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II 28 Reducing Risks Through Adaptation Actions Federal Coordinating Lead Authors Review Editor Jeffrey Arnold Mary Ann Lazarus U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cameron MacAllister Group Roger Pulwarty National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Chapter Lead Robert Lempert RAND Corporation Chapter Authors Kate Gordon Paulson Institute Katherine Greig Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center at University of Pennsylvania (formerly New York City Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency) Cat Hawkins Hoffman National Park Service Dale Sands Village of Deer Park, Illinois Caitlin Werrell The Center for Climate and Security Technical Contributors are listed at the end of the chapter. Recommended Citation for Chapter Lempert, R., J. Arnold, R. Pulwarty, K. Gordon, K. Greig, C. Hawkins Hoffman, D. Sands, and C. Werrell, 2018: Reducing Risks Through Adaptation Actions. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II [Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 1309–1345. doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH28 On the Web: https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/adaptation Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II 28 Reducing Risks Through Adaptation Actions Key Message 1 Seawall surrounding Kivalina, Alaska Adaptation Implementation Is Increasing Adaptation planning and implementation activities are occurring across the United States in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. Since the Third National Climate Assessment, implementation has increased but is not yet commonplace.