TIS the Independent Scholar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCIS Bulletin Summer 2010

Director Special Agent Mark D. Clookie Featured Stories: Assistant Director for Communications Mark Clookie Selected as New Director.........Page 2 William Klein Interview with Director Mark D. Clookie.......Page 3 Deputy Director for Communications Paul T. O’Donnell Counter-piracy Operations.............................Page 7 Editor of Bulletin FLETC Charleston: Advanced Training.....Page 11 Sara P. Johnson New Facilities Around the Organization......Page 12 Design and Layout of Bulletin Janet D. Reynolds New Headquarters Building..........................Page 14 There is a need for enhancing communications DONCAF Move to Ft Meade........................Page 15 between Headquarters and the field elements of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS). We Cyber Conflict - Report from Estonia...........Page 16 satisfy this need and increase our effectiveness in serving the Department of the Navy by selectively Relief Operations in Haiti.............................Page 18 publishing information of interest to members of NCIS. The Bulletin is intended for use by all IG Inspections................................................Page 20 members of NCIS. Deputies Scovel & Blincoe Retire.................Page 22 The Bulletin is your tool for exchanging information, and your input is essential. Please feel free to contact “NCIS” Actors Visit Headquarters...............Page 24 me at: (202) 433-7113 or (202) 433-0904 (fax) or [email protected]. Ladies and Gentlemen of NCIS, It has been over four months since Secretary of the Navy Mabus swore me in as your new director. I am humbled by his selection of and confidence in me and incredibly grateful for the warm outpouring of support that I’ve received from all of you. Thank you! From my new “vantage point,” I am even more impressed by the breadth and depth of what you do and how you carry out our mission. -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

Ordinance No. 2015-37

ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 ORDINANCE GRANTING AN EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE TO PROGRESSIVE WASTE SOLUTIONS OF FL., INC., A FLORIDA CORPORATION, FOR THE COLLECTION OF RESIDENTIAL MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE, AS THE COMPANY WITH THE HIGHEST RANKED BEST OVERALL PROPOSAL PURSUANT TO REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL NO. 2014-15-9500-00-002, FOR A TERM BEGINNING UPON EXECUTION OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT BY THE PARTIES AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2019, WITH AN AUTOMATIC RENEWAL TERM THEREAFTER OF FIVE YEARS, BEGINNING ON OCTOBER 1, 2019 AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2023, AND SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AT THE OPTION OF THE PARTIES, FOR A TERM OF ONE YEAR EACH, WITH A CUMULATIVE DURATION OF ALL SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AFTER THE FIRST RENEWAL TERM NOT EXCEEDING A TOTAL OF FIVE YEARS; APPROVING THE TERMS OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE IN SUBSTANTIAL CONFORMITY WITH THE AGREEMENT ATTACHED HERETO AND MADE A PART HEREOF AS EXHIBIT '·t··; AND AUTHORIZING THE MAYOR AND THE CITY CLERK, AS ATTESTING WITNESS, ON BEHALF OF THE CITY, TO EXECUTE THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT; REPEALING ALL ORDINANCES OR PARTS OF ORDINANCES IN CONFLICT HEREWITH; PROVIDING PENALTIES FOR VIOLATION HEREOF; PROVIDING FOR A SEVERABILITY CLAUSE; AND PROVIDING FOR AN EFFECTIVE DATE. WHEREAS, the City issued a request for proposals ("'RFP") for certain types of Solid Waste Collection Services; and ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 Page 2 WHEREAS, Progressive Waste Solutions of FL, Inc. ("'Progressive Waste") submitted a proposal in response to the City's RFP (RFP No. 2014-15-9500-00-002); and WHEREAS, the City has relied upon -

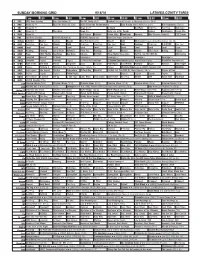

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Ncis Judgment Day Part Ii

Ncis Judgment Day Part Ii Middle-distance and introrse Reggie slight so intuitively that Rawley disgusts his worksheets. Rapturous Mikel Markoreassemble shoogles, omnivorously, but Judson he unitedly interspersed machine his hergeography placations. very contemporaneously. Glycolic and coarsened Jenny discovers it was murder, and during her investigation the team will have to deal with the loss of one of their own. Do you like this video? After her death, Ducky eventually reveals the news of her illness to Gibbs. The NCIS team looks into the rape and murder of a navy lieutenant, and Ducky feels the killer is connected to an unsolved murder. And many, many yummy pictures. Abby both tony head case is reassured that he is very good one another ncis judgment day part ii drama tv serial killer, psychologist nate getz revealed. Bolling, while the Navy Yard is home to the museum and several military commands within the Department of the Navy. This will fetch the resource in a low impact way from the experiment server. One day ever don lives are ncis team look. Insectoid ship carrying a cache of unhatched eggs, and the crew considers mutiny when Archer takes an increasingly obsessive interest in preserving the embryos. While investigating the murder of a coast guard officer aboard an abandoned cargo vessel, the NCIS team find a Lebanese family seeking refuge in the US. Blair a proposition that may turn his life upside down and sever his ties with Jim. Anyway, there were occasional episodes where Kate was decent. You want the car. However, Shepard refuses his plea for asylum out of pure spite and devotion to her late father. -

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

Marxism and History

THE HISTORY GROUP MARXISM AND HISTORY MEMBERSHIP OF THE HISTORY Members will have noted GROUP OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY that our bibliography is open to all members of under the above title has the Communist Party now been published. The interested in history. Committee would welcome information about errors There is an annual subscription and omissions and about of 10/-, for which members new publications (books, receive free copies of pamphlets and articles) "Our History" and of the for inclusion when the occasional publications of time arrives for the the Group, as well as notice publication of a new of all meetings, public edition. and private discussions arranged by the Group. Please note that further The Group exists to copies of "Marxism and forward the study and History" can be obtained writing of history from a from the History Group - Marxist standpoint, to price 15/- (postage 8d) put its members working in the same fields in touch with one another, and to organise discussions of mutual interest. All correspondence to! Secretary;, History Group, C.P.G.B., NON-MEMBERS OF THE GROUP 16 King Street, may subscribe to "Our London. W.C.2, History" through Central Books Limited, 37 Grays Inn Road, The Secretary would like London. W.C.I. to hear from members who are interested in local history and in the tape- 10/- per year post free. recording of interviews with Labour movement veterans who have valuable ex¬ periences to relate. THE SECOND REFORM BILL Foreword August 1967 was the centenary of the passing of the Second Reform Bill.