Spatial Diagnosis and Media Treatments By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choamskx Races Hessen

iI Ii - ~~~~~~~~---I I -Continuous News Serice The Weather. I I Since 1881." Clear and warmer; high in the 70's I iI i VOLUME 89, No. 35' - MITCAMBRIDGE,MASSAC:HUSETTS FRIDAY, OCTOBER 10, 1969 FIVE CENTS -- _ _- ,- - _ . .. Faculty meeting convenes i GA i to consider Oct. 15 action voces panel support - ~ ~~~~~~~-: A special faculty meeting wil C.'L. Miller, Head of the Depa#!- convene today-to consider a'-re- ment- of Civil Engineering; I. solution calling for "a convoca- 'Ross, -Headcof the Department tion of the MIT community 'at of -Chemistry;, A.H. Shapiro, 1:30 pm Wednesday, October Read of the Departinent of Me- IS." chanical Engineering; L.D. As evidence of widespread Smullin- Head of the Depast- community support for the ment of Electrical Engineering; Moratorium, the resolution cites and V.F. Wwisskopf, Head of the petition circulated' among the Department of Physics. the faculty, the vote of the Ge- neral Assembly, and the state- A similar meeting of the Har- ment approved by the Corpora- vard faculty took place Tuesday. tion. After much discussion, an amended moratorium resolution A second resolution, to be in- was- passed which states that the troduced by SA-CC, calls- for -faculty "recognizes that October completely dlosing the Institute. 15th is a day of protest against Until now, tliere has been no 'the war and, while not commit- official recognition of the Mora- ting any individual member,- torium by the, Institute. How- re-affirms its members' right to,- ever, - many -faculty members suspend classes on that day." have already canceled or resche- duled their October 15 classes. -

Self-Guided Walking Tour of the MIT Campus

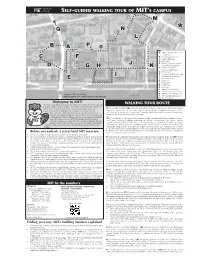

Self-Guided Walking Tour of the MIT Campus P AInformation Center MIT Museum → B Stratton Student Center → N52 C Kresge Auditorium ➔ DMIT Chapel → E Hart Nautical Galleries TECHNOLOGY Building 5 ➔ SQUARE M F Bldg. 3/Design and A Manufacturing Display S S A C GKillian Court H U HHayden Memorial S E Library Building T T S I McDermott Court A V E JTech Coop N M ➔ A U IN KAn Athena Computer E ➔→ S ➔→→ TR Cluster →→ E →→→ ET → ➔→ O L Edgerton’s Strobe T → 32 STREE Stata ➔ R VASSA Alley ➔ Center MBarker Engineering TREET AR S ➔ T SS → Library - Bldg. 10-500 VA E J E E19 Tech Coop → → R NCompton Gallery 57 T → → S T T Bldg. 10-1st floor 68 S ➔ → E Kendall M E18 T O Stata Center → A Square W35 13 ➔ ➔ B ➔ 56 E17 E25 E38 P MIT Museum ➔ Zesiger ➔ 16 → K 66 W20 ➔→→→→ ➔ → → N → Whitaker College ➔→→ Center ➔→ → ➔→→ ➔ ➔ → ➔ ➔ You are here 10 8 → ➔ → 7➔→ M 4 A → E23 Information 54 C Center L 18 → E15 MIT Medical F → D ➔ W16 I 62 64 → ➔→→W15➔ 3 4 6 McDermott E ➔ E14 Court → → 5 → E40 G ➔ ➔→→→ ➔ ➔→→→→→→ ➔→→→→→→→→→→→→→→14N ➔ 14W 14E E2 E53 1 Killian Court 2 E51 H 14S 50 E52 Gray E56 House Sloan School D O R M I T O R I E S MEMORIAL DRIVE MEMORIAL DRIVE Welcome to MIT! held at 10:00 am and names. The numbering you see a number on the route, letters of the alpha- William Barton Rogers, a problems. Today education The following suggested 2:00 pm. system might appear office doors, the first bet are used to avoid distinguished natural and research, with tour route and description confusing at first, but there number refers to the confusion with the building scientist, founded MIT to relevance to the practical should aid you in exploring We suggest that you begin is a logical explanation as building number and then numbers. -

O Nien Un Es a Is E Two New Honors Given at Yearly Awards Convocation

I I I . I ve -o nien Two new honors given at I un es a is e By Bon Frashure of the secrty after allowance Trhe yearly Awards Convocation pWThas names of the representatives estabished an Inde- for improvements. of the remang fraterriti'es were SexetResidence Development By Steve Portny field '64 for his "spirit, dedica- 3. The maxdmum. loan term antnounced last Mkght at a work- nhwhich may assist tindepen- The annual Awards Conlvocaton tion, and service" to Mffr. The will be 40 years. in meeting to implement the seon ivingid grops in improig. IRD Fund. was held last Saturday in Kresge new award came from a adexpaig 4. The minimum. rate of in- proposal by the Activities Devel- their housing fat Marshall. B. Dalton '15, Chair- Auditorium. Featured was the 0 oite administrtiors officers terest vEll be three percot. presentation of the Kar Taylor opment Board. Namned in honor 5. Gifts to the IRD Fund must man of the Board of the Boston of William L. Steward Jr. '26, anounced Jast FridaY. Manufacturers Mutual Insurance Compton Awards given in reco- Fund provisins provide that the prncpal wil niition of 'outanftng contribul- the award is ~given to students not be expended, and givers must Company and -a Life Member of who have participated The IRD Flund will be an en- the MITX Corporatimn, will chair tions in promoing high standards actively in dwnnt, thie income of which permit use of the income of the of achievement and good citizen- school activities. fund for any corporate purpose both the Alumni IFC! and the Saye be used by the Corporation central ship mithinn the MIT community." Recipents of the award are: of MIT. -

PDF: V110-N42.Pdf

-- 1LI · -L I s -- I · I Il Walker groups worried Administrators call student fears nonsense By Brian Rosenberg to Bradley, who entered MIT as a in and out of student-assigned Changes to several rooms in member of the Class of 1976. space." Walker Memorial have caused "People were disturbed by things Report recommended many student groups to fear that they were seeing [in Walker]," he they will lose their spaces. They said. converting Walker are worried about hostility from The committee has members The Walker committee believes the Campus Activities Complex from several organizations, but the changes in Walker are part of and expansion by the School of most will not admit their mem- a plan by the School of Human- Humanities and Social Science. bership out of "fear of reprisals ities, particularly the Program in The groups, particularly the from the CAC," said Bradley, Theater Arts and Dance, to humor magazine Voo Doo and who acts as a spokesman for the assume control of the building. the Special Effects Club, began group. He added that "Voo Doo Committee members cite a to worry after a'third floor dark- is willing to be open [about their 1988 report, "Accommodating room was padlocked last Novem- membership] because we have the Performing Arts at MIT," as ber. The installation of a lock on nothing to lose" from conflict the basis for their suspicions. The the third floor showers and the with the CAC. report outlines four alternatives renovation of room 201 also Phillip J. Walsh, director of for giving the performing arts Kristine AuYeung/The Tech caused concern, according to Bri- the CAC, said that groups in more space. -

MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2Nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected]

2014–2015 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Dani DeSteven About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily contents Photograph by Christopher Brown navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Discover more articles, tips and local business information by visiting the online guide at: www.universityparent.com/mit MIT Guide The presence of university/college logos and marks in this guide does not mean the school | Comprehensive advice and information for student success endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 6 | Welcome to MIT 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 8 | MIT Parents Association Boulder, CO 80301 www.universityparent.com 10 | MIT Parent Giving Top Five Reasons to Join Advertising Inquiries: 11 | (855) 947-4296 12 | 100 Things to Do before Your Student Graduates MIT [email protected] 20 | Academics Top cover photo by Christopher Harting. 21 | Resources for Academic Success 22 | Supporting Your Student 24 | Campus Map 27 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 28 | MIT Police and Campus Safety SARAH SCHUPP PUBLISHER 30 | Housing MARK HAGER DESIGN MIT Dining 32 | MICHAEL FAHLER AD DESIGN 33 | Health Care What to Do On Campus Connect: 36 | 39 | Navigating MIT facebook.com/UniversityParent 41 | Academic Calendar MIT Songs twitter.com/4collegeparents 43 | 45 | Contact Information © 2014 UniversityParent Photo by Tom Gearty 48 | MIT Area Resources 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 5 www.universityparent.com/mit 5 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

February 8, 2006 Techtalk S ERVING T HE M I T C OMMUNITY

Volume 50 – Number 16 Wednesday – February 8, 2006 TechTalk S ERVING T HE M I T C OMMUNITY Researchers fired up over new battery New sensor Deborah Halber and associate director of the Laboratory for Electro- News Office Correspondent magnetic and Electronic Systems; John G. Kassakian, EECS professor and director of LEES; and Ph.D. can- makes splash didate Riccardo Signorelli are using nanotube struc- Just about everything that runs on batteries — tures to improve on an energy storage device called flashlights, cell phones, electric cars, missile-guidance an ultracapacitor. systems — would be improved with a better energy Capacitors store energy as an electrical field, counting fish supply. But traditional batteries haven’t progressed making them more efficient than standard batter- far beyond the basic design developed by Alessandro ies, which get their energy from chemical reactions. Anne Trafton Volta in the 19th century. Ultracapacitors are capacitor-based storage cells that News Office Until now. provide quick, massive bursts of instant energy. They Work at MIT’s Laboratory for Electromagnetic and are sometimes used in fuel-cell vehicles to provide an Electronic Systems (LEES) holds out the promise of extra burst for accelerating into traffic and climbing the first technologically significant and economically hills. Researchers at MIT have found a new way of look- viable alternative to conventional batteries in more However, ultracapacitors need to be much larger ing beneath the ocean surface that could help definitively than 200 -

MIT Cheers New Nobelist Chemistry Set Prof

Volume 50 – Number 5 Wednesday – October 19, 2005 TechTalk S ERVING T HE M I T C OMMUNITY MIT cheers new Nobelist Chemistry set Prof. Richard really pays off Schrock wins Elizabeth A. Thomson News Office 2005 prize Richard Schrock was 8 when his broth- Elizabeth A. Thomson er gave him his first chemistry set, a gift News Office that piqued a passion that would ultimately lead to Schrock’s sharing the 2005 Nobel Prize in chemistry. MIT Professor Richard R. Schrock has At a wide-ranging MIT press confer- won the 2005 Nobel Prize in chemistry for ence on Oct. 5, the new laureate described the development of a chemical reaction why chemistry is so compelling for him, now used daily in the chemical industry what it was like to get “the call” at 5:30 in for the efficient and more environmentally the morning, and much more. friendly production of important pharma- “I was shaking so hard I could hardly ceuticals, fuels, synthetic fibers and many hold the phone,” said the Frederick G. other products. Keyes Professor of Chemistry, describing Schrock, the Frederick G. Keyes Pro- his conversation with representatives of fessor of Chemistry at MIT, shares the the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. prize with Yves Chauvin of the Institut Later he called his soon-to-be 92-year- Français du Pétrole and Robert H. Grubbs old mother. “I told her I’d won a Nobel of Caltech “for the development of the Prize, and she said, ‘A what?’ She’s a little metathesis method in organic synthesis.” hard of hearing.” Once she understood, Metathesis was discovered in the however, “she was very excited, and happy 1950s by industry researchers, but was to hear that she’ll visit Stockholm for the not understood until 1971. -

A B C D E F G H I J K L M 0 P

SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF M.....IT’S CAMPUS ... M j .... Q N ....... * L ........ ........... B .....A P.. 0 ... .... Lobby 7 & Visitor Info Center ....... A ..... (77 Mass Ave) C F B Stratton Student Center C Kresge Auditorium .... MIT Chapel D E Building 1 (nearby entrance J to Hart Nautical Gallery) D........ ......... G ..... H K F Building 3/Design & ..... .... Manufacturing display ......... .............................. G Killian Court H Ellen Swallow Richards Lobby I I Hayden Memorial Library E J McDermott Court K Media Lab L North Court ......... M Koch Institute N Stata Center O Edgerton’s Strobe Alley P Memorial Lobby / Barker Library Q 1 smoot = 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) Q MIT Museum (265 Mass Ave) Bridge length = 364.4 smoots, plus or minus one ear MIT Coop/Kendall Square Q* Smoot markings Welcome to MIT! forma- We hope you enjoy your visit! The tour route outlined on this map will WALKING TOUR ROUTEn help you explore MIT’s campus. The Office of Admissions conducts information sessions followed by student-led campus tours for u Leave Lobby 7 (Bldg. 7 [A]) and cross Massachusetts Avenue (Mass Ave). Central and Harvard prospective students and families, Mon–Fri, excluding federal, Squares are up the street to your right, and the Harvard Bridge (leading into Boston) is to your Massachusetts, and Institute holidays and the winter break left. Mass Ave is a main street connecting Cambridge and Boston, and bus stops servicing major period. Info sessions begin at 10 am and 2 pm; campus tours routes can be found on either side of the street. -

Town Gown Report MIT MIT.NANO FACILITY / 6901-00 to the City of Cambridge

Town Gown Report MIT MIT.NANO FACILITY / 6901-00 to the City of Cambridge EXTERIOR ART VIEW TO EAST 11.18.14 2014 Town Gown Report to the City of Cambridge 2013-2014 Term (7/1/13 - 6/30/14) Submitted December 15, 2014 I. Existing Conditions 1 A. Faculty & Staff 1 B. Student Body 2 C. Student Residences 3 D. Facilities & Land Owned 4 E. Real Estate Leased 6 F. Payments to City of Cambridge 6 G. Institutional Shuttle Information 7 II. Future Plans Narrative 8 A. Moving Ideas into Action 8 B. Capital Planning, Renewal and Comprehensive Stewardship 12 C. MIT Students, Faculty, and Staff 12 D. Housing 13 E. Looking Ahead at MIT Planning & Development 15 F. Transportation 18 G. Sustainability 19 III. List of Projects 21 A. Completed in Reporting Period 21 B. In Construction 21 C. In Planning & Design 23 IV. Mapping Requirements 24 Map 1: MIT Property in Cambridge 25 Map 1a: MIT Buildings by Use 26 Map 2: MIT Projects 27 Map 3: Future Development Opportunities 28 Map 4: MIT Shuttle Routes 29 Map 5: MIT LEED Certified Buildings 30 Map 6: MIT Energy Efficiency Upgrade Projects 31 V. Transportation Demand Management 32 A. Commuting Mode of Choice 32 B. Point of Origin for Commuter Trips to Cambridge 32 C. TDM Strategy Updates 33 VI. Institution Specific Information Requests 34 Town Gown Report to the City of Cambridge 2013-2014 Term (7/1/13 - 6/30/14) Submitted December 15, 2014 I. Existing Conditions A. Faculty & Staff 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2024 (projected) Cambridge-based Staff 9,000- Head Count 8,857 8,893 9,124 9,329 9,692 10,000 FTEs 7,461 7,483 7,707 7,954 8,294 Post-Doctoral Staff 1 1,402 1,421 Cambridge-based Faculty Head Count 1,012 1,002 1,003 1,007 1,012 ~1,100 FTEs 1,009 997 997 1,002 1,005 Number of Cambridge Residents Employed at Cambridge 2,170 2,258 2,359 2,305 2,347 ~2,400 Facilities 1 1 Post-Doctorals are classified as staff and included in the headcount for Cambridge-based Staff. -

Pedestrian Committee 2018 MIT Public Art Walk Brochure

WINDSOR ST MIT Public Art Walking Tour S T A T E M S 0 A T S S A Cambridge, Massachusetts C A H L U B S A E N T Y OSBORN ST June 2018 T S S T A V E 1/16 Miles A M M A H 5 I N E PORTLAND ST 1/8 R S V S T 6 A T S S S T A R S T ¯ M E M O R IA L D R 4 8 Map prepared on June 6, 2018. CDD GIS C:\Projects\Env_Trans\PedestrianCommittee\PedestrianWalkingTour2018.mxd 10 9 G ALILEI WAY 3 7 M C A I h N a S rl T e s R 2 i 1 v Walking Itinerary 1. Transparent Horizon, Louise Nevelson (1975) 2. La Grande Voile,Alexander Calder (1965) 3. Chord, Antony Gormley (2015) 4. Bars of Color within Squares (MIT), Sol LeWitt (2007) 5. Alchemist, Jaume Plensa (2010) e 6. MIT Chapel, Eero Saarinen (1954) 7. Aesop’s Fables, II, Mark Di Suvero (2005) 8. Ray and Maria Stata Center, Frank Gehry (2004) 9. Non-Object (Plane),Anish Kapoor (2010) 10 r AMES ST .S ean Collier Memorial, J. Meejin Yoon (2015) M E M ! O R IA L List VisualArts Center, D DOCK ST R D E 20 Ames Street A KENDALL/MIT C Begin at O N S A T ! M ! T H E CARLETON ST B R R S O T A S D T W A Y HAYWARD ST 1. Louise Nevelson’s “Transparent Horizon” (1975) 6. -

A GUIDE for PARENTS Produced By

2015 –2016 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Christoper Harting About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in contents Photograph by Christoper Brown partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Top cover photograph by Christoper Harting. MIT Guide Bottom cover photo by Tom Gearty. | Comprehensive advice and information for student success Discover more articles, tips, and local business information by visiting the online guide at: 4 | Welcome to MIT www.universityparent.com/mit 6 | Mission and Origins The presence of university/college logos and 7 | Traditions and Hacks marks in this guide does not mean the school 11 | Navigating MIT endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 13 | What to Do on Campus 16 | Academics 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 Boulder, CO 80301 19 | 2014–2015 Enrollment www.universityparent.com 22 | Faculty and Staff Advertising Inquiries: 24 | Students after Graduation (866) 721-1357 Learning Communities [email protected] 26 | 28 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 29 | Housing 31 | MIT Dining 32 | Health Care SARah Schupp PUBLISHER 34 | MIT Police and Campus Safety maRK hagER DESIGN 35 | MIT Parents Association 38 | Campus Map Connect: 40 | Boston Transit Map facebook.com/UniversityParent 42 | Subway Map 44 | Academic Calendar twitter.com/4collegeparents 46 | Contact Information Photograph by Nick Schietromo © 2015 UniversityParent 48 | MIT Area Resources 2 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 3 www.universityparent.com/mit 3 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

Campus Walking Tour

(O) MIT Museum O 265 Massachusetts Avenue NE25 M a 36 M L s 51 s a c h 39 38 76 u 32 MIT Chapel (Building W15). You are welcome to enter the non-denominational Chapel unless it is MIT Media Lab (Building E14) and List Visual Arts Center (Building E15). The Media Lab s e t t 37 s being used for a service or function. The Chapel was designed by renowned architect Eero Saarinen in contains more than 25 research groups working on 350+ projects that range from neuroengineering to A 35 v Campus e NE20 ssar Str W33 Va eet n 1955. Inside, a metal altarpiece created by legendary sculptor Harry Bertoia is used to scatter light that how children learn to developing the city car of the future. The first floor is open to visitors. u e enters the space from the beautiful domed skylight. 33 24 E19 The List Visual Arts Center, MIT’s contemporary art museum, collects, commissions, and presents 31 M W31 ain Fun Fact: The Chapel features a 1,300-pound bell cast at MIT’s Merton C. Flemings Metals provocative, artist-centric projects that engage MIT and the global arts community. The List is free and 17 26 K Stre Walking Tour W32 68 et Processing Laboratory. open to the public. For more information visit listart.mit.edu. B E18 W35 9 12 North Court 13 N E17 Fun Fact: The List has a Campus Loan Art Program and makes artwork from their permanent Welcome to MIT! 54 E25 Kendall/MIT W20 66 Red Line Hart Nautical Gallery of the MIT Museum (Building 1, through the doorway at 33 Mass.