Remuneration of Authors of Books and Scientific Journals, Translators, Journalists and Visual Artists for the Use of Their Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOOK Master Level 2 Msc in Corporate Finance & Banking FINANCIAL ECONOMICS ACADEMIC YEAR 2016-2017

BOOK Master Level 2 MSc in Corporate Finance & Banking FINANCIAL ECONOMICS ACADEMIC YEAR 2016-2017 FE Track MASTER 2 FINANCIAL ECONOMICS - MSc in CORPORATE FINANCE & BANKING ECTS for ECTS for Hours per INCOMING ECTS for CAMPUS PROGRAMME SEM. STATUS N° COURSE NAME MiM MSc Student DD INCOMING Student Student NICE ED MScCORP S1 SEM 4374 Take ownership of your academic environment 2 --- NICE ED MScCORP S1 SEM 4375 Preparing yourself for learning with cases 4 - - - NICE ED MScCORP S1 SEM 2742 Intercultural Seminar 9 - - - - NICE ED MScCORP S1 SEM 3659 Research Seminar (for Student Research Team ONLY) 30 - - NICE ED MScCORP S1 SEM 764 Financial Modeling with Excel 15 1,5 1,5 1,5 1,5 NICE ED MScCORP S1 SEM 884 Fundamentals of Corporate Law 15 1,5 1,5 1,5 1,5 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 3476 Principles of business Taxation 18 2 2 2 2 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 3477 Advanced Financial & Credit Analysis 30 4 4 4 4 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 1108 Advanced Strategies 21 4 4 4 4 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 2753 Advanced Corporate Finance 30 4 4 4 4 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 3867 Banking & Bankruptcy 18 2 2 2 2 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 2754 Corporate Treasury Management 18 2 2 2 2 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 1111 Real options 15 2 2 2 2 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 173 Values, Cooperation and Trust (only for incoming) 30 7 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 1351 French course (for visiting students only) 30 0 5 NICE ED MScCORP S1 MP 1013 Master Project 50 5 5 5 NICE ED MScCORP S1 CC 1011 TI&CD 20 2 2 2 250 30 30 30 35 SEMESTER 2 - Major in Financial Management 235 30 45 30 35 NICE ED MScCORP S2 SEM 3667 -

Susanna Lea Associates PARIS - NEW YORK - LONDON Spring 2020 PARIS 28 Rue Bonaparte 34 LANGUAGES 49 LANGUAGES 30 LANGUAGES

Susanna Lea Associates PARIS - NEW YORK - LONDON Spring 2020 PARIS 28 rue Bonaparte 34 LANGUAGES 49 LANGUAGES 30 LANGUAGES 75006 Paris MECH DESIGNER: KD 5.0938 × 7.25 SPINE: 0.625 FLAPS: 0 5C (PMS 185C) + UNCOATED tel: +33 (0)1 53 10 28 40 Marie Robert r modern dilemmas f Versilio Advice fo rom the Marie t Western Philos reates ophers @versilio G Robert How can Kant comfort you when you get ditched via text message? Can Aristotle cure your hangover? What can Heidegger say to make you feel better when your dog dies? When You Kant Figure It Out, Ask a Philosopher offers pearls of en wisdom from the greatest Western philosophers to help us face and make h light of some of the daily challenges of modern life. Inside, you’ll find… When You Kant figure it out ... NEW YORK advice from Epicurus on disconnecting Wu from constant news alerts and social media updates yo ant Nietzsche’s take on getting in shape K 331 West 20th Street John Stuart Mill’s tips for handling bad birthday presents g wisdom from Levinas on parenting teenagers fi ure and Wittgenstein’s strategies for dealing with horrible in-laws New York, NY 10011 Hilarious, practical, and edifying, When You Kant Figure It Out, Ask a Philosopher enlists the best thinkers of the past so we can all make ut... sense of a chaotic new world. it o tel: +1 (646) 638 1435 holds degrees in French and Mariephilosophy. SheRobert is a teacher, a Montessori school founder, and the current academic program coordinator for Paris’s Lycée International Montessori. -

HBG and Amazon Joint Release 11 13 14-1

HACHETTE BOOK GROUP AND AMAZON REACH NEW EBOOK AND PRINT BOOK AGREEMENT November 13, 2014 - Hachette Book Group and Amazon (AMZN) today announced that the companies have reached a new, multi-year agreement for ebook and print sales in the US. Michael Pietsch, Hachette Book Group CEO said, "This is great news for writers. The new agreement will benefit Hachette authors for years to come. It gives Hachette enormous marketing capability with one of our most important bookselling partners.” "We are pleased with this new agreement as it includes specific financial incentives for Hachette to deliver lower prices, which we believe will be a great win for readers and authors alike," said David Naggar, Vice President, Kindle. The new ebook terms will take effect early in 2015. Hachette will have responsibility for setting consumer prices of its ebooks, and will also benefit from better terms when it delivers lower prices for readers. Amazon and Hachette will immediately resume normal trading, and Hachette books will be prominently featured in promotions. About Hachette Book Group: Hachette Book Group is a leading trade publisher based in New York and a division of Hachette Livre, the third-largest trade and educational publisher in the world. HBG publishes under the divisions of Little, Brown and Company, Little Brown Books for Young Readers, Grand Central Publishing, Orbit, Hachette Books, Hachette Nashville, and Hachette Audio. About Amazon: Amazon.com opened on the World Wide Web in July 1995. The company is guided by four principles: customer obsession rather than competitor focus, passion for invention, commitment to operational excellence, and long-term thinking. -

Hachette Book Group V. Internet Archive

Case 1:20-cv-04160 Document 1 Filed 06/01/20 Page 1 of 53 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x HACHETTE BOOK GROUP, INC., : HARPERCOLLINS PUBLISHERS LLC, JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC., and PENGUIN RANDOM : 20 Civ. _____________ HOUSE LLC, : ECF Case Plaintiffs, : : COMPLAINT -against- : TRIAL BY JURY DEMANDED : INTERNET ARCHIVE and DOES 1 through 5, : inclusive, : Defendants. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x Plaintiffs Hachette Book Group, Inc. (“Hachette”), HarperCollins Publishers LLC (“HarperCollins”), John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (“Wiley”), and Penguin Random House LLC (“Penguin Random House”), by and through their attorneys Davis Wright Tremaine LLP and Oppenheim + Zebrak, LLP, for their Complaint, hereby allege against Defendant Internet Archive (“IA” or “Defendant”) and Does 1 through 5 as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiffs Hachette, HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, and Wiley (collectively, “Plaintiffs” or “Publishers”) bring this copyright infringement action against IA in connection with website operations it markets to the public as “Open Library” and/or “National Emergency Library.” Plaintiffs are four of the world’s preeminent publishing houses. Collectively, they publish some of the most successful and leading authors in the world, investing in a wide range of fiction and nonfiction books for the benefit of readers everywhere. All of the Plaintiffs are member companies of the Association of American Publishers, the mission of which is to be the voice of American publishing on matters of law and public policy. 1 Case 1:20-cv-04160 Document 1 Filed 06/01/20 Page 2 of 53 2. Defendant IA is engaged in willful mass copyright infringement. Without any license or any payment to authors or publishers, IA scans print books, uploads these illegally scanned books to its servers, and distributes verbatim digital copies of the books in whole via public-facing websites. -

Democratizing E-Book Retailing

3,000 plus Join us and more than 3,000 publishers in Democratizing E-Book Retailing 10 Finger Press Acrobat Books Alan Phillips 121 Publications Action Publishing LLC Alazar Press 1500 Books Active Interest Media, Inc. Alban Books 3 Finger Prints Active Parenting Albion Press 3G Publishing, Inc. Adair Digital Alchimia 498 Productions, LLC Adaptive Studios Alden-Swain Press 4th & Goal Publishing Addicus Books Aleph Book Company Pvt.Ltd 5Points Publishing Adlai E. Stevenson III Algonquin Books 5x5 Publications Adm Books Ali Warren 72nd St Books Adriel C. Gray Alight/Swing Street Publishing A & A Johnston Press Advanced Perceptions Inc. Alinari 24 Ore A & A Publishers Inc Advanced Publishing LLC All Clear Publishing A C Hubbard Advantage Books All In One Books - Gregory Du- A Sense Of Nature Adventure Street Press LLC pree A&C Publishing Adventures Unlimited Press Allen & Unwin A.R.E. Press Aepisaurus Publishing, LLC Allen Press Inc AA Publishing Aesop Press ALM Media, LLC Aadarsh Pvt Ltd Affirm Press Alma Books AAPC Publishing AFG Weavings LLC Alma Rose Publishing AAPPL Aflame Books Almaden Books Aark House Publishing AFN Alpha International Aaron Blake Publishers African American Images Altruist Publishing Abdelhamid African Books Collective AMACOM Abingdon Press Afterwords Press Amanda Ballway Abny Media Group AGA Institute Press AMERICA SERIES Aboriginal Studies Press Aggor Publishers LLC American Academy of Abrams AH Comics, Inc. Oral Medicine Absolute Press Ajour Publishing House American Academy of Pediatrics Abstract Sounds Books, Ltd. AJR Publishing American Automobile Association Academic Foundation AKA Publishing Pty Ltd (AAA) Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics Akmaeon Publishing, LLC American Bar Association Acapella Publishing Aladdin American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Spring 2021 Nonfiction Rights Guide

Spring 2021 Nonfiction Rights Guide 19 West 21st St. Suite 501, New York, NY 10010 / Telephone: (212) 765-6900 / E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS SCIENCE, BUSINESS & CURRENT AFFAIRS HOUSE OF STICKS THE BIG HURT BRAIN INFLAMMED HORSE GIRLS FIRST STEPS YOU HAD ME AT PET NAT RUNNER’S HIGH MY BODY TALENT MUHAMMAD, THE WORLD-CHANGER WINNING THE RIGHT GAME VIVIAN MAIER DEVELOPED SUPERSIGHT THE SUM OF TRIFLES THE KINGDOM OF CHARACTERS AUGUST WILSON WHO IS BLACK, AND WHY? CRYING IN THE BATHROOM PROJECT TOTAL RECALL I REGRET I AM ABLE TO ATTEND BLACK SKINHEAD REBEL TO AMERICA CHANGING GENDER KIKI MAN RAY EVER GREEN MURDER BOOK RADICAL RADIANCE DOT DOT DOT FREEDOM IS NOT ENOUGH HOW TO SAY BABYLON THE RISE OF THE MAMMALS THE RECKONING RECOVERY GUCCI TO GOATS TINDERBOX RHAPSODY AMERICAN RESISTANCE SWOLE APOCALYPSE ONBOARDING WEATHERING CONQUERING ALEXANDER VIRAL JUSTICE UNTITLED TOM SELLECK MEMOIR UNTITLED ON AI THE GLASS OF FASHION IT’S ALL TALK CHANGE BEGINS WITH A QUESTION UNTITLED ON CLASSICAL MUSIC MEMOIRS & BIOGRAPHIES STORIES I MIGHT REGRET TELLING YOU FIERCE POISE THE WIVES BEAUTIFUL THINGS PLEASE DON’T KILL MY BLACK SON PLEASE THE SPARE ROOM TANAQUIL NOTHING PERSONAL THE ROARING GIRL PROOF OF LIFE CITIZEN KIM BRAT DON’T THINK, DEAR TABLE OF CONTENTS, CONT. MINDFULNESS & SELF-HELP KILLING THATCHER EDITING MY EVERYTHING WE DON’T EVEN KNOW YOU ANYMORE SOUL THERAPY THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OF GROWING YOUNG HISTORY TRUE AGE THE SECRETS OF SILENCE WILD MINDS THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE INTELLIGENT LOVE THE POWER OF THE DOWNSTATE -

Title of Book/Magazine/Newspaper Author/Issue Datepublisher Information Her Info

TiTle of Book/Magazine/newspaper auThor/issue DaTepuBlisher inforMaTion her info. faciliT Decision DaTe censoreD appealeD uphelD/DenieD appeal DaTe fY # American Curves Winter 2012 magazine LCF censored September 27, 2012 Rifts Game Master Guide Kevin Siembieda book LCF censored June 16, 2014 …and the Truth Shall Set You Free David Icke David Icke book LCF censored October 5, 2018 10 magazine angel's pleasure fluid issue magazine TCF censored May 15, 2017 100 No-Equipment Workout Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 of the Most Beautiful Women in Painting Ed Rebo book HCF censored February 18, 2011 100 Things You Will Never Find Daniel Smith Quercus book LCF censored October 19, 2018 100 Things You're Not Supposed To Know Russ Kick Hampton Roads book HCF censored June 15, 2018 100 Ways to Win a Ten-Spot Comics Buyers Guide book HCF censored May 30, 2014 1000 Tattoos Carlton Book book EDCF censored March 18, 2015 yes yes 4/7/2015 FY 15-106 1000 Tattoos Ed Henk Schiffmacher book LCF censored December 3, 2007 101 Contradictions in the Bible book HCF censored October 9, 2017 101 Cult Movies Steven Jay Schneider book EDCF censored September 17, 2014 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius Brad Graham & Kathy McGowan book HCF censored August 31, 2011 yes yes 9/27/2011 FY 12-009 110 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories & Stars: At this Theater Viagas & Botto Applause Theater & Cinema Books book LCF censored November 30, 2018 113 Minutes James Patterson Hachette books book -

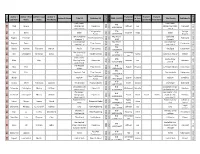

Type Author I Last Name Author I First Name Author II Last Name Author II

Translat Author I Author I First Author II Last Author II Translator Transl II Transl II Author III Name Title US Publisher US ISBN - US 1ED or First Title French Publisher Fr Type Last Name Name Name First Name Last Name Last Name First Name Month Year Fr Year US Name Trish Trash: Trish Trash, 978- Abel Jessica Rollergirl on Papercutz Johnson Joe rollergirl sur Mars Dargaud BD Nov. 2015 2016 1629916149 Mars (Vol.1) (Vol.1) Fantagraphics 978- Vertige B. David Babel Dascher Helge Babel BD Feb. 2004 Books 2016 1606999097 Graphic TBA (California NO INFO / California Bagieu Pénélope First Second Press Gallimard BD Oct. 2015 Dreamin’ ) 2016 2016 Dreamin’ Universal War NO INFO / Universal War Bajram Denis Titan Comics Casterman BD 2013 Two (Vol. 1) 2016 2016 Two (Vol.1) 978- Baudy Romain Trystram Martin Pacific Titan Comics Pacifique Casterman BD Dec. 2013 2016 1785856877 TBA (Siberia 56 978- Hahnenber Bec Christophe Sentenac Alexis Insight Comics Ivanka Siberia 56 (Vol.1) Glénat BD Oct. 2014 (Vol.1)) 2016 1608878611 ger Dance Class: 978- Studio danse Béka Crip Dancing in the Papercutz Johnson Joe Bamboo BD Dec. 2015 2016 1629911878 (Vol.9) Rain (Vol.9) The Nikopol 978- Bilal Enki Titan Comics Gauvin Edward La trilogie Nikopol Casterman BD Apr. 1992 Trilogy 2016 1782763536 978- Bilal Enki Century's End Titan Comics Fins de siècle Casterman BD Oct. 1983 2016 1782766810 New York Review 978- Blutch Peplum Gauvin Edward Péplum Cornélius BD Apr. 2000 Books 2016 1590179833 978- Camus Albert Ferrandez Jacques The Stranger Pegasus Books Smith Sandra L' Étranger Gallimard BD July 2013 2016 1681771359 The Sisters: Like 978- Les Sisters: Un air Cazenove Christophe Maury William Papercutz McGuiness Nanette Bamboo BD June 2008 Family (Vol.1) 2016 1629914930 de famille (Vol.1) The Sisters: Les Sisters : À la 978- Cazenove Christophe Maury William Doing It Our Papercutz Smith Annie Smith Owen mode de chez Bamboo BD Nov. -

Reference Document Annual Financial Report

Year 2008 Year Annual Financial Report Financial Annual including the including Reference Document including the Reference Document Document Reference Annual Financial Report Year 2008 www.lagardere.com Document prepared by the Corporate Communications Department This document is printed on paper from environmentally certifi ed sustainably PEFC/10-31-1222 managed forests. (PEFC/10-31-1222) 817_REFdoc_covHD_v4-c03_UK.indd 1 15/04/09 16:10 LAGARDÈRE SCA A French limited partnership with shares, with share capital of €799,913,044.60 divided into 131,133,286 shares of €6.10 par value each Head ofÞ ce: 4 rue de Presbourg - 75016 Paris (France) Commercial Register 320 366 446 RCS Paris website: www.lagardere.com Reference Document including the Annual Financial Report Year 2008 The original version of this Reference Document (Document de référence) in French was Þ led with the French Financial Market Authority (Autorité des Marchés Financiers - AMF) on 24 March 2009 in accordance with article 212-13 of the AMF Règlement Général (1). It may be used in connection with a Þ nancial transaction if completed by an Information notice approved by the AMF. (1) This is an English translation of the version which replaced the initial Reference Document fi led and made available online on 24 March 2009, and corrected the erroneous inclusion of a preliminary version of the Statutory Auditors’ report on internal control procedures in chapter 7, section 7-4-3-3, page 279. The fi nal version of that report, unchanged in substance, follows the model report recommended by the French National Institute of Statutory Auditors (Compagnie Nationale des Commissaires aux Comptes). -

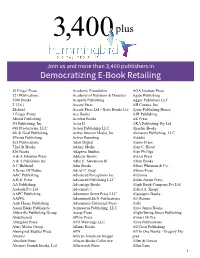

Democratizing E-Book Retailing

3,400 plus Join us and more than 3,400 publishers in Democratizing E-Book Retailing 10 Finger Press Academic Foundation AGA Institute Press 121 Publications Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics Agate Publishing 1500 Books Acapella Publishing Aggor Publishers LLC 2.13.61 Accent Press AH Comics, Inc. 2dcloud Accent Press Ltd - Xcite Books Ltd Ajour Publishing House 3 Finger Prints Ace Books AJR Publishing 3dtotal Publishing Acrobat Books AK Press 3G Publishing, Inc. Actar D AKA Publishing Pty Ltd 498 Productions, LLC Action Publishing LLC Akashic Books 4th & Goal Publishing Active Interest Media, Inc. Akmaeon Publishing, LLC 5Points Publishing Active Parenting Aladdin 5x5 Publications Adair Digital Alamo Press 72nd St Books Adams Media Alan C. Hood 826 Books Adaptive Studios Alan Phillips A & A Johnston Press Addicus Books Alazar Press A & A Publishers Inc Adlai E. Stevenson III Alban Books A C Hubbard Adm Books Albert Whitman & Co. A Sense Of Nature Adriel C. Gray Albion Press A&C Publishing Advanced Perceptions Inc. Alchimia A.R.E. Press Advanced Publishing LLC Alden-Swain Press AA Publishing Advantage Books Aleph Book Company Pvt.Ltd Aadarsh Pvt Ltd Adventure 1 Alfred A. Knopf AAPC Publishing Adventure Street Press LLC Algonquin Books AAPPL AdventureKEEN Publications Ali Warren Aark House Publishing Adventures Unlimited Press Alibi Aaron Blake Publishers Aepisaurus Publishing, LLC Alice James Books Abbeville Publishing Group Aesop Press Alight/Swing Street Publishing Abdelhamid Affirm Press Alinari 24 Ore Abingdon Press AFG Weavings LLC Alive Publications Abny Media Group Aflame Books All Clear Publishing Aboriginal Studies Press AFN All In One Books - Gregory Du- Abrams African American Images pree Absolute Press African Books Collective Allen & Unwin Abstract Sounds Books, Ltd. -

Mise En Page 1

25 March 2005 Convening notice Dear Shareholder, we are pleased to invite you to participate in the Combined General Meeting* of Lagardère SCA th On Tuesday 10 May 2005 at 10:00 a.m. at the Carrousel du Louvre 99, rue de Rivoli - 75001 PARIS, France The agenda and draft resolutions for this meeting are enclosed in this convening. 2 How to take part in the General Meeting? 4 Agenda * In accordance with legal provisions, 5 Draft resolutions presented the Combined General Meeting will convene for an initial session by the Managing Partners on Wednesday 27th April 2005 at 10:00 a.m., at 121 avenue de Malakoff, Paris 75016, France. The Meeting is likely to be unable to deliberate on this date, 15 Summary presentation due to the lack of quorum. Under these conditions, it shall therefore convene for a second session 43 Results of the last five on Tuesday 10th May 2005. financial years This English version of Lagardère convening notice has been prepared for the convenience of the English Language readers. It is a translation of the original “Avis de convocation”. It is intented for general information only and should not be considered as completely accurate owing to the unavailability of English equivalents for certain French legal terms. How to take part in the General Meeting? To take part in the meeting: Shareholders must be registered in the Company’s registered accounts at least five days before the meeting. If you wish to attend the meeting, please apply for an admission card in advance by returning All documents which, by law, are to be presented at general the duly completed and signed application form meetings shall be made available to shareholders within the attached, using the enclosed envelope, to the statutory time limits, either at the headquarters or at the following address: ARLIS LAGARDÈRE SCA securities department , ARLIS - 6, rue Laurent- 6, rue Laurent-Pichat Pichat, Paris 75016, France. -

London Rights Guide 2018 the Orion Publishing Group London Rights Guide 2018

LONDON RIGHTS GUIDE 2018 THE ORION PUBLISHING GROUP LONDON RIGHTS GUIDE 2018 CONTENTS Fiction .......................................................... 1 Gollancz.................................................. 53 Non-Fiction ........................................... 81 Illustrated Non-Fiction .................... 127 Orion Rights: Contact Details GENERAL ENQUIRIES Tel: + 44(0)20 3122 6444 www.orionbooks.co.uk [email protected] US RIGHTS Susan Howe – Group Rights & Audio Director Direct line: +44(0)20 3122 6905 [email protected] Jessica Purdue – Senior Rights Manager Direct line: + 44(0)20 3122 6838 [email protected] TRANSLATION RIGHTS Chinese (simplified and complex), Dutch, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean and Spanish language rights Krystyna Kujawinska – Foreign Rights Director Direct line: + 44(0)20 3122 6853 [email protected] Croatian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Serbian and Slovenian language rights Jessica Purdue – Senior Rights Manager Direct line: + 44(0)20 3122 6838 [email protected] Arabic, Bulgarian, Czech, Estonian, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Romanian, and Turkish language rights Richard King – Rights Manager Direct line: +44(0)20 3122 6886 [email protected] Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian & Swedish language rights Hannah Stokes– Senior Rights Executive Direct line: +44(0)20 3122 6823 [email protected] TV AND FILM RIGHTS Susan Howe – Group Rights & Audio Director Richard King – Rights Manager