Freedom Struggles © Kamala Jackson 2009-10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lighting Without Power

Lighting Without Power Kerosene and oil lamps are another option prone to accidents. The flame is contained within the lantern so it's a little safer than a candle's open flame, and the amount of light provided is better than a single candle. On the other hand, kerosene and lamp oil are highly poisonous, must be stored out of the reach of children, tend to get very hot, and need to be stored away from accidental ignition sources. [We store ours in an insulated and latched picnic cooler, which helps protect them from ignition sources and contains any mess if they are broken in an earthquake.] Propane lamps are another option, but like other liquid fuel lamps, are not recommended for indoor use because of the risk of carbon monoxide build-up. They also need a good reserve of fuel if they are your choice for an emergency. LED battery-operated lanterns or flashlights are the safest choices for emergencies. Flashlights are better for finding your way around in the dark, while battery-operated lanterns are best for ambient room light. The best models have both options built into one light. There are expensive models, but there are also very reasonable models if budget is an issue. Headlamps are a great way to be able to provide focused, hands-free task lighting. Most people don't have these, but this is probably the best bed-side emergency lighting you can have. That way, if a fire, earthquake or tornado happens, you have two free hands to crawl, move debris, administer first aid, or pick up your child as needed. -

1 Description

Operating Manual for hipFlex UIF, UIP & UIB2 (V1.00b) 1 Description The heart of hipFlex is a Microcontroller (uC) that contains the user interface firmware. Features of this circuit/UI combination include: • Choice of 3 different User Interfaces, UIF fixed lighting optimized, UIP portable lighting optimized and UIB2 bicycle lighting optimized. • High efficiency Buck mode (step down) switching regulator (maximum drive current set in firmware). Reverse polarity protected. • Single switch to select from various brightness levels, turn the unit on/off, select the operating modes and set menu options. • Non-volatile (EEPROM) storage of operating mode, last selected brightness level, and maximum drive level (1000mA, 1400mA, 2000mA, 2400mA or 2800mA). • Voltage sensing with three user configurable trip points for ½ discharged and nearly fully discharged and forced off (or warn only). Warning display via an optional 3mm or 5mm status LED or via the main LED. • Temperature sensing with user configurable trip point to limit output current to protect the driver and/or LED. 1.1 Wiring the hipFlex The picture shows the connections to hipFlex. The user provides DC power to the hipFlex (via battery, DC wallwart, vehicle/boat/RV 12V. hipFlex is reverse polarity protected with a low drop out FET (less than 50mV voltage drop across the FET). hipFlex requires a user provided momentary action switch that must be connected via leads soldered to the holes SWA and SWB. The switch needs to be a momentary action, push to close type, i.e. normally open contacts. Input power is connect via IN+ (positive input voltage) and IN- (negative input voltage). -

A. Repiort of a Joint Project Toy Hea.Lt3a Service Staff Oons-U.Lt Struts

.A. repiort of a joint project Toy Hea.lt3a Service staff oons-u.lt struts U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE Public Health Service Division of Hospital and Medical Facilities Architectural and Engineering Branch Washington 25, D.C. PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE PUBLICATION NO. 930-D-3 October 1962 For salt! by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. Price 35 cents. The provision of optimum lighting conditions in patient rooms is an important element in the design of hospital and related medical facilities. In determining lighting requirements, consideration should be given not only to the patient's personal needs and comfort but also to activities which take place in the patient's room, such as nursing care, medical examinations, test procedures, and housekeeping. When this Hill-Burton Program activity was undertaken in 1956, the primary aims were to determine lighting requirements and to develop light- ing levels that might serve as criteria for illumination of patient rooms. As the study progressed, the need was recognized for enlarging the scope of the project to include a study on how the lighting requisites might be met most economically and satisfactorily for both the patient and the hospital staff. Consequently, continuation of the project was authorized on this basis; the studies are referred to as Part I and Part II. The recommendations in this report are based on an evaluation of the many problems concerning artificial illumination in patient rooms in general hospitals. The many factors which increase or lessen the reflectance or brightness of light such as wall color and luminaire design are discussed in some detail, It is hoped that the findings of these studies will he useful as guidelines for architects, engineers, and others concerned with the design of lighting systems for hospital patient rooms. -

OLED Lighting in the Offices of Dejoy, Knauf & Blood

OLED Lighting in the Offices of DeJoy, Knauf & Blood, LLP Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy Solid-State Lighting Program July 2017 Prepared by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory PNNL- 26642 OLED Lighting in the Offices of DeJoy, Knauf & Blood, LLP Final report prepared in support of the U.S. DOE Solid-State Lighting Technology GATEWAY Program Study Participants: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory DeJoy, Knauf & Blood, LLP, Certified Public Accountants, Rochester NY Naomi J. Miller July 2017 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Preface The U.S. Department of Energy’s Solid-State Lighting program documents the performance of SSL products and systems based on standardized laboratory test results, additional specialized testing, mock- up studies, and real-world field evaluations. This information is provided publicly for several purposes: 1) to track SSL technology performance improvement over time; 2) to identify technology challenges that impact performance and application of SSL; 3) to spur continued advancements in SSL technology, product design, and application; and 4) to maximize energy efficiency and decrease US energy use, while improving lighting quality. DOE does not endorse any commercial product or in any way provide assurance that other users will achieve similar results through use of these products. SSL technology continues to evolve quickly, so evaluation results should always be understood in the context of the timeframe in which products were acquired, tested, installed, and operated. Especially given the rapid development cycle for SSL products, specifiers and purchasers should always seek current information from manufacturers when evaluating such products. -

User's Manual Table of Contents 1 Overview of Components

User's Manual Table of contents 1 Overview of components ................................................................................. 54 1.1 Display and control unit..................................................................... 54 1.2 Battery pack and charger.................................................................. 55 2 Battery pack .................................................................................................... 56 2.1 Charging instructions ........................................................................ 56 2.2 Charging the battery pack................................................................. 58 2.3 Installing the battery pack ................................................................. 59 h s 2.4 Removing the battery pack .............................................................. 59 i l g 2.5 Security ............................................................................................. 60 n 2.6 Connect module ................................................................................ 60 E 2.7 Diagnosis message........................................................................... 61 3 Display ION ..................................................................................................... 62 3.1 Removing and fixing ......................................................................... 62 3.2 Adjustment ........................................................................................ 62 3.3 Overview of buttons and indications ................................................ -

Energy Efficient Lighting

Energy Efficient Lighting Electric lighting is a major energy consumer. Enormous energy savings are possible using energy efficient equipment, effective controls, and careful design. Using less electric lighting reduces heat gain, thus saving air-conditioning energy and improving thermal comfort. Electric lighting design also strongly affects visual performance and visual comfort by aiming to maintain adequate and appropriate illumination while controlling reflection and glare. Lighting is not just a high priority when considering hotel design; it is also a high- return, low-risk investment. By installing new lighting technologies, hotels can reduce the amount of electricity consumed and energy costs associated with lighting. There are several types of energy efficient lighting and affordable lighting technology. The following are a few examples of energy-saving opportunities with efficient lighting. 1. INSTALLATION OF COMPACT FLUORESCENT LAMPS (CFLS) IN PLACE OF INCANDESCENT LAMPS. Compact Fluorescent Lamps use a different, more advanced technology than incandescent light bulbs and come in a range of styles and sizes based on brand and purpose. They can replace regular, incandescent bulbs in almost any light fixture including globe lamps for the bathroom vanity, lamps for recessed lighting, dimming, and 3-way functionality lights. CFLs use about 2/3 less energy than standard incandescent bulbs, give the same amount of light, and can last 6 to 10 times longer. CFL prices range from $4 to $15 depending on the bulb, but you save about $25 to $30 per bulb on energy during the lifetime of the bulb. When looking to purchase CFLs in place of incandescent bulbs, compare the light output, or Lumens, and not the watts. -

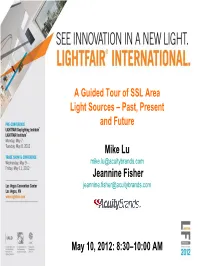

A Guided Tour of SSL Area Light Sources – Past, Present and Future

A Guided Tour of SSL Area Light Sources – Past, Present and Future Mike Lu [email protected] Jeannine Fisher [email protected] May 10, 2012: 8:30–10:00 AM 1 Learning objectives 1. Fundamental principles of luminescence 2. Technologies for area SSL sources 3. Metrics and how these technologies compare 4. What of applications they enable and how they will impact future luminaire design ! Throughout this seminar, we’ll use me k at Loo symbols to call out key concepts and common threads. 2 Overview Why area light source (JF) Introduction Metrics SSL area sources and technologies (ML) Basic Physics Detailed examples Summary Lighting Application (JF) Conclusions 3 Why area light source 4 Architecture: Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart and Associates Lighting: Terry Bell / CD+M Lighting Design Group,5 LLC Photography: Paul Warchol 5 Architecture: Gensler Lighting: Darrell Hawthorne / Architecture & Light Photography: Nic Lehoux 6 Architecture: Centerbrook Architects and Planners Lighting: ARUP / Atelier Ten Photography: Robert Benson 7 Lighting: Jeff Wilson / Phos Lighting Photography: Ashley Campbell 8 Design Intent: Illuminate grand space using curved luminous surface to accentuate architecture Luminaire: Wall-mounted indirect ceramic metal halide Lamping: 2 – 400W ED28 Luminaire efficacy: 70 lm/W Implementation: Each luminaire Project: McCormick Convention Center Architecture: Thompson, Ventulett, Stainback & Associates, Inc. weighs over 60 lbs and requires 2 Lighting: Fisher Marantz Stone, Inc. Photography: Steve -

Developing the Means for the Use of Modern Lighting: How Can WLED Technology Bring High Quality, Affordable Light to India’S Poor?

Developing the Means for the Use of Modern Lighting: How can WLED technology bring high quality, affordable light to India’s poor? Joshua Apte, Energy and Resources Group, MS Merrian Fuller, Haas School of Business, MBA Anand Gopal, Energy and Resources Group, PhD Katie Lindgren, Haas School of Business, MBA Faculty Advisors: Daniel Kammen, Professor, Energy and Resources Group Ashok Gadgil, Adjunct Professor, Energy and Resources Group Technical Advisor: Evan Mills, Staff Scientist, Environmental Energy Technologies Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Final Report to the Bridging the Divide Fellowship Program University of California, Berkeley December 22, 2007 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Project Summary & Research Questions 4 Study Design 4 Technical product testing 5 Product selection 10 Field research & survey design 11 Results 12 Existing lighting conditions 12 Exit Survey Results 17 Recommendations 18 a. Products 18 b. Pricing & Business Model 19 c. Sales and Distribution 21 Lessons learned from field work 21 Areas that need further research 22 Appendix A – Community-level Survey 24 Appendix B – Household Initial Survey 27 Appendix C – Household Exit Survey 33 Appendix D – Willing to Pay (Individual Responses by Product) 38 Appendix E – Exit Survey: Changes in existing product use with WLED product 39 Appendix F – Test results of field-tested lighting products 40 2 Executive Summary India is home to one-third of the world’s unelectrified population. The vast majority of these people obtain their basic lighting needs from fuel-based technology such as kerosene lanterns. The energy efficiency and downward scalability of white light emitting diodes (WLEDs) make them an excellent candidate to be a leapfrog technology, much like cell phones, for the rural developing world. -

Quantitative Analysis of VIIRS DNB Nightlight Point Source for Light Power Estimation and Stability Monitoring

Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 11915-11935; doi:10.3390/rs61211915 OPEN ACCESS remote sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Quantitative Analysis of VIIRS DNB Nightlight Point Source for Light Power Estimation and Stability Monitoring Changyong Cao 1,* and Yan Bai 2 1 NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)/NESDIS (National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service)/STAR (Center for Satellite Applications and Research), NCWCP, E/RA2, 5830 University Research Ct., Suite 2838, College Park, MD 20740, USA 2 CICS(Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites), ESSC Building, RM3250, University of Maryland, 5825 University Research Ct. College Park, MD 20740, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-683-3600; Fax: +1-301-683-3616. External Editors: Christopher D. Elvidge and Prasad S. Thenkabail Received: 10 September 2014; in revised form: 18 November 2014 / Accepted: 18 November 2014 / Published: 1 December 2014 Abstract: The high sensitivity and advanced onboard calibration on the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Day/Night Band (DNB) enables accurate measurements of low light radiances which leads to enhanced quantitative applications at night. The finer spatial resolution of DNB also allows users to examine social economic activities at urban scales. Given the growing interest in the use of the DNB data, there is a pressing need for better understanding of the calibration stability and absolute accuracy of the DNB at low radiances. The low light calibration accuracy was previously estimated at a moderate 15% using extended sources while the long-term stability has yet to be characterized. -

US 2006/0221594 A1 Thuot Rann Et Al

US 20060221594A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0221594 A1 Thuot Rann et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 5, 2006 (54) MULTI-CLARITY LENSES Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Raechell Maria Thuot Rann, Racine, F2IV 33/00 (2006.01) WI (US): Imre J. Dancs, Greenfield, F2IV 5/00 (2006.01) WI (US); John S. Trent, Franklin, WI (52) U.S. Cl. ............................. 362/96; 362/332: 362/253 (US) (57) ABSTRACT The present invention is directed toward apparatuses, devices, methods, kits, programs, and combinations to dis Correspondence Address: perse and/or project light. For example, in one embodiment S.C. JOHNSON & SON, INC. of the present invention where a light effect of glowing, 1525 HOWE STREET diffuse, and projected light is desired, one lens is provided RACINE, WI 53403-2236 (US) that diffuses light in one section of the lens and is Substan tially clear in another section to allow substantially all the light to pass through the lens. In other embodiments to (21) Appl. No.: 11/097,770 obtain the same effect, one or more lenses diffuse light while one or more other lenses are clear to allow substantially all (22) Filed: Mar. 31, 2005 the light to pass through the lens. 20 38 52b 25a 25 53 53a 51 100 Patent Application Publication Oct. 5, 2006 Sheet 1 of 16 US 2006/0221594 A1 Patent Application Publication Oct. 5, 2006 Sheet 2 of 16 US 2006/0221594 A1 Fig. 2 J U. NSH-12 sa Patent Application Publication Oct. 5, 2006 Sheet 3 of 16 US 2006/0221594 A1 Fig. -

Light Sources Secondary Light Sources Eyes Brain Generators – Modifiers and Re-Transmitters Receivers – Decoder – Transmitters Encoders Interpreter

Light Sources Secondary Light Sources Eyes Brain Generators – Modifiers and Re-transmitters Receivers – Decoder – Transmitters Encoders Interpreter Sun, Discharge lamps, Atmosphere, Air, Water, Planets, Lenses, Cornea, Iris, Lens, Analysis, fluorescent lamps. Windows, Tress – All natural or manufactured Rods & Cones, Identification Incandescent lamps, objects which modify light waves before they Optic Nerves Association Open flames, etc. reach the eye. Perception 1 Controlling Light 2 Light = Color 3 What is Light? Light is a form of energy that is part of the electromagnetic spectrum visible to the human eye. 4 Light = Color 5 Color Mixing 6 Light = Color Colors by Addition Colors by Subtraction Mixture of Light Mixture of Pigments 7 What is Light? There are two different ways of talking about light: There is the "particle" theory, expressed in part by the word photon. There is the "wave" theory, expressed by the term light wave. 9 Light = Energy Waves 10 Light = Color Spectral Power Distribution Curves (SPD) provide the user with a visual profile of the color characteristics of a light source. They show the radiant power emitted by the source at each wavelength or band of wavelengths over the visible region (380 to 760 nm). 11 Light = Color Daylight at Noon Afternoon Sun Full Moon Tubular Candle Fluorescent Incandescent Compact Fluorescent 12 Metal Halide High Pressure Sodium (indigo nightlight) PC Monitor PC Laptop 13 Color Spectrum Night Morning Afternoon Late Afternoon Night Incandescent Lamps and Natural Daylight produce smooth, continuous spectra. 14 Daylight Color Spectrum Passenger (stills), video projection, 2004 Jutta Strohmaier For Passenger, Strohmaier photographed the same spot every minute for three days. -

Circle of Light

Circle of Light The impact of the LED Lifecycle Savannah Carr-Wilson, Elizabeth Drachenberg, Gabrielle Freeman, Ritika Jain, Robyn Kotze, Malgorzata Lekan, Sunanda Mehta, Dann Moreno, Darja Mihailova, Brayton Noll, Sandeep, Sai Siddhartha Nandamuri, Marula Tsagkari, Rongyu Veneta Tzeng Partly funded by: Research by: Cover page designed by Malgorzata Lekan This publication should be cited as: International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics [IIIEE]. (2016). Circle of Light. The impact of the LED Lifecycle. Lund: IIIEE. ISBN 978-91-87357-27-5 CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………...2 4 Lighting the Paths for Eco-Design: Life Cycle Assessment of Light Sources Malgorzata Lekan 36 Rongyu Veneta Tzeng 12 The After-Light: Digging for Truth: Raw Material The Today and Tomorrow of LED Extraction and Future Potential for LEDs End-of-Life Elizabeth Drachenberg Management Darja Mihailova Savannah Carr-Wilson Sai Siddhartha Nandamuri Gabrielle Freeman Sandeep 28 21 This Little Light of Manufacturing of Mine: Use and LEDs: A Take on Distribution of the Technology LEDs and its Impacts Dann Moreno Ritika Jain Brayton Noll Robyn Kotze Marula Tsagkari Sunanda Mehta Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………44 The IIIEE……………………………………...……………………………......45 The Authors …..……..……..……..……..……..……..……..……..……..……...46 CIRCLE OF LIGHT Introduction Why a Life Cycle Approach to LEDs is Needed his report Circle of Light. The impact of the By following a LED light through its life cycle, T LED Lifecycle uses a life cycle framework some concerns regarding the sustainability of to explore the different phases of Light- such products, often founded in a lack of Emitting Diode (LED) lights. The information knowledge, can be addressed. This report ad- presented in the report will be useful to public dresses impacts from the four stages: raw ma- and private stakeholders as they get ready to terial extraction, manufacturing, use and distri- invest in transformative LED solutions.