Read the Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumnae Colleges and Universities

Alumnae Colleges and Universities Alaska: Florida: • University of Alaska • Eckerd College • Florida Atlantic University Alabama: Georgia: • Auburn University • Augusta University Arizona: Iowa: • Northern Arizona University • Prescott College • Grinnell College • University of Iowa California: Idaho: • American Music and Dramatic Academy • University of Idaho • California Polytechnic State Illinois: University • City College of San Francisco • Northwestern University • Loyola Marymount University • Mills College Kansas: • Pitzer College • San Francisco State University • University of Kansas • Scripps College • Stanford University Kentucky: • University of California – Berkeley • Frontier Nursing University Colorado: Louisiana: • Art Institute of Colorado • Colorado College • Tulane University • Colorado State University • Colorado University Boulder Massachusetts: • Denver School of Nursing • Naropa University • Assumption College • University of Colorado • Boston College • University of Denver • Boston University • Hampshire College Connecticut: • Harvard University • Mount Holyoke College • Wesleyan University • Tufts University • Yale University Maryland: • University of New Mexico • St. John’s College New York: Maine: • Barnard College • Colgate University • Bates College • Columbia University • Bowdoin College • Cornell University • College of the Atlantic • Global College of Long Island University Michigan: • Hamilton College • New York School of Interior Design • Kalamazoo College • New York University • Michigan State University -

College Counseling Program

College Counseling Program The Oregon Episcopal School college counseling team works closely with students as they search for colleges in which they will thrive. Encouraging them to take ownership of the experience, we combine individualized advice with programs and resources designed to help students—and their families—navigate the search and application phases in a thoughtful manner. Throughout high school, we provide guidance, perspective, and timely information intended to demystify the process and encourage wise choices. Underpinning our approach is a desire to have students make the most of their high school experience in a healthy, balanced manner. COLLEGE NIGHTS FOR PARENTS We offer workshops for parents, tailored by grade level, to learn about the college search process, and a presentation on financing college. For more information, visit: COLLEGE ATTENDANCE oes.edu/college Graduates of OES attend an impressive array of colleges throughout the United States and internationally. OES has an excellent, well-established reputation with colleges across the country and hosts visits from over 130 college representatives in a typical year. Colleges Attended Public vs. Private Public 29% 71% Private Non U.S.: 4% Admissions 6300 SW Nicol Road | Portland, OR 97223 | 503-768-3115 | oes.edu/admissions OES STUDENTS FROM THE CLASSES OF 2020 AND 2021 WERE ACCEPTED TO THE FOLLOWING COLLEGES Acadia University Elon University Pomona College University of Chicago Alfred University Emerson College Portland State University University of Colorado, -

Landmark School Class of 2016 List of College Acceptances Adelphi

Landmark School Class of 2016 List of college acceptances Adelphi University Hampshire College Allegheny College Hawaii Pacific University American University High Point University Arcadia University Hobart and William Smith Assumption College Hofstra University Becker College Hope College Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology Iona College Bishops University Ithaca College Bridgewater State University James Madison University Bryant University Johnson & Wales University Bucknell University Johnson State College Castleton University Keene State College Catholic University of America Kettering University Champlain College Lake Forest College Citadel Landmark College Clark University Lasell College Clarkson University Lehigh University Coastal Carolina University Lesley University Colby-Sawyer College Liberty University College of Charleston Long Island University/Brooklyn College of the Atlantic Long Island University/CW Post Colorado Mountain College Loyola University Maryland Curry College Lynchburg College Dean College Lyndon State College DePaul University Lynn University Drexel University Maine Maritime Academy Elon University Manhattanville College Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Marist College Emerson College Maryland Institute College of Art Emmanuel College Marymount Manhattan College Endicott College Massachusetts College of Art and Design Fairfield University Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts Fitchburg State University Massachusetts Maritime Academy Florida Institute of Technology McDaniel College Framingham State -

Students in Our Class of 2021 Have Already Been Admitted to These Schools

Students in our Class of 2021 have already been admitted to these schools: University of Akron Georgia Tech University of Redlands Allegheny College Gettysburg College Rhode Island School of Design American University University of Hawaii University of Richmond American University of Paris High Point University Roanoke College Amherst College Hofstra University Rollins College University of Arizona Houghton College Rose-Hulman Institute of Arizona State University University of Illinois Technology Babson College Indiana University Rutgers University Barnard College James Madison University University of San Francisco Bates College University of Kansas Santa Clara University Belmont University Kansas State University Seton Hall University Berea College Kent State University Smith College Boston College University of Kentucky University of the South Boston University Lewis & Clark College University of South Carolina University of British Columbia Loyola University Chicago University of South Florida Bucknell University Marshall University Southern Methodist University Butler University University of Maryland Spelman College Capital University University of Massachusetts- St. Catherine University Carleton College Amherst St. Francis College Carnegie Mellon University Massachusetts Institute of St. John’s University-New York Case Western Reserve Technology (MIT) St. Lawrence University University University of Massachusetts- St. Olaf College Catholic University of America Lowell Stanford University Central State University Merrimack College -

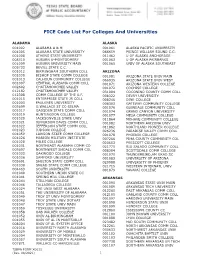

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

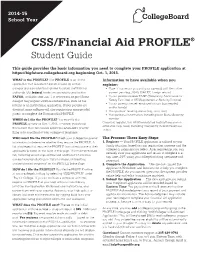

CSS/Financial Aid PROFILE® Student Guide

2014-15 School Year CSS/Financial Aid PROFILE® Student Guide This guide provides the basic information you need to complete your PROFILE application at https://bigfuture.collegeboard.org beginning Oct. 1, 2013. WHAT is the PROFILE? The PROFILE is an online Information to have available when you application that collects information used by certain register: colleges and scholarship programs to award institutional • Type of tax return you and your parent(s) will file for the aid funds. (All federal funds are awarded based on the current year (e.g., 1040, 1040 EZ, foreign return) FAFSA, available after Jan. 1 at www.fafsa.ed.gov.) Some • If your parents receive TANF (Temporary Assistance for colleges may require additional information, such as tax Needy Families) or SSI (Supplemental Security Income) • If your parents are self-employed or own business(es) returns or an institutional application. If your parents are and/or farm(s) divorced, some colleges will also require your noncustodial • Your parents’ housing status (e.g., own, rent) parent to complete the Noncustodial PROFILE. • Your personal information, including your Social Security WHEN do I file the PROFILE? You may file the number PROFILE as early as Oct. 1, 2013. However, you should Once you register, you will find detailed instructions and an extensive Help Desk, including Frequently Asked Questions, file no later than two weeks before the EARLIEST priority online. filing date specified by your colleges or programs. WHO must file the PROFILE? Check your colleges’/programs’ The Process: Three Easy Steps information to determine whether they require the PROFILE. A 1. -

2007/2008 Catalog Ohio Wesleyan University Contents

2007/2008 Catalog Ohio Wesleyan University Contents Contents While this Catalog presents the best information available at the time of publication, all information contained herein, including statements of fees, course offerings, admission policy, and graduation requirements, is subject to change without notice or obligation. Calendar ......................................................................................................inside back cover The University ......................................................................................................................4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................4 Statement of Aims ............................................................................................................5 Intellectual Freedom and Responsibility ..........................................................................6 Statement on Student Rights ............................................................................................7 The Affirmative Action Plan.............................................................................................8 Policy on Sexual Harassment ...........................................................................................8 Policy on Voluntary Sexual Relationships between Faculty/Staff and Students ..............9 Traditions ........................................................................................................................12 -

The Inauguration of Thomas H. Kean As Tenth President

THE INAUGURATION OF THOMAS H. KEAN AS TENTH PRESIDENT OF DREW UNIVERSITY FRIDAY, THE TWENTIETH OF APRIL NINETEEN HUNDRED AND NINETY TWO O'CLOCK IN THE AFTERNOON ON THE CAMPUS MADISON, NEW JERSEY D R E W UNIVERSITY: A P E R S P E C T I V E Built by renowned scholars, supported by people of vision, nurtured by dedicated leaders, and located on a beautiful tract of land long known as The Forest, Drew University is uniquely poised in its history become a national leader in higher education, for in recent decades Drew has made innovation and distinction the watch- words of its identity. Drew's innovative streak may stem from its birthright. Founded in 1866 as a seminary for the Methodist Epis- copal Church in America, the school was endowed by Daniel Drew with what was at the time the largest gift to American higher education. The financier, whose early cattle dealings gave birth to the original meaning of " watered stock," managed the school's endowment through stock manipulations and speculation until in 1875 his practices nearly bankrupted the young seminary. That crisis necessitated administrative resourcefulness and faculty sacrifice to keep the school open. However uncertain its beginnings, Drew has since grown into a university whose programs--from the Bachelor of Arts to the Master of Divinity to the Doctor of Philosophy--are distinguished by an emphasis on intimate learning and teaching. Drew's three schools--the College of Liberal Arts (1,500 students), the Graduate School ( 350), and the Theological School (350)--share an insistence on academic rigor and a student-centered philosophy that has educated nearly 14,000 living alumni and alumnae. -

CAREER OPPORTUNITIES and BISHOP BAXTER's ADVICE While I

CAREER OPPORTUNITIES AND BISHOP BAXTER'S ADVICE While I was teaching at Willamette University, President Bruce Richard Baxter often gave me special assignments. I did not know it then but he was actually giving me some administrative experience. Frequently, he would say to me, "Frank, if you had this kind of problem, how would you solve it?" It was fun for me and I would reply that I would do this and this and this. Quite often, he would then say, "Don't you see the political implications and the business implications if you do that? What are the alternatives?" And we would discuss them, and I learned a great deal from him regarding administrative management. At the same time, 1\Trs. Baxter often invited Lucille to the President's home to help entertain visitors--trustees, executives from the East, lecturers, and other unusual and interesting people. Both of us learned a very great deal about administration without being aware of it. When I was offered the position at the College of Puget Sound, I went up to Portland to see Dr. Baxter, who by then was Bishop of the Portland Area, and I always remembered what he told me: "Frank, you will have many unusual experiences if you accept, and you will have sore temptations to leave for some other place after a certain length of time. I think there is something to be said for a president who gives his entire, active life to one institution's development. He achieves something that cannot be derived if he only stays at one place for two or three years and then departs for somewhere else." - 2- Lucille and I talked it over and decided that we would follow Bishop Baxter's advice and go to a school like the College of Puget Sound and give our lives to its development and to the young people with whom we would be associated. -

Institutional Respondents to the Online Survey

Alternative IT Sourcing Strategies ECAR Research Study 5, 2009 Appendix A Institutional Respondents to the Online Survey Acadia University Bradley University Allegheny College Brazosport College Alliant International University–San Diego Brenau University Antioch University System Administration Bridgewater State College Arcadia University Brigham Young University Hawaii Asbury College British Columbia Institute of Technology Assumption College Brock University Athabasca University Broome Community College Atlantic Cape Community College Caldwell College Atlantic Union College California State University, East Bay Auburn University at Montgomery California State University, Fullerton Azusa Pacific University California State University, Monterey Bay Baker University California State University, Northridge Baltimore City Community College California State University, Sacramento The Banff Centre Calvin College Bard College at Simon’s Rock Camosun College Barnard College Campbell University Bates College Canadian University College Baylor University Canisius College Benedict College Cardinal Stritch University Benedictine University Carroll University Berry College Case Western Reserve University Bethel University Catawba College Birmingham-Southern College Central Connecticut State University Black Hills State University Central Michigan University Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania Central Piedmont Community College Blue Ridge Community and Technical Charter Oak State College College Chicago State University Bluefield State College Christopher -

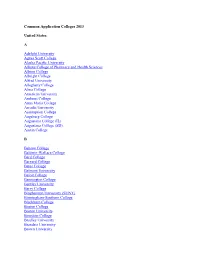

Common Application Colleges 2013 United States: a Adelphi University

Common Application Colleges 2013 United States: A Adelphi University Agnes Scott College Alaska Pacific University Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Albion College Albright College Alfred University Allegheny College Alma College American University Amherst College Anna Maria College Arcadia University Assumption College Augsburg College Augustana College (IL) Augustana College (SD) Austin College B Babson College Baldwin-Wallace College Bard College Barnard College Bates College Belmont University Beloit College Bennington College Bentley University Berry College Binghamton University (SUNY) Birmingham-Southern College Blackburn College Boston College Boston University Bowdoin College Bradley University Brandeis University Brown University Bryant University Bryn Mawr College Bucknell University Buffalo State (SUNY) Burlington College Butler University C Caldwell College California College of the Arts California Institute of Technology (Caltech) California Lutheran University Calvin College Canisius College Carleton College Carnegie Mellon University Carroll College (Montana) Carroll University Case Western Reserve University Castleton State College Catholic University of America Cazenovia College Cedar Crest College Centenary College (New Jersey) Centenary College of Louisiana Central Connecticut State University Centre College Champlain College Chapman University Chatham University Christian Brothers University Christopher Newport University Claremont McKenna College Clark University Clarkson University Coe College Colby -

Oregon Episcopal School College Visits (2018-19)

Oregon Episcopal School College Visits (2018-19) Amherst College Harvey Mudd College Salve Regina University Bard College Haverford College Santa Clara University Bard College Berlin Hobart and William Smith Sarah Lawrence College Barnard College Colleges Skidmore College Bates College Hofstra University Smith College Beloit College Johns Hopkins University Southern Methodist University Bennington College Kalamazoo College Southwestern University Boston University Kenyon College St. Edward's University Brandeis University Lafayette College St. Olaf College Brown University Lake Forest College Syracuse University Bucknell University Lehigh University The College of Wooster Carnegie Mellon University Linfield College The George Washington Case Western Reserve University Loyola Marymount University University Claremont McKenna College Loyola University New Orleans The New School - All Divisions Clark University Lynn University Trinity College Colby College Macalester College Trinity University Colgate University Maryland Institute College of Art Tufts University College of the Holy Cross Marymount California University Union College, New York Colorado College Massachusetts Institute of University of British Columbia Columbia University Technology University of California, Concordia University, Irvine McDaniel College Los Angeles Concordia University, Portland Menlo College University of California, San Diego Connecticut College Mount Holyoke College University of Chicago Corban University Muhlenberg College University of Colorado at Boulder