Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Strandloper by Alan Garner Strandloper by Alan Garner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scholarship Boys and Children's Books

Scholarship Boys and Children’s Books: Working-Class Writing for Children in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s Haru Takiuchi Thesis submitted towards the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics, Newcastle University, March 2015 ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores how, during the 1960s and 1970s in Britain, writers from the working-class helped significantly reshape British children’s literature through their representations of working-class life and culture. The three writers at the centre of this study – Aidan Chambers, Alan Garner and Robert Westall – were all examples of what Richard Hoggart, in The Uses of Literacy (1957), termed ‘scholarship boys’. By this, Hoggart meant individuals from the working-class who were educated out of their class through grammar school education. The thesis shows that their position as scholarship boys both fed their writing and enabled them to work radically and effectively within the British publishing system as it then existed. Although these writers have attracted considerable critical attention, their novels have rarely been analysed in terms of class, despite the fact that class is often central to their plots and concerns. This thesis, therefore, provides new readings of four novels featuring scholarship boys: Aidan Chambers’ Breaktime and Dance on My Grave, Robert Westall’s Fathom Five, and Alan Garner’s Red Shift. The thesis is split into two parts, and these readings make up Part 1. Part 2 focuses on scholarship boy writers’ activities in changing publishing and reviewing practices associated with the British children’s literature industry. In doing so, it shows how these scholarship boy writers successfully supported a movement to resist the cultural mechanisms which suppressed working-class culture in British children’s literature. -

Steam Engine Time 7

Steam Engine Time Everything you wanted to know about SHORT STORIES ALAN GARNER HOWARD WALDROP BOOK AWARDS HARRY POTTER Matthew Davis Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Bruce Gillespie David J. Lake Robert Mapson Gillian Polack David L. Russell Ray Wood and many others Issue 7 October 2007 Steam Engine Time 7 If human thought is a growth, like all other growths, its logic is without foundation of its own, and is only the adjusting constructiveness of all other growing things. A tree cannot find out, as it were, how to blossom, until comes blossom-time. A social growth cannot find out the use of steam engines, until comes steam-engine time. — Charles Fort, Lo!, quoted in Westfahl, Science Fiction Quotations, Yale UP, 2005, p. 286 STEAM ENGINE TIME No. 7, October 2007 is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia ([email protected]) and Janine Stinson, PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248, USA ([email protected]). Members fwa. First edition is in .PDF file format from http://efanzines.com, or enquire from either of our email addresses. In future, the print edition will only be available by negotiation with the editors (see pp. 6–8). All other readers should (a) tell the editors that they wish to become Downloaders, i.e. be notified by email when each issue appears; and (b) download each issue in .PDF format from efanzines.com. Printed by Copy Place, Basement, 415 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000. Illustrations Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front cover); David Russell (p. 3). Photographs Covers of various books and magazines discussed in this issue; plus photos by Cath Ortlieb (p. -

The Mythological Archetypes and the Living Myth in Alan Garner's the Owl Service

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diponegoro University Institutional Repository THE MYTHOLOGICAL ARCHETYPES AND THE LIVING MYTH IN ALAN GARNER’S THE OWL SERVICE A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For S-1 Degree Majoring in Literature in English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Atikah Rahmawati 13020114130072 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2019 i PRONOUNCEMENT The writer states truthfully that this project is compiled by herself without taking any results from other research in any university, in S-1, S-2, S-3 degree and diploma. In addition, the writer ascertains that she did not take material from other publication or someone’s work except for the references mentioned in the bibliography. Semarang,4 October 2019 Atikah Rahmawati ii MOTTO AND DEDICATION “Everything works out in the end” – Kodaline This final project is dedicated to me, my parents, and my friends. iii APPROVAL THE MYTHOLOGICAL ARCHETYPES AND THE LIVING MYTH INALAN GARNER’S THE OWL SERVICE Written by: Atikah Rahmawati NIM: 13020114130072 Approved by, Thesis Advisor Drs. SiswoHarsono, M.Hum. NIP. 19640418199001001 The Head of the English Department, Dr. AgusSubiyanto, M.A. NIP. 196408141990011001 iv VALIDATION Approved by Strata 1 Thesis Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University On 4October 2019 Chair Person First Member Dra. Astri Adriani Allien, M.Hum Ariya Jati, S.S, M.A NIP. 196006221989032001 NIP. 197802282005021001 Second Member Third Member Dra. R. AJ. Atrinawati, M.Hum Drs. Catur Kepirianto, M.Hum NIP. 196101011990012001 NIP. 196509221992031002 v ACKNOWLEDGMENT Praise to Allah SWT Almighty and the most inspiring Prophet Muhammad SAW for the strength and spirit given to the writer so this project on “The Mythological Archetypes and The Living Myth in Alan Garner’s The Owl Service” came to a completion. -

Scratch Pad 59 April 2005

Scratch Pad 59 April 2005 Thank you, fandom! Photo: Bill Burns. Scratch Pad 59 A fanzine based on *brg* 41, for the April 2005 mailing of ANZAPA by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. Email: [email protected]. Weblog: www.appleblossomblues.blogspot.com Contents 2 A LETTER FROM AUSTRALIA 4 ANOTHER CUP OF COFFEE by Bruce Gillespie Bruce Gillespie 5 Previously unpublished Bruce Gillespie article: 4 I HAVE RETURNED! by Bruce Gillespie INNER STARS: THE NOVELS OF ALAN GARNER A letter from Australia Arnie Katz writes in Vegas Weekly Fandom 18: ‘Bruce Gillespie, feted by Vegas Fandom at the Gillespie Gala & Hardin Birthday Bash, sent this letter from the calm and safety of his Australian home.’ Hello, everybody: Garden at the Huntingdon Museum by Marty Cantor, being allowed to touch choice items in the Robert Licht- Thanks to all those who contributed to the BBB Fund man fanzine collection, sampling a good number of and welcomed me to America. But that flight back was America’s restaurant cuisines, and being supported way a horror (14 hours in a plane without an empty seat) and past the call of fannish duty by the great Peter Weston. I was very glad to see Elaine at the gate at Tullamarine It was all Marty Cantor’s fault — or was it Joyce and this morning at 9.30. Arnie Katz’s suggestion in the first place (at the 2004 Impossible to summarise any impressions at the Corflu)? Fannish history is already debating this matter. moment, except that the whole trip was amazing and The kindly presence of Joyce and Arnie hovered over all satisfying to me. -

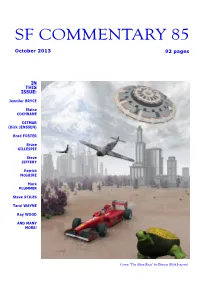

Sf Commentary 85

SF COMMENTARY 85 October 2013 92 pages IN THIS ISSUE: Jennifer BRYCE Elaine COCHRANE DITMAR (Dick JENSSEN) Brad FOSTER Bruce GILLESPIE Steve JEFFERY Patrick McGUIRE Mark PLUMMER Steve STILES Taral WAYNE Ray WOOD AND MANY MORE! Cover: ‘The Alien Race’ by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) SF COMMENTARY 85 October 2013 92 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 85, October 2013, is edited and published in a limited number of print copies by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3068, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. Preferred means of distribution .PDF file from eFanzines.com at: Portrait edition (print equivalent): http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC85P.PDF or Landscape edition (widescreen): http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC85L.PDF or from my email address: [email protected]. Front cover: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘The Alien Race’. Back cover: Steve Stiles: ‘Lovecraft’s Fever Dream’. Artwork Taral Wayne (p. 47); Steve Stiles (p. 52); Brad W. Foster (p. 58). Photographs Peggyann Chevalier (p. 3); Murray and Natalie MacLachlan (p. 4); Helena Binns (p. 26); Barbara Lamar (p. 46); Mervyn and Helena Binns (p. 56); Harold Cazneaux, courtesy Ray Wood (p. 71). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS 45 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (cond.) 4 Friends lost in 2013 4 The Sea and Summer returns Doug Barbour :: Damien Broderick :: Taral Wayne :: John Litchen :: Michael Bishop :: Yvonne Editor Rousseau :: Kaaron Warren :: Tim Marion :: Steve Sneyd :: George Zebrowski :: 5 FAVOURITES 2012 Franz Rottensteiner :: Paul Anderson :: Favourite books of 2012 Sue Bursztynski :: Martin Morse Wooster :: Favourite novels of 2012 Andy Robson :: Jerry Kaufman :: Rick Kennett Favourite short stories of 2012 :: Lloyd Penney :: Joseph Nicholas :: Casey Wolf :: Murray Moore :: Jeff Hamill :: David Lake :: Favourite films of 2012 Pete Young :: Gary Hoff :: Stephen Campbell :: Favourite films re-seen in 2012 John-Henri Holmberg :: David Boutland Television (?!) 2012 (David Rome) :: Matthew Davis :: Favourite filmed music documentaries 2012 William Breiding :: We Also Heard From .. -

{PDF} Strandloper Ebook, Epub

STRANDLOPER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alan Garner | 208 pages | 01 Mar 1999 | Vintage Publishing | 9781860461613 | English | London, United Kingdom Die Strandloper, Langebaan - Menu, Prices & Restaurant Reviews - Tripadvisor After about km from Cape Town city centre, proceed straight past the Engen 1-Stop at the turnoff to Langebaan. After 10 km turn left at the Vredenburg turnoff and continue for 15 km into Paternoster. At the first four-way stop turn right. Continue along the road, driving straight across another four-way stop. Turn left at the second turnoff and then take an immediate right. Carry on straight along the road until you get to the Strandloper Ocean Boutique Hotel. Strandloper Ocean Boutique Hotel partners with the West Coast Kids, a local organization focused on empowering disadvantaged children to find their way out of poverty. Read about our Ghost fishing awareness program and other environmental educational and research on our Blog. Buy Now. In the current pandemic of COVID, a topic that remanins topical, is the impact of human activities on the environment, On a daily basis content from scientific research percolates into public discussion, raising a global focus on awarness of the degradation of marine environments. Plastic pollution has galvanized public focus, initiating mass action to reduce consumption of single use plastics and implement reusable alternatives. Though attention and research is focused on commercial fishing activities, little research has been conducted on the contribution that snagged recreational shoreline fishing tackle makes to ghost fishing. To address the impact of recreational fishing on biodiversity the Strandloper Project is studying ghost fishing and reef damage caused by shore based activities.