Race and (The Study Of) Esotericism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunlite 2 6.Pdf

SUNlite Shedding some light on UFOlogy and UFOs VOICES FROM THE WOODS When we got within a 50 meter distance. The object was producing red and blue light. The blue light was steady and projecting under the object. It was lighting up the area directly under extending a meter or two out. At this point of positive identification I relayed to CSC, SSgt Coffey. Positive sighting of object...colour of lights and that it was definitely mechanical in nature. This is the closest point Penniston relayed that he was close enough to the object to determine that it that I was near the object at any point. We then proceeded after it. It moved in a was definitely a mechanical object. He stated he was within approximately 50 zig-zagging manner back through the woods then lost sight of it. - Jim Penniston meters....Each time Penniston gave me the indication that he was about to reach January 1981 statement the area where the lights were, he would give an extended estimated location. He eventually arrived at a “beacon light”, however, he stated that this was not the light or lights he had originally observed. He was instructed to return. - J. D. Chandler January 1981 statement We climbed over the fence and started heading towards the red and blue lights and they just disappeared. Once we reached the farmer’s house we could see a beacon going around so we went towards it. We followed it for about 2 miles be- fore we could see it was coming from a lighthouse. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Sunlite 2 2.Pdf

SUNlite Shedding some light on UFOlogy and UFOs Seldom has a subject been so invested with fraud, hysteria, cre- dulity, religious mania, incompetence, and most of the other unflattering human characteristics. Arthur C. Clarke Volume 2 Number 2 March-April 2010 Cover: Photograph of a Minuteman III launch from USAF website. Left: Photograph taken by me of Ice Pillars which I saw from my backyard on February 2nd. belief that I would not reveal it. I must have let the comment slip in casual com- munication with Mr. Moseley. It was not done on purpose even though it appears that way. I can only admit my error in revealing this piece of information when I should not have. Speaking of potential hoaxes, it seems that MUFON needs to get their act to- gether. You will see in the “blogging” section that they are dealing with more and more hoaxes. Worse yet is that one of their STAR teams appeared to have let one get by. Somebody caught the red flag but it was not before the UFO Examiner revealed that this case was one of those that remained unexplained after initial investigation. I would hope that these STAR teams would approach such cases skeptically and check for hoax potential. Finally, James Moseley wrote me an inter- Bad Aliens run amok esting note regarding the articles about Stan Romanek. His comment was that he was aware of Romanek being “the One might find the cover a hint at what who say they are abducted. Kitty is very only professional abductee” and that he might be in this issue of SUNlite. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This

Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología ISSN: 1900-5407 Departamento de Antropología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de los Andes Santo, Diana Espírito; Vergara, Alejandra The Possible and the Impossible: Reflections on Evidence in Chilean Ufology* Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología, no. 41, 2020, October-December, pp. 125-146 Departamento de Antropología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de los Andes DOI: https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda41.2020.06 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81464973006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative The Possible and the Impossible: Reflections on Evidence in Chilean Ufology * Diana Espírito Santo** Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Alejandra Vergara*** Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda41.2020.06 How to cite this article: Espírito Santo, Diana and Alejandra Vergara. 2020. “The Possible and the Impossible: Reflections on Evidence in Chilean Ufology.” Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 41: 125-146. https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda41.2020.06 Reception: February 25, 2019; accepted: June 23, 2020; modified: July 31, 2020. Abstract: This article is based on a year of fieldwork with ufologists, contact- 125 ees, abductees, and skeptics in Chile, using methods including ethnography, media and website analysis, and in-depth interviews. Our argument is that the “UFO” serves as, what Galison would call, a theory machine, a multiplic- ity generating not simply heterogeneous interpretive frameworks through which to understand anomalous flying phenomena, in different ideological spheres, but thresholds of evidence as well. -

![The Articulation Between Evolutionism and Creationism in New Religious Movements: Two South American Case Studies[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4261/the-articulation-between-evolutionism-and-creationism-in-new-religious-movements-two-south-american-case-studies-1-1804261.webp)

The Articulation Between Evolutionism and Creationism in New Religious Movements: Two South American Case Studies[1]

Revista del CESLA ISSN: 1641-4713 ISSN: 2081-1160 [email protected] Uniwersytet Warszawski Polonia The articulation between evolutionism and creationism in New Religious Movements: Two South American case studies[1] de Lima Campanha, Vitor The articulation between evolutionism and creationism in New Religious Movements: Two South American case [1] studies Revista del CESLA, vol. 26, 2020 Uniwersytet Warszawski, Polonia Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=243364810005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.36551/2081-1160.2020.26.179-194 PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Debate e articulation between evolutionism and creationism in New Religious Movements: Two South American case studies[1] La articulación entre evolucionismo y creacionismo en los Nuevos Movimientos Religiosos: dos estudios de caso sudamericanos Vitor de Lima Campanha [email protected] Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF), Brasil hp://orcid.org/0000-0002-9546-1859 Abstract: e purpose of this article is to demonstrate how certain religious perspectives Revista del CESLA, vol. 26, 2020 present nuances between the concepts of creation and evolution. Public debate Uniwersytet Warszawski, Polonia characterizes them as polarized concepts. Yet, contemporary religious movements resignify them and create arrangements in which biological evolution and creation Received: 03 March 2020 by the intervention of higher beings are presented in a continuum. It begins with a Accepted: 12 June 2020 brief introduction on the relations and reframing of scientific concepts in the New DOI: https:// Religious Movements and New Age thinking. en we have two case studies which doi.org/10.36551/2081-1160.2020.26.179-194allow us to analyze this evolution-creation synthesis. -

'I've Been Abducted by Aliens'

Cases That Test Your Skills ‘I’ve been abducted by aliens’ Patricia Kinne, MD, and Venna Bhanot, MD Ms. S is afraid to sleep at night because that’s when How would you the aliens come. Is she psychotic, or do her nocturnal handle this case? Visit CurrentPsychiatry.com experiences have another cause? to input your answers and see how your colleagues responded CASE ‘I’m not crazy’ fi culty falling asleep, so I add melatonin, 3 Ms. S, age 55, presents for treatment because to 6 mg at bedtime. Her sleeping pattern she is feeling depressed and anxious. Her is improved, but still variable. She also tries ® symptoms include decreased concentration, Dowdenquetiapine, 25 Healthmg at bedtime, Media but soon dis- intermittent irritability, hoarding, and diffi - continues it due to intolerance. culty starting and completingCopyright tasks. SheFor also personal As our rapport use strengthens, only Ms. S reveals has chronic sleep diffi culties that often keep that she has had multiple encounters with her awake until dawn. aliens beginning at age 3. Although she has Fatigue, lack of focus, and poor compre- not had an “alien experience” for about 5 years, hension and motivation have left her un- she does not feel safe sleeping at night and in- employed. She and her teenage daughter stead sleeps during the day. Her eff orts to stay live with Ms. S’s elderly mother. Ms. S feels awake at night strain her relationship with her tremendous guilt because she cannot be the mother. mother and daughter she wants to be. Initially, I (PK) diagnose Ms. -

Part Ii: Believing That One Has Been Kidnapped by Extraterrestrials

02-Goode-45291.qxd 7/2/2007 12:21 PM Page 33 PART 2 BELIEVING THAT ONE HAS BEEN KIDNAPPED BY EXTRATERRESTRIALS 33 02-Goode-45291.qxd 7/2/2007 12:21 PM Page 34 BEING ABDUCTED BY ALIENS AS A DEVIANT BELIEF An Introduction married man claims to have two children with an alien being.“I know they’re out there, A and they know who I am.”His wife is “confused, angry, and alienated.”All of a sudden, she says,her husband “goes from being a normal guy...to being...well...kind ofnutty, I guess.I don’t believe him,but I don’t disbelieve him either....Would things have been dif- ferent if we’d been able to have kids?”she asks herself.“Basically,I deal with it by trying not to think about it too much”(Clancy, 2005, p. 2). The first widely publicized account of an extraterrestrial kidnapping was reported in the 1960s by Betty and Barney Hill. By the 1990s, a public opinion poll, conducted by the Roper organization, indicated that 3.7 million Americans believe that they have been abducted by space aliens (Hopkins, Jacobs, & Westrum, 1991). In the 1990s, Harvard psychiatrist John Mack (1995) lent academic respectability to such reports by arguing that he believed these claims to be true. The accounts, ranging from the look of the creatures to what they do with abductees, have by now become so standardized as to be eerily predictable. What makes the claim of having been kidnapped by aliens a form of deviance? Mack’s (1995) support of such claims produced stunned incredulity in his colleagues. -

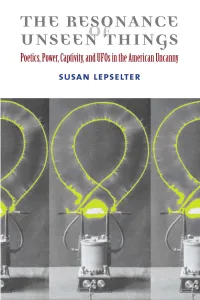

The Resonance of Unseen Things Revised Pages Revised Pages

Revised Pages The Resonance of Unseen Things Revised Pages Revised Pages The Resonance of Unseen Things Poetics, Power, Captivity, and UFOs in the American Uncanny Susan Lepselter University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Susan Lepselter 2016 Published by the University of Michigan Press 2016 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lepselter, Susan Claudia, author. Title: The resonance of unseen things : poetics, power, captivity, and UFOs in the American uncanny / Susan Lepselter. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015043812| ISBN 9780472072941 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472052943 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472121540 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Human-alien encounters. | Conspiracy theories?United States. Classification: LCC BF2050 .L47 2016 | DDC 001.942—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015043812 Revised Pages Acknowledgments This book has morphed in and out of various emergent states for a very long time. It would be impossible to thank everyone who has deepened and expanded my thinking over the years—impossible both because I wish to keep confidential the names of multiple people to whom I am thankful for telling me their own stories, and also because so many people have influenced my ideas in ways too subtle and pervasive to describe. -

Identified Flying Objects: a Multidisciplinary Scientific Approach to the UFO Phenomenon

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Books Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences 2019 Identified Flying Objects: A Multidisciplinary Scientific Approach to the UFO Phenomenon Dr. Michael P. Masters Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/interdisc_arts_sciences_books Part of the Anatomy Commons, Anthropology Commons, and the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons Identified Flying Objects A Multidisciplinary Scientific Approach to the UFO Phenomenon Dr. Michael P. Masters Printed in the United States of America Copyright © 2019 by Dr. Michael P. Masters All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including pho- tocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, with- out the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of fair use involving brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and cer- tain other uses permitted by copyright law. Permission requests should be sent to the author via the contact page at: https://idflyobj.com or in writing at: P.O. Box 461 Butte, MT 59703-0461 Ordering Information: Special discounts are available for quantity purchases. Order requests by U.S. trade bookstores and wholesalers should be sent to the author via the contact page at: https://idflyobj.com or in writing at the above address. Cover Design: Michael Masters Cover Images: Ascent of man ending with smartphone - Frank Fiedler/shutterstock.com; Extratempestrial modified from silhouette of modern human created by Anna Rassadnikova/shutterstock.com; UFO center image by Gl0ck/shutterstock.com First Edition – ISBN: 978-1-7336340-6-9 Printed in the United States of America This book is dedicated to my patient and loving family, friends, sunshine and smiles. -

MORALITY, EPISTEMOLOGY, and ACTIVISM: HOW ANTI- VACCINATION ADVOCATES on TWITTER CONSTRUCT a RHETORIC of ALTERNATIVE IMMUNITY by Mattie Bruton

MORALITY, EPISTEMOLOGY, AND ACTIVISM: HOW ANTI- VACCINATION ADVOCATES ON TWITTER CONSTRUCT A RHETORIC OF ALTERNATIVE IMMUNITY by Mattie Bruton A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English West Lafayette, Indiana August 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Thomas Rickert, Chair Department of English Dr. Patricia Sullivan Department of English Dr. Michael Salvo Department of Communication Dr. Jennifer Bay Department of English Approved by: Dr. Thomas Rickert 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ 4 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 5 PREFACE ....................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION: COMPLICATING “POST-TRUTH” ........................................................... 10 CHAPTER 1: AFFECT, BODY BOUNDARIES, AND EMOTIONAL MORALITIES............ 22 CHAPTER 2: EPISTEMOLOGIES OF CONSPIRACY ............................................................. 42 CHAPTER 2: NETWORKED NARRATIVES AND ACTIVIST IDENITY ............................. 63 CONCLUSION: ALTERNATIVE IMMUNITY IN AN ERA OF PANDEMIC ........................ 82 APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY................................................................................................. -

The Brain & Consciousness

the Skeptical Inquirer $5.00 THE BRAIN & CONSCIOUSNESS — also — Explaining Alien- Abduction Fantasies Past-Life Regression: Misuse of Hypnosis The MJ-12 UFO Documents The Verdict on Creationism Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Vol. XII No. 2 Winter 1987-88 ""Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Public Relations Director Barry Karr. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Systems Programmer Richard Seymour. Art and Layout Kathy Kostek Typesetting Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Ranjit Sandhu. Staff Michael Cione, Crystal Folts, Leland Harrington, Erin O'Hare, Alfreda Pidgeon, Kathy Reeves, Lori Van Amburgh. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher. State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Mark Plummer, Executive Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Eduardo Amaldi, physicist, University of Rome, Italy. Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, University of Minnesota; Brand Blanshard, philoso pher, Yale; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; John R. Cole, anthropologist, Institute for the Study of Human Issues; F. H. -

Extraordinary Encounters: an Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings

EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS An Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings Jerome Clark B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2000 by Jerome Clark All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Jerome. Extraordinary encounters : an encyclopedia of extraterrestrials and otherworldly beings / Jerome Clark. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-249-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 1-57607-379-3 (e-book) 1. Human-alien encounters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF2050.C57 2000 001.942'03—dc21 00-011350 CIP 0605040302010010987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America. To Dakota Dave Hull and John Sherman, for the many years of friendship, laughs, and—always—good music Contents Introduction, xi EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS: AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF EXTRATERRESTRIALS AND OTHERWORLDLY BEINGS A, 1 Angel of the Dark, 22 Abductions by UFOs, 1 Angelucci, Orfeo (1912–1993), 22 Abraham, 7 Anoah, 23 Abram, 7 Anthon, 24 Adama, 7 Antron, 24 Adamski, George (1891–1965), 8 Anunnaki, 24 Aenstrians, 10 Apol, Mr., 25