Money & Mosquitoes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Mechanics of Evolutionary Dynamics

Statistical Mechanics of Evolutionary Dynamics Kumulative Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Christian-Albrechts-Universit¨at zu Kiel vorgelegt von Torsten Rohl¨ Kiel 2007 Referent: Prof. Dr. H. G. Schuster Koreferent(en): Prof. Dr. G. Pfister Tagderm¨undlichenPr¨ufung: 4.Dezember2007 ZumDruckgenehmigt: Kiel,den12.Dezember2007 gez. Prof. Dr. J. Grotemeyer (Dekan) Contents Abstract 1 Kurzfassung 2 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Motivation................................... 3 1.1.1 StatisticalPhysicsandBiologicalSystems . ...... 3 1.1.1.1 Statistical Physics and Evolutionary Dynamics . ... 4 1.1.2 Outline ................................ 7 1.2 GameTheory ................................. 8 1.2.1 ClassicalGameTheory. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 1.2.1.1 TheMatchingPenniesGame . 11 1.2.1.2 ThePrisoner’sDilemmaGame . 13 1.2.2 From Classical Game Theory to Evolutionary Game Theory.... 16 1.3 EvolutionaryDynamics. 18 1.3.1 Introduction.............................. 18 1.3.2 ReplicatorDynamics . 22 1.3.3 GamesinFinitePopulations . 25 1.4 SurveyofthePublications . 29 1.4.1 StochasticGaininPopulationDynamics. ... 29 1.4.2 StochasticGaininFinitePopulations . ... 31 1.4.3 Impact of Fraud on the Mean-Field Dynamics of Cooperative Social Systems................................ 36 2 Publications 41 2.1 Stochasticgaininpopulationdynamics . ..... 42 2.2 Stochasticgaininfinitepopulations . ..... 47 2.3 Impact of fraud on the mean-field dynamics of cooperative socialsystems . 54 Contents II 3 Discussion 63 3.1 ConclusionsandOutlook . 63 Bibliography 67 Curriculum Vitae 78 Selbstandigkeitserkl¨ arung¨ 79 Abstract Evolutionary dynamics is an essential component of a mathematical and computational ap- proach to biology. In recent years the mathematical description of evolution has moved to a description of any kind of process where information is being reproduced in a natural envi- ronment. In this manner everything that lives is a product of evolutionary dynamics. -

Memorandum of Understanding

Memorandum of Understanding between the member universities of the Erasmus Mundus Action 2 consortium „Capacity Building in Higher Education for an improved co-operation between the EU and SA in the field of Development Studies (EUSA_ID)”, Grant Agreement number 2013-2717/001-001 This Memorandum of Understanding is based upon the rules and regulations in place for the participation in the Erasmus Mundus Action 2/Strand 1/Lot 17 project “Capacity Building in Higher Education for an improved co-operation between the EU and SA in the field of Development Studies (EUSA_ID). Provisions contained in the document do not replace or supersede any requirements specified in these rules and regulation. The MoU establishes the terms of the agreement between the partners of the Erasmus Mundus Action2/Strand1/Lot 17 consortium EUSA_ID, defining in detail the principles, objectives, consortium activities, organization and management procedures, and the mobility activities that will be implemented within the framework of this consortium. 1. Principles of the Partnership The consortium universities hereby agree to work together towards the enhancement of the structured co-operation between European and South African Higher Education Institutions, in order to contribute to an academic and cultural exchange in education, research and other areas related to the field of Development Studies. The consortium comprises the following partners: • Ruhr University Bochum (RUB), Institute of Development Research and Development Policy (IEE) – Germany as coordinator -

1 Synth`Ese De La Carri`Ere

CURRICULUM VITAE et listes des travaux et des activit´esde Gilles DURRIEU http://web.univ-ubs.fr/lmam/durrieu/index.html - [email protected] Fran¸cais,mari´e,2 enfants. N´ele : 5 ao^ut1969 `aToulouse 1 Synth`esede la carri`ere Sp´ecialit´es: Statistique non param´etrique,Statistique robuste, Statistique s´equ- entielle, Valeurs extr^emes,Environnement, Biologie et g´en´etique,Statistique appli- qu´eeet Analyse de donn´ees. 35 articles parus ou accept´esdans des revues internationales `acomit´ede lecture (c.f. section A.1) 83 communications dont 26 invit´es dans des conf´erencesnationales et internationales (c.f. section A.3) HDR en Math´ematiques (Universit´ede Bordeaux 1) 23 septembre 2009, mention tr`esho- norable Mod´elisationStatistique de gros volume de donn´eesen environnement et g´en´etique Rapporteurs : Philippe Besse, Alain Pav´eet Fran¸coisSchmitt Jury : Philippe Besse, Alain Boudou, Antoine Gr´emare,Jean-Charles Massabuau, Alain Pav´e et Fran¸cois Schmitt Doctorat en Math´ematiquesAppliqu´ees (Universit´eBordeaux 1) 26 septembre 1997, mention tr`eshonorable Contribution statistique `al'´etudede maladie d'origine mitochondriales Directeurs : Jean-Marc Deshouillers Rapporteurs : Xavier Milhaud et Beno^ıtTruong-Van Jury : Jaromir Antoch, Jean-Marc Deshouillers, Jana Jureˇckov´a, Jean-Pierre Mazat, Xavier Milhaud, Paul Morel, Mikhail Nikouline et Beno^ıtTruong-Van DEA de Math´ematiquesAppliqu´eeset Calculs Scientifiques (Universit´eBordeaux 1) en juin 1994, mention Bien Titulaire de la Prime d'Encadrement Doctoral et de Recherche de septembre 2006 `a septembre 2010 Titulaire de la Prime d'Excellence Scientifique depuis octobre 2012 Poste actuel (depuis septembre 2010): Professeur des Universit´es`al'Universit´ede Bretagne- Sud. -

Notice Personnelle

CURRICULUM VITAE (January 2020)______________________________________________________ Aris DANIILIDIS (Athens, April 15, 1970) Department of Mathematical Engineering & Center of Mathematical Modeling University of Chile (Beauchef 851, Edificio Norte, piso 5, Santiago de Chile) E-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] Web page: http://www.dim.uchile.cl/~arisd/ RESEARCHER ID : I-6737-2013 ORCID PROFILE: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4837-694X RESEARCH GATE: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aris_Daniilidis Languages: English, French, Catalan, Spanish, Greek (written/spoken fluently) PROFESSIONAL SITUATION______________________________________________________________ since 2017 Deputy Director, Centre of Mathematical Modelling DIM-CMM UMI CNRS 2807, University of Chile, Santiago de Chile since 2013 Full Professor (Profesor Titular), Department of Mathematical Engineering DIM-CMM UMI CNRS 2807, University of Chile, Santiago de Chile 2007— 2013 Tenure Associate Professor (Professor Agregat) (on leave), Department of Mathematics, University Autonomous of Barcelona, SPAIN 2004— 2007 Tenure-track researcher (investigador Ramon y Cajal), Department of Mathematics University Autonomous of Barcelona, SPAIN Autumn 2003 Post-doctorate researcher, INRIA, Rhône-Alpes, FRANCE BIBOP Team (Non-regular Mechanics) 2002—2003 Post-doctorate researcher, Department of Economics University Autonomous of Barcelona, SPAIN 2001—2002 Post-doctorate researcher, INRIA, Rhône-Alpes, FRANCE NUMOP Team (Numerical Optimization) 2000—2001 Teaching Assistant (ATER), -

The Interface Theory of Perception

!1 The Interface Theory of Perception (To appear in The Stevens' Handbook of Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience) DONALD D. HOFFMAN ABSTRACT Our perceptual capacities are products of evolution and have been shaped by natural selection. It is often assumed that natural selection favors veridical perceptions, namely, perceptions that accurately describe those aspects of the environment that are crucial to survival and reproductive fitness. However, analysis of perceptual evolution using evolutionary game theory reveals that veridical perceptions are generically driven to extinction by equally complex non-veridical perceptions that are tuned to the relevant fitness functions. Veridical perceptions are not, in general, favored by natural selection. This result requires a comprehensive reframing of perceptual theory, including new accounts of illusions and hallucinations. This is the intent of the interface theory of perception, which proposes that our perceptions have been shaped by natural selection to hide objective reality and instead to give us species-specific symbols that guide adaptive behavior in our niche. INTRODUCTION Our biological organs — such as our hearts, livers, and bones — are products of evolution. So too are our perceptual capacities — our ability to see an apple, smell an orange, touch a grapefruit, taste a carrot and hear it crunch when we take a bite. Perceptual scientists take this for granted. But it turns out to be a nontrivial fact with surprising consequences for our understanding of perception. The -

Classement CNRS Des Revues En Économie Et Gestion

Should you believe in the Shanghai ranking? Denis Bouyssou, CNRS, LAMSADE, Paris, France (joint work with J.-Ch. Billaut and Ph. Vincke) Liège, November 2009 Media OutlineOutlineOutline Outline Academic Ranking of World Universities 2009 Details of ranking methodology Some naïve comments Some comments inspired from MCDM Conclusions OutlineOutlineOutline Outline Academic Ranking of World Universities 2009 Details of ranking methodology Some naïve comments Some comments inspired from MCDM Conclusions Shanghai Ranking Jiao Tong University, Shanghai Institute of Higher Education Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) 500 universities worldwide ranked annually since 2003 (2009 is the 7th edition) http://www.arwu.org/ranking.htm Top 20 World (2009) Rank Institution Country Alumni Award HiCI N&S PUB PROD Score 1 Harvard University USA 100 100 100 100 100 74,8 100 2 Stanford University USA 39 78,7 87,1 67,3 70,1 66,9 73,1 3 University of California, Berkeley USA 67,4 77,1 68,4 71,1 69 53,2 71 4 University of Cambridge UK 89,4 91,5 53,8 53,9 65,4 65,5 70,2 5 MIT USA 71 80,6 65,7 67,9 62 54,4 69,5 6 California Institute of Technology USA 51,5 69,1 57,1 66,2 47,7 100 64,8 7 Columbia University USA 70,6 67,7 55,7 49,1 69,6 46,5 61,7 8 Princeton University USA 57,8 85,2 61,6 41,5 45,7 61,4 60,2 9 University of Chicago USA 65,8 84,3 49,7 38,6 51,6 41,8 57 10 University of Oxford UK 57,6 57,9 48,9 49,8 66,1 45,7 56,3 11 Yale University USA 49,8 43,6 57,6 55,7 62,7 49,5 55,2 12 Cornell University USA 40,5 51,3 54,3 51,7 61,2 39,9 -

1 Appendix 6: Comparison of Year Abroad Partnerships with Our

Appendix 6: Comparison of year abroad partnerships with our national competitors Imperial College London’s current year abroad exchange links (data provided by Registry and reflects official exchange links for 2012-131) and their top 5 competitors’ (based on UCAS application data) exchange links are shown below. The data for competitors was confirmed either by a member of university staff (green) or obtained from their website (orange). Data was supplied/obtained between August and October 2012. Aeronautics Imperial College London France: École Centrale de Lyon, ENSICA – SupAero Germany: RWTH Aachen Singapore: National University of Singapore USA: University of California (Education Abroad Program) University of Cambridge France: École Centrale Paris Germany: Tech. University of Munich Singapore: National University of Singapore USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Oxford USA: Princeton University of Bristol Australia: University of Sydney Europe University of Southampton France: ESTACA, ENSICA – SupAero, DTUS – École Navale Brest Germany: University of Stuttgart Spain: Polytechnic University of Madrid Sweden: KTH University of Manchester Couldn’t find any evidence Bioengineering Imperial College London Australia: University of Melbourne France: Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble Netherlands: TU Delft Singapore: National University of Singapore Switzerland: ETH Zurich USA: University of California (Education Abroad Program) University of Cambridge France: École Centrale Paris Germany: Tech. University of Munich -

Lis Full CV 2021.Pages

Curriculum Vitae Dariusz C. (Darek) Lis Educa7on 1985 – 1989 University of MassachuseEs, Amherst, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Ph. D. 1981 – 1985 University of Warsaw, Department of Physics. Professional Experience 1989 – California Ins7tute of Technology. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Scien7st 2019 –. Research Fellow in Physics 1989 – 1992; Senior Research Fellow in Physics (Research Assistant Professor) 1992 – 1998; Senior Research Associate in Physics (Research Professor) 1998 – 2015; Deputy Director, Caltech Submillimeter Observatory 2009 – 2014; Visi7ng Associate in Physics 2015 – 2020. 2014 – 2019 Sorbonne University (Pierre and Marie Curie University), Paris Observatory (PSL University). Professor (Professeur des universités 1ère classe); Director, Laboratory for Studies of Radia7on and MaEer in Astrophysics and Atmospheres (UMR 8112). 1985 – 1989 University of MassachuseEs. Research Assistant, Five College Radio Astronomy Observatory. Visi7ng Appointments 2013 École normale supérieure. Visi7ng Professor (Professeur des universités 1ère classe invité). 2011 University of Bordeaux 1. Visi7ng Associate Professor (Maître de conférences invité). 2007 Paris Observatory. Visi7ng Senior Astronomer (Astronome invité). 2003 Max Planck Ins7tute for Radio Astronomy. Visi7ng Scien7st. 1992 – 1994 University of California, Los Angeles. Lecturer. Awards 2014 NASA Group Achievement Award, U.S. Herschel HIFI Instrument Team. 2010 NASA Group Achievement Award, Herschel HIFI Hardware Development Team. 1985 Minister of Science and Higher Learning Fellowship, Poland. Research Astrophysics and astrochemistry of the interstellar medium, star forma7on. Evolu7on of molecular complexity in astrophysical environments. Vola7le composi7on of comets and the origin of Earth’s oceans. Submillimeter heterodyne instrumenta7on. Cometary research featured on Na7onal Geographic, CBC Quirks & Quarks, and in Scien7fic American. Astrophysics Data System: 254 refereed publica7ons, 11,500 cita7ons. Books edited: Submillimeter Astrophysics and Technology: A Symposium Honoring Thomas G. -

Final Program

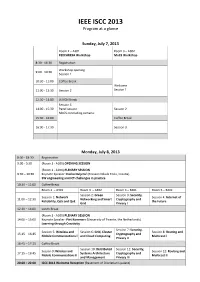

IEEE ISCC 2013 Program at a glance Sunday, July 7, 2013 Room 2 – A301 Room 3 – A302 PEDISWESA Workshop MoCS Workshop 8:30 ‐ 16:30 Registration Workshop opening 9:00 ‐ 10:30 Session 1 10:30 ‐ 11:00 Coffee Break Welcome 11:00 ‐ 12:30 Session 2 Session 1 12:30 ‐ 14:00 LUNCH Break Session 3 14:00 ‐ 15:30 Panel session Session 2 MoCS concluding remarks 15:30 ‐ 16:00 Coffee Break 16:00 ‐ 17:30 Session 3 Monday, July 8, 2013 8:00 ‐ 18:30 Registration 9:00 ‐ 9:30 (Room 1 ‐ A100) OPENING SESSION (Room 1 ‐ A100) PLENARY SESSION 9:30 – 10:30 Keynote Speaker: Darko Huljenić (Ericsson Nikola Tesla, Croatia) SW engineering and ICT challenges in practice 10:30 – 11:00 Coffee Break Room 2 – A301 Room 3 – A302 Room 4 – B401 Room 5 – B402 Session 2: Green Session 3: Security, Session 1: Network Session 4: Internet of 11:00 – 12:30 Networking and Smart Cryptography and Reliability, QoS and QoE the Future Grid Privacy I 12:30 – 14:00 Lunch Break (Room 1 ‐ A100) PLENARY SESSION 14:00 – 15:00 Keynote Speaker: Piet Kommers (University of Twente, the Netherlands) Learning through Creativity Session 7: Security, Session 5: Wireless and Session 6: Grid, Cluster Session 8: Routing and 15:15 – 16:45 Cryptography and Mobile Communications I and Cloud Computing Multicast I Privacy II 16:45 – 17:15 Coffee Break Session 10: Distributed Session 11: Security, Session 9: Wireless and Session 12: Routing and 17:15 – 18:45 Systems Architecture Cryptography and Mobile Communications II Multicast II and Management Privacy III 20:00 – 22:00 ISCC 2013 Welcome Reception (Basement -

Money & Mosquitoes

MONEY & MOSQUITOES THE ECONOMICS OF MALARIA IN AN AGE OF DECLINING AID AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK POLICY RESEARCH DOCUMENT 1 Eric Maskin Harvard University Célestin Monga African Development Bank Josselin Thuilliez Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Jean-Claude Berthélemy University of Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne Eric Maskin is the Adams University Professor at Harvard University. He has made contributions to game theory, contract theory, social choice theory, political economy, and other areas of economics. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics (with Leonid Hurwicz and Roger Myerson) for laying the foun- dations of mechanism design theory. After a postdoctoral fellowship at Cambridge University, he was a faculty member at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard, and the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton before rejoining the Harvard faculty in 2012. Célestin Monga is Vice President for Economic Governance and Knowledge Management at the African Development Bank (AfDB) Group. He previously served as Managing Director at the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, and Senior Advisor/Director for Structural Transformation at the World Bank. He has held various board and senior positions in academia and financial services, includ- ing as a pro bono member of the advisory boards at MIT's Sloan School of Management, and Visiting Professor of Economics at Boston University, the University of Bordeaux 1, the University of Paris 1-Pan- théon-Sorbonne, and Peking University. Josselin Thuilliez is Research Professor at the French national center for scientific research (CNRS) based at the Centre d'Economie de la Sorbonne (a joint research unit between CNRS and the University of Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne). -

Sûreté De Fonctionnement

Module de s^uret´ede fonctionnement Claire Pagetti - ENSEEIHT 3`eme TR - option SE 10 d´ecembre 2012 Table des mati`eres 1 Principaux concepts3 1.1 Qu'est-ce que la s^uret´ede fonctionnement......................3 1.1.1 Bref historique.................................4 1.1.2 Co^utde la s^uret´ede fonctionnement.....................4 1.2 Etude des syst`emes...................................5 1.3 Taxonomie.......................................7 1.3.1 Entraves.....................................8 1.3.2 Attributs.................................... 11 1.3.3 Les moyens................................... 12 1.4 Conception de syst`emes`ahaut niveau de s^uret´ede fonctionnement........ 13 2 M´ethodes d'analyse de s^uret´ede fonctionnement 13 2.1 Analyse pr´eliminairedes dangers........................... 14 2.2 AMDE.......................................... 15 2.3 Diagramme de fiabilit´e................................. 17 2.4 M´ethodes quantitatives et qualitatives........................ 18 2.4.1 Evaluation qualitative............................. 18 2.4.2 Evaluation quantitative............................ 18 2.4.3 Syst`ememulticomposants........................... 22 2.5 TP sur les diagrammes de fiabilit´e.......................... 25 3 Arbres de d´efaillances 26 3.1 Construction d'un arbre de d´efaillance........................ 26 3.2 TP arbres de d´efaillance................................ 30 3.3 Codage des arbres de d´efaillancesous forme de DDB................ 32 4 Mod`eles`a´etatstransitions 34 4.1 Cha^ınesde Markov................................... 34 4.1.1 Construction d'un mod`ele........................... 36 4.2 Evaluation de la fiabilit´e,de la disponibilit´eet du MTTF............. 39 4.3 R´eseauxde Petri stochastiques............................ 41 4.3.1 Mod´elisationdes syst`emesavec des r´eseauxde Petri............ 41 4.4 AltaRica......................................... 44 4.4.1 Mod´elisationdes syst`emeavec AltaRica.................. -

Beyond Competition in Evolution and Social Learning Communities

Beyond Competition in Evolution and Social Learning communities. Jordan Pollack Brandeis University DEMO.CS.BRANDEIS.EDU EUCognition January 2008 My Lab’s Research ! How do biological systems progress without a designer? ! Can we understand open- ended evolution in enough formal detail to replicate the process using computer technology? ! What are beneficial applications? Demo.cs.brandeis.edu 1 Co-Evolution as Arms-race ! In Nature, Co-evolution means contingent development between species. ! But in Machine Learning the goal is an unstoppable “arms race” towards complexity. Demo.cs.brandeis.edu Canonical Coev. Algorithm Initialize random “genotypes” Pop. Evaluate Members Fitness computed By complete mixing y Output Done? Fittest Individuals n Select Parents New Generation Generate/Insert Offspring Demo.cs.brandeis.edu 2 Open-ended Evolution as Learning by Playing a game Detects Invents “tells” The Bluff (signals) Learns Knows probabilities what to draw Demo.cs.brandeis.edu Co-evolutionary Success Stories ! Prisoner Dilemma (Axelrod & Forrest) ! Pursuer Evader (Cliff, Reynolds …) ! Sorting Nets (Hillis, Juille) ! Game Players (Rosin, Angeline, Tesauro, Blair, Fogel) ! Cell Automata Rules (Packard, Juille) ! Robotics (Sims, Floreano, Funes, Lipson, Hornby) ! Education Technology (Sklar, Bader-Natal) (My students) Demo.cs.brandeis.edu 3 Coevolutionary Robots Evolutionary Computing Virtual Reality Simulation Artificial Lifeforms Demo.cs.brandeis.edu Can we turn Virtual Creatures Real? 3d Printing Machine 1999=$50,000 2009= $5000 CNC, CIM,