A Case of Severe Birth Defects Possibly Due to Cursing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT the Women of Supernatural: More Than

ABSTRACT The Women of Supernatural: More than Stereotypes Miranda B. Leddy, M.A. Mentor: Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. This critical discourse analysis of the American horror television show, Supernatural, uses a gender perspective to assess the stereotypes and female characters in the popular series. As part of this study 34 episodes of Supernatural and 19 female characters were analyzed. Findings indicate that while the target audience for Supernatural is women, the show tends to portray them in traditional, feminine, and horror genre stereotypes. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: 1) to provide a description of the types of female characters prevalent in the early seasons of Supernatural including mother-figures, victims, and monsters, and 2) to describe the changes that take place in the later seasons when the female characters no longer fit into feminine or horror stereotypes. Findings indicate that female characters of Supernatural have evolved throughout the seasons of the show and are more than just background characters in need of rescue. These findings are important because they illustrate that representations of women in television are not always based on stereotypes, and that the horror genre is evolving and beginning to depict strong female characters that are brave, intellectual leaders instead of victims being rescued by men. The female audience will be exposed to a more accurate portrayal of women to which they can relate and be inspired. Copyright © 2014 by Miranda B. Leddy All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Tables -

Child Sacrifice: Myth Or Reality?

International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Online: 2014-09-30 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 41, pp 1-11 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.41.1 2014 SciPress Ltd, Switzerland Child Sacrifice: myth or reality? Paul Bukuluki Department of Social Work and Social Administration, School of Social Sciences, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT The paper makes an effort to define, contextualise and present cases of child sacrifice and some of its drivers. It argues that child mutilation and sacrifice is not a myth but rather an emerging unfortunate reality in some communities in Uganda and other parts of Africa. The paper also presents the historical overview, theoretical, policy and programming implications of the phenomenon of child mutilation and sacrifice. Keywords: Sacrifice; mutilation; child protection; theoretical and programming issues 1. INTRODUCTION “How is it possible that ordinary people kill someone in cold blood and as if it wasn’t enough, they remove things from the body as if they were removing giblets from a chicken” (sister of victim, whose genital organs were removed, cited in Fellows, 2010: 1) Child protection as a concept and practice has gained a lot of attention and importance in the last two decades. It is reflected both in the United Nations Convention for the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Many countries all over the world including those in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have made significant strides towards domestication of the UNCRC and MDGs through enactment of policies, programmes and services that foster child protection. -

Supernatural' Fandom As a Religion

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion Hannah Grobisen Claremont McKenna College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grobisen, Hannah, "The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2010. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2010 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College The Winchester Gospel The Supernatural Fandom as a Religion submitted to Professor Elizabeth Affuso and Professor Thomas Connelly by Hannah Grobisen for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 December 10, 2018 Table of Contents Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family………………………………………………………1 Saving People, Hunting Things. The Family Business: Messages, Values and Character Relationships that Foster a Community……………………………………………........9 There is No Singing in Supernatural: Fanfic, Fan Art and Fan Interpretation….......... 20 Gay Love Can Pierce Through the Veil of Death: The Importance of Slash Fiction….25 There’s Nothing More Dangerous than Some A-hole Who Thinks He’s on a Holy Mission: Toxic Misrepresentations of Fandom……………………………………......34 This is the End of All Things: Final Thoughts………………………………………...38 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………39 Important Characters List……………………………………………………………...41 Popular Ships…………………………………………………………………………..44 1 Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family Supernatural (WB/CW Network, 2005-) is the longest running continuous science fiction television show in America. -

What Is the Source of Everything? Ontology

SBCW 2018 Markus Reichenbach What is the source of everything? Ontology by Markus Reichenbach 2018 Introduction to a Biblical Christian Worldview Seite 1 SBCW 2018 Markus Reichenbach Content 1 Question 1: What is the ultimate source of everything? 2 2 Question 2: How did God create the world? 4 2.1 What does the bible says (Gen 1:1-25) 4 2.2 How old is the earth? 5 2.2.1 What does the bible say? 6 3 Question 3: How does live came into existence? 7 3.1 Macro- and Microevolution 8 3.2 Evolution theory destroys Christianity 8 4 Conclusion 10 1 Question 1: What is the ultimate source of eve- rything? What is the ultimate source of everything? Where did God come from? Probably you have already asked yourself these questions. Is there an answer? How can we be certain about the ultimate source of everything? Perhaps, the best way to find an answer is to look at all the possibilities and find out what the best logical answer would be. Before the middle of last century, scientists believed that amino acids and gases ex- ploded in the Big Bang and that the first cell evolved. They claimed that matter had always been there in the form of energy or gases. To them, matter was eternal and the source of everything. If matter were the ultimate source of everything then what is man? Is he not more than a piece of dirt somewhere in the universe? He just come from dust and turns back into dust in those millions of years? Insignificant, unimportant, not seen by anyone, from dust to dust, lost somewhere in a galaxy. -

The “Problem” of Male Friendship in Supernatural and Its Fan Fiction

Praxes of popular culture No. 1 - Year 9 12/2018 - LC.4 [sic] - a journal of literature, culture and literary translation Melodie Cardin, Carleton University, Canada ([email protected]) The “Problem” of Male Friendship in Supernatural and Its Fan Fiction Abstract This article considers the inclusion of the real-life “slash” fandom in the canon storyline of the CW/WB show Supernatural , and the consequent exploration of the taboo idea raised by the fans: of a sexual relationship between its two central characters, who are brothers. By including references to fan fiction, Supernatural opens a space to question normative sexual identity constructs. This article draws on an argument by Michel Foucault that homosexuality is a social construct that emerged as a way to deal with the “problem of male friendship.” In the context of Foucault’s argument, Supernatural ’s treatment of its “slash” fan fiction allows for polysemic interpretations of the brothers’ relationship to coexist with the platonic “canon” storyline, opening the door to ideas of sexual fluidity and the “queering” of its characters by fans. Keywords : fan fiction, sexual identity, Foucault, intimatopias, Supernatural Introduction Supernatural is an American primetime show centered on a monster-of-the-week mystery format, led by the fictional brothers Sam and Dean Winchester (played by Jared Padalecki and Jensen Ackles), hunters of supernatural phenomena. In the fourth season, the brothers are in the midst of their usual investigation when they discover a book series that tells their own life story. As they begin to investigate this odd phenomenon, they discover that this book series has fans . -

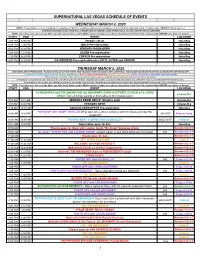

Supernatural Las Vegas Schedule of Events

SUPERNATURAL LAS VEGAS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS WEDNESDAY MARCH 4, 2020 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS will be open too! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, SILVER, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. NOTE: If you have solo, duo or group photo ops with Jared, Jensen, and/or Misha, please exchange your pdf for a hard ticket at the Photo Op exchange table BEFORE your photo op begins! START END EVENT LOCATION 2:00 PM 6:00 PM Vendors set-up Salsa Reg 6:00 PM 7:00 PM GOLD Pre-registration Salsa Reg 6:00 PM 8:30 PM VENDORS ROOM OPEN Salsa Reg 7:00 PM 7:10 PM SILVER Pre-registration Salsa Reg 7:10 PM 8:00 PM COPPER Pre-registration Salsa Reg 8:00 PM 8:30 PM GA WEEKEND Pre-registration plus GOLD, SILVER and COPPER Salsa Reg THURSDAY MARCH 5, 2020 *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. PLEASE SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE MISSED AUTOGRAPHS OR PHOTO OPS. Light Blue: Private meet & greets, Green: Autographs, Red: Theatre programming, Orange: VIP schedule, Purple: Photo ops, Dark Blue: Special Events Photo ops are on a first come, first served basis (unless you're a VIP or unless otherwise noted in the Photo op listing) Autographs for Gold/Silver are called row by row, then by those with their separate autographs, pre-purchased autographs are called first. -

No More Mr. Nice Angel

Digital Collections @ Dordt Faculty Work Comprehensive List 2016 No More Mr. Nice Angel Scott Culpepper Dordt College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Culpepper, S. (2016). No More Mr. Nice Angel. The Supernatural Revamped Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work/878 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Work Comprehensive List by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No More Mr. Nice Angel Abstract Angels have occupied a prominent role in world religions and Western culture for centuries. The existence of multiple supernatural beings with varying degrees of hierarchical standing was a given for the polytheistic cultures that represented the majority of religious expressions in the ancient world. The inclusion of these supernatural beings in the three great monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam was significant because these faiths sought in ve ery way to emphasize the supremacy of the one God in contrast to the crowded spiritual field of polytheistic faiths. Angels could be problematic because they potentially provided a host of supernatural entities competing alongside the one God. Keywords angels, supernatural, legends, Paradise Lost, demonology Disciplines Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity | Christianity Comments Chapter from edited book: https://dordt.on.worldcat.org//oclc/934746463 Culpepper, Scott. "No More Mr. -

Ritual Killing in Ancient Rome: Homicide and Roman Superiority Dawn F Carver, Jasmine Watson, Jason Curtiss Jr

EL RIO: A STUDENT RESEARCH JOURNAL HUMANITIES Ritual Killing in Ancient Rome: Homicide and Roman Superiority Dawn F Carver, Jasmine Watson, Jason Curtiss Jr. Colorado State University-Pueblo ABSTRACT The ancient Romans outlawed human sacrifice in 97 BCE after increasing discomfort with the practice, but ritual killing still occurred because it was justified in a way that preserved Roman superiority. The ancient Romans interpreted the favor of the gods as justification to perform ritual killings. This paper explains the difference between human sacrifice and ritual killing using a wide collection of primary source documents to explain how the Romans felt that their supe- riority depended on the continued practice of ritual killing. The ancient Romans had to differ- entiate between ritual killings and human sacrifice to maintain their superiority over other soci- eties, but to maintain the favor of the many Roman gods, they needed to perform ritual killings. CC-BY Dawn F Carver, Jasmine Watson, Jason Curtiss Jr. Published by the Colorado State University Library, Pueb- lo, CO, 81001. 3 SPRING 2018 Aelia was exhausted, she had been in labor all night and into the following day, but the baby would not come. She was worried, she had heard the slaves talking about two wolves that had come into Rome last night right around the time her pains had started. Such a bad omen, her baby must be alright, but the signs were worrisome. There is a commotion outside, people are shouting. What are they saying about the sun? Oh no, the baby is coming! Where is the midwife? She is still outside; please come back! Moments later, a baby’s wail breaks through to the midwife who rushes back in to find that Aelia has had her baby. -

Child Sacrifice in Uganda

CHILD SACRIFICE IN UGANDA Allan Ssembatya is known as a ‘miracle child’ after he survived a ritual sacrifice on 19th October 2009, aged 7 years old. Allan’s father, Hudson Kizza Ssemwanga, sold their house to pay for Allan’s medical expenses and left his job in order to care for his son. Report by Jubilee Campaign and Kyampisi Childcare Ministries Child Sacrifice in Uganda A report by Jubilee Campaign and Kyampisi Childcare Ministries © 2011 Jubilee Campaign and Kyampisi Childcare Ministries 1 Child Sacrifice in Uganda A report by Jubilee Campaign and Kyampisi Childcare Ministries Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................... p.3 2. Case Studies .................................................................................. p.5 3. Report of Cases of Abduction and Sacrifice from 1998 ................... p.14 4. Update on Registered Cases July 2006 – March 2011 ................... p.21 5. Background and Context ................................................................ p.35 6. Why is Child Sacrifice undertaken? ................................................ p.37 7. Process .......................................................................................... p.40 8. Causes ........................................................................................... p.42 9. Effects ............................................................................................ p.46 10. Perpetrators.................................................................................. -

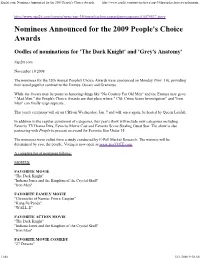

Zap2it.Com: Nominees Announ

Zap2it.com: Nominees Announced for the 2009 People's Choice Awards http://www.zap2it.com/movies/news/zap-35thpeopleschoiceawardsnomin... http://www.zap2it.com/movies/news/zap-35thpeopleschoiceawardsnominations,0,5074537.story Nominees Announced for the 2009 People's Choice Awards Oodles of nominations for 'The Dark Knight' and 'Grey's Anatomy' Zap2It.com November 10 2008 The nominees for the 35th Annual People's Choice Awards were announced on Monday (Nov. 10), providing their usual populist contrast to the Emmys, Oscars and Grammys. While the Oscars may be prone to honoring things like "No Country For Old Men" and the Emmys may go to " Mad Men," the People's Choice Awards are that place where " CSI: Crime Scene Investigation" and "Iron Man" can finally reign supreme. This year's ceremony will air on CBS on Wednesday, Jan. 7 and will, once again, be hosted by Queen Latifah. In addition to the regular assortment of categories, this year's show will include new categories including Favorite TV Drama Diva, Favorite Movie Cast and Favorite Scene Stealing Guest Star. The show is also partnering with People to present an award for Favorite Star Under 35. The nominees were culled from a study conducted by E-Poll Market Research. The winners will be determined by you, the people. Voting is now open as www.pcaVOTE.com. A complete list of nominees follows: MOVIES: FAVORITE MOVIE "The Dark Knight" "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" "Iron Man" FAVORITE FAMILY MOVIE "Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian" "Kung Fu Panda" "WALL-E" FAVORITE ACTION MOVIE "The Dark Knight" "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" "Iron Man" FAVORITE MOVIE COMEDY "27 Dresses" 1 of 6 12/1/2008 9:50 AM Zap2it.com: Nominees Announced for the 2009 People's Choice Awards http://www.zap2it.com/movies/news/zap-35thpeopleschoiceawardsnomin.. -

Hello. Sid Roth Here. Welcome to My World Where It's Naturally Supernatural

Hello. Sid Roth here. Welcome to my world where it's naturally supernatural. My guest prayed for a baby, now get this, that was dead for one year. And the baby came back to life. You won't believe what happened next. Sid Roth spent over 40 years researching the strange world of the supernatural. Join Sid for this edition of It's Supernatural! SID: Yes. You heard me right. A baby that had been dead for a year comes back to life? What are you talking about, James? JAMES: It was amazing, man. It was a few years ago now. It was 2000, I believe in '12. It was unbelievable. We went on a missions trip to Ghana. We were doing crusades at night, and we were going in the villages in the day. And this one morning I woke up. As soon as I sat up in my bed, I just felt this fire surging through my body. And I actually went to the people that came on the trip, and I said, "Look, we're all going into villages today, asking for the sickest person we could find to just believe that God would heal him." I took a couple of pastors from the church there in Ghana with me. We went up about the new— SID: Now, this was a big church. JAMES: Yeah. Royalhouse Chapel, huge church in Ghana, West Africa. And I asked the pastor with me, "Can you take me to the hardest area?" Everybody wants to run from... I'm like bring it on. -

Polymediated Narrative: the Case of the Supernatural Episode “Fan Fiction”

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 748–765 1932–8036/20160005 Polymediated Narrative: The Case of the Supernatural Episode “Fan Fiction” ART HERBIG Indiana University–Purdue University Fort Wayne, USA ANDREW F. HERRMANN East Tennessee State University, USA Modern stories are the product of a recursive process influenced by elements of genre, outside content, medium, and more. These stories exist in a multitude of forms and are transmitted across multiple media. This article examines how those stories function as pieces of a broader narrative, as well as how that narrative acts as a world for the creation of stories. Through an examination of the polymediated nature of modern narratives, we explore the complicated nature of modern storytelling. Keywords: polymedia, narrative, rhetoric, fandom, television, story, convergence, transmedia, Supernatural, serialization, storytelling, mythology, popular, media, technology, audience, showrunner, discourse, myth, culture Whether one starts with the storyteller or the audience, or with ancient mythologies or new narratives, examining and working through stories is more art than science. Particularly in this media age, the definitions of terms such as content, consumption, and authorship are changing (Tyma, Herrmann, & Herbig, 2015). For instance, audiences are no longer assumed to be passive consumers of media. Academics, producers, and advertisers alike attempt to account for the ways they are blogging, Tweeting during broadcasts, Facebooking spoilers, writing fan/slash fiction, or being involved with participatory television talk shows dedicated to one particular series. These people are active participants, both consumers and producers simultaneously. On the other side, the producers, directors, and writers, traditionally thought of as the authors of our public texts, are now forced to interact and react to their audiences in ways that position them as much as interpreter as creator (McGee, 1990).