Provided by the Author(S) and University College Dublin Library in Accordance with Publisher Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

Sunday Independent

gjj Dan O'Brien The Irish are becoming EXCLUSIVE ‘I was hoping he’d die,’ Jill / ungovernable. This Section, Page 18Meagher’s husband on her murderer. Page 20 9 6 2 ,0 0 0 READERS Vol. 109 No. 17 CITY FINAL April 27,2014 €2.90 (£1.50 in Northern Ireland) lMELDA¥ 1 1 P 1 g§%g k ■MAY ■ H l f PRINCE PHILIP WAS CHECKING OUT MY ASS LIFE MAGAZINE ALL IS CHANGING, CHANGING UTTERLY. GRAINNE'SJOY ■ Voters w a n t a n ew political p arty Poll: FG gets MICHAEL McDOWELL, Page 24 ■ Public demands more powers for PAC SHANE ROSS, Page 24 it in the neck; ■ Ireland wants Universal Health Insurance -but doesn'tbelieve the Governmentcan deliver BRENDAN O'CONNOR, Page 25 ■ We are deeply suspicious SF rampant; of thecharity sector MAEVE SHEEHAN, Page 25 ■ Royal family are welcome to 1916 celebrations EILISH O'HANLON, Page 25 new partycall LOVE IS IN THE AIR: TV presenter Grainne Seoige and former ■ ie s s a Childers is rugbycoach turned businessman Leon Jordaan celebrating iittn of the capital their engagement yesterday. Grainne's dress is from Havana EOGHAN HARRIS, Page 19 in Donnybrookr Dublin 4. Photo: Gerry Mooney. Hayesfaces defeat in Dublin; Nessa to top Full Story, Page 5 & Living, Page 2 poll; SF set to take seat in each constituency da n ie l Mc Connell former minister Eamon Ryan and JOHN DRENNAN (11 per cent). MillwardBrown Our poll also asked for peo FINE Gael Junior Minister ple’s second preference in Brian Hayes is facing a humil FULL POLL DETAILS AND ANALYSIS: ‘ terms of candidate. -

Irish Political Review, January, 2011

Of Morality & Corruption Ireland & Israel Another PD Budget! Brendan Clifford Philip O'Connor Labour Comment page 16 page 23 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW January 2011 Vol.26, No.1 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.25 No.1 ISSN 954-5891 Economic Mindgames Irish Budget 2011 To Default or Not to Default? that is the question facing the Irish democracy at present. In normal circumstances this would be Should Ireland become the first Euro-zone country to renege on its debts? The bank debt considered an awful budget. But the cir- in question has largely been incurred by private institutions of the capitalist system, cumstances are not normal. Our current which. made plenty money for themselves when times were good—which adds a budget deficit has ballooned to 11.6% of piquancy to the choice ahead. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) excluding As Irish Congress of Trade Unions General Secretary David Begg has pointed out, the bank debt (over 30% when the once-off Banks have been reckless. The net foreign debt of the Irish banking sector was 10% of bank recapitalisation is taken into account). Gross Domestic Product in 2003. By 2008 it had risen to 60%. And he adds: "They lied Our State debt to GDP is set to increase to about their exposure" (Irish Times, 13.12.10). just over 100% in the coming years. A few When the world financial crisis sapped investor confidence, and cut off the supply of years ago our State debt was one of the funds to banks across the world, the Irish banks threatened to become insolvent as private lowest, but now it is one of the highest, institutions. -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Papers of Gemma Hussey P179 Ucd Archives

PAPERS OF GEMMA HUSSEY P179 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 © 2016 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History vi CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vii System of Arrangement ix CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access xi Language xi Finding Aid xi DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note xi ALLIED MATERIALS Allied Collections in UCD Archives xi Published Material xi iii CONTEXT Biographical History Gemma Hussey nee Moran was born on 11 November 1938. She grew up in Bray, Co. Wicklow and was educated at the local Loreto school and by the Sacred Heart nuns in Mount Anville, Goatstown, Co. Dublin. She obtained an arts degree from University College Dublin and went on to run a successful language school along with her business partner Maureen Concannon from 1963 to 1974. She is married to Dermot (Derry) Hussey and has one son and two daughters. Gemma Hussey has a strong interest in arts and culture and in 1974 she was appointed to the board of the Abbey Theatre serving as a director until 1978. As a director Gemma Hussey was involved in the development of policy for the theatre as well as attending performances and reviewing scripts submitted by playwrights. In 1977 she became one of the directors of TEAM, (the Irish Theatre in Education Group) an initiative that emerged from the Young Abbey in September 1975 and founded by Joe Dowling. It was aimed at bringing theatre and theatre performance into the lives of children and young adults. -

Regional Hub Sustainability Building Research Capability Engagement with Industry Networking Biotechnology Science Entrepren Eurship

New Programmes Improving Our Campus Student Support Assisting Business Growth Academic Affairs Nurturing Start Ups EnterpriseTraining Staff Improvement Regional Hub Sustainability Building Research Capability Engagement with Industry Networking Biotechnology Science Entrepren Engineering Quality Courses Science Sporting Life CatalystCatalyst BusinessNew Applied Research Kite Project Flying Programmes Design Sustainability Research Life Student Satisfaction Innovation Community Focused Life in Teaching and Learning eats Retention Country Academic Affairs Y a catalyst for attracting smart economy jobs to the region access, transfer & progression W Improving Our Campus eurship estern Living Culture The Sunday Times Supporting Our Students 2nd Overall Institute Good University Guide 2011 Student Services Innovation Building Research Capability Human Resources A New Strategy Smart Learningfor Research People Economy Sporting Community Focused Student Satisfaction Retention a catalyst for attracting smart economy jobs to the region Staff Improvement Stude Quality Courses access, Engagement with Industry transfer& a catalyst for attracting smart economy jobs to the region Assisting Business Growth progression nt Creativity Support Opportunities applied Innovation Enterprise Start Ups researchT in teaching and learning Networking raining Design Regional Hub Engineering Entrepreneurship Science Nurturing Employment Annual Report 2011 Graduate Charles Kilawee with his sister at the 2011 Conferring Our student intake increased in 2010 and 2011, -

Fianna Fáil: Past and Present

Fianna Fáil: Past and Present Alan Byrne Fianna Fáil were the dominant political prompted what is usually referred to as party in Ireland from their first term in gov- a civil-war but as Kieran Allen argues in ernment in the 1930s up until their disas- an earlier issue of this journal, the Free trous 2011 election. The party managed to State in effect mounted a successful counter- enjoy large support from the working class, revolution which was thoroughly opposed to as well as court close links with the rich- the working class movement.3 The defeat est people in Irish society. Often described signalled the end of the aspirations of the as more of a ‘national movement’ than a Irish revolution and the stagnation of the party, their popular support base has now state economically. Emigration was par- plummeted. As this article goes to print, ticularly high in this period, and the state the party (officially in opposition but en- was thoroughly conservative. The Catholic abling a Fine Gael government) is polling Church fostered strong links with Cumann at 26% approval.1 How did a party which na nGaedheal, often denouncing republicans emerged from the losing side of the civil war in its sermons. come to dominate Irish political life so thor- There were distinctive class elements to oughly? This article aims to trace the his- both the pro and anti-treaty sides. The tory of the party, analyse their unique brand Cumann na nGaedheal government drew its of populist politics as well as their relation- base from large farmers, who could rely on ship with Irish capitalism and the working exports to Britain. -

Working Paper of Reflections in the Eyes of a Dying Tiger: Looking Back on Ireland's 1987 Economic Crisis

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Books/Book Chapters School of Marketing 2012 Working Paper of Reflections in the yE es of a Dying Tiger: Looking Back on Ireland's 1987 Economic Crisis Brendan O'Rourke Technological University Dublin, [email protected] John Hogan Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/buschmarbk Part of the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation O'Rourke, B. K., and Hogan, J. Working Paper of Reflections in the yE es of a Dying Tiger: Looking Back on Ireland's 1987 Economic Crisis. Now accepted for publication in Discourse and Crisis: Critical Perspectives : John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Marketing at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books/Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License This a working pre-peer reviewed not for quotation early draft of a later version that is now accepted for publication as O'Rourke, B. K., and Hogan, J. (2013, forthcoming). Reflections in the eyes of a dying tiger: Looking back on Ireland’s 1987 economic crisis In A. De Rycker & Mohd Don, Z. (Eds.), Discourse and Crisis: Critical Perspectives .Amsterdam: John Benjamin . It is under copyright, and the publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use the material in any form. -

The Building of the State the Buildingucd and the Royal College of Scienceof on Merrionthe Street

The Building of the State The BuildingUCD and the Royal College of Scienceof on Merrionthe Street. State UCD and the Royal College of Science on Merrion Street. The Building of the State Science and Engineering with Government on Merrion Street www.ucd.ie/merrionstreet Introduction Although the Government Buildings complex on Merrion Street is one of most important and most widely recognised buildings in Ireland, relatively few are aware of its role in the history of science and technology in the country. At the start of 2011, in preparation for the centenary of the opening of the building, UCD initiated a project seeking to research and record that role. As the work progressed, it became apparent that the story of science and engineering in the building from 1911 to 1989 mirrored in many ways the story of the country over that time, reflecting and supporting national priorities through world wars, the creation of an independent state and the development of a technology sector known and respected throughout the world. All those who worked or studied in the Royal College of Science for Ireland or UCD in Merrion Street – faculty and administrators, students and porters, technicians and librarians – played a part in this story. All those interviewed as part of this project recalled their days in the building with affection and pride. As chair of the committee that oversaw this project, and as a former Merrion Street student, I am delighted to present this publication as a record of UCD’s association with this great building. Professor Orla Feely University College Dublin Published by University College Dublin, 2011. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 1009 Wednesday, No. 5 30 June 2021 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 30/06/2021A00100Ábhair Shaincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Matters 573 30/06/2021A00225Saincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Debate 574 30/06/2021A00250Rail Network 574 30/06/2021B00250Local Authorities 576 30/06/2021C00300Mental Health Services 578 30/06/2021R00400Ceisteanna ó Cheannairí - Leaders’ Questions 608 30/06/2021V00500Estimates for Public Services 2021: Message from Select Committee 617 30/06/2021V00650Ceisteanna ar Reachtaíocht a Gealladh - Questions on Promised Legislation 617 30/06/2021Y02200Ban on Rent Increases Bill 2020: First Stage 626 30/06/2021Z00800Presentation of Estimates: Motion 627 30/06/2021Z01150Estimates for Public Services 2021 628 30/06/2021Z01500Ceisteanna - Questions 628 30/06/2021Z01600Cabinet Committees 628 30/06/2021BB00300Anglo-Irish -

CNI -Press Watch Feb 24

Press Watch Feb. 24 ! CNI PRESS WATCH - Getting ready to be governed by Sinn Fein in the Republic Politics is a strange business. One word and one man’s name that were almost entirely unknown a few years ago now look as if they are going to change modern Irish politics and history: they are ‘Brexit’ and ‘Maurice McCabe’ writes Andy Pollak. The British exit from the EU is the new and deeply unsettling reality that will dominate the politics and economics of this island, north and south, for many years to come. And more immediately, the ramifications of the nauseating campaign by senior echelons of the Garda Siochana to destroy the life and career of an honest, whistle-blowing police sergeant (if this turns out to be true), which will soon end the long career of the Taoiseach, Enda Kenny, bring us closer than ever before to a mould-breaking general election in the Republic. [email protected] Page !1 Press Watch Feb. 24 The breaking of the mould, I believe, will be the entry for the first time of Sinn Fein into government in the Republic as a minority partner. Mary Lou McDonald, the favourite to succeed Gerry Adams as leader of the party in the South, has said it is now open to this option. And the electoral arithmetic points to a Fianna Fail-Sinn Fein coalition as the most likely outcome of an election in the near future. Fianna Fail leader Micheál Martin has so far set his face against such an outcome, determined that an alliance with Sinn Fein would not see his constitutional republican party suffer the same fate as the SDLP in the North. -

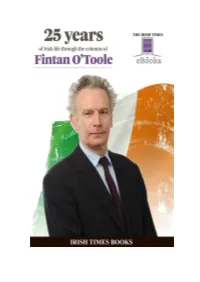

PDF(All Devices)

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2014. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Watching from a window as we all stay the same ................................................................ 4 Emigration- an Irish guarantor of continuity ........................................................................ 7 Completing a transaction called Ireland ................................................................................ 9 In the land of wink and nod ................................................................................................. 13 Rhetoric, reality and the proper Charlie .............................................................................. 16 The rise to becoming a beggar on horseback ...................................................................... 19 The real spiritual home of Fianna Fáil ................................................................................ 21 Electorate gives ethics the cold shoulders ........................................................................... 24 Corruption well known – and nothing was done ................................................................ 26 Questions the IRA is happy to ignore ................................................................................