"Your Sexagenarian Lover..."

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 Years in Rock History

HISTORY AEROSMITH 50 YEARS IN ROCK PART THREE AEROSMITH 50 YEARS IN ROCK PART THREE 1995–1999 The year of 1995 is for AEROSMITH marked by AEROSMITH found themselves in a carousel the preparations of a new album, in which the of confusions, intrigues, great changes, drummer Joey Kramer did not participate in its termination of some collaboration, returns first phase. At that time, he was struggling with and new beginnings. They had already severe depressive states. After the death of his experienced all of it many times during their father, everything that had accumulated inside career before, but this time on a completely him throughout his life and could no longer be different level. The resumption of collaboration ignored, came to the surface. Unsuspecting and with their previous record company was an 2,000 miles away from the other members of encouragement and a guarantee of a better the band, he undergoes treatment. This was tomorrow for the band while facing unfavorable disrupted by the sudden news of recording circumstances. The change of record company the basics of a new album with a replacement was, of course, sweetened by a lucrative drummer. Longtime manager Tim Collins handled offer. Columbia / Sony valued AEROSMITH the situation in his way and tried to get rid of at $ 30 million and offered the musicians Joey Kramer without the band having any idea a contract that was certainly impossible about his actions. In general, he tried to keep the to reject. AEROSMITH returned under the musicians apart so that he had everything under wing of a record company that had stood total control. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Aerosmith Returns for Newly Announced Second Leg of ‘The Global Warming Tour’ Tickets Go on Sale September 24

AEROSMITH RETURNS FOR NEWLY ANNOUNCED SECOND LEG OF ‘THE GLOBAL WARMING TOUR’ TICKETS GO ON SALE SEPTEMBER 24 BAND’S NEW ALBUM ‘MUSIC FROM ANOTHER DIMENSION’ STREETS NOVEMBER 6 “Brad Whitford and Joe Perry are playing better guitar than ever. Steven Tyler is playful, happy, and singing all of those impossible high notes. Joey Kramer has a drum groove like no other. And Tom Hamilton…continues to be the steady anchor to this ship.” --Duff McKagan (Guns N’ Roses, Velvet Revolver, Loaded) SEATTLE WEEKLY, August 10, 2012 AEROSMITH ain’t messing around. America’s greatest rock band delivered absolutely killer sets on the first leg of their triumphant, sold-out The Global Warming Tour this past summer, with critics dropping comments like (we kid you not, see below) “stunning…jaw-dropping…impassioned intensity…seamless swagger...epic rock moments…a wonder to behold…Aerosmith always managed to reinvent itself for the masses without losing its inherent musicality...Make no mistake, Aerosmith remains king.” They ain’t done yet. More prisoners will be taken when Steven Tyler (vocals), Joe Perry (guitar), Brad Whitford (guitar), Tom Hamilton (bass) and Joey Kramer (drums) return for the second leg of The Global Warming Tour launching November 8. The month-long, 14-city arena tour will take the band to New York City (Madison Square Garden), Los Angeles (Staples Center) and Las Vegas (MGM Grand Garden Arena), among other cities. They’re fully armed with career-defining hits and blazing songs from their new album MUSIC FROM ANOTHER DIMENSION, out November 6 on Columbia Records. They’re the only band of their stature with all-original members and who are playing better than ever before. -

Spy Kids, in Which She Starred As Carmen Cortez

‘CHRISTMAS MADE TO ORDER’ Cast Bios ALEXA PENAVEGA (Gretchen) – Alexa PenaVega, a Miami native, is an actress and a singer. Her career began as a young girl in 1996, when she starred as Jo Harding in the hit film Twister. After that, she guest-starred in various television shows and films such as “The Bernie Mac Show,” “ER” and “Ghost Whisperer.” The movie that catapulted her to worldwide fame was the 2001 film Spy Kids, in which she starred as Carmen Cortez. After the enormous success of that movie there were two sequels: Spy Kids 2: The Island of Lost Dreams and Spy Kids 3D: Game Over, as well as the 2011 reprisal, Spy Kids: All the Time in the World. PenaVega went on to appear in many other films such as Sleepover, State’s Evidence, Odd Girl Out, Walkout, Remember the Daze, Repo! The Genetic Opera, and The Pregnancy Project. While PenaVega has an impressive movie filmography, she has also had massive success in other areas of the entertainment industry. She played Penny in Hairspray on Broadway, had TV roles in shows such as “Ruby & the Rockits” and “Big Time Rush,” appeared in Aerosmith’s “Legendary Child” and was a contestant on Season 21 of “Dancing with the Stars.” PenaVega is also a singer – over the course of her Spy Kids career she contributed three songs to the various movie soundtracks (“Isle of Dreams,” “Game Over” and “Heart Drive”). She also sang “Christmas is the Time to Say I Love You” for Walt Disney Records’ compilation album Songs to Celebrate the 25 Days of Christmas in 2009. -

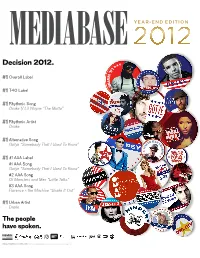

Decision 2012

YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 Decision 2012. #1 Overall Label #1 T40 Label #1 Rhythmic Song Drake f/ Lil Wayne “The Motto” #1 Rhythmic Artist Drake Alternative Song #1 HAW ER T Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” Y H A O M R N H E H #1 #1 AAA Label #1 AAA Song Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” #2 AAA Song Of Monsters and Men “Little Talks” #3 AAA Song Florence + the Machine “Shake It Out” #1 Urban Artist Drake The people have spoken. www.republicrecords.com c 2012 Universal Republic Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. REPUBLIC LANDS TOP SPOT OVERALL Republic Top 40 Champ Island Def Jam Takes Rhythmic & Urban Republic t o o k t h e t o p s p o t f o r t h e 2 0 1 2 c h a r t y e a r, w h i c h w e n t f r o m N o v e m b e r 2 0 , 2 0 1 1 - N o v e m b e r 17, 2012. The label was also #1 at Top 40 and Triple A, while finishing #2 at Rhythmic, #3 at Urban, and #4 at AC. Their overall share was 13.5%. Leading the way for Republic was newcomer Gotye, who had one of the year’s biggest hits with “Somebody That I Used To Know.” A big year from Drake and Nicki Minaj also contributed to the label’s success, as well as strong performances for Florence + The Machine, Volbeat, and Of Monsters And Men to name a few. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

V06.N03-11.14.12

Small Business of the Year! FREE Vol. Vol. 3, 6, No. No. 11 3 Published Every Other Published Wednesday Every www.venturabreeze.comOther Wednesday November 14 – November March 10 27, - 23, 201 20102 Thanksgiving luncheon for seniors Seniors, celebrate America’s unique fall holiday with a tra- ditional Thanksgiving meal sponsored by the City of Ventura Westside Cafe at 550 N. Ventura Avenue, on Wednesday, Nov. 21, 11:30am–1pm. Suggested donation is $3 for those 60 and over and set meal price of $5 for diners under 60. Marlyss Auster has returned to Ventura. The Ventura Botanical Call 648-2829 for more infor- VVCB Gardens has taken its first step mation. The Ventura Botanical Gardens The sky was overcast as the upper preliminary data collected in the Estuary announces celebrated the Grand Opening of its parking lot behind City Hall filled up last summer. Building on the outcomes first installation, the Demonstration with donors to the Foot by Foot campaign from the last stakeholder meeting in July, new executive Trail, on Saturday, October 20th at and members of the Ventura Botanical attendees also had the opportunity to noon. After six years of planning and Gardens for the party celebrating the consider more information about alter- community outreach and fundraising opening of the Demonstration Trail, natives that would reduce the amount of director the Gardens is becoming a reality. Continued on page 15 water released into the Estuary and reuse The Ventura Visitors and Conven- it in other ways. tion Bureau (VVCB) recently announced Screened for initial feasibility, a Marlyss M. -

Aerosmith: La Banda Indestructible

It's only rock & roll | Pep Saña | Actualitzat el 13/04/2016 a les 18:39 Aerosmith: La banda indestructible Malgrat la seva durabilitat i popularitat durant més de quatre dècades, Aerosmith mai han rebut el respecte que mereixen per part dels crítics. Als anys 70, sempre van ser considerats imitadors de segona dels Rolling Stones. A causa de la semblança física i escènica entre Steven Tyler i Mick Jagger i entre Joe Perry i Keith Richards, Aerosmith van ser inicialment etiquetats de voler-se promocionar com els Rolling Stones americans. Però mentre que The Rolling Stones estaven decididament orientats cap a un so essencialment lligat al rock'n'roll, Aerosmith, amb el volum més alt, es movien entre un hard melodic i un boogie ?metalero?. La veritable semblança entre els dos grups, nomes eren els morros de Tyler i de Jagger. Però la indestructible banda de Boston sempre ha tingut la seva originalitat, gràcies a la veu del seu líder Steven Tyler, les guitarres de Joe Perry i Brad Whitford, i una imponent secció rítmica amb Tom Hamilton al baix i Joey Kramer a la bateria. A diferència de molts dels seus similars, Aerosmith sempre han mantingut una propera connexió amb les seves arrels de blues que encara avui influeixen la seva música fins a la peça més comercial. L'habilitat d'Aerosmith de confondre als seus crítics contínua sent una de les seves millors característiques, cap al final dels anys 80, la banda, ferida per problemes de droga i tensions entre ells, va ser àmpliament considerada com acabada per la indústria musical. -

Year-End Edition Mediabase 2012 Overall Label Chart Share

CANADIAN YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 OVERALL LABEL CHART SHARE RANK LABEL 2012 LABEL SHARE 1 UMG 34.93% 2 Sony 18.14% 3 Warner 16.50% 4 e MI 11.34% 5 o pen road 2.92% 6 BMLG 2.24% 7 BeG G arS 2.07% 8 ULtra 1.72% 9 C p reCordS 1.20% 10 e one 1.18% 11 Independent 0.85% 12 Map Le/Fontana 0.84% 13 Lo Up one 0.76% 14 MdM 0.71% 15 Die n Alone 0.61% © 2012 Mediabase Research 2 0 1 2 2 TOP 40 LABEL CHART SHARE RANK LABEL 2012 LABEL SHARE 1 UMG 46.17% 2 Sony 17.08% 3 Warner 16.68% 4 e MI 8.71% 5 ULtra 3.61% 6 C p reCordS 2.26% 7 BeG G arS 2.25% 8 Lo Up one 1.31% 9 t anjoLa 1.15% 10 BMLG 0.78% TOP 40 MOST PLAYED ARTISTS RANK ARTIST LABEL 1 FLa o rId Poe Boy/Atlantic 2 DAI V d GUetta Astralwerks/Capitol 3 rHI ANNA Def Jam/IDJMG 4 K aty perry Capitol 5 DRAKe YMCMB/Republic 6 M aroon 5 A&M/Octone/Interscope 7 n ICKI MInaj YMCMB/Republic 8 C ARLy rae jepSen 604/Universal 9 FUn. Fueled By Ramen/RRP 10 Hde LEY Universal Music Canada © 2012 Mediabase Research 2 0 1 2 4 TOP 40 YEAR-END CHART RANK ARTIST TITLE LABEL 1 FLO RIDA Good Feeling Poe Boy/Atlantic 2 RIHANNA f/CALVIN HARRIS We Found Love Def Jam/IDJMG 3 NICKI MINAJ Starships YMCMB/Republic 4 FLO RIDA f/SIA Wild Ones Poe Boy/Atlantic 5 CARLY RAE JEPSEN Call Me Maybe 604/Universal 6 LMFAO Sexy And I Know It Interscope 7 THE WANTED Glad You Came Mercury/IDJMG 8 GOTYE Somebody That I Used To Know Fairfax/Republic 9 MAROON 5 f/WIZ KHALIFA Payphone A&M/Octone/Interscope 10 RIHANNA Where Have You Been Def Jam/IDJMG 11 DAVID GUETTA f/SIA Titanium Astralwerks/Capitol 12 FUN. -

2010-2011 Specialized High Schools Student Handbook

SPECIALIZED HIGH SCHOOLS STUDENT HANDBOOK 2010–2011 7 7 6 6 3 3 2 2 n The Bronx High School of Science n The Brooklyn Latin School n Brooklyn Technical High School n High School for Mathematics, Science and Engineering at the City College n High School of American Studies at Lehman College n Queens High School for the Sciences at York College For more information, call 311 or visit www.nyc.gov/schools MICHAEL R. BLOOMBERG, MAYOR JOEL I. KLEIN, CHANCELLOR n Staten Island Technical High School n Stuyvesant High School THE n Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts 7 6 3 2 It is the policy of the Department of Education of the City of New York not to discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, citizenship/immigration status, age, disability, marital status, sex, sexual orientation or gender identity/expression in its educational programs and activities, and to maintain an environment free of sexual harassment, as required by law. Inquiries regarding compliance with appropriate laws may be directed to: Director, Office of Equal Opportunity, 65 Court Street, Room 923, Brooklyn, New York 11201, Telephone 718-935-3320. Cover artwork by Kenneth Candelas, student at Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. Sample test items are taken from materials copyright © 1983-2010, NCS Pearson, Inc., 5601 Green Valley Drive, Bloomington, MN 55437. 2 Contents Message to Students and Parents/Guardians . 4 SECTION 1: The Specialized High Schools uThe Bronx High School of Science . 5 The Brooklyn Latin School . -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE . WASHINGTON, D.C. 202-10 Q y 9 / ' a * IN REPLY Ul.II.R t o : i *» H34-HR APR 2 1 1972 Mr. Frank F. Bias Director of Commerce , Department _ of Commerce______ _1 _____________ ________________ _ Post Office Box 682 Agana, Guam 96910 Dear Mr. Bias: « We are pleased to reply to your letter concerning Guam’s participation in the historic preservation grants-in-aid program of the National Park Service, administered by the National Register of Historic Places. Under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (80 Stat. 915), as amended, Guam is eligible to participate in the program. The listing of apportionments to which you refer is, I presume, the Fiscal Year 1972 apportionment. It shows the allocations for States that previously submitted to the National Park Service projections of their matching capabilities and needs for historic preservation. For any State that did not provide such projections, .5 of one percent, or $29,900, of the Fiscal Year appropriation passed by Congress was put in reserve. You will be pleased to learn that the original stipulation that the State apply for its reserve by March 31, 1972, has been discontinued, and the - funds are still being held in reserve for Guam. You are doubtless anxious to know how you may receive funds from that reserve. Under the Act of 1966, a State is eligible to receive grants to assist in its survey and planning program and In acquiring or developing historic properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places only after it has submitted a State Historic Preservation Plan that has received National-Park Service approval. -

Aerosmith Lyrics Trivia Quiz

AEROSMITH LYRICS TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> You may be high, you may be low. You may be rich yeah, you may be poor. Brother when the Lord get ready... a. You Gotta Move b. Shut Up and Dance c. Reefer Head Woman d. S.O.S. (Too Bad) 2> Come Here baby. You know you drive me up a wall the way you make good on all the nasty tricks you pull... a. Sunshine b. The Hand That Feeds c. Crazy d. Stop Messin' Around 3> Cruise into a bar on the shore. Her picture graced the grime on the door. She's a long lost love at first bite. Baby maybe you're wrong... a. Something's Gotta Give b. Uncle Salty c. Sweet Emotion d. Dude (Looks Like a Lady) 4> I could stay awake just to hear you breathing. Watch you smile while you are sleeping, while you're far away and dreaming... a. I Don't Want to Miss a Thing b. Same Old Song and Dance c. Lover Alot d. Rag Doll 5> There's somethin' wrong with the world today, I don't know what it is. Something's wrong with our eyes... a. Last Child b. Lick and a Promise c. Kings and Queens d. Livin' on the Edge 6> New York City blues. East side, West side blues. Throw me in the slam, catch me if you can. Believe that you're wearing, tearing me apart... a. Rats in the Cellar b. Legendary Child c. Jaded d. Hole in My Soul 7> Get yourself cooler, lay yourself low.