Geometry of Simplexes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

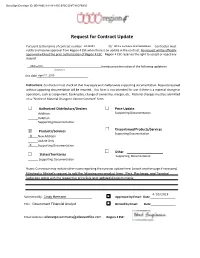

Request for Contract Update

DocuSign Envelope ID: 0E48A6C9-4184-4355-B75C-D9F791DFB905 Request for Contract Update Pursuant to the terms of contract number________________R142201 for _________________________ Office Furniture and Installation Contractor must notify and receive approval from Region 4 ESC when there is an update in the contract. No request will be officially approved without the prior authorization of Region 4 ESC. Region 4 ESC reserves the right to accept or reject any request. Allsteel Inc. hereby provides notice of the following update on (Contractor) this date April 17, 2019 . Instructions: Contractor must check all that may apply and shall provide supporting documentation. Requests received without supporting documentation will be returned. This form is not intended for use if there is a material change in operations, such as assignment, bankruptcy, change of ownership, merger, etc. Material changes must be submitted on a “Notice of Material Change to Vendor Contract” form. Authorized Distributors/Dealers Price Update Addition Supporting Documentation Deletion Supporting Documentation Discontinued Products/Services X Products/Services Supporting Documentation X New Addition Update Only X Supporting Documentation Other States/Territories Supporting Documentation Supporting Documentation Notes: Contractor may include other notes regarding the contract update here: (attach another page if necessary). Attached is Allsteel's request to add the following new product lines: Park, Recharge, and Townhall Collection along with the respective price -

![The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8642/the-geometry-of-nim-arxiv-1109-6712v1-math-co-30-48642.webp)

The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30

The Geometry of Nim Kevin Gibbons Abstract We relate the Sierpinski triangle and the game of Nim. We begin by defining both a new high-dimensional analog of the Sierpinski triangle and a natural geometric interpretation of the losing positions in Nim, and then, in a new result, show that these are equivalent in each finite dimension. 0 Introduction The Sierpinski triangle (fig. 1) is one of the most recognizable figures in mathematics, and with good reason. It appears in everything from Pascal's Triangle to Conway's Game of Life. In fact, it has already been seen to be connected with the game of Nim, albeit in a very different manner than the one presented here [3]. A number of analogs have been discovered, such as the Menger sponge (fig. 2) and a three-dimensional version called a tetrix. We present, in the first section, a generalization in higher dimensions differing from the more typical simplex generalization. Rather, we define a discrete Sierpinski demihypercube, which in three dimensions coincides with the simplex generalization. In the second section, we briefly review Nim and the theory behind optimal play. As in all impartial games (games in which the possible moves depend only on the state of the game, and not on which of the two players is moving), all possible positions can be divided into two classes - those in which the next player to move can force a win, called N-positions, and those in which regardless of what the next player does the other player can force a win, called P -positions. -

Notes Has Not Been Formally Reviewed by the Lecturer

6.896 Topics in Algorithmic Game Theory February 22, 2010 Lecture 6 Lecturer: Constantinos Daskalakis Scribe: Jason Biddle, Debmalya Panigrahi NOTE: The content of these notes has not been formally reviewed by the lecturer. It is recommended that they are read critically. In our last lecture, we proved Nash's Theorem using Broweur's Fixed Point Theorem. We also showed Brouwer's Theorem via Sperner's Lemma in 2-d using a limiting argument to go from the discrete combinatorial problem to the topological one. In this lecture, we present a multidimensional generalization of the proof from last time. Our proof differs from those typically found in the literature. In particular, we will insist that each step of the proof be constructive. Using constructive arguments, we shall be able to pin down the complexity-theoretic nature of the proof and make the steps algorithmic in subsequent lectures. In the first part of our lecture, we present a framework for the multidimensional generalization of Sperner's Lemma. A Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube • A Legal Coloring Rule • In the second part, we formally state Sperner's Lemma in n dimensions and prove it using the following constructive steps: Colored Envelope Construction • Definition of the Walk • Identification of the Starting Simplex • Direction of the Walk • 1 Framework Recall that in the 2-dimensional case we had a square which was divided into triangles. We had also defined a legal coloring scheme for the triangle vertices lying on the boundary of the square. Now let us extend those concepts to higher dimensions. 1.1 Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube We begin by introducing the n-simplex as the n-dimensional analog of the triangle in 2 dimensions as shown in Figure 1. -

1 Lifts of Polytopes

Lecture 5: Lifts of polytopes and non-negative rank CSE 599S: Entropy optimality, Winter 2016 Instructor: James R. Lee Last updated: January 24, 2016 1 Lifts of polytopes 1.1 Polytopes and inequalities Recall that the convex hull of a subset X n is defined by ⊆ conv X λx + 1 λ x0 : x; x0 X; λ 0; 1 : ( ) f ( − ) 2 2 [ ]g A d-dimensional convex polytope P d is the convex hull of a finite set of points in d: ⊆ P conv x1;:::; xk (f g) d for some x1;:::; xk . 2 Every polytope has a dual representation: It is a closed and bounded set defined by a family of linear inequalities P x d : Ax 6 b f 2 g for some matrix A m d. 2 × Let us define a measure of complexity for P: Define γ P to be the smallest number m such that for some C s d ; y s ; A m d ; b m, we have ( ) 2 × 2 2 × 2 P x d : Cx y and Ax 6 b : f 2 g In other words, this is the minimum number of inequalities needed to describe P. If P is full- dimensional, then this is precisely the number of facets of P (a facet is a maximal proper face of P). Thinking of γ P as a measure of complexity makes sense from the point of view of optimization: Interior point( methods) can efficiently optimize linear functions over P (to arbitrary accuracy) in time that is polynomial in γ P . ( ) 1.2 Lifts of polytopes Many simple polytopes require a large number of inequalities to describe. -

Interval Vector Polytopes

Interval Vector Polytopes By Gabriel Dorfsman-Hopkins SENIOR HONORS THESIS ROSA C. ORELLANA, ADVISOR DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS DARTMOUTH COLLEGE JUNE, 2013 Contents Abstract iv 1 Introduction 1 2 Preliminaries 4 2.1 Convex Polytopes . 4 2.2 Lattice Polytopes . 8 2.2.1 Ehrhart Theory . 10 2.3 Faces, Face Lattices and the Dual . 12 2.3.1 Faces of a Polytope . 12 2.3.2 The Face Lattice of a Polytope . 15 2.3.3 Duality . 18 2.4 Basic Graph Theory . 22 3IntervalVectorPolytopes 23 3.1 The Complete Interval Vector Polytope . 25 3.2 TheFixedIntervalVectorPolytope . 30 3.2.1 FlowDimensionGraphs . 31 4TheIntervalPyramid 38 ii 4.1 f-vector of the Interval Pyramid . 40 4.2 Volume of the Interval Pyramid . 45 4.3 Duality of the Interval Pyramid . 50 5 Open Questions 57 5.1 Generalized Interval Pyramid . 58 Bibliography 60 iii Abstract An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector where all the ones appear consecutively. An { } interval vector polytope is the convex hull of a set of interval vectors in Rn.Westudy several classes of interval vector polytopes which exhibit interesting combinatorial- geometric properties. In particular, we study a class whose volumes are equal to the catalan numbers, another class whose legs always form a lattice basis for their affine space, and a third whose face numbers are given by the pascal 3-triangle. iv Chapter 1 Introduction An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector in Rn such that the ones (if any) occur consecu- { } tively. These vectors can nicely and discretely model scheduling problems where they represent the length of an uninterrupted activity, and so understanding the combi- natorics of these vectors is useful in optimizing scheduling problems of continuous activities of certain lengths. -

Simplicial Complexes

46 III Complexes III.1 Simplicial Complexes There are many ways to represent a topological space, one being a collection of simplices that are glued to each other in a structured manner. Such a collection can easily grow large but all its elements are simple. This is not so convenient for hand-calculations but close to ideal for computer implementations. In this book, we use simplicial complexes as the primary representation of topology. Rd k Simplices. Let u0; u1; : : : ; uk be points in . A point x = i=0 λiui is an affine combination of the ui if the λi sum to 1. The affine hull is the set of affine combinations. It is a k-plane if the k + 1 points are affinely Pindependent by which we mean that any two affine combinations, x = λiui and y = µiui, are the same iff λi = µi for all i. The k + 1 points are affinely independent iff P d P the k vectors ui − u0, for 1 ≤ i ≤ k, are linearly independent. In R we can have at most d linearly independent vectors and therefore at most d+1 affinely independent points. An affine combination x = λiui is a convex combination if all λi are non- negative. The convex hull is the set of convex combinations. A k-simplex is the P convex hull of k + 1 affinely independent points, σ = conv fu0; u1; : : : ; ukg. We sometimes say the ui span σ. Its dimension is dim σ = k. We use special names of the first few dimensions, vertex for 0-simplex, edge for 1-simplex, triangle for 2-simplex, and tetrahedron for 3-simplex; see Figure III.1. -

Degrees of Freedom in Quadratic Goodness of Fit

Submitted to the Annals of Statistics DEGREES OF FREEDOM IN QUADRATIC GOODNESS OF FIT By Bruce G. Lindsay∗, Marianthi Markatouy and Surajit Ray Pennsylvania State University, Columbia University, Boston University We study the effect of degrees of freedom on the level and power of quadratic distance based tests. The concept of an eigendepth index is introduced and discussed in the context of selecting the optimal de- grees of freedom, where optimality refers to high power. We introduce the class of diffusion kernels by the properties we seek these kernels to have and give a method for constructing them by exponentiating the rate matrix of a Markov chain. Product kernels and their spectral decomposition are discussed and shown useful for high dimensional data problems. 1. Introduction. Lindsay et al. (2008) developed a general theory for good- ness of fit testing based on quadratic distances. This class of tests is enormous, encompassing many of the tests found in the literature. It includes tests based on characteristic functions, density estimation, and the chi-squared tests, as well as providing quadratic approximations to many other tests, such as those based on likelihood ratios. The flexibility of the methodology is particularly important for enabling statisticians to readily construct tests for model fit in higher dimensions and in more complex data. ∗Supported by NSF grant DMS-04-05637 ySupported by NSF grant DMS-05-04957 AMS 2000 subject classifications: Primary 62F99, 62F03; secondary 62H15, 62F05 Keywords and phrases: Degrees of freedom, eigendepth, high dimensional goodness of fit, Markov diffusion kernels, quadratic distance, spectral decomposition in high dimensions 1 2 LINDSAY ET AL. -

![Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4942/arxiv-1910-10745v1-cond-mat-str-el-23-oct-2019-2-2-symmetry-protected-time-crystals-304942.webp)

Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals

A Brief History of Time Crystals Vedika Khemania,b,∗, Roderich Moessnerc, S. L. Sondhid aDepartment of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA bDepartment of Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, USA cMax-Planck-Institut f¨urPhysik komplexer Systeme, 01187 Dresden, Germany dDepartment of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544, USA Abstract The idea of breaking time-translation symmetry has fascinated humanity at least since ancient proposals of the per- petuum mobile. Unlike the breaking of other symmetries, such as spatial translation in a crystal or spin rotation in a magnet, time translation symmetry breaking (TTSB) has been tantalisingly elusive. We review this history up to recent developments which have shown that discrete TTSB does takes place in periodically driven (Floquet) systems in the presence of many-body localization (MBL). Such Floquet time-crystals represent a new paradigm in quantum statistical mechanics — that of an intrinsically out-of-equilibrium many-body phase of matter with no equilibrium counterpart. We include a compendium of the necessary background on the statistical mechanics of phase structure in many- body systems, before specializing to a detailed discussion of the nature, and diagnostics, of TTSB. In particular, we provide precise definitions that formalize the notion of a time-crystal as a stable, macroscopic, conservative clock — explaining both the need for a many-body system in the infinite volume limit, and for a lack of net energy absorption or dissipation. Our discussion emphasizes that TTSB in a time-crystal is accompanied by the breaking of a spatial symmetry — so that time-crystals exhibit a novel form of spatiotemporal order. -

THE DIMENSION of a VECTOR SPACE 1. Introduction This Handout

THE DIMENSION OF A VECTOR SPACE KEITH CONRAD 1. Introduction This handout is a supplementary discussion leading up to the definition of dimension of a vector space and some of its properties. We start by defining the span of a finite set of vectors and linear independence of a finite set of vectors, which are combined to define the all-important concept of a basis. Definition 1.1. Let V be a vector space over a field F . For any finite subset fv1; : : : ; vng of V , its span is the set of all of its linear combinations: Span(v1; : : : ; vn) = fc1v1 + ··· + cnvn : ci 2 F g: Example 1.2. In F 3, Span((1; 0; 0); (0; 1; 0)) is the xy-plane in F 3. Example 1.3. If v is a single vector in V then Span(v) = fcv : c 2 F g = F v is the set of scalar multiples of v, which for nonzero v should be thought of geometrically as a line (through the origin, since it includes 0 · v = 0). Since sums of linear combinations are linear combinations and the scalar multiple of a linear combination is a linear combination, Span(v1; : : : ; vn) is a subspace of V . It may not be all of V , of course. Definition 1.4. If fv1; : : : ; vng satisfies Span(fv1; : : : ; vng) = V , that is, if every vector in V is a linear combination from fv1; : : : ; vng, then we say this set spans V or it is a spanning set for V . Example 1.5. In F 2, the set f(1; 0); (0; 1); (1; 1)g is a spanning set of F 2. -

Slices, Slabs, and Sections of the Unit Hypercube

Slices, Slabs, and Sections of the Unit Hypercube Jean-Luc Marichal Michael J. Mossinghoff Institute of Mathematics Department of Mathematics University of Luxembourg Davidson College 162A, avenue de la Fa¨ıencerie Davidson, NC 28035-6996 L-1511 Luxembourg USA Luxembourg [email protected] [email protected] Submitted: July 27, 2006; Revised: August 6, 2007; Accepted: January 21, 2008; Published: January 29, 2008 Abstract Using combinatorial methods, we derive several formulas for the volume of convex bodies obtained by intersecting a unit hypercube with a halfspace, or with a hyperplane of codimension 1, or with a flat defined by two parallel hyperplanes. We also describe some of the history of these problems, dating to P´olya’s Ph.D. thesis, and we discuss several applications of these formulas. Subject Class: Primary: 52A38, 52B11; Secondary: 05A19, 60D05. Keywords: Cube slicing, hyperplane section, signed decomposition, volume, Eulerian numbers. 1 Introduction In this note we study the volumes of portions of n-dimensional cubes determined by hyper- planes. More precisely, we study slices created by intersecting a hypercube with a halfspace, slabs formed as the portion of a hypercube lying between two parallel hyperplanes, and sections obtained by intersecting a hypercube with a hyperplane. These objects occur natu- rally in several fields, including probability, number theory, geometry, physics, and analysis. In this paper we describe an elementary combinatorial method for calculating volumes of arbitrary slices, slabs, and sections of a unit cube. We also describe some applications that tie these geometric results to problems in analysis and combinatorics. Some of the results we obtain here have in fact appeared earlier in other contexts. -

Linear Algebra Handout

Artificial Intelligence: 6.034 Massachusetts Institute of Technology April 20, 2012 Spring 2012 Recitation 10 Linear Algebra Review • A vector is an ordered list of values. It is often denoted using angle brackets: ha; bi, and its variable name is often written in bold (z) or with an arrow (~z). We can refer to an individual element of a vector using its index: for example, the first element of z would be z1 (or z0, depending on how we're indexing). Each element of a vector generally corresponds to a particular dimension or feature, which could be discrete or continuous; often you can think of a vector as a point in Euclidean space. p 2 2 2 • The magnitude (also called norm) of a vector x = hx1; x2; :::; xni is x1 + x2 + ::: + xn, and is denoted jxj or kxk. • The sum of a set of vectors is their elementwise sum: for example, ha; bi + hc; di = ha + c; b + di (so vectors can only be added if they are the same length). The dot product (also called scalar product) of two vectors is the sum of their elementwise products: for example, ha; bi · hc; di = ac + bd. The dot product x · y is also equal to kxkkyk cos θ, where θ is the angle between x and y. • A matrix is a generalization of a vector: instead of having just one row or one column, it can have m rows and n columns. A square matrix is one that has the same number of rows as columns. A matrix's variable name is generally a capital letter, often written in bold. -

The Simplex Algorithm in Dimension Three1

The Simplex Algorithm in Dimension Three1 Volker Kaibel2 Rafael Mechtel3 Micha Sharir4 G¨unter M. Ziegler3 Abstract We investigate the worst-case behavior of the simplex algorithm on linear pro- grams with 3 variables, that is, on 3-dimensional simple polytopes. Among the pivot rules that we consider, the “random edge” rule yields the best asymptotic behavior as well as the most complicated analysis. All other rules turn out to be much easier to study, but also produce worse results: Most of them show essentially worst-possible behavior; this includes both Kalai’s “random-facet” rule, which is known to be subexponential without dimension restriction, as well as Zadeh’s de- terministic history-dependent rule, for which no non-polynomial instances in general dimensions have been found so far. 1 Introduction The simplex algorithm is a fascinating method for at least three reasons: For computa- tional purposes it is still the most efficient general tool for solving linear programs, from a complexity point of view it is the most promising candidate for a strongly polynomial time linear programming algorithm, and last but not least, geometers are pleased by its inherent use of the structure of convex polytopes. The essence of the method can be described geometrically: Given a convex polytope P by means of inequalities, a linear functional ϕ “in general position,” and some vertex vstart, 1Work on this paper by Micha Sharir was supported by NSF Grants CCR-97-32101 and CCR-00- 98246, by a grant from the U.S.-Israeli Binational Science Foundation, by a grant from the Israel Science Fund (for a Center of Excellence in Geometric Computing), and by the Hermann Minkowski–MINERVA Center for Geometry at Tel Aviv University.