CD44 Sorted Cells Have an Augmented Potential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Screening and Identification of Key Biomarkers in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Based on Bioinformatics Analysis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.21.423889; this version posted December 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Screening and identification of key biomarkers in clear cell renal cell carcinoma based on bioinformatics analysis Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 , Iranna Kotturshetti 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. 3. Department of Ayurveda, Rajiv Gandhi Education Society`s Ayurvedic Medical College, Ron, Karnataka 562209, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.21.423889; this version posted December 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is one of the most common types of malignancy of the urinary system. The pathogenesis and effective diagnosis of ccRCC have become popular topics for research in the previous decade. In the current study, an integrated bioinformatics analysis was performed to identify core genes associated in ccRCC. An expression dataset (GSE105261) was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database, and included 26 ccRCC and 9 normal kideny samples. Assessment of the microarray dataset led to the recognition of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), which was subsequently used for pathway and gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. -

Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Gastric Adenocarcinoma

Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bass, A. J., V. Thorsson, I. Shmulevich, S. M. Reynolds, M. Miller, B. Bernard, T. Hinoue, et al. 2014. “Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma.” Nature 513 (7517): 202-209. doi:10.1038/nature13480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ nature13480. Published Version doi:10.1038/nature13480 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12987344 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Nature. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 September 22. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Nature. 2014 September 11; 513(7517): 202–209. doi:10.1038/nature13480. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma A full list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the article. Abstract Gastric cancer is a leading cause of cancer deaths, but analysis of its molecular and clinical characteristics has been complicated by histological and aetiological heterogeneity. Here we describe a comprehensive molecular evaluation of 295 primary gastric adenocarcinomas as part of The Cancer -

HER2 Positive and HER2 Negative Classical Type Invasive Lobular Carcinomas: Comparison of Clinicopathologic Features

Article HER2 Positive and HER2 Negative Classical Type Invasive Lobular Carcinomas: Comparison of Clinicopathologic Features Lin He 1, Ellen Araj 1 and Yan Peng 1,2,* 1 Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 6201 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX 75235, USA; [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (E.A.) 2 Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX 75235, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive (+) classical type invasive lobular carcinoma (cILC) of the breast is extremely rare and its clinicopathologic features have not been well characterized. We compared features of HER2(+) and HER2 negative (−) cILCs. A total of 29 cases were identified from the clinical database at our institution from 2011-2019; 9 were HER2(+) cILC tumors and 20 were HER2(−) cILC tumors. The results reveal that HER2(+) cILC group had significantly increased Ki-67 expression and reduced estrogen receptor (ER) expression compared to HER2(−) cILC group (both p < 0.05). In addition, HER2(+) cILCs tended to be diagnosed at a younger age and more common in the left breast, and appeared to have a higher frequency of nodal or distant metastases. These clinicopathologic features suggest HER2(+) cILC tumors may have more aggressive behavior than their HER2(−) counterpart although both groups of tumors showed similar morphologic features. Future directions of the study: (1) To conduct a multi-institutional study with a larger case series of HER2(+) cILC to further characterize its clinicopathologic features; (2) to compare molecular profiles by next generation sequencing (NGS) assay between HER2(+) cILC and HER2(−) cILC cases to better understand tumor biology of this rare subset of HER2(+) breast cancer; Citation: He, L.; Araj, E.; Peng, Y. -

MARKER PANEL Figure 1

Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition MARKER PANEL Figure 1. E-cadherin (A-F) and N-cadherin (G-L) expression profiles in normal human tissues shown by IHC with the Anti-CDH1 antibody AMAb90863 and the Anti-CDH2 antibody AMAb91220. Note the differential expression of two cadherins in colon (A, J), duodenum (B, K), cervix (C, L), cerebellum (D, G), heart (E, H) and testis (F, I). Inset on J shows CDH2- immunoreactivity in the peripheral ganglion neurons in rectum. A A B B Figure 2. Western blot using Anti-CDH1 antibody AMAb90863 (A) and Anti-CDH2 antibody AMAb91220 (B). Blot A: Lane 1: Marker [kDa], Lane 2: Human cell line MCF-7 (posi- tive), Lane 3: Human cell line SK-BR-3 (negative), Lane 4: Human cell line HeLa (nega- Figure 3. E-cadherin – beta-catenin protein-protein interactions tive). Blot B: Lane 1: Marker [kDa], Lane 2 Human U-251 MG (positive). shown by in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) in the epi- thelium of normal fallopian tube (A). The Anti-CDH1 mouse Cover image: monoclonal antibody AMAb90865 and the Anti-CTNNB1 rabbit polyclonal antibody HPA029159 were used for the Multiplexed IHC-IF staining of human colorectal cancer section showing membranous PLA reaction. Tonsil was used as negative control ( ). E-cadherin immunoreactivity in tumor cells (AMAb90865, magenta) and laminin gamma 1 B positivity in basement membranes (AMAb91138, green). Page 2 (4) The Epithelial to Mesenchymal The antibodies targeting selected EMT On the contrary, N-cadherin (CDH2) ex- Transition Marker Panel marker proteins are: pression is high in e.g. the nervous sys- tem (G and inset on J), heart muscle (H) Epithelial and mesenchymal cells are fun- • IHC-validated in relevant normal and and testis (I), while glandular epithelium of damentally different and represent the two cancer human tissues gastrointestinal tract (J, K) and squamous main cell types in the body. -

Human N-Cadherin / CD325 / CDH2 Protein (His & Fc Tag)

Human N-Cadherin / CD325 / CDH2 Protein (His & Fc Tag) Catalog Number: 11039-H03H General Information SDS-PAGE: Gene Name Synonym: CD325; CDHN; CDw325; NCAD Protein Construction: A DNA sequence encoding the human CDH2 (NP_001783.2) (Met 1-Ala 724) was fused with the C-terminal polyhistidine-tagged Fc region of human IgG1 at the C-terminus. Source: Human Expression Host: HEK293 Cells QC Testing Purity: > 70 % as determined by SDS-PAGE Endotoxin: Protein Description < 1.0 EU per μg of the protein as determined by the LAL method Cadherins are calcium dependent cell adhesion proteins, and they preferentially interact with themselves in a homophilic manner in Stability: connecting cells. Cadherin 2 (CDH2), also known as N-Cadherin (neuronal) (NCAD), is a single-pass tranmembrane protein and a cadherin containing ℃ Samples are stable for up to twelve months from date of receipt at -70 5 cadherin domains. N-Cadherin displays a ubiquitous expression pattern but with different expression levels between endocrine cell types. CDH2 Asp 160 Predicted N terminal: (NCAD) has been shown to play an essential role in normal neuronal Molecular Mass: development, which is implicated in an array of processes including neuronal differentiation and migration, and axon growth and fasciculation. The secreted recombinant human CDH2 is a disulfide-linked homodimeric In addition, N-Cadherin expression was upregulated in human HSC during protein. The reduced monomer comprises 813 amino acids and has a activation in culture, and function or expression blocking of N-Cadherin predicted molecular mass of 89.9 kDa. As a result of glycosylation, it promoted apoptosis. During apoptosis, N-Cadherin was cleaved into 20- migrates as an approximately 114 and 119 kDa band in SDS-PAGE under 100 kDa fragments. -

The N-Cadherin Interactome in Primary Cardiomyocytes As Defined Using Quantitative Proximity Proteomics Yang Li1,*, Chelsea D

© 2019. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2019) 132, jcs221606. doi:10.1242/jcs.221606 TOOLS AND RESOURCES The N-cadherin interactome in primary cardiomyocytes as defined using quantitative proximity proteomics Yang Li1,*, Chelsea D. Merkel1,*, Xuemei Zeng2, Jonathon A. Heier1, Pamela S. Cantrell2, Mai Sun2, Donna B. Stolz1, Simon C. Watkins1, Nathan A. Yates1,2,3 and Adam V. Kwiatkowski1,‡ ABSTRACT requires multiple adhesion, cytoskeletal and signaling proteins, The junctional complexes that couple cardiomyocytes must transmit and mutations in these proteins can cause cardiomyopathies (Ehler, the mechanical forces of contraction while maintaining adhesive 2018). However, the molecular composition of ICD junctional homeostasis. The adherens junction (AJ) connects the actomyosin complexes remains poorly defined. – networks of neighboring cardiomyocytes and is required for proper The core of the AJ is the cadherin catenin complex (Halbleib and heart function. Yet little is known about the molecular composition of the Nelson, 2006; Ratheesh and Yap, 2012). Classical cadherins are cardiomyocyte AJ or how it is organized to function under mechanical single-pass transmembrane proteins with an extracellular domain that load. Here, we define the architecture, dynamics and proteome of mediates calcium-dependent homotypic interactions. The adhesive the cardiomyocyte AJ. Mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes assemble properties of classical cadherins are driven by the recruitment of stable AJs along intercellular contacts with organizational and cytosolic catenin proteins to the cadherin tail, with p120-catenin β structural hallmarks similar to mature contacts. We combine (CTNND1) binding to the juxta-membrane domain and -catenin β quantitative mass spectrometry with proximity labeling to identify the (CTNNB1) binding to the distal part of the tail. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

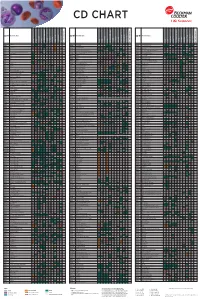

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Quantitation of the Number of Molecules of Glycophorins C and D on Normal Red Blood Cells Using Radioiodinatedfab Fragments of Monoclonal Antibodies

Quantitation of the Number of Molecules of Glycophorins C and D on Normal Red Blood Cells Using RadioiodinatedFab Fragments of Monoclonal Antibodies By Jon Smythe, Brigitte Gardner, andDavid J. Anstee Two rat monoclonal antibodies (BRAC 1 and BRAC 1 1 ) cytes. Fabfragments of BRAC 1 1 and ERIC 10 gave values have been produced. BRAC 1 recognizes an epitope com- of 143,000 molecules GPC per red blood cell (RBC). Fab mon to the human erythrocyte membrane glycoproteins fragments of BRAC1 gave 225,000 molecules of GPC and glycophorin C (GPC) and glycophorin D (GPD). BRAC 11 GPD per RBC. These results indicate that GPC and GPD is specific for GPC. Fabfragments of these antibodies and together are sufficiently abundantto provide membrane at- BRlC 10, a murine monoclonal anti-GPC,were radioiodin- tachment sites for all ofthe protein 4.1 in normal RBCs. ated and used in quantitative binding assays to measure 0 1994 by The American Societyof Hematology. the number of GPC and GPD molecules on normal erythro- HE SHAPE AND deformability of the mature human (200,000)" and those reported for GPC (50,000).7 This nu- Downloaded from http://ashpublications.org/blood/article-pdf/83/6/1668/612763/1668.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 T erythrocyte is controlled by a flexible two-dimensional merical differencehas led to the suggestion that a significant lattice of proteins, which together comprise the membrane proportion of protein 4.1 in normal erythrocyte membranes skeleton.' The major components of the skeleton are spec- must be bound to sites other than GPC and GPD.3 The trin, actin, ankyrin, and protein 4.1. -

And MUC1 in Mammary Epithelial Cells

Linköping University Post Print Loss of ICAM-1 signaling induces psoriasin (S100A7) and MUC1 in mammary epithelial cells Stina Petersson, E. Shubbar, M. Yhr, A. Kovacs and Charlotta Enerbäck N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com: Stina Petersson, E. Shubbar, M. Yhr, A. Kovacs and Charlotta Enerbäck, Loss of ICAM-1 signaling induces psoriasin (S100A7) and MUC1 in mammary epithelial cells, 2011, Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, (125), 1, 13-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-0820-4 Copyright: Springer Science Business Media http://www.springerlink.com/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-63954 1 Loss of ICAM-1 signaling induces psoriasin (S100A7) and MUC1 in mammary epithelial cells Petersson S1, Shubbar E1, Yhr M1, Kovacs A2 and Enerbäck C3 Departments of 1Clinical Genetics and 2Pathology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, SE-413 45 Gothenburg, Sweden; 3Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Division of Cell Biology and Dermatology, Linköping University, SE-581 85 Linköping, Sweden E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: maria.yhr@ clingen.gu.se E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Correspondence: Stina Petersson, Department of Clinical Genetics, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, SE-413 45 Gothenburg, Sweden E-mail: [email protected] 2 Abstract Psoriasin (S100A7), a member of the S100 gene family, is highly expressed in high-grade comedo ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), with a higher risk of local recurrence. Psoriasin is therefore a potential biomarker for DCIS with a poor prognosis. -

Syndecan-1 Depletion Has a Differential Impact on Hyaluronic Acid Metabolism and Tumor Cell Behavior in Luminal and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Syndecan-1 Depletion Has a Differential Impact on Hyaluronic Acid Metabolism and Tumor Cell Behavior in Luminal and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells Sofía Valla 1,2 , Nourhan Hassan 3 , Daiana Luján Vitale 2,4 , Daniela Madanes 5, Fiorella Mercedes Spinelli 2,4, Felipe C. O. B. Teixeira 3, Burkhard Greve 6 , Nancy Adriana Espinoza-Sánchez 3,6 , Carolina Cristina 1,2, Laura Alaniz 2,4,* and Martin Götte 3,* 1 Laboratorio de Fisiopatología de la Hipófisis, Centro de Investigaciones Básicas y Aplicadas (CIBA), Universidad Nacional del Noroeste de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (UNNOBA), Libertad 555, Junín (B6000), Buenos Aires 2700, Argentina; sofi[email protected] (S.V.); [email protected] (C.C.) 2 Centro de Investigaciones y Transferencia del Noroeste de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (CITNOBA, UNNOBA-UNSAdA-CONICET), Buenos Aires 2700, Argentina; [email protected] (D.L.V.); fi[email protected] (F.M.S.) 3 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Münster University Hospital, Domagkstrasse 11, 48149 Münster, Germany; [email protected] (N.H.); [email protected] (F.C.O.B.T.); [email protected] (N.A.E.-S.) 4 Laboratorio de Microambiente Tumoral, Centro de Investigaciones Básicas y Aplicadas (CIBA), Universidad Nacional del Noroeste de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (UNNOBA), Libertad 555, Junín (B6000), Citation: Valla, S.; Hassan, N.; Vitale, Buenos Aires 2700, Argentina 5 Laboratorio de Inmunología de la Reproducción, Instituto de Biología y Medicina Experimental—Consejo D.L.; Madanes, D.; Spinelli, F.M.; Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (IBYME-CONICET), Vuelta de Obligado 2490, Ciudad Teixeira, F.C.O.B.; Greve, B.; Autónoma de Buenos Aires (C1428ADN), Buenos Aires 2700, Argentina; [email protected] Espinoza-Sánchez, N.A.; Cristina, C.; 6 Department of Radiotherapy—Radiooncology, Münster University Hospital, Robert-Koch-Str. -

The CD44-Initiated Pathway of T-Cell Extravasation Uses VLA-4 but Not LFA-1 for Firm Adhesion

The CD44-initiated pathway of T-cell extravasation uses VLA-4 but not LFA-1 for firm adhesion Mark H. Siegelman, … , Diana Stanescu, Pila Estess J Clin Invest. 2000;105(5):683-691. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI8692. Article Leukocytes extravasate from the blood in response to physiologic or pathologic demands by means of complementary ligand interactions between leukocytes and endothelial cells. The multistep model of leukocyte extravasation involves an initial transient interaction (“rolling” adhesion), followed by secondary (firm) adhesion. We recently showed that binding of CD44 on activated T lymphocytes to endothelial hyaluronan (HA) mediates a primary adhesive interaction under shear stress, permitting extravasation at sites of inflammation. The mechanism for subsequent firm adhesion has not been elucidated. Here we demonstrate that the integrin VLA-4 is used in secondary adhesion after CD44-mediated primary adhesion of human and mouse T cells in vitro, and by mouse T cells in an in vivo model. We show that clonal cell lines and polyclonally activated normal T cells roll under physiologic shear forces on hyaluronate and require VCAM-1, but not ICAM-1, as ligand for subsequent firm adhesion. This firm adhesion is also VLA-4 dependent, as shown by antibody inhibition. Moreover, in vivo short-term homing experiments in a model dependent on CD44 and HA demonstrate that superantigen-activated T cells require VLA-4, but not LFA-1, for entry into an inflamed peritoneal site. Thus, extravasation of activated T cells initiated by CD44 binding to HA depends upon VLA-4–mediated firm adhesion, which may explain the frequent association of these adhesion receptors with diverse chronic inflammatory processes.