3/17/14 1 a Railroad Runs Through It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jniversity of Minnesota Northrop Memorial Auditorium 970 Cap and Gown Day Convocation .Hursday, May 14, 1970 at Eleven -Fifteen O'clock

IVERSITY OF MINNESOTA NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM I JNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM 970 CAP AND GOWN DAY CONVOCATION .HURSDAY, MAY 14, 1970 AT ELEVEN -FIFTEEN O'CLOCK TABLE OF CONTENTS The Cap and Gown Tradition ..... 1 Board of Regents and . Administrative Officers ... :..... ............ 2 Scholarships, Fellowships, Awards, and Prizes . .. .. .... .. 3 Student With Averages of B or Higher ............ ..... ................ ... .. , . 121 Academic Costume .. _ .. ....... 159 Order of events THE PROCESSIONAL The Frances Millet· Brown Memorial Bells, played by Janet Orjala, CLA '70, will be ·heard from Northrop Memorial Auditorium before the procession begins. The University of M-innesota Conce1t Band, Symphony Band I, and Symphony Band ll, conducted by Assistant Director of Band Fredrick Nyline, will play from the steps of Northrop Auditorium during the procession. The academic procession from the lower Mall into the Auditorium will be led by the Mace-Bearer, Professor James R. Jensen, D.D.S., M.S., Assistant Dean for Academic Affairs, School of Dentishy Following the Mace-Bearer will be candidates for degrees, ~arching by college, other honor students, the faculty, and the President. In the Auditorium, the audience is asked to remain seated so that all can see the procession. As the Mace-Bearer enters the Auditorium, Professor of Music ·and University Organist Heinrich Fleischer, Ph.D., will play the processional. The Mace-Bearer will present the Mace at the center of the stage. Candidates .for degrees will take places on 'either side of the middle aisle. Other honor students, includ ing freshman through graduate students, will be seated next to the candidates for degrees. When faculty members, marching last, have assembled on stage, the Mace-Bearer will place ·the Mace in its cradle, signaling the beginning of the ceremony. -

Summer Session

General Studio Policies Mission Statement Tuition We are dedicated to share the love of dance Tuition is payable by the first class. 160 Tyler Road N, Box 11 with students, to develop pride and confidence in self Red Wing, MN 55066 Competition Students and to help students grow and develop to the best of 6513859389 Competition students have requirements for their abilities with dance and within themselves. [email protected] summer dance. Please refer to the handout for requirements for each team. Inform the studio We will commit ourselves to in writing if you are unable to attend required quality instruction and excellence in dance. classes and also submit your plan for classes to take to make up the summer requirements. Summer Session Dance Dress Code Ballet Intensive June 17 – 20 Any color or style of leotards and tights, unitard, Studio Etiquette & Rules or dance clothing may be worn to most classes. Technique Intensive Boys may wear shorts and a t-shirt. Hip-hop RESPECT OTHERS. July 8 - 11 dress may be more casual wear. No loose Please arrive for class ready and on July 15 – 18 clothing. time. July 22 – 25 Dress code in ballet intensive classes must be Dress codes must be followed. pink ballet shoes, pink tights, black leotard, and Workshop July 27 no jewelry. Hair must be in a bun with a hairnet Label all shoes, equipment, and around the bun. In ballet class, boys wear shorts sportswear with name. Auditions July 28 (above the knee) and a tank shirt. This dress code allows the instructors to see body lines to Food and drink must be kept in the help with corrections and to prevent injury. -

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities Combined Heat and Power Project

001 p-bp15-01-02a 002 003 004 005 MINNESOTA POLLUTION CONTROL AGENCY RMAD and Industrial Divisions Environment & Energy Section; Air Quality Permits Section The University of Minnesota Twin Cities Combined Heat and Power Project (1) Request for Approval of Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order and Authorization to Issue a Negative Declaration on the Need for an Environmental Impact Statement; and (2) Request for Approval of Findings of Fact, Conclusion of Law, and Order, and Authorization to Issue Permit No. 05301050 -007. January 27, 2015 ISSUE STATEMENT This Board Item involves two related, but separate, Citizens’ Board (Board) decisions: (1) Whether to approve a Negative Declaration on the need for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed University of Minnesota Twin Cities Campus Combined Heat and Power Project (Project). (2) If the Board approves a Negative Declaration on the need for an EIS, decide whether to authorize the issuance of an air permit for the Project. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) staff requests that the Board approve a Negative Declaration on the need for an EIS for the Project and approve the Findings of Fact, Conclusion of Law, and Order supporting the Negative Declaration. MPCA staff also requests that the Board approve the Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order authorizing the issuance of Air Emissions Permit No. 05301050-007. Project Description. The University of Minnesota (University) proposes to construct a 22.8 megawatt (MW) combustion turbine generator with a 210 million British thermal units (MMBTU)/hr duct burner to produce steam for the Twin Cities campus. -

7-12 BOR Docket Sheet

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BOARD OF REGENTS Wednesday, July 11, 2012 1:15 - 2:45 p.m. 600 McNamara Alumni Center, Boardroom Board Members Linda Cohen, Chair David Larson, Vice Chair Clyde Allen Richard Beeson Laura Brod Thomas Devine John Frobenius Venora Hung Dean Johnson David McMillan Maureen Ramirez Patricia Simmons AGENDA 1. Introductions - E. Kaler (pp. 3-7) A. Chancellor, University of Minnesota Crookston B. Athletic Director, Twin Cities Campus C. Faculty Consultative Committee Chair D. Academic Professionals & Administrators Consultative Committee Chair E. Civil Service Consultative Committee Chair 2. Approval of Minutes - Action - L. Cohen 3. Report of the President - E. Kaler 4. Report of the Chair - L. Cohen 5. Election of Secretary & Appointment of Executive Director - Review/Action - L. Cohen (pp. 8-16) 6. Receive and File Reports (pp. 17-19) A. Board of Regents Policy Report 7. Consent Report - Review/Action - L. Cohen (pp. 20-34) A. Gifts B. Educational Planning & Policy Committee Consent Report 8. Board of Regents Policy: Institutional Conflict of Interest - Action - M. Rotenberg/A. Phenix (pp. 35-38) 9. Board of Regents Policy: Employee Compensation and Recognition - Review/Action - K. Brown/ A. Phenix (pp. 39-42) 10. Board of Regents Policy: Employee Development, Education, and Training - Review/Action - K. Brown/A. Phenix (pp. 43-46) 11. Resolution Related to: Alcoholic Beverage Sales at TCF Bank Stadium, Mariucci Arena, and Williams Arena - Review/Action - A. Phenix/W. Donohue (pp. 47-50) 12. Itasca Project Higher Education Task Force - Partnerships for Prosperity - E. Kaler/G. Page (pp. 51-52) 13. Report of the Faculty, Staff & Student Affairs Committee - P. -

Minnesota Citizens for the Arts

MINNESOTA Vote Citizens for the Arts Legislative Candidate Survey 2016 smART! The election on November 8, 2016 will have a huge impact on the arts and on our country. If you agree with thousands of Minnesotans who believe that the arts matter, you’ll want to know where legislators stand. IMPORTANT: Visit the Secretary of State’s website to fnd out your district and where to vote: http://pollfnder.sos.state.mn.us/ READ: We’ve asked all legislative candidates fve questions about current arts issues so they can tell you how they would vote. Due to limited space, comments were limited to 3 sentences. To see full responses visit our website at www.artsmn.org ALL STARS: Look for the symbol telling you which legislators have been awarded an Arts All Star from MCA for their exceptional support for the arts at the legislature! CONNECT: With MCA on Facebook, Twitter @MNCitizen, and our website www.artsmn.org. We’ll make sure you stay informed. ASK: If your candidates didn’t respond to the survey, make sure to ask them these questions when you see them on the campaign trail! ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★ ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★ Minnesota Citizens for the Arts is a non-partisan statewide arts advocacy organization whose mission is to ensure the opportunity for all people to have access to and involvement in the arts. MCA organizes the arts com- munity and lobbies the Minnesota State Legislature and U.S. Congress on issues pertaining to the nonproft arts. MCA does not endorse candidates for public ofce. MCA’s successes include passing the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment in 2008 which created dedi- cated funding for the arts in the Minnesota State Constitution for the next 25 years, and the Creative Minnesota research project at CreativeMN.org. -

Accessible Arts Calendar Summary 2019 Current Venues and Shows

Accessible Arts Calendar Summary 2019 Current Venues and Shows Updated 9-4-19 – The VSA Minnesota Accessible Arts Calendar lists arts events that proactively offer accessibility accommodations such as: ASL (American Sign Language Interpreting), AD (Audio Description), CC (Closed Captioning), OC (Open or Scripted Captioning), DIS (performers with disabilities), or SENS (Sensory-friendly accommodations) which are inclusive for children on the autism spectrum. The main Accessible Arts Calendar listings (emailed monthly through August 2019 and online at http://vsamn.org/community/calendar) offer descriptions of shows, authors, directors, describer & interpreter names, ticket prices, discounts, dates for Pay What You Can (PWYC), and more. This Current Venues and Shows list supplements the Accessible Arts Calendar. On our website as a Resource under Community (http://vsamn.org/community/resources-community/), it summarizes shows at arts venues across Minnesota: plays, concerts, exhibits, films, storytelling, etc. It’s limited to what we learn about and have time to include. The venues are organized alphabetically by Twin Cities venues and then by Greater Minnesota venues. They may offer accessible performances proactively or upon request. Words in GREEN identify some accessibility accommodations. We assume all auditoriums and bathrooms are wheelchair-accessible and theatres with fixed seating have assistive listening devices, unless noted otherwise. Both calendars will be discontinued after September 2019 when VSA Minnesota ceases operation. -

BUILDING U.S.-CHINA BRIDGES China Center Annual Report 2007-08 Inside from the Director

BUILDING U.S.-CHINA BRIDGES China Center Annual Report 2007-08 Inside From the Director........................................................... 1 Students and Scholars .................................................... 2 Faculty ............................................................................ 3 K-12 Initiatives .............................................................. 4 Training Programs .......................................................... 5 Griffin Lecture ................................................................ 6 Community Engagement ............................................... 7 Recruitment .................................................................... 8 To Our Chinese Friends ................................................. 9 Bridging Relationships ................................................. 10 Contributors ................................................................. 11 Corporate Partnership / Budget .................................... 12 CCAC and China Center Office Information ............... 13 Note about Chinese names: The China Center’s policy is to print an individual’s name according to the custom of the place where they live (e.g., family name first for a person who lives in China). On the Cover 1 1. A Bridge in China 2 3 2. China Center Dragon Boat team (page 7) 3. Participants in the First Sino-US Education Forum (page 3) 4 4. Students in Northrop Auditorium for China Day (page 4) 5. Training program participants at their graduation reception (page 5) 5 6 6. Training -

September 4, 2014 Kansas City Ballet New Artistic Staff and Company

Devon Carney, Artistic Director FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ellen McDonald 816.444.0052 [email protected] For Tickets: 816.931.2232 or www.kcballet.org Kansas City Ballet Announces New Artistic Staff and Company Members Grace Holmes Appointed New School Director, Kristi Capps Joins KCB as New Ballet Master, and Anthony Krutzkamp is New Manager for KCB II Eleven Additions to Company, Four to KCB II and Creation of New Trainee Program with five members Company Now Stands at 29 Members KANSAS CITY, MO (Sept. 4, 2014) — Kansas City Ballet Artistic Director Devon Carney today announced the appointment of three new members of the artistic staff: Grace Holmes as the new Director of Kansas City Ballet School, Kristi Capps as the new Ballet Master and Anthony Krutzkamp as newly created position of Manager of KCB II. Carney also announced eleven new members of the Company, increasing the Company from 28 to 29 members for the 2014-2015 season. He also announced the appointment of four new KCB II dancers, which stands at six members. Carney also announced the creation of a Trainee Program with five students, two selected from Kansas City Ballet School. High resolution photos can be downloaded here. Carney stated, “With the support of the community, we were able to develop and grow the Company as well as expand the scope of our training programs. We are pleased to welcome these exceptional dancers to Kansas City Ballet and Kansas City. I know our audiences will enjoy the talent and diversity that these artists will add to our existing roster of highly professional world class performers that grace our stage throughout the season ahead. -

Sheila Smith, 651-251-0868 Executive Director, Minnesota Citizens for the Arts Kathy Mouacheupao, 651-645-0402 Executive Director, Metropolitan Regional Arts Council

3/12/19 Contacts: Sheila SMith, 651-251-0868 Executive Director, Minnesota Citizens for the Arts Kathy Mouacheupao, 651-645-0402 Executive Director, Metropolitan Regional Arts Council Creative Minnesota 2019 Study Reveals Growth of Arts and Culture Sector in Twin Cities Metropolitan Area Minnesota SAINT PAUL, MN: Creative Minnesota, Minnesota Citizens for the Arts and the Metropolitan Regional Arts Council released a new study today indicating that the arts and culture sector in Twin Cities Metropolitan Area is groWing. “The passage of the Legacy AMendment in Minnesota allowed the Metropolitan Regional Arts Council and Minnesota State Arts Board to increase support for the arts and culture in this area, and that has had a big iMpact,” said Sheila SMith, Executive Director of Minnesota Citizens for the Arts. “It’s wonderful to see how the access to the arts has groWn in this area over tiMe.” The Legacy Amendment was passed by a statewide vote of the people of Minnesota in 2008 and created dedicated funding for the arts and culture in Minnesota. The legislature appropriates the dollars from the Legacy Arts and Culture Fund to the Minnesota State Arts Board, Regional Arts Councils, Minnesota Historical Society and other entities to provide access to the arts and culture for all Minnesotans. “Creative Minnesota’s new 2019 report is about Minnesota’s arts and creative sector. It includes stateWide, regional and local looks at nonprofit arts and culture organizations, their audiences, artists and creative Workers. This year it also looks at the availability of arts education in Minnesota schools,” said SMith. “We also include the results of fifteen local studies that show substantial economic iMpact from the nonprofit arts and culture sector in every corner of the state, including $4.9 million in the City of Eagan, $2.4 million in the City of Hastings, 11 million in the City of Hopkins, $4 million in the Maple Grove Area, $541 million in the City of Minneapolis, and $1.5 million in the City St. -

Without a Concerted Effort, Our State's Historic and Cultural Treasures Are in Danger of Being Lost to Time. the Minnesota

Without a concerted effort, our state’s historic and cultural treasures are in danger of being lost to time. The Minnesota Historical Society awarded a Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grant in the amount of $7,000 to the City of Mankato. The grant was approved by the Society’s awards committee on July 22, 2010 and will support its Historic Survey of 12 Properties for Local Designation Project. Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants are made possible by the Minnesota Legislature from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund created with passage of the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment to the Minnesota Constitution in November 2008. The grants are awarded to support projects of enduring value for the cause of history and historic preservation across the state. Historic Survey of 12 Properties for Local Designation Project The Historic Survey of 12 Properties for Local Designation Project is a project of enduring value because it will provide a list of properties to be listed on Mankato’s Local Historic Registry. The project begins on October 1, 2010 with an anticipated completion date of February 1, 2011. The project will include conducting historic surveys on 12 properties for potential local designation. “It is wonderful to see so many communities and local organizations benefitting from the Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants,” said Britta Bloomberg, deputy state historic preservation officer. “Minnesotans should be proud of the unprecedented opportunities these grants provide for organizations to preserve and share our history and cultural heritage. The impact of projects supported by Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants will be felt throughout the state for many years to come.” City of Mankato Historic Properties Survey and Local Designation Inventory Form Report Prepared for the City of Mankato Heritage Preservation Commission Prepared by Thomas R. -

Feld Ballets/NY

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Feld Ballets/NY WEDNESDAY & THURSDAY, APRIL 4 & 5, 1990, AT 8:00 P.M. POWER CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN The Company Lynn Aaron Nina Goldman Scott Rink Mucuy Bolles Patrice Hemsworth Joseph Rodgers David M. Cohen Terace E. Jones Jennita Russo Allison Wade Cooper Joseph Marshall James Sewell Geralyn DelCorso Priscila Mesquita Elizabeth Simonson Judith Denman Buffy Miller Lisa Street Darren Gibson Jeffrey Neeck Joan Tsao PETER LONGIARU, Company Pianist ALLEN LEE HUGHES, Resident Lighting Designer CORA CAHAN, Executive Director PETER HAUSER, Production Manager Feld Ballets/NY wishes to thank the following supporters who have helped to make these performances possible: Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Fund Mary Flagler Gary Charitable Trust Live Music for Opera and Dance; Robert Sterling Clark Foundation Inc.; The Eleanor Naylor Dana Charitable Trust; The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; National Corporate Fund for Dance, Inc.; The Scherman Foundation, Inc.; Joan C. Schwartz Philanthropic Fund; the Emma A. Sheafer Charitable Trust; and The Shubert Organization. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. This project is supported by the Michigan Council for the Arts, and by Arts Midwest members and friends in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts. The University Musical Society is an Equal Opportunity Employer and provides services without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, age, sex, or handicap. 38th and 39th Concerts of the lllth Season Nineteenth Annual Choice Series PROGRAM Wednesday, April 4 CONTRA POSE (1990) Choreography: Eliot Feld Music: C. -

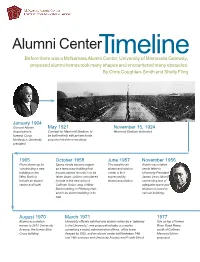

Alumni Center

Alumni CenterTimeline Before there was a McNamara Alumni Center, University of Minnesota Gateway, proposed alumni homes took many shapes and encountered many obstacles. By Chris Coughlan-Smith and Shelly Fling January 1904 General Alumni May 1921 November 15, 1924 Association is Concept for Memorial Stadium, to Memorial Stadium dedicated formed; Cyrus be built entirely with private funds, Northrop is University proposed at alumni meetings president 1965 October 1958 June 1957 November 1956 Plans drawn up for Space needs become urgent The need for an Alumni association constructing a new as a temporary building that alumni and visitors sends letter to building on the houses alumni records is to be center is first University President West Bank to taken down; options considered expressed by James Lewis Morrill include an alumni include in the new wing of alumni association concerning lack of center and hotel Coffman Union; atop a West adequate space and Bank building; in Pillsbury Hall; divisions housed in and in an alumni building of its various buildings own August 1970 March 1971 1977 Alumni association University officials ask that any alumni center be a “gateway Site on top of former moves to 2610 University to the University”; one proposal includes a complex River Road Ramp Avenue, the former Blue containing a motel, administrative offices, office tower south of Coffman Cross building (leased by IDS), and an alumni center built between 14th Memorial Union and 16th avenues and University Avenue and Fourth Street proposed 1979 Alumni association offices move to Morrill Hall, lessening the immediate need for office space 1980 Leonard Parker and Associates completes a drawing of a proposed alumni center; the projected cost of a site on the river is $4 million; University officials agree with alumni center Timeline idea but disagree over the site and on parking issues September 1981 Gopher football team moves to the new Hubert H.