Mapping Community Assets, Needs & Networks in East Walworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vision for Social Housing

Building for our future A vision for social housing The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing Building for our future: a vision for social housing 2 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Contents Contents The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing For more information on the research that 2 Foreword informs this report, 4 Our commissioners see: Shelter.org.uk/ socialhousing 6 Executive summary Chapter 1 The housing crisis Chapter 2 How have we got here? Some names have been 16 The Grenfell Tower fire: p22 p46 changed to protect the the background to the commission identity of individuals Chapter 1 22 The housing crisis Chapter 2 46 How have we got here? Chapter 3 56 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 3 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 4 The consequences of the decline p56 p70 Chapter 4 70 The consequences of the decline Chapter 5 86 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 90 Reforming social renting Chapter 7 Chapter 5 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 Reforming social renting 102 Reforming private renting p86 p90 Chapter 8 112 Building more social housing Recommendations 138 Recommendations Chapter 7 Reforming private renting Chapter 8 Building more social housing Recommendations p102 p112 p138 4 Building for our future: a vision for social housing 5 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Foreword Foreword Foreword Reverend Dr Mike Long, Chair of the commission In January 2018, the housing and homelessness charity For social housing to work as it should, a broad political Shelter brought together sixteen commissioners from consensus is needed. -

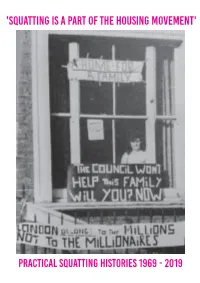

'Squatting Is a Part of the Housing Movement'

'Squatting Is A Part OF The HousinG Movement' PRACTICAL SQUATTING HISTORIES 1969 - 2019 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘...I learned how to crack window panes with a hammer muffled in a sock and then to undo the catch inside. Most houses were uninhabit- able, for they had already been dis- embowelled by the Council. The gas and electricity were disconnected, the toilets smashed...Finally we found a house near King’s Cross. It was a disused laundry, rather cramped and with a shopfront window...That night we changed the lock. Next day, we moved in. In the weeks that followed, the other derelict houses came to life as squatting spread. All the way up Caledonian Road corrugated iron was stripped from doors and windows; fresh paint appeared, and cats, flow- erpots, and bicycles; roughly printed posters offered housing advice and free pregnancy testing...’ Sidey Palenyendi and her daughters outside their new squatted home in June Guthrie, a character in the novel Finsbury Park, housed through the ‘Every Move You Make’, actions of Haringey Family Squatting Association, 1973 Alison Fell, 1984 Front Cover: 18th January 1969, Maggie O’Shannon & her two children squatted 7 Camelford Rd, Notting Hill. After 6 weeks she received a rent book! Maggie said ‘They might call me a troublemaker. Ok, if they do, I’m a trouble maker by fighting FOR the rights of the people...’ 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘Some want to continue living ‘normal lives,’ others to live ‘alternative’ lives, others to use squatting as a base for political action. -

Name Location Opening Time Cost Additional Info Area Link East Street

Public Toilets in Southwark Council Key Restroom Baby Change Disabled toilet Changing Places Toilet Name Location Opening Time Facilities Cost Additional info Area Link Monday: Closed Jct. with Portland Street Tuesday to Saturday: http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e East Street Market Free Bankside and Walworth SE17 07:00 to 16:00 nvironment/public-toilets Sunday: 07:00 to 16:00 Monday to Friday 9am to 7pm; 211 Borough High Street http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e John Harvard Library Saturday 9am to 5pm; Sunday 12 Free Bankside and Walworth SE1 1JA nvironment/public-toilets noon to 4pm Burgess Park BMX track, http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e Burgess Park Burgess Park, Albany Every day; 9am to 9pm Free Bankside and Walworth nvironment/public-toilets Road, SE5 0RJ Burgess Park, Tennis http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e Burgess Park Every day; 9am to 9pm Free Bankside and Walworth court, SE5 0RJ nvironment/public-toilets Page 1 of 9 Public Toilets in Southwark Council Key Restroom Baby Change Disabled toilet Changing Places Toilet Name Location Opening Time Facilities Cost Additional info Area Link Chumleigh Gardens, http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e Burgess Park Burgess Park, Chumleigh Daily: 9am to 5pm Free Bankside and Walworth nvironment/public-toilets Street, SE5 0RJ Open Daily at 8am. rear of Cobourg primary http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e Burgess Park Lake Closing times vary throughout the Free Bankside and Walworth School nvironment/public-toilets year Geraldine Mary attached to kiosk, 91 St http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e Daily: 10am to 6pm Free Located at the café Bankside and Walworth Harmsworth Park George's Road, SE1 6ER nvironment/public-toilets Monday to Friday: 06:30 to 22:00, The Castle Leisure 2 St Gabriel Walk, Saturday: 07:00 to 18:00, http://www.southwark.gov.uk/e Free Bankside and Walworth Centre London, SE1 6FG Sunday: 07:00 to 22:00. -

New Southwark Plan Preferred Option: Area Visions and Site Allocations

NEW SOUTHWARK PLAN PREFERRED OPTION - AREA VISIONS AND SITE ALLOCATIONS February 2017 www.southwark.gov.uk/fairerfuture Foreword 5 1. Purpose of the Plan 6 2. Preparation of the New Southwark Plan 7 3. Southwark Planning Documents 8 4. Introduction to Area Visions and Site Allocations 9 5. Bankside and The Borough 12 5.1. Bankside and The Borough Area Vision 12 5.2. Bankside and the Borough Area Vision Map 13 5.3. Bankside and The Borough Sites 14 6. Bermondsey 36 6.1. Bermondsey Area Vision 36 6.2. Bermondsey Area Vision Map 37 6.3. Bermondsey Sites 38 7. Blackfriars Road 54 7.1. Blackfriars Road Area Vision 54 7.2. Blackfriars Road Area Vision Map 55 7.3. Blackfriars Road Sites 56 8. Camberwell 87 8.1. Camberwell Area Vision 87 8.2. Camberwell Area Vision Map 88 8.3. Camberwell Sites 89 9. Dulwich 126 9.1. Dulwich Area Vision 126 9.2. Dulwich Area Vision Map 127 9.3. Dulwich Sites 128 10. East Dulwich 135 10.1. East Dulwich Area Vision 135 10.2. East Dulwich Area Vision Map 136 10.3. East Dulwich Sites 137 11. Elephant and Castle 150 11.1. Elephant and Castle Area Vision 150 11.2. Elephant and Castle Area Vision Map 151 11.3. Elephant and Castle Sites 152 3 New Southwark Plan Preferred Option 12. Herne Hill and North Dulwich 180 12.1. Herne Hill and North Dulwich Area Vision 180 12.2. Herne Hill and North Dulwich Area Vision Map 181 12.3. Herne Hill and North Dulwich Sites 182 13. -

Annex E2 Visit Reports.Pdf

Annex E2 Final Report Working Group 1 – Engineers WG1: Report on visit to the Ledbury Estate, Peckham, Southwark November 30th 2018. The Ledbury Estate is in Peckham and includes four 14-storey Large Panel System (LPS) tower blocks. The estate belongs to Southwark Council. The buildings were built for the GLC between 1968 and 1970. The dates of construction as listed as Bromyard (1968), Sarnsfield (1969), Skenfrith (1969) and Peterchurch House (1970). The WG1 group visited Peterchurch House on November 30th 2018. The WG1 group was met by Tony Hunter, Head of Engineering, and, Stuart Davis, Director of Asset Management and Mike Tyrrell, Director of the Ledbury Estate. The Ledbury website https://www.southwark.gov.uk/housing/safety-in-the-home/fire-safety-on-the- ledbury-estate?chapter=2 includes the latest Fire Risk Assessments, the Arup Structural Reports and various Residents Voice documents. This allowed us a good understanding of the site situation before the visit. In addition, Tony Hunter sent us copies of various standard regulatory reports. Southwark use Rowanwood Apex Asset Management System to manage their regulatory and ppm work. Following the Structural Surveys carried out by Arup in November 2017 which advised that the tower construction was not adequate to withstand a gas explosion, all piped gas was removed from the Ledbury Estate and a distributed heat system installed with Heat Interface Units (HIU) in each flat. Currently fed by an external boiler system. A tour of Peterchurch House was made including a visit to an empty flat where the Arup investigation points could be seen. -

The Summer Edition of the Castle Chronicle!

SUMMER EDITION Welcome to the Summer Edition of Castle Chronicle, for the Elephant and Castle community WELCOME TO THE SUMMER EDITION OF THE CASTLE CHRONICLE! In this edition, you will find interviews with traders year for a decade and then approximately 2,000 in Elephant and Castle, as well as updates on what full-time jobs in the new town centre. is going on around town. We are also taking this In the last few months the Elephant and Castle opportunity to celebrate our lockdown heroes, Town Centre Project Team, also submitted a minor the amazing people who have helped others amendments planning application, to increase the through the worst months of the pandemic. size of the London Underground station box to ENTERTAINMENT ON CASTLE SQUARE It has been a busy period for the Elephant and safeguard for an integrated underground station Castle Town Centre Project Team, with demolition should the Bakerloo Line extension come forward To all of our local lockdown heroes, we say thank well underway on site. These works will enable in the future. We are pleased to say this has been DIANA BARRANCO you. Our community has always been a place us to get started on building a new and improved approved by Southwark Council and a further minor where we take care of each other, and during town centre. When the Elephant and Castle Town amendment application has now been submitted for the pandemic we needed our family, friends and Centre is complete, there will be new homes, shops, further enhancements to the Town Centre scheme. -

TALL BUILDINGS BACKGROUND PAPER 1 1.2 Scope of Background Paper This Paper Covers the Entirety of the London Borough of Southwark, As Seen in Figure 2

NEW SOUTHWARK PLAN BACKGROUND PAPER TALL BUILDINGS JUNE 2020 Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 1.1 Purpose of Background Paper 1 1.2 Area Scope 2 1.3 Approach to Tall Buildings 3 1.4 Tall Buildings Definition 3 1.5 Areas Identified as most appropriate for tall buildings 3 2 Current Policy Context 5 2.1 National Planning Policy and Guidance 5 2.1.1 National Planning Policy Framework 2019 5 2.1.2 Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government National Design Guide 2019 5 2.2.3 Historic England Advice Note 4 2015 and Draft 2020 6 2.2 Regional Planning Policy and Guidance 6 2.2.1 London Plan 2016 and Emerging London Plan 2019 6 2.2.2 London View Management Framework (LVMF) Supplementary Planning Guidance 2012 6 3.8 Evolution of Southwark’s Local Plan Tall Building Strategy 7 3 Existing Context of Tall Buildings 8 3.1 Tall Buildings in London Borough of Southwark 8 3.2 Tall Buildings in Surrounding Area 10 4 Analysis: Most Appropriate Locations for Tall Buildings 12 4.1 Proximity to Existing Major Transport Nodes 12 4.2 Gateways, junctions of major roads, town centres and points of civic or local significance 14 4.3 Potential for New Open Space and Public Realm 15 4.4 Focus for Regeneration and New Large Scale Development and Investment 15 5 Analysis: Considerations for Tall Buildings 19 5.1 Topography 19 5.2 Borough Views 19 5.3 Strategic Views 21 5.4 Settings and Views of World Heritage Sites 22 5.5 Settings and Views of Heritage Assets 22 5.5.1 Conservation Areas 22 5.5.2 Listed Buildings 24 5.6 Thames Policy Area 24 5.7 Historic Parks -

Town and Country Planning Act 1990 Appeal Under Section 78 by Emery Planning on Behalf of Glennmark Trading Ltd

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 APPEAL UNDER SECTION 78 BY EMERY PLANNING ON BEHALF OF GLENNMARK TRADING LTD. HIGH PEAK REFERENCE: HPK/2015/0471 PLANNING INSPECTORATE REFERENCE: APP/H1033/W/16/3155484 PROOF OF EVIDENCE OF MELISSA KURIHARA MLPM, MRTPI 1 Proof of Evidence on behalf of High Peak Borough Council Brown Edge Road, Buxton Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Planning Policy 4 3. The Case for High Peak Borough Council 9 4. Conclusions 19 Appendix 1: Appeal decision Land off Craythorne Road, Stretton APP/B3410/W/15/3134848 Appendix 2: Appeal decision Land between Ashflats & A449, Mosspit, Stafford APP/Y3425/A/14/2217578 Appendix 3: Appeal decision Land bounded by Gresty Lane, Crewe APP/R0660/A/13/2209335 Appendix 4: Deliverable supply tables (large sites and allocations) Appendix 5: Proof of Evidence of A G Massie APP/H1033/W/16/3147726 Appendix 6: Rebuttal Proof of Evidence of A G Massie APP/H1033/W/16/3147726 2 1. Introduction 1.1. This Proof of Evidence has been prepared by Melissa Kurihara, Principal Planning Consultant at Urban Vision Partnership Ltd, a multi disciplinary planning consultancy based in Salford. 1.2. I am a chartered town planner with significant professional experience in housing land supply. I hold a Masters in Landscape, Planning and Management from University of Manchester and I am a member of the Royal Town Planning Institute. Prior to joining Urban Vision I worked in various planning policy teams within local government. 1.3. I have experience of all stages in Local Plan production from initial evidence gathering and the establishment of the correct OAN, through to submission, independent examination and adoption. -

Appendix 1 - Selection Criteria

Appendix 1 - Selection Criteria ILRE Phase 2 Review Criteria Cross-cutting points A clear understanding of local issues, needs, and demand both from a community and business perspective A rationale for the proposed project - why it is appropriate for the area? How much does a project bring an innovative or creative approach in its design or activities? The need to invest in more than shop fronts - looking at parades, the business, activity and events and the surrounding environment. Have we invested in this area before? If so, why this is a project in this area an improvement? What are the potential outputs and outcomes? The following 5 criteria should be used to analyse, challenge and score an area for potential investment ILRE funds and delivery of a specific package of works: 1. Alignment to existing regeneration programmes • Does the location lie in close proximity to existing regeneration programmes, activities or policy areas (e.g. OAPF, Protected Shopping Frontage)? - If it does, how strongly would a project in this area complement existing regeneration? - If it does not, what are the benefits and opportunities of investing here? • Can the benefits of the existing regeneration programme be extended to smaller retail environments on the fringes of the programme area? • How can investment protect and add value to these parades? • Would the project here increase the ability to attract additional funding streams 2. Local Economy Sustainability and Benefits • Can a project’s activities benefit a number of local groups and businesses or add value to existing activities in the area? • Can a project’s outputs continue to bring benefits to local retail groups or collectives after the funding has been spent? • Will the investment create new local employment opportunities • Will the investment result in or have the potential encourage local cottage and creative industries or new business start ups? • What is the likely impact of a project in this area helping to generate ongoing activities in the longer term? 3. -

Associate Contemporary Art Galleries, Project and Exhibition Spaces

Southwark Tate Borough Modern Market 15 Southwark St London Bridge The City JERWOOD Shard Hall SPACE St. Thomas St Tooley St Tower Southwark Bridge Rd Bridge Union St Union St Rotherhithe 14 Tunnel Copperfield St Marshalsea Rd Newcomen St Borough High St Bermondsey St Snowsfields FASHION AND TEXTILE MUSEUM 13 Great Suffolk St WHITE CUBE Tooley St 7 Borough 12 47/343/381 Webber St 18 Druid St Weston St 5 George Row George Chambers st Long Lane Leathermarket St Rotherhithe Tanner St Tanner St Maltby St CECILIA BRUNSON Park Trinity St Great Dover St / A2 Maltby St PROJECTS Tower Bridge Rd Royal Oak Yd Market 24 (Sat & Sun) Borough Rd 11 6 Old Jamaica Rd Harper Rd 20 VITRINE MATT’S GALLERY Jamaica Rd 47/188/381/C10/P12 Canada Decima StC10 Water 1 C10/47/231/188 Drummond Rd London Rd Abbey St Enid St St James’s Rd 25 Neckinger Southwark Park Rd Bermondsey Bermondsey Newington Causeway Law St Lower Rd Square 10 Grange Walk St George’s Rd Grange Rd Southwark Park 42/47/78/ 21 ART HOUSE1 188/343/381 Rouel Rd 8 2 Spa Falmouth Rd 19 Spa Rd Webster Rd Terminus Lucey Rd Clements Rd Elephant & Castle Tower Bridge Rd 1/78 Bermondsey Spa Gardens Bricklayers Crimscott St Yalding Rd Arms New Kent Rd TANNERY PROJECTS COLEMAN 53/63/168/172 363/453/415 PROJECT SPACE Page’s Walk DRAWING ROOM CGP LONDON 21/42 Chatham St Curtis St Willow Walk Southwark Park Rd Surrey Quays Heygate St Galleywall Rd Mandela Way Walworth Rd Raymouth Rd Balaclava Rd Reverdy Rd Monnow Rd St James’s Rd Flint St Dunton Rd 3 Old Kent Rd Lynton Rd Kennington Park Rd Penton Pl ASC GALLERY -

Southwark Council Ledbury Estate Structural Robustness Assessment for Large Panel System Tower Blocks with Piped Gas

Southwark Council Ledbury Estate Structural Robustness Assessment for Large Panel System Tower Blocks with Piped Gas Issue 2 | 30 August 2017 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 245112-05 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd 13 Fitzroy Street London W1T 4BQ United Kingdom www.arup.com Southwark Council Ledbury Estate Structural Robustness Assessment for Large Panel System Tower Blocks with Piped Gas Contents Page 1 Introduction and Brief 1 2 The Buildings 3 2.1 Description of Building 3 2.2 History of Ledbury Estate and LPS buildings 5 3 Investigations 7 3.1 Description of investigations 7 3.2 Findings of investigations 8 3.3 Limitations of investigations 17 4 Assessment 18 4.1 Assessment Criteria 18 4.2 Assessment Discussion 19 5 Future actions 23 6 Conclusions 24 7 References 25 Appendix A TWA buildings with ‘Type B’ H2 Joint | Issue 2 | 30 August 2017 1 Introduction and Brief In July 2017, Arup was appointed by Southwark Council to carry out a visual investigation into the structure of four tower blocks on the Ledbury Estate, after residents reported cracks appearing in the ceilings, floor and walls. This investigation concluded that these cracks were gaps between the non-load bearing concrete panels. No gaps were found between load-bearing elements and therefore the loadpath as intended by the original design is unchanged. The Estate comprises of four geometrically identical 14-storey precast concrete Large Panel System (LPS) tower blocks. -

Vitality, Viability and Vulnerability Study

Report Report GVA 10 Stratton St London W1J 8JR Walworth Road Vitality Viability and Vulnerability Study London Borough of Southwark December 2014 gva.co.uk December 2014 gva.co.uk London Borough of Southwark Walworth Road Study CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5 2. The Walworth Road Context ................................................................................... 11 3. Spatial Structure ....................................................................................................... 25 4. The Business Environment ....................................................................................... 47 5. A Dynamic Context ................................................................................................. 53 6. Responding to Challenges & Opportunities ......................................................... 69 7. Learning from Others ............................................................................................... 73 8. Success Factors ....................................................................................................... 77 9. A Vision for the Walworth Road ............................................................................. 79 10. Towards a Strategy .................................................................................................. 90 Core Project Team GVA EAST December 2014 I gva.co.uk London Borough of Southwark Walworth Road VVV Study December