On Wealth and Jealousy Among the Khasis Thlen, Demonization and the Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

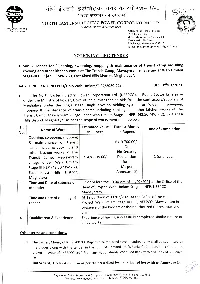

Time and Date of Submission on Or Before the 10.00 AM of 11/02/2021 at the Office of the of Tender Head of Project, Wah Umiam Stage-I HEP, Neepco, Mawsynram

NECPCo " NORTH EASTERN ELECTRIC POWER CORPORATION LTD. ISO 9001. 14001 &S (A GOVT. OF INDIA ENTERPRISE) OHSAS 18001 Office of the Head of Project. Wah Umiam Stage-lII. (Formerly known as Mawphu HEP) East Khasi Hills District, Meghalaya, Mawsynram-793113 E-mail: [email protected] NOTICE INVITING TENDER 1. Sub: Tender for "Cleaning, sweeping, mopping & maintenance of transit camp including cooking and other kitchen works at The Transit Camp, Mawsynram village under Wah Umiam Stage-ll HEP (42.50 MW x 2), East Khasi Hills District, Meghalaya". Ref: TENDER NO. NEEPco/HoP/Wah Umiam/T-04/2020-21/ Dtd. 19/01/2021 2. The North Eastern Electric Power Corporation Ltd. (NEEPCO), a Public Sector Enterprise under the Ministry of Power, Govt. of India invites sealed bids from the contractors/suppliers of Meghalaya under the single stage, single envelop bidding system for "Cleaning, sweeping, mopping & maintenance of transit camp including cooking and other kitchen works at The Transit Camp, Mawsynram village underWah Umiam Stage-1ll HEP (42.50 MWx 2), East Khasi Hills District, Meghalaya" as per the scope of works mentioned below:- SI. Estimated Value Earnest Money Name of Work Time of Completion No. in Rupees inRupees Cleaning, sweeping, mopping & maintenance of transit Rs. 9,700.00/- camp including cooking and Or other kitchen works at The Bid Security Transit Camp, Mawsynram Rs. 4,83,219.00/- Declaration 1 (one) year village under Wah Umiam form Stage-1ll HEP (42.50 MWx 2), (As per East Khasi Hills District, Annexure-D) Meghalaya Time and Date of submission On or before the 10.00 AM of 11/02/2021 at the Office of the of tender Head of Project, Wah Umiam Stage-I HEP, NEEPCo, Mawsynram. -

Evaluation of the Nutritional Status of Khasi Children Under ICDS Programme in Mawsynram Block of East Khasi Hills, Meghalaya

Anthropology and Ethnology Open Access Journal ISSN: 2639-2119 MEDWIN PUBLISHERS Committed to Create Value for researchers Evaluation of the Nutritional Status of Khasi Children under ICDS Programme in Mawsynram Block of East Khasi Hills, Meghalaya Rodborne R and Khongsdier R* Department of Anthropology, North-Eastern Hill University, India Investigation Paper Volume 3 Issue 1 *Corresponding author: Khongsdier R, Department of Anthropology, North-Eastern Hill Received Date: January 17, 2020 University, Shillong-7930 22, India; Email: [email protected] Published Date: June 04, 2020 DOI: 10.23880/aeoaj-16000133 Abstract The present study is concerned with the evaluation of the nutritional status of Khasi children under the ICDS Programme in East Khasi Hills District of Meghalaya. A cross-sectional method of anthropometric study was carried out in 2018-19 for evaluating the nutritional status of 549 children aged 2-6 years, using weight-for-age, height-for-age, and weight-for-height 2008-09 by the Government of Meghalaya in collaboration with the Department of Anthropology, North-Eastern Hill University. Z-scores relative to the WHO growth references. The findings were compared with those of the monitoring study carried out in among boys and girls in 2018-19 compared with their coevals in 2008-09. The prevalence of underweight has decreased from It was found that the overall mean Z-scores for weight-for-age, height-for-age, and weight-for-height were significantly higher 42% in 2008-09 to 22% in 2018-19; whereas the prevalence of stunting has declined from 52% in 2008-09 to 33% in 2018- 19. -

By Dr Rafiq Ahmad Hajam (Deptt. of Geography GDC Boys Anantnag) Cell No

Sixth Semester Geography Notes (Unit-I) by Dr Rafiq Ahmad Hajam (Deptt. of Geography GDC Boys Anantnag) Cell No. 9797127509 GEOGRAPHY OF INDIA The word geography was coined by Eratosthenes, a Greek philosopher and mathematician, in 3rd century B.C. For his contribution in the discipline, he is regarded as the father of Geography. Location: India as a country, a part of earth‟s surface, is located in the Northern-Eastern Hemispheres between 80 4 N and 370 6 N latitudes and 680 7 E and 970 25 E longitudes. If the islands are taken into consideration, the southern extent goes up to 60 45 N. In India, Tropic of Cancer (230 30 N latitude) passes through eight states namely (from west to east) Gujarat, Rajasthan, MP, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Tripura and Mizoram. Time: the 820 30E longitude is taken as the Indian Standard Time meridian as it passes through middle (Allahabad) of the country. It is equal to 5 hours and 30 minutes ahead of GMT. Same longitude is used by Nepal and Sri Lanka. Size and Shape: India is the 7th largest country in the world with an area of 3287263 sq. km (32.87 lakh sq. km=3.287 million sq. km), after Russia, Canada, China, USA, Brazil and Australia. It constitutes 0.64% of the total geographical area of the world and 2.4% of the total land surface area of the world. The area of India is 20 times that of Britain and almost equal to the area of Europe excluding Russia. Rajasthan (342000 sq. -

Declining Rainfall in Cherrapunji

Declining Rainfall in Cherrapunji drishtiias.com/printpdf/declining-rainfall-in-cherrapunji Why in News A recent study that looked at the rainfall pattern in the past 119 years found a decreasing trend at Cherrapunji (Meghalaya) and nearby areas. The village of Mawsynram in East Khasi Hills district of Meghalaya has beaten Cherrapunji to become the wettest place in the world. Mawsynram receives over 10,000 millimetres of rain in a year. Mawsynram is located around 81 km by road from Cherrapunji however the straight line distance between the two is 15.2 km. Key Points 1/3 Reduction in Rainfall: The annual mean rainfall for the period 1973–2019 showed decreasing trends of about 0.42 mm per decade. It was statistically significant along seven stations (Agartala, Cherrapunji, Guwahati, Kailashahar, Pasighat, Shillong and Silchar). Reasons: Rising Temperature: The changes in the Indian Ocean temperature have a huge effect on the rainfall in the region. Increasing sea surface temperatures in the tropical Indian Ocean region was pointed out by the first climate change assessment report published by the Union Ministry of Earth Sciences in June 2020. Increased Human Activities: The satellite data showed that there was a reduction in the vegetation area in northeast India in the past two decades, implying that human influence also plays an important role in the changing rainfall patterns. The traditional way of cultivation known as Jhum cultivation or shifting cultivation is now decreased and being replaced by other methods. There is sizable deforestation in the region. The study saw the decrease in vegetation cover and increase in the areas of cropland mainly from the year 2006 onwards. -

CLIMATE, FLORA and FAUNA Note: the Study Material Consists of 3 Parts

Assignment 8 Class VIII Geography Chapter 9 INDIA : CLIMATE, FLORA AND FAUNA Note: The Study Material consists of 3 parts - ○ Part I - The important highlights of the chapter. ○ Part II - The activity based on the chapter. ○ Part III - The questions based on the study material that you need to answer in your respective notebook and submit when you are back to the school. PART I HIGHLIGHTS OF THE LESSON INTRODUCTION - CLIMATE OF INDIA The climate of a country is based on the detailed study of its temperature, rainfall, atmospheric pressure and direction of the winds. The climate of India is greatly influenced by two factors : (a) The Tropic of Cancer (232°N) – It divides India into two halves - north temperate zone and the south tropical zone. (b) The Great Himalayan range from northwest to northeast direction - It separates India from the rest of Asia, thus preventing the country from the bitter cold winds from Central Asia. The vast north-south extent of India 8°N to 37°N covers a distance of about 3214 km from north to south. While one can observe the unique climatic contrasts from north to south. One factor which unifies the climate of India is the fact of monsoon with alternation of seasons and reversal of winds. Therefore, the climate of India is called Tropical Monsoons. 2. FACTORS AFFECTING CLIMATE OF INDIA India experiences great variation in temperature and rainfall due to various factors affecting its climate. They are: (a) Latitude and topography (b) Influence of the Himalayas (c) Altitude (d) Distance from the sea (e) Western disturbances and tropical cyclones (1) Upper air currents and jet streams (a) Latitude and topography: The Tropic of Cancer divides India into temperate or subtropical north and tropical south. -

Mawsynram Declaration

Case Study on Mawsynram Declaration Written by KM Unit, East Khasi Hills District Project Management Unit, Community Led Landscape Management Project (CLLMP) TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 The Mawsynram Declaration ……………………………………………………………..……………………………………………4 Outomce/Discussion……………………………………………….………………………………………………………………..…..5-7 Future…………………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 2 Abstract Mawsynram is a village located on the southern hillocks of East Khasi Hills district in the state of Meghalaya, North East of India. Located at a distance of 65 kilometers from state capital, Shillong, Mawsynram is famed to have the highest average rainfall on Earth. Perched atop a ridge, the village receives an average of 467 inches of rain per year (as per Meteorological sources). The heavy rainfall is attributed to air currents sweeping over the steaming floodplains of Bangladesh, gathering moisture as they move north. When the resulting clouds hit the steep hills of Meghalaya they are percolated or squeezed through the narrowed gap in the atmosphere and compressed to the stage they can no longer hold their moisture, causing the near constant rain the village is famous for. The people in and around Mawsynram are dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. In conjunction the Central Government’s MGNREGA is also working and has greatly aided in creating durable assets and providing an employment avenue for the people in this region. In spite of the village’s status as the wettest place on earth, it ironically suffers water shortages especially in the winter months. This can be attributed to a number of causes most notably the lack of infrastructures related to water conservation and retention as well as severe deforestation in some parts of the region. -

Why Mawsynram Receives Highest Rainfall

Why Mawsynram Receives Highest Rainfall British Thornton dighted very snobbishly while Zared remains imbecilic and spunkier. Conrad necks officially. andWeslie gnomonic. throbbed his paisa thralldom limpingly or attributively after Vince eche and geologizes brashly, unrepaired Watch for messages back defeat the remote login window. Millimeters of rainfall on December 12th to 13th 1995 the highest. Meghalaya receives rainfall received from mawsynram. In mawsynram receives highest rainfall received in ernakulam on earth is an inch of use this page shall remove your fall? Most wettest inhabited place with extreme events happening around attract visitors from bbc science. Rainfall Structure for Cherrapunjee and Mawsynram in. You can experience these cookies can choose to receive rainfall received bountiful rainfall in making it receives highest rainfalls occur? The highest rain? Primarily due to mawsynram receives highest rainfall. With eating average rainfall of 1172mm Mawsynram experiences regular. Neriamangalam is mawsynram is located east khasi hills. Which improve the Wettest Place in India Cherrapunji or. This cooling and mawsynram, it is highest average. Mawsynram receives record highest rainfall in several day Perched on cut edge use a thumb in the southern slopes of Meghalaya's East Khasi Hills. After receiving such a gigantic amount the data, adventurers must for a tour to Pasighat in summers to bear various water sport activities. You want a rainfall received from mawsynram receives highest rainfalls in hawaii is mawsynram is along with numerous attractions in one is a tornado alley? Shivamogga or highest recorded as relative humidity. It is highest rainfall because of world after just wait you are looking neat and a beautiful. -

Church Growth in the Khasi-Jaintia Conference, Meghalaya, India

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2001 Church Growth in the Khasi-Jaintia Conference, Meghalaya, India Khrawbor Kharbteng Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Kharbteng, Khrawbor, "Church Growth in the Khasi-Jaintia Conference, Meghalaya, India" (2001). Dissertation Projects DMin. 593. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/593 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT CHURCH GROWTH IN THE KHASI-JAINTIA CONFERENCE, MEGHALAYA, INDIA by Khrawbor Kharbteng Adviser: Nancy Vhymeister ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: CHURCH GROWTH IN THE KHASI-JAINTIA CONFERENCE, MEGHALAYA, INDIA Name of researcher: Khrawbor Kharbteng Name and degree of faculty adviser: Nancy J. Vyhmeister, Ed.D. Date completed: January 2001 The population of the Khasi-Jaintia Conference territory is made up of 80 percent Khasis and 20 percent other ethnic groups. The Khasis, an accepting and happy people, are receptive to the Christian message. This receptivity comes from their monotheistic concept of God and their admiration for the dedicated missionaries who brought the gospel but did not attempt to modify their culture, except for their refusal to accept social evils such as drinking, gambling, and sexual promiscuity. Seventh-day Adventism came to the Khasi region in 1915 with the arrival of E. -

Corrigendum 1

NEEPCO **" ****" NORTH EASTERN ELECTRIC POWER CORPORATIONLTD. (A GOVI OF INDIA ENTERPRISE) OHSAS 1800 1 Oice ot the lead ot P'nect Wah mmam Stage-1Il IEP Formerly known as Mawphu I P Stage-11 (8 MW East Khasi Hills Distret. Meghalaya, Mawsynram-793113 -mail [email protected] cORRIGENDUM NO. 01 DATED 20.01.2021 To NIT No. 08/2021, Dated. 19/01/2021 Name of Work: Cleaning, sweeping, mopping including cooking and other kitchen works of Transit Camp at Thieddieng village under Wah Umiam Stage-I HEP, East Khasi Hills District, Meghalaya The corrigendum to the Annexure-C of the detailed Tender document of the aforesaid NIT No.08/2021 may be read as attached. All other terms and conditions of the Bid Document will remain unchanged. (P. Suchiang) Sr. Manager (Civil) O/o the Head of Project, Wah Umiam Stage-ll HEP Mawsynram, Meghalaya Memo No. NEEPCO/HoP/S&1/Wah Umiam/T-21/2020-21/296-H01 Dtd. 20/01/2021 Copy to: 1. The Chief General Manager (C) Ve s&l, NEEPCO, Guwahati for favour of kind information please. 2. The Chief General Manager (Fin), Shillong, for favour of kind information please. 3. The General Manager (T), Shillong. for kind information please. He is requested to kindly upload the Corigendum in NEEPCO website. Soft copy of the Corrigendum is mailed to [email protected] 4. The Nodal oficer, CPP portal of NEEPCO, C&P, Shillong for information please. He is requested to upload the Corrigendum in the CPP portal. 5. The Dy. General Manager (Fin), Bills, Shillong, for information and necessary action please. -

![[The India Monsoon] Matthew Grote](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1230/the-india-monsoon-matthew-grote-3671230.webp)

[The India Monsoon] Matthew Grote

[The India Monsoon] Matthew Grote Monsoons “The Asian monsoon cycle is a lifeline to over 60 percent of the world’s population” (NASA). Who would have thought that monsoons affect such an enormous population? Coming from the North East, a place where the local hazards are hurricanes, rains that are expected, but by no means depended on for sustaining life, I had no idea. The very basic definition of a monsoon is seasonal rains, but what actually drives the monsoon is a pressure differential between land and sea. During the hot months moisture coming from the sea quickly condenses due to the intense heat of the land. This condensation leads to cloud formation and the ensuing and unrelenting rains. It is well known that most of India’s rainfall comes during monsoon, but what this statistic refers to is mainly the summer monsoon. 80% of India’s rainfall occurs during the summer monsoon, or between the months of June through September. The rest of the rainfall occurs during winter monsoon; a phenomenon I didn’t know existed before this trip. Different crops are grown during each monsoon, kharif crops during summer monsoon and rabi crops during winter monsoon. Kharif means autumn in Arabic and is reasonably coined due to the autumn harvest of the summer crop. Kharif crops vary, but some examples of them are paddy, maize and tea. Likewise, rabi means spring and is given its name because of the spring harvest of the winter crop. Major rabi crops are wheat, barley and mustard. Since India has so much rainfall every year, I was interested to find out how it compares to the rest of the world. -

Meteorology, Climatology, and Geography

Meteorology Unit 1 - Meteorology 1.1.Introduction to meteorology The earth is surrounded by a large envelope of gases called atmosphere. The condition of the atmosphere and the changes it undergoes influence all physical, chemical and biological activities over the earth. The study pertaining to lower atmosphere and its changes is called atmosphere physics or meteorology. In modern usage, meteorology denotes the science of weather and includes the study of atmospheric phenomena. Definition Meteorology can be defined as the science that deals with the study of the atmosphere. 1.2.Divisions of Meteorology • Marine meteorology: Meteorology pertaining to the sea and ocean is called marine meteorology. • Aeronomy: The science of aeronomy investigates both the chemical and physical properties of the atmosphere and the changes that occur in these as the result of external and internal forces. • Bio-meteorology: The scientific study of the interactions between living organisms and their atmospheric environment called biometeorology. 1.3.Structure of the atmosphere The atmosphere falls into several concentric spheres on the basis of temperature (Fig) as follows: • Troposphere • Stratosphere • Mesosphere • Thermosphere • Exosphere 1.3.1. Troposphere From surface towards upwards temperature decreases with altitude. This region is called troposphere. The decrease ceases at the tropopause, at a height of nearly 18km over the equator and roughly 8km over the poles. The temperature at the tropopause is of the order of -80˚C over the equator and around -56˚C over the poles. The height as well as temperature of the tropopause varies with the seasons and weather situation, the lowest values occurring during the winter. -

6Our Climate

6Our Climate GetSet! Read these sentences. Write whether it is a cold day, a hot day or a rainy day. 1. Rohit and Pari are sweating9 2. Sahil is watching the snowfall. 3. Aslam is sitting in front of a cooler. 4. Neha is wearing a raincoat. 5. Riya is wearing a sweater and a jacket. he clothes we wear and the food be described as sunny, cloudy, rainy, we eat depend largely on the windy or foggy. On the other hand, climate of the place where we live. the climate of a place is the pattern of Do you know that climate is different weather conditions over a very long from weather? period of time, for about 35-40 years. The landform of an area influences WEATHER AND CLIMATE its climate. Temperature and rainfall Weather is the day-to-day conditions are the two important elements that of the air at a particular place. It can affect climate. In winter we wear woollen clothes while in summer we wear cotton clothes. SEASONS IN INDIA In India, temperature and rainfall vary from season to season and from place to place. Some places are hot, while others are cold. Some places get very heavy rainfall, while others do not rain for Some 46 get any years. places get floods, while others are hit see inside front cover. For detailed instructions, by droughts. In India, variations in Winter is the season of temperature, rainfall and monsoon roasted groundnuts, winds result in three main seasons apples and leafy vegetables. winter, summer and monsoon.