Privileged Exclusion in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan: Ethnic Return Migration, Citizenship, and the Politics of (Not) Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

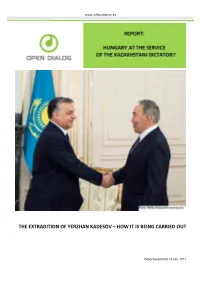

The Extradition of Yerzhan Kadesov – How It Is Being Carried Out

www.odfoundation.eu THE EXTRADITION OF YERZHAN KADESOV – HOW IT IS BEING CARRIED OUT Report published 14 July, 2017 www.odfoundation.eu The Open Dialog Foundation was established in Poland in 2009, on the initiative of Lyudmyla Kozlovska (who is currently the President of the Foundation). The statutory objectives of the Foundation include the protection of human rights, democracy and the rule of law in the post-Soviet area. The Foundation focuses its attention on countries in the region, in particular, such as: Kazakhstan, Moldova and Ukraine. The Foundation pursues its goals through the organisation of observation missions, including election observation and monitoring of the human rights situation in the post-Soviet area. Based on these activities, the Foundation creates its reports and distributes them among the institutions of the EU, and the OSCE , as well as other international organisations, foreign ministries and parliaments of EU countries, analytical centres and media. In addition to observational and analytical activities, the Foundation is actively engaged in cooperation with members of parliaments involved in foreign affairs, human rights and relationships with the post-Soviet countries, in order to support the process of democratisation and liberalisation of their internal policies. Other significant areas of the Foundation's activities include support of programmes for political prisoners and refugees. The Foundation has its permanent representative offices in Warsaw, Kyiv and Brussels. Copyright: Open Dialog Foundation, -

UK VISA REQUIREMENTS ALL Nationals of the Countries and Territories Listed Below in Red (Underlined) Need Visas to Enter Or Transit the UK

UK VISA REQUIREMENTS ALL nationals of the countries and territories listed below in red (underlined) need visas to enter or transit the UK. ALL nationals of the countries and territories listed below in black need visas to enter or transit the UK landside. ALL visa nationals may transit the UK without a visa (TWOV) in certain circumstances. Please see below for details. 1. Holders of diplomatic and special Afghanistan Comoros Indonesia (7) Morocco Sri Lanka passports do not require a visa for Albania Congo Iran Mozambique Sudan official visits, tourist visits or transit. Algeria Congo Dem. Iraq Myanmar (Burma) Surinam 2. Holders of diplomatic passports do not require a visa. Service passport Angola Republic Ivory Coast Nepal Syria (8) holders may transit without a visa. Armenia Cuba Jamaica Niger Taiwan (6) Holders of a public affairs passport Azerbaijan Cyprus northern Jordan Nigeria Tajikistan may not transit without a visa. Service Bahrain (1) part of (3) Kazakhstan North Macedonia Tanzania and public affairs passport holders do Bangladesh Djibouti Kenya Oman (5) Thailand not require a visa if travelling with a serving Chinese government minister Belarus Dominican Republic Korea (Dem. Pakistan Togo on an official visit to the UK. Benin Ecuador People’s Republic) Palestinian Tunisia 3. Passport not recognised by HM Bhutan Egypt Kosovo Territories Turkey (7) Government – visa should be issued Bolivia Equatorial Guinea Kuwait (5) Peru Turkmenistan on a uniform format form (UFF). Eritrea Uganda 4. Holders of diplomatic or official Bosnia and Kyrgyzstan Philippines passports may transit without a visa. Herzegovina Eswatini (Swaziland) Laos Qatar (5) Ukraine 5. -

1. Background Information

AD HOC QUERY ON 2019.57 SK AHQ on European travel document for return Requested by Simona MESZAROSOVA on 22 May 2019 Compilation produced on 25 September 2019 Responses from Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom plus Norway (22 in Total) Disclaimer: The following responses have been provided primarily for the purpose of information exchange among EMN NCPs in the framework of the EMN. The contributing EMN NCPs have provided, to the best of their knowledge, information that is up-to-date, objective and reliable. Note, however, that the information provided does not necessarily represent the official policy of an EMN NCPs' Member State. 1. Background information The Office of the Border and Foreign Police of the Police Force Presidium (hereinafter referred to as the “Office”) as the body responsible for the implementation of returns from the territory of the Slovak Republic is interested in continuously increasing the efficiency of returns by using all available means. One of the options is to actively use the European Travel Document for Return (EU Regulation regarding this particular document can be found here: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R1953...). Given that the document in question is used in situations where it is not 1 of 13. AD HOC QUERY ON 2019.57 SK AHQ on European travel document for return Disclaimer: The following responses have been provided primarily for the purpose of information exchange among EMN NCPs in the framework of the EMN. -

Countries Category “A” Exempt Foreign Visa

Organización de los Estados Americanos Organização dos Estados Americanos Organisation des États Américains- 1 - Organization of American States 17th and Constitution Ave., N.W. • Washington, D.C. 20006 TWENTY-FIRST INTERAMERICAN CONGRESS OF MINISTERS AND HIGH AUTHORITIES OF TOURISM September 5 - 6, 2013 San Pedro Sula, Honduras VISA REQUIREMENTS TO ENTER HONDURAS The Passport must be valid to enter to Honduras. COUNTRIES CATEGORY “A” EXEMPT FOREIGN VISA CATEGORY CLASIFICATION "A" DIPLOMATIC, No COUNTRY REGULAR PASSPORT OFFICIAL, AND OBSERVATIONS . SERVICE PASSPORT 1 Germany (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 2 Andorra (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 3 Antigua y Barbuda (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 4 Argentina (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 5 Australia (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 6 Austria (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 7 Bahamas (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 8 Bahrain (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 9 Barbados (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 10 Belgium (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 11 Belize (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 12 Brazil (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 13 Brunei‐Darussalam (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 14 Bulgaria (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 15 Canada (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 16 Chile (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 17 Cyprus (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT Korea, Republic of (South 18 (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT Korea) 19 Colombia (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 20 Costa Rica (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 21 Croatia (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 22 Denmark (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 23 El Salvador (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 24 Slovakia (Slovak Republic) (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 25 Ecuador (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 26 Slovenia (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT 27 Spain (A) VISA EXEMPT (A) VISA EXEMPT CATEGORY CLASIFICATION "A" DIPLOMATIC, No COUNTRY REGULAR PASSPORT OFFICIAL, AND OBSERVATIONS . -

Examining the Pressure on Human Rights in Kyrgyzstan

Retreating Rights: Examining the pressures on human rights in Kyrgyzstan Executive Summary Kyrgyzstan has just experienced another period of rapid and chaotic change, the third time the country has overthrown an incumbent President in the last 15 years. This publication shows how the roots of the problem run deep. It explores how a culture of corruption and impunity have been at the heart of Kyrgyzstan’s institutional failings, problems that have sometimes been overlooked or downplayed because of the comparison to challenges elsewhere in Central Asia, but that were ruthlessly exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The publication tries to explain the recent emergence of the new President Sadyr Japarov in the unrest of October 2020 and what it might mean for the future of Kyrgyzstan. An instinctive anti-elite populist with a powerful personal narrative and a past reputation for economic nationalism Japarov is undertaking a rapid consolidation of power, including through controversial constitutional reform. Liberal minded civil society has been under increasing pressure throughout the last decade. They have faced successive governments increasingly seeking to regulate and pressure them and a rising tide of nationalism that has seen hatred against civil society activists expressed on the streets and online, particularly due to the weaponisation of work on women’s and LGBTQ rights. The publication proposes a root and branch rethink of donor initiatives in Kyrgyzstan to take stock of the situation and come again with new ways to help, including the need for greater flexibility to respond to local issues, opportunities for new ideas and organisations to be supported, and a renewed focus on governance, transparency and accountability. -

Visa Advice for Maltese Nationals Notification from the Ministry For

VISA ADVICE FOR MALTESE NATIONALS NOTIFICATION FROM THE MINISTRY FOR FOREIGN AND EUROPEAN AFFAIRS LAST UPDATE: 01 October 2021 Please note that in view of the Covid pandemic- not all countries are open for travel. There are also Maltese Legal Notices concerning Travel Bans whereby Maltese nationals and persons residing in Malta may require special authorisation from Maltese Health Authorities in order to travel (https://deputyprimeminister.gov.mt/en/health- promotion/covid-19/Pages/travel.aspx ) In specific cases, the rules concerning visas have changed or been suspended. Therefore, please do contact our Visa Advisory Unit on 22042331 or 22042313 or write an e-mail to [email protected] to double check directly whether the positions outlined below still apply or otherwise. The list below reflects the position under ‘normal’ (non-covid) circumstances. Disclaimer: The Ministry for Foreign and European Affairs is not responsible for the issuing of visas to Maltese nationals by foreign states. Visa requirements for Maltese nationals going abroad are invariably subject to changes by host countries. The Ministry for Foreign and European Affairs through its Visa Advisory Unit endeavours to provide information available to it at the time of submission of the query. The information related to visa requirements contained in this document is only indicative, and is issued to assist Maltese passport holders. The Ministry shall not be held responsible for any variance in the information provided. The applicant may wish to double-check requirements independently of this service. It is the responsibility of the applicant to ensure that enquiries are submitted well in advance of the planned date of departure. -

Visa Requirements for Bahamians Travelling Overseas

VISA REQUIREMENTS FOR BAHAMIANS TRAVELLING OVERSEAS COUNTRY NAME DOCUMENT REQUIREMENT VISA REQUIREMENT AFGHANISTAN, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES ALBANIA, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES ALGERIA, DEM. & POP REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES ANDORRA, PRINCIPALITY OF PASSPORT NO ANGOLA, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA PASSPORT NO ARGENTINA (ARGENTINE REPUBLIC) PASSPORT YES ARMENIA, REPUBLIC PASSPORT YES ARUBA (DUTCH AUTONOMOUS STATE) PASSPORT NO AUSTRALIA, COMMONWEALTH OF PASSPORT YES AUSTRIA, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT NO (90 days) AZERBAIJAN, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES AZORES (PORTUGUESE) PASSPORT YES BAHRAIN, STATE OF PASSPORT YES BANGLADESH, PEOPLE'S REP. OF PASSPORT YES BARBADOS PASSPORT NO BELARUS, REPUBLIC PASSPORT YES BELGIUM, KINGDOM OF PASSPORT NO (90 days) BELIZE PASSPORT NO BENIN, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES BERMUDA (UK DEPENDENCY ) PASSPORT NO BHUTAN, KINGDOM PASSPORT CALL FOR INFO BOLIVIA, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA, REP. OF PASSPORT YES BOTSWANA, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT NO BRAZIL, FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT NO^^^^^ BRUNEI DARUSSALAM, STATE OF PASSPORT YES BULGARIA, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT NO (90 days) BURKINA FASO PASSPORT YES BURUNDI, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES VISA REQUIREMENTS FOR BAHAMIANS TRAVELLING OVERSEAS COUNTRY NAME DOCUMENT REQUIREMENT VISA REQUIREMENT CAMBODIA PASSPORT YES CAMEROON. REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES CANADA PASSPORT NO CAPE VERDE, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES CAYMAN ISLANDS (UK DEPENDENCY) PASSPORT NO CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC PASSPORT YES CHAD, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT YES CHILE, REPUBLIC OF PASSPORT NO CHINA, PEOPLE’S -

Visa Requirements for South African Diplomatic and Official Passport

DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS And COOPERATION (DIRCO) SOUTH AFRICAN DIPLOMATIC AND OFFICIAL PASSPORT HOLDERS VISA REQUIREMENTS COUNTRY VISA FORM PHOTO NOTE REMARKS VERBALE Angola - - - - No visa required up to 90 days No visa required for posting as well Australia X X 1 NV Applicant must complete Form 1415, Business visitor’s stream online application form available on http://www.immi.gov.au/Services/Pages/visitor- e600-visa-online-applications.aspx Officials on diplomatic posting no application form to be completed, only a Note Verbale stating all the appropriate information. See Annexure “A” below. Transit Visa required for stopovers longer than eight (8) hours when travelling via Australia. Argentina - - - - No visa required up to 90 days. No visa required for officials going on posting Austria - - - - No visa required for up to 90 ninety days for holders of official and diplomatic passports. Officials on posting: Diplomatic and official/service passport holders of both countries do not require visas when reporting for assignments to their missions in South Africa. The Sending state must inform the Receiving State by Note Verbale of the assignments before the assignments actually realize. Algeria - - - - No visa required for 30 days X X X X A visa is required for posting 2 new colored photos Copy of passport (first page) Flight reservation Processing 15 working days Albania - - - - No visa required up to 120 days Afghanistan X - - - No Information Andorra X - - - No Information Antigua and - - - - Barbuda No visa required Armenia X - - Visa is required but no Representative in SA, Updated 10 July 2019 applications lodged via Armenian Embassy in Cairo, Egypt. -

System Identified Errors

CBP Bus APIS Document Guidance U.S. Customs and Border Protection Office of Field Operations Version 1.0 October 2011 SUITABLE FOR PUBLIC DISSEMINATION Executive Summary To better facilitate commercial bus travel, voluntary Advance Passenger Information System (APIS) manifests can be submitted to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) for buses arriving in or departing from certain United States ports of entry. These electronically submitted manifests are to include all travelers (passengers and crew) aboard each bus. This guide provides information pertaining to some of the most common travel documents bus carriers may encounter when collecting manifest information for submission to CBP. It does not address the validity of documents for land border crossings into and out of the United States. Additional information on acceptable documents is available on the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative (WHTI) website at www.getyouhome.gov. Carriers can also refer to the Carrier Information Guide at http://www.cbp.gov/xp/cgov/travel/inspections_carriers_facilities/carrier_info_guide/. This guide is designed to serve as a reference aid and is intended as general guidance to assist persons responsible for submitting bus APIS data with the submission of document information. It is not intended to cover every possible document that may be submitted. This document does not create or confer any right or benefit on any person or party, private or public. SUITABLE FOR PUBLIC DISSEMINATION 1 October, 2011 – CBP Bus APIS Document Guidance, Version 1.0 Table of Contents I. General Document Information…………………………………………………… 3 II. Specific Document Submission Data………………………………..…..………… 3 III. Document Images and Examples…………………………………………………. 4 IV. Summary…………………………………………………………………………… 10 Appendix I - Document Codes and Descriptions……………………………………… 11 Appendix II - Country Codes………………………………………………………….. -

Weaponized Passports: the Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness

Weaponized Passports: the Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness • The Chinese government has long weaponized access to passports through corruption, confiscations, and discriminatory procedures. Control is now exerted through effectively denying Uyghurs the right to a passport. • Chinese embassy officials tell Uyghurs that the only way to renew a passport is to return to China. Those Uyghurs who have returned to China have disappeared. Lack of documentation impacts the livelihoods, marriages, living situations, studies, and freedom of movement of Uyghurs abroad. • UHRP recommends that states recognize the deprivation of passports as a violation of Uyghur rights, and understand the danger that returning to China presents to Uyghurs. States should ensure that Uyghurs have access to Convention Travel Documents, and are granted asylee status in a timely manner. • States which host Uyghur populations should ensure that they are granted legal status and documentation, and access to public services such as schools. April 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 3 DENYING PASSPORTS TO UYGHURS: A GLOBAL PROBLEM ..................................... 6 (1) Primary Research with Uyghurs in Turkey ......................................................................... 6 (a) Passport Agents: “Abdugheni’s” Story ..................................................................................... 6 (b) Changing Policies on Issuing Passports -

Privileged Exclusion in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan: Ethnic

Privileged Exclusion in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan: Ethnic Return Migration, Citizenship, and the Politics of (Not) Belonging Cynthia Werner, Celia Emmelhainz, and Holly Barcus This is a pre-publication version of a peer-reviewed paper published in 2017 in Europe-Asia Studies, 69(10), p. 1557-1583. If possible, please download and cite final wording and page numbers at https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2017.1401042. Abstract This essay explores issues of citizenship and belonging associated with post-Soviet Kazakhstan’s repatriation program. Beginning in 1991, Kazakhstan financed the resettlement of over 944,000 diasporic Kazakhs from nearly a dozen countries, including Mongolia, and encouraged repatriates to become naturalized citizens. Using the concept of privileged exclusion, we argue that repatriated Kazakhs from Mongolia simultaneously belong due to their knowledge of Kazakh language and traditions, yet do not belong due to their lack of linguistic fluency in Russian, the absence of a shared Soviet experience, and limited comfort with the ‘cosmopolitan’ lifestyle that characterizes the new elite in this post-Soviet context. Tags: Citizenship, belonging, nation-building, migration, Kazakhstan, Kazakhs, post-soviet Introduction While sipping tea in her daughter’s kitchen in Mongolia, Anara, a woman in her late sixties, told us about her experience migrating from Mongolia to Kazakhstan.1 Anara and her husband Serik are Kazakhs who were born and raised in western Mongolia. Until the early 1990s, they enjoyed a comfortable yet modest life in a predominantly Kazakh region. Yet like other professionals whose education and occupation represented Mongolia’s ‘middle class’, Anara and Serik lost their jobs as a pharmacist and truck driver respectively when the post- socialist Mongolian government introduced neoliberal reforms in 1991. -

Costa Rica Guidelines for Visas

COSTA RICA GUIDELINES FOR VISAS The following document provides the list of requirements to obtain a visa in Costa Rica, which are divided into 4 groups: Group 1.Do not require visa. Group 2.Visa required for stays of more than thirty days. Group 3.The citizens from those countries require consular visa. Group 4 restricted Visa. The citizens from those countries require consular visa and approval of the Directorate of Immigration. For those people participating in the International Forum on Payments for Environmental Services of Tropical Forests that come from countries included in Group 3 and 4, please fill out the Visa Requirement Form, in order to receive a visa uppon arrival. Also, participants from those countries please take note of the exceptions listed in this document. GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR VISAS NON-RESIDENTS LEGAL BASIS (MIGRATION AND IMMIGRATION LAW, LAW No. 8764) Article 47. - The General Direction of Migration shall establish general guidelines for entry and stay visas to non-residents for foreigners from certain countries or geographical areas, based on existing agreements and international treaties and security reasons, convenience or opportunity for the Costa Rican government. Article 51. - Foreign persons seeking access under the immigration status of non-residents, except as determined by the general guidelines for entry and stay visas for non-residents require a visa for entry. The length of stay will be authorized by the official of the Directorate General admission of the alien into the country based on the guidelines established by the Directorate General. Prior to granting the visa, migration agents must obtain outside of the Directorate General, the respective entry clearance, where applicable, in accordance with the general guidelines for entry and stay visas for non-residents FIRST GROUP The entry without a visa of nationals of the following with a maximum stay of up to 90 calendar days is permitted.