A Jazz Musician's Journey Into the Heart of Indian Classical Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MODAL ANALYSIS and TRANSCRIPTION of STROKES of the MRIDANGAM USING NON-NEGATIVE MATRIX FACTORIZATION Akshay Anantapadmanabhan1, Ashwin Bellur2 and Hema a Murthy1 ∗

MODAL ANALYSIS AND TRANSCRIPTION OF STROKES OF THE MRIDANGAM USING NON-NEGATIVE MATRIX FACTORIZATION Akshay Anantapadmanabhan1, Ashwin Bellur2 and Hema A Murthy1 ∗ 1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, 2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, India - 600 036 ABSTRACT The mridangam is quite different from the tabla in that, the mridangam is a single body instrument with two membranes In this paper we use a Non-negative Matrix Factorization (one producing treble sounds while the other producing bass (NMF) based approach to analyze the strokes of the mri- sounds) as opposed to the tabla, which consists of two inde- dangam, a South Indian hand drum, in terms of the normal pendent bodies. C.V. Raman, in his work on Indian musical modes of the instrument. Using NMF, a dictionary of spectral drums [1], discusses some of the unique traits of the mridan- basis vectors are first created for each of the modes of the gam as a harmonic percussive instrument. He describes some mridangam. The composition of the strokes are then studied of the structural similarities between the mridangam and tabla by projecting them along the direction of the modes using but at the same time highlights some of the major differences NMF. We then extend this knowledge of each stroke in terms in their acoustic properties. He also illustrates the modes of of its basic modes to transcribe audio recordings. Hidden the mridangam using sand figures to reveal the basic physical Markov Models are adopted to learn the modal activations for and acoustic characteristics of the instrument. -

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Maestro Plays Traditional Tabla

PERFORMAN CE Maestro plays traditional tabla By Arthur Dudney Hu s!ain wi ll be a visiting PlI.IH(:ETOHJAH STA" W RITER faculty member in the music departmen t next se mester, The instrument W: simple tt!aching a -e:ouue titled "in - a large drum and a small troduction to the Music of in drum. played with the fingers dia," which he designed with and palm. But Zaki r Hu ssain mathematics professor and plays the traditional Indian tabla enthusiast Manjul Bh ar instrument, the tabla, with gava. such subtlety that there see ms The appointment is funded to be more to it. by theCounci! of the Humani Nearly 300 community ties. members attended his recital Hussain brgan to study tab Thursday aft ernoon tohear th e la seriously .a t age sev('n with man internationally re nowned hi s father, and the two began for hi s fusion of classica l in touring together when Zakir dian and Western music. Su TABLA pagt4 )RINCETONIAN Friday APRIL 8, 200S Hussain discusses tabla history TABLA of his many appearances at the to work with hi s colleagues in Un iversity since 1974 - began the music department, espe Co nfinutd from pa,9t I with five minutes of virtuos cially those involved in elec ity demonstrating the instru tronic music. was 12. Hi s fa ther, Ali a Rakha, ment's range. He then intro "Princeton is a respected was wide ly considered one of duced himse lf: "My n.ame is education center and I'm look the greates t tabla players of all Zakir Hu ssain and 1 play this ing at this not as something to time. -

Categorization of Stringed Instruments with Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis

CATEGORIZATION OF STRINGED INSTRUMENTS WITH MULTIFRACTAL DETRENDED FLUCTUATION ANALYSIS Archi Banerjee*, Shankha Sanyal, Tarit Guhathakurata, Ranjan Sengupta and Dipak Ghosh Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 *[email protected] * Corresponding Author ABSTRACT Categorization is crucial for content description in archiving of music signals. On many occasions, human brain fails to classify the instruments properly just by listening to their sounds which is evident from the human response data collected during our experiment. Some previous attempts to categorize several musical instruments using various linear analysis methods required a number of parameters to be determined. In this work, we attempted to categorize a number of string instruments according to their mode of playing using latest-state-of-the-art robust non-linear methods. For this, 30 second sound signals of 26 different string instruments from all over the world were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA) technique. The spectral width obtained from the MFDFA method gives an estimate of the complexity of the signal. From the variation of spectral width, we observed distinct clustering among the string instruments according to their mode of playing. Also there is an indication that similarity in the structural configuration of the instruments is playing a major role in the clustering of their spectral width. The observations and implications are discussed in detail. Keywords: String Instruments, Categorization, Fractal Analysis, MFDFA, Spectral Width INTRODUCTION Classification is one of the processes involved in audio content description. Audio signals can be classified according to miscellaneous criteria viz. speech, music, sound effects (or noises). -

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For Component 3: Appraising)

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances The composer Anoushka Shankar was born in 1981, in London, and is the daughter of the famous sitar player Ravi Shankar. She was brought up in London, Delhi and California, where she attended high school. She studied sitar with her father from the age of 7, began playing tampura in his concerts at 10, and gave her first solo sitar performances at 13. She signed her first recording contract at 16 and her first three album releases were of Indian Classical performances. Her first cross-over/fusion album – Rise – was released in 2005 and was nominated for a Grammy, in the Contemporary World Music category. Her albums since Breathing Under Water have continued to explore the connections between Indian music and other styles. She has collaborated with some major artists – Sting, Nithin Sawhney, Joshua Bell and George Harrison, as well as with her father, Ravi Shankar, and her half-sister, Norah Jones. She has also performed around the world as a Classical sitar player – playing her father’s sitar concertos with major orchestras. The piece Breathing Under Water was Anoushka Shankar’s fifth album, and her second of original fusion music. Her main collaborator was Utkarsha (Karsh) Kale, an Indian musician and composer and co-founder of Tabla Beat Science – an Indian band exploring ambient, drum & bass and electronica in a Hindustani music setting. Kale contributes dance music textures and technical expertise, as well as playing tabla, drums and guitar on the album. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

A Real-Time Synthesis Oriented Tanpura Model

Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx-16), Brno, Czech Republic, September 5–9, 2016 A REAL-TIME SYNTHESIS ORIENTED TANPURA MODEL Maarten van Walstijn, Jamie Bridges, and Sandor Mehes Sonic Arts Research Centre School of Electronics, Electrical Engineering, and Computer Science Queen’s University Belfast, UK {m.vanwalstijn,jbridges05,smehes01}@qub.ac.uk cotton ABSTRACT thread finger Physics-based synthesis of tanpura drones requires accurate sim- tuning bridge nut ulation of stiff, lossy string vibrations while incorporating sus- bead tained contact with the bridge and a cotton thread. Several chal- lenges arise from this when seeking efficient and stable algorithms 0 xc xb → x xe L for real-time sound synthesis. The approach proposed here to address these combines modal expansion of the string dynamics Figure 1: Schematic depiction of the tanpura string geometry (with with strategic simplifications regarding the string-bridge and string- altered proportions for clarity). The string termination points of the thread contact, resulting in an efficient and provably stable time- model are indicated with the vertical dashed lines. stepping scheme with exact modal parameters. Attention is given also to the physical characterisation of the system, including string damping behaviour, body radiation characteristics, and determi- the reliance on iterative solvers and from the high sample rates nation of appropriate contact parameters. Simulation results are needed to alleviate numerical dispersion. presented exemplifying the key features of the model. This paper aims to formulate a leaner discrete-time tanpura string model requiring significantly reduced computational effort, but retaining much of the key sonic features of the instrument. -

Analyzing the Melodic Structure of a Raga-Based Song

Georgian Electronic Scientific Journal: Musicology and Cultural Science 2009 | No.2(4) A Statistical Analysis Of A Raga-Based Song Soubhik Chakraborty1*, Ripunjai Kumar Shukla2, Kolla Krishnapriya3, Loveleen4, Shivee Chauhan5, Mona Kumari6, Sandeep Singh Solanki7 1, 2Department of Applied Mathematics, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India 3-7Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India * email: [email protected] Abstract The origins of Indian classical music lie in the cultural and spiritual values of India and go back to the Vedic Age. The art of music was, and still is, regarded as both holy and heavenly giving not only aesthetic pleasure but also inducing a joyful religious discipline. Emotion and devotion are the essential characteristics of Indian music from the aesthetic side. From the technical perspective, we talk about melody and rhythm. A raga, the nucleus of Indian classical music, may be defined as a melodic structure with fixed notes and a set of rules characterizing a certain mood conveyed by performance.. The strength of raga-based songs, although they generally do not quite maintain the raga correctly, in promoting Indian classical music among laymen cannot be thrown away. The present paper analyzes an old and popular playback song based on the raga Bhairavi using a statistical approach, thereby extending our previous work from pure classical music to a semi-classical paradigm. The analysis consists of forming melody groups of notes and measuring the significance of these groups and segments, analysis of lengths of melody groups, comparing melody groups over similarity etc. Finally, the paper raises the question “What % of a raga is contained in a song?” as an open research problem demanding an in-depth statistical investigation. -

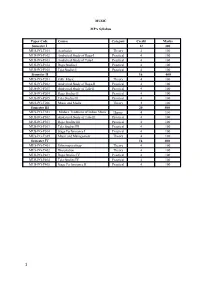

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

The West Bengal College Service Commission State

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION STATE ELIGIBILITY TEST Subject: MUSIC Code No.: 28 SYLLABUS Hindustani (Vocal, Instrumental & Musicology), Karnataka, Percussion and Rabindra Sangeet Note:- Unit-I, II, III & IV are common to all in music Unit-V to X are subject specific in music Unit-I Technical Terms: Sangeet, Nada: ahata & anahata , Shruti & its five jaties, Seven Vedic Swaras, Seven Swaras used in Gandharva, Suddha & Vikrit Swara, Vadi- Samvadi, Anuvadi-Vivadi, Saptak, Aroha, Avaroha, Pakad / vishesa sanchara, Purvanga, Uttaranga, Audava, Shadava, Sampoorna, Varna, Alankara, Alapa, Tana, Gamaka, Alpatva-Bahutva, Graha, Ansha, Nyasa, Apanyas, Avirbhav,Tirobhava, Geeta; Gandharva, Gana, Marga Sangeeta, Deshi Sangeeta, Kutapa, Vrinda, Vaggeyakara Mela, Thata, Raga, Upanga ,Bhashanga ,Meend, Khatka, Murki, Soot, Gat, Jod, Jhala, Ghaseet, Baj, Harmony and Melody, Tala, laya and different layakari, common talas in Hindustani music, Sapta Talas and 35 Talas, Taladasa pranas, Yati, Theka, Matra, Vibhag, Tali, Khali, Quida, Peshkar, Uthaan, Gat, Paran, Rela, Tihai, Chakradar, Laggi, Ladi, Marga-Deshi Tala, Avartana, Sama, Vishama, Atita, Anagata, Dasvidha Gamakas, Panchdasa Gamakas ,Katapayadi scheme, Names of 12 Chakras, Twelve Swarasthanas, Niraval, Sangati, Mudra, Shadangas , Alapana, Tanam, Kaku, Akarmatrik notations. Unit-II Folk Music Origin, evolution and classification of Indian folk song / music. Characteristics of folk music. Detailed study of folk music, folk instruments and performers of various regions in India. Ragas and Talas used in folk music Folk fairs & festivals in India. Unit-III Rasa and Aesthetics: Rasa, Principles of Rasa according to Bharata and others. Rasa nishpatti and its application to Indian Classical Music. Bhava and Rasa Rasa in relation to swara, laya, tala, chhanda and lyrics. -

4 Broadcast Sector

MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING Annual Report 2006-2007 CONTENTS Highlights 1. Overview 1 2. Administration 3 3. Information Sector 12 4. Broadcast Sector 53 5. Films Sector 110 6. International Co-operation 169 7. Plan and Non-Plan Programmes 171 8. New Initiatives 184 Appendices I. Organisation Chart of the Ministry 190 II. Media-wise Budget for 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 192 Published by the Director, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India Typeset at : Quick Prints, C-111/1, Naraina, Phase - I, New Delhi. Printed at : Overview 3 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR The 37th Edition of International Film Festival of India-2006 was organized in Goa from 23rd November to 3rd December 2006 in collaboration with State Government of Goa. Shri Shashi Kapoor was the Chief Guest for the inaugural function. Indian Film Festivals were organized under CEPs/Special Festivals abroad at Israel, Beijing, Shanghai, South Africa, Brussels and Germany. Indian films also participated in different International Film Festivals in 18 countries during the year till December, 2006. The film RAAM bagged two awards - one for the best actor and the other for the best music in the 1st Cyprus International Film Festival. The film ‘MEENAXI – A Tale of Three Cities’ also bagged two prizes—one for best cinematography and the other for best production design. Films Division participated in 6 International Film Festivals with 60 films, 4 National Film Festivals with 28 films and 21 State level film festivals with 270 films, during the period 1-04-06 to 30-11-06. Films Division Released 9791 prints of 39 films, in the theatrical circuits, from 1-4-06 to 30-11-06.