L'abecedaire De Gilles Deleuze, Avec Claire Parnet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern

1st First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern. arr. Ozzie Westley (1944) BPC The Barberpole Cat Program and Song Book. (1987) BB1 Barber Shop Ballads: a Book of Close Harmony. ed. Sigmund Spaeth (1925) BB2 Barber Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1940) CBB Barber Shop Ballads. (Cole's Universal Library; CUL no. 2) arr. Ozzie Westley (1943?) BC Barber Shop Classics ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1946) BH Barber Shop Harmony: a Collection of New and Old Favorites For Male Quartets. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1942) BM1 Barber Shop Memories, No. 1, arr. Hugo Frey (1949) BM2 Barber Shop Memories, No. 2, arr. Hugo Frey (1951) BM3 Barber Shop Memories, No. 3, arr, Hugo Frey (1975) BP1 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 1. (1946) BP2 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 2. (1952) BP Barbershop Potpourri. (1985) BSQU Barber Shop Quartet Unforgettables, John L. Haag (1972) BSF Barber Shop Song Fest Folio. arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1948) BSS Barber Shop Songs and "Swipes." arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1946) BSS2 Barber Shop Souvenirs, for Male Quartets. New York: M. Witmark (1952) BOB The Best of Barbershop. (1986) BBB Bourne Barbershop Blockbusters (1970) BB Bourne Best Barbershop (1970) CH Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle (1936) CHR Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle. Revised (1941) CH1 Close Harmony: Male Quartets, Ballads and Funnies with Barber Shop Chords. arr. George Shackley (1925) CHB "Close Harmony" Ballads, for Male Quartets. (1952) CHS Close Harmony Songs (Sacred-Secular-Spirituals - arr. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

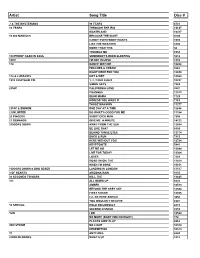

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring. -

English Songs

English Songs 18000 04 55-Vũ Luân-Thoại My 18001 1 2 3-Gloria Estefan 18002 1 Sweet Day-Mariah Carey Boyz Ii M 18003 10,000 Promises-Backstreet Boys 18004 1999-Prince 18005 1everytime I Close My Eyes-Backstr 18006 2 Become 1-Spice Girls 18007 2 Become 1-Unknown 18008 2 Unlimited-No Limit 18009 25 Minutes-Michael Learns To Rock 18010 25 Minutes-Unknown 18011 4 gio 55-Wynners 18012 4 Seasons Of Lonelyness-Boyz Ii Me 18013 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover-Paul S 18014 500 Miles Away From Home-Peter Pau 18015 500 Miles-Man 18016 500 Miles-Peter Paul-Mary 18017 500 Miles-Unknown 18018 59th Street Bridge Song-Classic 18019 6 8 12-Brian McKnight 18020 7 Seconds-Unknown 18021 7-Prince 18022 9999999 Tears-Unknown 18023 A Better Love Next Time-Cruise-Pa 18024 A Certain Smile-Unknown 18025 A Christmas Carol-Jose Mari Chan 18026 A Christmas Greeting-Jeremiah 18027 A Day In The Life-Beatles-The 18028 A dear John Letter Lounge-Cardwell 18029 A dear John Letter-Jean Sheard Fer 18030 A dear John Letter-Skeeter Davis 18031 A dear Johns Letter-Foxtrot 18032 A Different Beat-Boyzone 18033 A Different Beat-Unknown 18034 A Different Corner-Barbra Streisan 18035 A Different Corner-George Michael 18036 A Foggy Day-Unknown 18037 A Girll Like You-Unknown 18038 A Groovy Kind Of Love-Phil Collins 18039 A Guy Is A Guy-Unknown 18040 A Hard Day S Night-The Beatle 18041 A Hard Days Night-The Beatles 18042 A Horse With No Name-America 18043 À La Même Heure Dans deux Ans-Fema 18044 A Lesson Of Love-Unknown 18045 A Little Bit Of Love Goes A Long W- 18046 A Little Bit-Jessica -

David Taylor - Poems

Poetry Series David Taylor - poems - Publication Date: 2007 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive David Taylor(3rd January 1956) Born, Baby, Child, Adolescent, Student, Employee, Husband, Self Employed, Father, Father, Father, Divorcee, Husband, Father...and throughout all that I'm me! www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 *alone* what should be an invigorating freshness a chill inside (shaking heart beats) traffic on the road silent rising clanking passing (silent again) phone rings silence, recorded voice speaks a real person with taped speech (a recorded message would be better?) selling cheap energy i think i will buy some flowers (petals coloured fragrance) arrange them in a wreath celebrate my death reports of (my) death greatly exaggerated until the silence speaks with the voice of great souls (departed) come in they say (here is the place) to be; alone in eternity. David Taylor www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 *dance Ohh bliss what do you say, do you have a voice today? Where may I find your joy, which I remember as a boy? Ahh bliss where are you now, hidden under frown of brow? Where may I find your sound, which surely must be all around? Hmm bliss what is it that I miss, as I go on with that and this? Where may I find your smile, in each and every hour and mile? Yes I can feel it now, the harmony of the sky and clouds, the moon's revolving round, earth's harvest after plough. It is a dance eternal found the sweetest movement in all sound; and never will be missed, as by that bliss this life is kissed. -

Linda Davis to Matt King

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre Linda Davis From The Inside Out Country Linda Davis I Took The Torch Out Of His Old Flame Country Linda Davis I Wanna Remember This Country Linda Davis I'm Yours Country Linda Ronstadt Blue Bayou Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Different Drum Pop Linda Ronstadt Heartbeats Accelerating Country Linda Ronstadt How Do I Make You Pop Linda Ronstadt It's So Easy Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt I've Got A Crush On You Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Love Is A Rose Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Silver Threads & Golden Needles Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt That'll Be The Day Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt What's New Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt When Will I Be Loved Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt You're No Good Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville All My Life Pop / Rock Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Don't Know Much Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville When Something Is Wrong With My Baby Pop Linda Ronstadt & James Ingram Somewhere Out There Pop / Rock Lindsay Lohan Over Pop Lindsay Lohan Rumors Pop / Rock Lindsey Haun Broken Country Lionel Cartwright Like Father Like Son Country Lionel Cartwright Miles & Years Country Lionel Richie All Night Long (All Night) Pop Lionel Richie Angel Pop Lionel Richie Dancing On The Ceiling Country & Pop Lionel Richie Deep River Woman Country & Pop Lionel Richie Do It To Me Pop / Rock Lionel Richie Hello Country & Pop Lionel Richie I Call It Love Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

Community Hoot at Common Fence Music,He’

Quarantime: Why not learn to play an instrument? Okee dokee folks… Last week I wrote about the way social distancing and the show cancellations that came in its wake have affected artists. If you didn’t have a chance to read it, please do. (https://motifri.com/music-in-the-time-of-corona-musicians-talk-about-the-impact-of-losing-gigs-during-so cial-distancing/ ) “We are all pretty much in the same boat and that boat is the Titanic and it just hit the iceberg. Some folks are taking off alone in the lifeboats while others are giving up their seats.” I will add, “The captain is a moron and his ineptness is adding to the panic.” My good friend and bandmate Dan Lilley has the perfect song for this. His “No Captain at the Wheel” is a great tune about lack of leadership. If any of the past month’s shows had gone on, you could have had the pleasure of seeing him perform it live. Hopefully a recording of it will show up online. Turn on the music, turn off Trump. He is a directionless, narcissistic sociopath and is trying to feed his ego by holding daily press briefings only because he can’t hold his own rallies. His denial is what got us into this mess. A proper pandemic response would have lessened what is happening now. My stomach turns from anything Trump. He is the real virus affecting this country! #TrumpVirus Onto what little music news there is. Read on… If you haven’t already noticed, the internet has been flooded with livestream concerts by artists from those whose only performance experience is in their bedroom all the way to legends like Neil Young. -

Standard-Auswahl

Standard-Auswahl Nummer Titel Interpret Songchip 8001 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING Standard 10807 1000 MILES AWAY JEWEL Standard 8002 19-2000 GORILLAZ Standard 8701 20 YEARS OF SNOW REGINA SPEKTOR Standard 8004 25 MINUTES MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK Standard 8702 4 AM FOREVER LOSTPROPHETS Standard 8005 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN Standard 10808 4 TO THE FLOOR STARSAILOR Standard 8006 05:15:00 THE WHO Standard 8703 52ND STREET BILLY JOEL Standard 10050 93 MILLION MILES 30 SECONDS TO MARS Standard 8007 99 RED BALLOONS NENA Standard 8008 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS Standard 8704 A FOOL IN LOVE IKE & TINA TURNER Standard 10052 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY Standard 9009 A LIFE ON THE OCEAN WAVE P.D. Standard 9010 A LITTLE MORE CIDER TOO P.D. Standard 8009 A LONG DECEMBER COUNTING CROWS Standard 10053 A LONG WALK JILL SCOTT Standard 8010 A LOVER'S CONCERTO SARAH VAUGHAN Standard 9011 A MAIDENS WISH P.D. Standard 8011 A MILLION LOVE SONGS TAKE THAT Standard 8705 A NATURAL WOMAN ARETHA FRANKLIN Standard 10055 A PLACE FOR MY HEAD LINKIN PARK Standard 8012 A PLACE IN THE SUN STEVIE WONDER Standard 10809 A SONG FOR THE LOVERS RICHARD ASHCROFT Standard 10057 A SONG FOR YOU THE CARPENTERS Standard 9013 A THOUSAND LEAGUES AWAY P.D. Standard 10058 A THOUSAND MILES VANESSA CARLTON Standard 9014 A WANDERING MINSTREL P.D. Standard 8013 A WHITER SHADE OF PALE PROCOL HALUM Standard 8014 A WOMAN'S WORTH ALICIA KEYS Standard 8706 A WONDERFUL DREAM THE MAJORS Standard 10059 AARON'S PARTY (COME GET IT) AARON CARTER Standard 8016 ABC THE JACKSON 5 Standard 8017 ABOUT A GIRL NIRVANA Standard 10060 ACCIDIE CAPTAIN Standard 10061 ACHY BREAKY HEART BILLY RAY CYRUS Standard 10062 ADRIENNE THE CALLING Standard 10063 AFTER ALL AL JARREAU Standard 8019 AFTER THE LOVE HAS GONE EARTH, WIND & FIRE Standard 10064 AFTERNOONS & COFFEESPOONS CRASH TEST DUMMIES Standard 8020 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ Standard 10810 AGAIN AND AGAIN THE BIRD AND THE BEE Standard 10066 AGE AIN'T NOTHING BUT A AALIYAH Standard 8707 NUMAIN'TBE MIRSBE HAVIN' HANK WILLIAMS, JR. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Lecture in English (PDF)

1 L'Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze, avec Claire Parnet Directed by Pierre-André Boutang (1996) Translation & Notes: Charles J. Stivale Credits (shown at the end of each tape): Conversation: Claire Parnet Direction: Pierre-André Boutang, Michel Pamart Image: Alain Thiollet Sound: Jean Maini Editing: Nedjma Scialom Sound Mix: Vianney Aubé, Rémi Stengel Images from Vincennes: Marielle Burkhalter --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Translated and edited by Charles J. Stivale --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prelude \1 A short description of the trailer and then of the interview "set" is quite useful: the black and white trailer over which the title, then the director’s credit are shown, depicts Deleuze lecturing to a crowded, smoky seminar, his voice barely audible over the musical accompaniment. The subtitle, “Université de Vincennes, 1980,” appears briefly at the lower right, and Deleuze’s desk is packed with tape recorders. A second shot is a close-up of Deleuze chatting with the students seated closest to him. Then another shot shows students in the seminar listening intently, most of them (including a young Claire Parnet in profile) smoking cigarettes. The final shot again shows Deleuze lecturing from his desk at the front of the seminar room, gesticulating as he speaks. The final gesture shows him placing his hand over his chin in a freeze-frame, punctuating the point he has just made. As for the setting in Deleuze’s apartment during the interview, the viewer sees Deleuze seated in front of a sideboard over which hangs a mirror, and opposite him sits Parnet, smoking constantly throughout. On the dresser to the right of the mirror is his trademark hat perched on a hook.