Related Activities (Part 5: Beyond Basic Preservation)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section Ii Inventory and Analysis

SECTION II INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS II. INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS A. Overview and Summary The Village of Saugerties has a little over four miles of waterfront 1.5 miles on the Hudson River and about 1.3 miles on either side of the Esopus Creek (from the lighthouse to the dam). The proposed Coastal Area Boundary extends an average of some 2,000 feet inland from the shoreline, although the depth of the area varies widely. The land area withip the coastal boundary, including the Esopus Creek and the wetlands at its mouth, totals approximately 500 acres. This relatively small coastal area includes a wide variety of land uses and physical features (see Map No. 3 - Reconnaissance). The Hudson River waterfront and the mouth of the Esopus Creek contain low density "estate type" residential a,reas and several large freshwater wetlands. The long straight channel starting at the abandoned lighthouse, where the Creek empties into the Hudson (see Photo No.2), is lined with relatively new, single family homes in addition to the few water dependent uses on the creek - a boat club, two commercial marinas and a U.S. Coast Guard Station (see Photo Nos •. 3 and 4). The Creek then takes a large horseshoe curve before the navigable portion ends at the dam (see Photo No.5). On the south, inside shore, are the ruins and vestiges of the Village's extensive indus trial past (see Photo No.6) including a raceway which once carried water to power the substantial industrial complex. On the north side are steep, rocky slopes, except for one gap which contains several houses and the'Village's sewage treatment plant (see Photo No.7). -

Appendix: Women Who Kept the Lights, 1776- 1947

This PDF of the appendix of Women Who Kept the Lights was created for www. lighthousehistory.info and is copyrighted material Appendix: Women Who Kept the Lights, 1776- 1947 This appendix was initially based on the handwritten registers of lighthouse keepers and their assistants reproduced in National Archives microfilm publication no. M1373.1 Some of the handwriting in these registers was very difficult to read; for example, Ellis was read as Ellie, but corrected through correspondence. Nor could first names like Darrell be easily identified as masculine or feminine. This appendix does not include dozens of women who served for a period of months (less than a year) after a father’s or husband’s death, while they waited for the arrival of a new keeper. Nor does it include the hundreds of women who served as assistant keepers. Several of the women whose careers are detailed in this book, however, served as both assistant keepers and keepers. Two in particular—Kathleen Moore and Ida Lewis—began keeping the lights while still in their teens and spent most of their lives in lighthouses. Because their experiences as assistants have been recorded, those years are included in their chapters. The total number of women serving as principal keepers for more than a year and included in this appendix is 142; some have been added for the period both before and after the volumes listed above were recorded and were found in subsequent research; however, we do not include women who were assigned keeper duties after lighthouses were transferred to the U.S. -

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

Garden State Preservation Trust

COVERCOVERcover Garden State Preservation Trust DRAFT Annual Report INCOMPLETE FISCAL YEAR 2011 This is a director's draft of the proposed FY2011 Annual Report of the Garden State Preservation Trust. This draft report is a work-in- progress. This draft has neither been reviewed nor approved by the chairman or members of the GSPT board. The director's draft is being posted in parts as they are completed to make the information publicly available pending submission, review and final approval by the GSPT board. Garden State Preservation Trust Fiscal Year 2011 DRAFT Annual Report This is the Annual Report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for the Fiscal Year 2011 from July 1, 2010 to June 30, 2011. It has always been goal and mission of the Garden State Preservation Trust to place preservation first. This report reflects that priority. The most common suggestion concerning prior annual reports was to give more prominent placement to statistics about land preservation. This report is structured to place the preservation data first and to provide it in unprecedented detail. Information and financial data concerning GSPT financing, recent appropriations and agency operations are contained in the chapters which follow the acreage tables. This is to be construed as the full annual report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for the 2011 Fiscal Year in compliance with P.L. 1999 C.152 section 8C-15. It is also intended to be a comprehensive summary of required financial reporting from FY2000 through FY2011. This document updates the financial and statistical tables contained in prior annual reports. -

Countyhistory

CMC Heritage brochure-2018a WEB_Layout 1 10/7/18 10:40 AM Page 1 Cape May Annual Events Cultural and county, N J SUNDAY BEFORE MOTHER’S DAY: Partners in Preservation Annual Plant Sale: at the Hereford Inlet Historical Attractions Lighthouse, North Wildwood. www.wildwoodnjhistory.com MAY: 3RD SATURDAY Cape Maycounty, NJ Cultural and Armed Forces Day at the Tower: Cape May Point. www.capemaymac.org MEMORIAL DAY: Cape May County’s heritage lies within the farming and fishing Memorial Day ceremonies, free lunch: at the Stone Harbor Life Saving industry, with settlers coming to the area more than 325 years ago to Historical Attractions Station/American Legion, Stone Harbor. www.stephencludlampost331.org fish the waters of the Atlantic Ocean and the Delaware Bay and farm the J U N E 1 4 T H : fertile soil of the mainland. Today tourism drives the economy and Flag Day Ceremony: Stone Harbor Life Saving Station/American Legion, fishing and farming remain part of the appeal that brings visitors Stone Harbor. www.stephencludlampost331.org back year after year. Learn about the rich history of Cape May County JUNE: 2ND SATURDAY through the many museums and historic sites listed in this brochure. Olde House Tour: Avalon Historical Society, Avalon. www.Avalonhistorycenter.org Funding has been made possible in part by the new Jersey historical commission, JUNE: 3RD SATURDAY department oF state. Annual Antiques and Craft Fair: Greater Cape May Historical Society, Wilbraham Park, West Cape May. www.capemayhistory.org JULY: 3RD SATURDAY Annual Clamshell Pitching Tournament: Avalon History Center, Avalon. www.Avalonhistorycenter.org AUGUST 7TH: National Lighthouse Day: Celebrate at these lighthouses: Hereford Inlet Lighthouse, North Wildwood. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

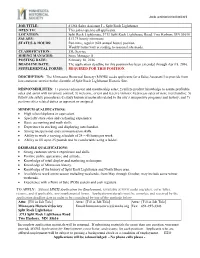

Split Rock Lighthouse OPEN TO: This Job Is Open to All Applicants

JOB ANNOUNCEMENT JOB TITLE: #1264 Sales Assistant I – Split Rock Lighthouse OPEN TO: This job is open to all applicants. LOCATION: Split Rock Lighthouse, 3713 Split Rock Lighthouse Road, Two Harbors, MN 55616 SALARY: $13.73 hourly minimum STATUS & HOURS: Part-time, regular (624 annual hours) position. Weekly hours vary according to seasonal site needs. CLASSIFICATION: 55L Service HIRING MANAGER: Store Manager II POSTING DATE: February 10, 2016 DEADLINE DATE: The application deadline for this position has been extended through April 8, 2016. SUPPLEMENTAL FORMS: REQUIRED FOR THIS POSITION. DESCRIPTION: The Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) seeks applicants for a Sales Assistant I to provide front line customer service to the clientele of Split Rock Lighthouse Historic Site. RESPONSIBILITIES: 1) process admission and membership sales; 2) utilize product knowledge to assure profitable sales and assist with inventory control; 3) welcome, orient and receive visitors; 4) process sales of store merchandise; 5) follow site safety procedures; 6) study historical materials related to the site’s interpretive programs and history; and 7) perform other related duties as apparent or assigned. MINIMUM QUALIFICATIONS: High school diploma or equivalent. Specialty store sales and cashiering experience. Basic accounting and math skills. Experience in stocking and displaying merchandise. Strong interpersonal and communication skills. Ability to work a varying schedule of 24 – 40 hours per week. Ability to lift up to 25 pounds and be comfortable using a ladder. DESIRABLE QUALIFICATIONS: Strong customer service experience and skills. Positive public appearance and attitude. Knowledge of retail display and marketing techniques. Knowledge of Minnesota history. Knowledge of the history of Split Rock Lighthouse and North Shore area. -

Ocean City, NJ on in Real Estate the Map for More Than Sales and Rentals Over 10,000 Leases Per Year 43 Years

US POSTAGE PAID MAIL PERFECT Official Visitors Guide 2011 PRSRT STD BERGER OCEAN CITY New Jersey Ocean City Regional REALTY Chamber of Commerce www.oceancityvacation.com Leon K. Grisbaum - Owner 1-800-BEACH-NJ Mark Soifer, Ocean City’s Leader “America’s Greatest Ocean City Publicist Family Resort” Putting Ocean City, NJ on In Real Estate the map for more than Sales and Rentals Over 10,000 leases per year 43 years. Over 2,500 rental properties PLUS Follow his weekly column Largest # of Full-Time every Thursday on Rental/Sale Agents and Office Support Staff www.OceanCityVacation.com VISIT ONE OF OUR 4 OFFICES 3160 Asbury Ave. 133 S. Shore Rd. Ocean City, NJ Marmora, NJ 1-888-399-0076 1-609-390-9300 17th & The Boardwalk 55th & Haven Ave. Over 30 Rides! OCC11 Ocean City, NJ Ocean City, NJ 1515 FREEFREE RideRide TicketsTickets plus 1-888-579-0095 1-800-399-3484 Money Saving Coupons with purchase of FAMILY BOOK • Offer good until 10/10/11 Or Online at Our Tickets Playland’sPlayland’s CastawayCastaway CoveCove www.bergerrealty.com NEVER EXPIRE!!! 10th & Boardwalk • OCNJ • oceancityfun.com MUST PRESENT THIS COUPON FOR BONUS OFFER • CANNOT BE COMBINED WITH ANY OTHER OFFER Photography - Don Kravitz Don - Photography POINTS OF INTEREST 1 Airport 2 Bayside Center, 520 Bay Avenue 3 Boardwalk 4 Boat Ramp, Tennessee Avenue 5 City Hall Annex, 901 Asbury Avenue 6 City Hall, 861 Asbury Avenue 7 Cultural-Aquatic & Fitness Center, 1701 Simpson Library, Art Center, Historical Museum 8 Golf Course, 2600 Bay Avenue 9 Humane Society, 1 Shelter Rd 10 Information Centers a. -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund January 2011 Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director . 1 Overview . 2 Feature Stories on Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF) History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Initiatives Inspiring Students and Teachers . 6 Investing in People and Communities . 10 Dakota and Ojibwe: Preserving a Legacy . .12 Linking Past, Present and Future . .15 Access For Everyone . .18 ACHF History Appropriations Language . .21 Full Report of ACHF History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Statewide Initiatives Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 23 Statewide Historic Programs . 75 Statewide History Partnership Projects . 83 “Our Minnesota” Exhibit . .91 Survey of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 92 Minnesota Digital Library . 93 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $18,400 Upon request the 2011 report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of the 2011 report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2011 report is available at the Society’s website: www.mnhs.org/legacy. COVER IMAGES, CLOCKWIse FROM upper-LEFT: Teacher training field trip to Oliver H. -

Fire Island Light Station

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES--COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Fire Island Light Station _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN Bay Shore 0.1. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York 36 Suffolk HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT -XPUBLIC OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL XPARK _XSTRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS iLYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service, Morth Atlantic Region STREET & NUMBER 15 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Massachusetts COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Land Acquisition Division, National Park Service, North Atlantic CITY. TOWN STATE Boston, Massachusetts TITLE U.S. Coast Guard, 3d Dist., "Fire Island Station Annex" Civil Plot Plan 03-5523 DATE 18 June 1975, revised 8-7-80 .^FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS- Nationa-| park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office CITY, TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS . X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_____ X.FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Fire Island Light Station is situated 5 miles east of the western end of Fire Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island. It consists of a lighthouse and an adjacent keeper's quarters sitting on a raised terrace. -

Lighthouses – Clippings

GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION MILWAUKEE PUBLIC LIBRARY/WISCONSIN MARINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY MARINE SUBJECT FILES LIGHTHOUSE CLIPPINGS Current as of November 7, 2018 LIGHTHOUSE NAME – STATE - LAKE – FILE LOCATION Algoma Pierhead Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan - Algoma Alpena Light – Michigan – Lake Huron - Alpena Apostle Islands Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Apostle Islands Ashland Harbor Breakwater Light – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Ashland Ashtabula Harbor Light – Ohio – Lake Erie - Ashtabula Badgeley Island – Ontario – Georgian Bay, Lake Huron – Badgeley Island Bailey’s Harbor Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bailey’s Harbor Range Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bala Light – Ontario – Lake Muskoka – Muskoka Lakes Bar Point Shoal Light – Michigan – Lake Erie – Detroit River Baraga (Escanaba) (Sand Point) Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Sand Point Barber’s Point Light (Old) – New York – Lake Champlain – Barber’s Point Barcelona Light – New York – Lake Erie – Barcelona Lighthouse Battle Island Lightstation – Ontario – Lake Superior – Battle Island Light Beaver Head Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Beaver Island Beaver Island Harbor Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – St. James (Beaver Island Harbor) Belle Isle Lighthouse – Michigan – Lake St. Clair – Belle Isle Bellevue Park Old Range Light – Michigan/Ontario – St. Mary’s River – Bellevue Park Bete Grise Light – Michigan – Lake Superior – Mendota (Bete Grise) Bete Grise Bay Light – Michigan – Lake Superior -

The Long Island Historical Journal

THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL United States Army Barracks at Camp Upton, Yaphank, New York c. 1917 Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 Starting from fish-shape Paumanok where I was born… Walt Whitman Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Numbers 1-2 Published by the Department of History and The Center for Regional Policy Studies Stony Brook University Copyright 2004 by the Long Island Historical Journal ISSN 0898-7084 All rights reserved Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life The editors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Office of the Provost and of the Dean of Social and Behavioral Science, Stony Brook University (SBU). We thank the Center for Excellence and Innovation in Education, SBU, and the Long Island Studies Council for their generous assistance. We appreciate the unstinting cooperation of Ned C. Landsman, Chair, Department of History, SBU, and of past chairpersons Gary J. Marker, Wilbur R. Miller, and Joel T. Rosenthal. The work and support of Ms. Susan Grumet of the SBU History Department has been indispensable. Beginning this year the Center for Regional Policy Studies at SBU became co-publisher of the Long Island Historical Journal. Continued publication would not have been possible without this support. The editors thank Dr. Lee E. Koppelman, Executive Director, and Ms. Edy Jones, Ms. Jennifer Jones, and Ms. Melissa Jones, of the Center’s staff. Special thanks to former editor Marsha Hamilton for the continuous help and guidance she has provided to the new editor. The Long Island Historical Journal is published annually in the spring.