Dr John Glen Interviewed by Paul Merchant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Landscapes

JANUARY 2013 Arkansas WINTER Landscapes Thanks from the Big Apple It’s a Family Thing at The Green Store On the shOres Of table rOck lake in sOuthwest MissOuri January through February 2013 FALLS LODGE DOUBLE QUEEN ROOM Double Queen Rooms in Falls Lodge feature a balcony or a patio, a Jacuzzi bath and Sleep Experience bedding. PRIVATE ONE ROOM LOG CABIN OR FALLS LODGE DELUXE KING ROOM Choose from a Private One Room Log Cabin with a wood-burning fireplace, a private deck, and an outdoor grill or a Deluxe King Room on the top floor of Falls Lodge, featuring a gas fireplace and a balcony overlooking the lake. Either accommodation will spoil you with the Sleep Experience bedding and a jetted tub. *VALID SUNDAY THROUGH THURSDAY ONLY. Not valid on current reservations, holidays or Limited groups availability. over 10. BigCedar.com 1.800.225.6343 RA01132 JANUARY 2013 CONTENTS JANUARY 2013 10 PHOTO BY GAR Y B features 32 EAN 10 Arkansas Winter Landscapes in every issue Arkansas wilderness photographer, Tim Ernst, pays homage to this season with some Arkansas winter 4 Editor’s Letter landscapes. 6 Currents 18 Hammerschmidt Receives Sidney S. McMath Public Service 7 Trivia Leadership Award 24 Capitol Buzz 20 Thanks from the Big Apple New Yorker shows 26 Doug Rye Says gratitude to Arkansas linemen 30 Healthy Living 32 Cooking with Joy 36 Reflections 38 Crossword Puzzle on the cover 39 Scenes from the Past Frozen Glory Hole 40 Let’s Eat This formation, built from layer upon layer of ice, took at least a week to develop. -

Terrestrial Hibernation in the Northern Cricket Frog, Acris Cnepitans

1240 Terrestrial hibernation in the northern cricket frog, Acris cnepitans Jason T. hwin, Jon P. Gostanzo, and Rlchard E. Lee, Jr. Abstract: We used laboratory experiments and field observations to explore overwintering in the northern cricket frog, Acris crepitans, in southern Ohio and Indiana. Cricket frogs died within 24 h when submerged in simulated pond warer that was anoxic or hypoxic, but lived 8-10 days when the water was oxygenatedinitially. Habitat selectionexperiments indicated that cricket frogs prefer a soil substrate to water as temperature decreasesfrom 8 to 2"C. These data suggested that cricket frogs hibernate terrestrially. However, unlike sympatric hylids, this species does not tolerate extensive freezing: only 2 of 15 individuals survived freezing in the -0.8 to -2.6"C range (duration 24-96 h). Cricket fiogs supercooledwhen dry (mean supercoolingpoint -5.5"C; range from -4.3 to -6.8'C), but were easily inoculated by external ice at temperatures between -0.5 and -0.8"C. Our data suggested that cricket frogs hibernate terrestrially but are not freeze tolerant, are not fossorial, and are incapable of supercooling in the presence of external ice. Thus we hypothesized that cricket frogs must hibernate in terrestrial sites that adequately protect against freezing. Indeed, midwinter surveys revealed cricket frogs hibernating in crayfish burrows and cracks of the pond bank, where wet soils buff'ered against extensive freezing of the soil. R6sum6 : Nous avons proc6d6 i des expdriences en laboratoire et A des observations sur le terrain pour 6tudier le sort de la Rainettegrillon, Acris crepitans,en hiver dans le sud de I'Ohio et de I'Indiana. -

Quantification of Ikaite in Antarctic Sea

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | The Cryosphere Discuss., 6, 505–530, 2012 www.the-cryosphere-discuss.net/6/505/2012/ The Cryosphere doi:10.5194/tcd-6-505-2012 Discussions © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal The Cryosphere (TC). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in TC if available. Quantification of ikaite in Antarctic sea ice M. Fischer1,6, D. N. Thomas2,3, A. Krell1, G. Nehrke1, J. Gottlicher¨ 4, L. Norman2, C. Riaux-Gobin5, and G. S. Dieckmann1 1Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Reserach, Bremerhaven, Germany 2Ocean Sciences, College of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Menai Bridge, UK 3Marine Centre, Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE), Helsinki, Finland 4Institute of Synchrotron Radiation (ISS), Synchrotron Radiation Source ANKA, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany 5USR3278, CRIOBE, CNRS-EPHE, Perpignan, France 6Faculty of Biology and Chemistry, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany Received: 18 January 2012 – Accepted: 25 January 2012 – Published: 3 February 2012 Correspondence to: M. Fischer (michael.fi[email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 505 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract Calcium carbonate precipitation in sea ice can increase pCO2 during precipitation in winter and decrease pCO2 during dissolution in spring. CaCO3 precipitation in sea ice is thought to potentially drive significant CO2 uptake by the ocean. However, little is 5 known about the quantitative spatial and temporal distribution of CaCO3 within sea ice. This is the first quantitative study of hydrous calcium carbonate, as ikaite, in sea ice and discusses its potential significance for the carbon cycle in polar oceans. -

Working Pack Dog Titles 2017-0119

Working Pack Dog issued number registeredname owners regnum sire sireregnum dam damregnum 1 Shadak’s Sastan Taka Keith & Lynne Hurrell WC786190 Lobito's Caballero of Kiska WC257803 Shadak's Shukeenyuk WB579440 2 Shadak’s Tich-A-Luk Keith & Lynne Hurrell 3 Shadak’s Artic Sonrise Keith & Lynne Hurrell WB650563 Pak N Pulls Kingak WA764822 Pak N Pulls Arctic Shadow WA524342 4 Arken’s Nakina Cheryll Arkins 5 Shadak’s Wicked Winter Keith & Lynne Hurrell WD543192 Witch 6 Czarina Anastasia Nicolle Pat Paulding WD625393 Wyvern Alyeska Arkah of Jo- WB547353 Wyvern's Heather WC990172 Jan 7 Kamai’s Alaluk Of Inuit Ralph Coppola WD686604 Inuit's Driftwood WD252511 Kamai's Artica of Inuit WC738866 8 Suak’s Brite Artic Dawn Paula & Louis Perdoni WE020543 Wyvern's Invictus WD609383 Suak's Aksoah of Brandy WD222764 9 Sno King’s Northern Light Jackai Szuhai WD932145 Tigara's Apollo of Totemtok WC367473 Tamerak's Mist of Cougar Cub WC980864 10 Nicole Ohtahyon Jackai Szuhai WC010823 Athabascan King WB386373 Nicole of Athabasca WB495979 11 Storm King Of Berkeley Gale Castro WE266354 12 Maska Bull Of Rushing Waters Jeff Rolfson WD233138 Gypsy King WC791246 Cricket Lady Under the Pine WC423794 13 Avalanche At Snow Castle Helen Brockmeyer WD598136 Aristeed's Frost Shadow WB496698 Storm Kloud's Happy Nequivik WC510192 14 Maska’s Sure-Foot Sheba Jeff Rolfson WE707239 Maska Bull of Rushing Waters WD233138 Beauty Queen of Swamp WD701391 Hollow 15 Hi-De-Ho’s Royal Heritage Of Sue Worley WE333340 Northwood's Lord Kipnuk WB475489 Eldor's Starr Von Hi-De-Ho WD490983 -

Park District News ………..…2 Naturalist Programs ……… 3-4

Park District News ………..…2 What’s Inside Naturalist Programs ……… 3-4 Christmas Tree Recycling …...8 Luminary Walk ……………...5 Asian Longhorned Beetle …..9-10 Thank You …………………..6 Rental Facilities ……………...11 Fall Festival ……………….....7 Park Information ……………12 Luminary Walk page 5 Park District News Chris Clingman, Director At Pattison Park you may have noticed that several large trees have been removed. These are all ash trees that have been infested by the Emerald Ash Borer. Once they infest a tree it takes about 5 years to completely kill the tree. Duke Energy contacted the Park District about several of these trees along power lines that run parallel or through park properties. In order to prevent the trees from dropping branches on the power lines, Duke has started to remove the infested ash trees. This will help prevent power outages in the area. The Park District will use the wood at Pattison Park for our maple syrup programs. Moving the wood to other locations could be very destructive, as it would help speed the spread of this destructive pest. For more information on Emerald Ash Borer visit http://ashalert.osu.edu/ Elsewhere in this newsletter you will find information on the Asian Longhorned Beetle. This pest attacks 13 different genera of trees with maples being its preferred host. The primary infestation is in the village of Bethel and Tate Township, but it has also been found in small areas of Stonelick and Monroe Townships. Both of those infestations can be linked to firewood being moved from the Bethel area to those townships. For more information on the Asian Longhorned Beetle visit www.beetlebusters.info This winter the Chilo Lock 34 Visitor Center and Museum will be closed to help save on staff and utility costs. -

(Antarctica) Glacial, Basal, and Accretion Ice

CHARACTERIZATION OF ORGANISMS IN VOSTOK (ANTARCTICA) GLACIAL, BASAL, AND ACCRETION ICE Colby J. Gura A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2019 Committee: Scott O. Rogers, Advisor Helen Michaels Paul Morris © 2019 Colby Gura All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Scott O. Rogers, Advisor Chapter 1: Lake Vostok is named for the nearby Vostok Station located at 78°28’S, 106°48’E and at an elevation of 3,488 m. The lake is covered by a glacier that is approximately 4 km thick and comprised of 4 different types of ice: meteoric, basal, type 1 accretion ice, and type 2 accretion ice. Six samples were derived from the glacial, basal, and accretion ice of the 5G ice core (depths of 2,149 m; 3,501 m; 3,520 m; 3,540 m; 3,569 m; and 3,585 m) and prepared through several processes. The RNA and DNA were extracted from ultracentrifugally concentrated meltwater samples. From the extracted RNA, cDNA was synthesized so the samples could be further manipulated. Both the cDNA and the DNA were amplified through polymerase chain reaction. Ion Torrent primers were attached to the DNA and cDNA and then prepared to be sequenced. Following sequencing the sequences were analyzed using BLAST. Python and Biopython were then used to collect more data and organize the data for manual curation and analysis. Chapter 2: As a result of the glacier and its geographic location, Lake Vostok is an extreme and unique environment that is often compared to Jupiter’s ice-covered moon, Europa. -

Cricket Smart Resources

IT’S A GLOBAL GAME CURRICULUM-ALIGNED RESOURCES FOR YEAR 1–8 TEACHERS EXTERNAL LINKS TO WEBSITES New Zealand Cricket does not accept any liability for the accuracy of information on external websites, nor for the accuracy or content of any third-party website accessed via a hyperlink from the www.blackcaps.co.nz/schools website or Cricket Smart resources. Links to other websites should not be taken as endorsement of those sites or of products offered on those sites. Some websites have dynamic content, and we cannot accept liability for the content that is displayed. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For their support with the development of the Cricket Smart resources, New Zealand Cricket would like to thank: • the New Zealand Government • Sport New Zealand • the International Cricket Council • the ICC Cricket World Cup 2015 • Cognition Education Limited. Photograph on the cover Supplied by ICC Cricket World Cup 2015 Photographs and images on page 2 © Dave Lintott / www.photosport.co.nz 7 (cricket equipment) © imagedb.com/Shutterstock, (bat and ball) © imagedb.com/Shutterstock, (ICC Cricket World Cup Trophy) supplied by ICC Cricket World Cup 2015, (cricket ball) © Robyn Mackenzie/Shutterstock 11 © ildogesto/Shutterstock 12 © imagedb.com/Shutterstock 13 By Mohamed Nanbhay Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) 14 © www.photosport.co.nz 15 Supplied by ICC Cricket World Cup 2015 16 © John Cowpland / www.photosport.co.nz 17 © Anthony Au-Yueng / www.photosport.co.nz 18 © Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock, 19 © VladimirCeresnak/Shutterstock © New Zealand Cricket Inc. No part of this material may be used for commercial purposes or distributed without the express written permission of the copyright holders. -

East Antarctic Sea Ice in Spring: Spectral Albedo of Snow, Nilas, Frost Flowers and Slush, and Light-Absorbing Impurities in Snow

Annals of Glaciology 56(69) 2015 doi: 10.3189/2015AoG69A574 53 East Antarctic sea ice in spring: spectral albedo of snow, nilas, frost flowers and slush, and light-absorbing impurities in snow Maria C. ZATKO, Stephen G. WARREN Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Spectral albedos of open water, nilas, nilas with frost flowers, slush, and first-year ice with both thin and thick snow cover were measured in the East Antarctic sea-ice zone during the Sea Ice Physics and Ecosystems eXperiment II (SIPEX II) from September to November 2012, near 658 S, 1208 E. Albedo was measured across the ultraviolet (UV), visible and near-infrared (nIR) wavelengths, augmenting a dataset from prior Antarctic expeditions with spectral coverage extended to longer wavelengths, and with measurement of slush and frost flowers, which had not been encountered on the prior expeditions. At visible and UV wavelengths, the albedo depends on the thickness of snow or ice; in the nIR the albedo is determined by the specific surface area. The growth of frost flowers causes the nilas albedo to increase by 0.2±0.3 in the UV and visible wavelengths. The spectral albedos are integrated over wavelength to obtain broadband albedos for wavelength bands commonly used in climate models. The albedo spectrum for deep snow on first-year sea ice shows no evidence of light- absorbing particulate impurities (LAI), such as black carbon (BC) or organics, which is consistent with the extremely small quantities of LAI found by filtering snow meltwater. -

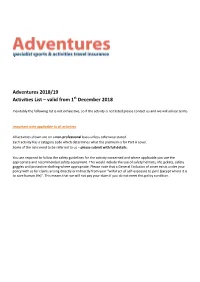

Activities List – Valid from 1St December 2018

Adventures 2018/19 Activities List – valid from 1st December 2018 Inevitably the following list is not exhaustive, so if the activity is not listed please contact us and we will advise terms. Important note applicable to all activities All activities shown are on a non-professional basis unless otherwise stated. Each activity has a category code which determines what the premium is for Part A cover. Some of the risks need to be referred to us – please submit with full details. You are required to follow the safety guidelines for the activity concerned and where applicable you use the appropriate and recommended safety equipment. This would include the use of safety helmets, life jackets, safety goggles and protective clothing where appropriate. Please note that a General Exclusion of cover exists under your policy with us for claims arising directly or indirectly from your "wilful act of self-exposure to peril (except where it is to save human life)". This means that we will not pay your claim if you do not meet this policy condition. Adventures Description category Abseiling 2 Activity Centre Holidays 2 Aerobics 1 Airboarding 5 Alligator Wrestling 6 Amateur Sports (contact e.g. Rugby) 3 Amateur Sports (non-contact e.g. Football, Tennis) 1 American Football 3 Animal Sanctuary/Refuge Work – Domestic 2 Animal Sanctuary/Refuge Work – Wild 3 Archery 1 Assault Course (Must be Professionally Organised) 2 Athletics 1 Badminton 1 Bamboo Rafting 1 Banana Boating 1 Bar Work 1 Base Jumping Not acceptable Baseball 1 Basketball 1 Beach Games 1 Big -

Zuoz Zeitung 2018

JAHRGANG // 77. ZUOZZEITUNG 01–2018 01–2018 NEUER REKTOR CRICKET ON ICE ZUOZ WINTER GAMES MEET THE REGIONAL- CHALLENGE 2018 ZUOZ CLUB GRUPPEN Dr. Christoph Wittmer Lyceum Alpinum’s Outdoor adventure, Gelebte Tradition Graduating class News aus den stellt sich vor love for cricket community service & meets with Regionen activities the President SCHULE & INTERNAT 3 Editorial 4 Headmaster’s News 7 The IB Career-Related Programme 8 News from the College Counselling Office 9 Design Technology 10 Creative Writing Club 11 Investment and Leadership Day Editorial 12 Maturaarbeiten 2017/18 13 „Seit meiner Kindheit ist es mein Wunsch, einmal in der Automobilbranche tätig zu sein.“ 14 So Close, yet so Far Away 15 CAS Projects 2018 BEI UNS VERDIENT SOGAR 16 WEISSER RING Charity Gala 2018 18 Health Awareness News DER AUSBLICK FÜNF STERNE 19 Chesa Urezza: First Semester in the New House 20 Weekend Activities 23 Movember @ Lyceum Alpinum 24 The Zuoz Challenge Nirgendwo in St. Moritz sind die glitzernden PEOPLE Wir freuen uns sehr, Ihnen unseren neuen Rektor Dr. Christoph Bergseen und die schneebedeckten Berggipfel so 26 Herzlich Willkommen Familie Wittmer! Wittmer vorzustellen. Christoph Wittmer spricht über seinen Ideen unmittelbar zu erleben wie im Suvretta House. EVENTS und Ziele für das Lyceum Alpinum, die Herausforderungen in der Weitab von touristischer Hektik und inmitten einer 28 The First Winter Camp in Zuoz Bildungswelt und wie er die Schule in die Zukunft führen will. Le- 29 Unforgettable Summer in Zuoz sen Sie mehr zur Familie Wittmer auf Seite 26. Herzlich Willkom- herrlichen, natürlichen Parklandschaft geniessen 30 Vienna Ball 2018 Sie in einem stilvollen Ambiente 5-Sterne-Luxus mit men! Am diesjährigen WEF wurde wiederholt auf die zentrale Rolle SPORTS Resort-Charakter. -

Response to Review 1 V3

Dear Referee #1, Thank you very much for reviewing our manuscript and for your constructive and valuable comments and suggestions. In the following text, our response to your comments is given in blue, whereas the corresponding revisions in the main text are highlighted in red. 5 Gao et al present a study of ozone loss near the surface of an outdoor mesocosm sea ice facility in Winnipeg, Canada. The sea ice facility is unique and provides an opportunity to control the formation of the sea ice with complete exposure to the atmosphere, allowing ambient snow accumulation. The comparison of O3 levels during daytime for the UV-transmitting vs UV-blocking tubes is useful. The authors 10 attribute O3 loss at 10 cm above the sea ice surface (observed for the UV- transmitting but not UV-blocking, showing that this is a photochemical process) to reaction with bromine radicals based on their enhancement of seawater Br-, which then migrated into the snow above. My major comment is the lack of discussion of the role of NOx, which is known to be important in O3 and bromine chemistry, and 15 should be particularly important in this urban ambient study (see detailed comments below). This is particularly important because snow photochemical reactions produce NO, which can react with O3, and so disentangling this from reaction with Br is important to consider. Additionally, there is additional published literature, stated below, that is relevant and should be considered in this 20 manuscript. The role of NOx needs to be discussed in this study, as there is currently no mention of NOx in the paper. -

Post Event Release

Virender Sehwag and Mohammad Kaif announced the launch of St. Moritz Ice Cricket 2018 The inaugural edition to feature stalwarts of the game from across the globe New Delhi, 22nd Nov’17: The inaugural edition of the one of a kind St.Moritz Ice Cricket 2018 was announced today by legends of world cricket Virender Sehwag and Mohammad Kaif. The ex-cricketers shared they will be featuring in the inaugural edition, which will be held in St.Moritz, Switzerland on 8th and 9th February 2018. The group is a joined initiative of Vijay Singh, CEO, VJ Sports and Akhilesh Bahuguna, Director, All spheres Pvt.Ltd who accompanied the cricketers at the announcement Press Conference held on 22nd Nov' 17 at Hotel Pullman Aerocity, New Delhi. The unique two-day event set against the serene and breath-taking backdrop of the Swiss mountains will host two matches over two days. The two teams Badrutt’s Palace DIAMONDS and ROYALS will have star studded cricketers like Virender Sehwag, Mohammad Kaif, Mahela Jayawardene, Lasith Malinga, Shoaib Akhtar, Michael Hussey, Graeme Smith, Jacques Kallis, Daniel Vettori , Nathan Mcullum , Grant Elliot, Monty Panesar, Owais Shah, etc. The itinerary will also boast of a scenic tour of the Swiss local and a gala dinner where the fans will get a chance to rub shoulders with their favourite cricket personalities. Both the matches will be aired live on Sony ESPN on both its HD and SD feeds. The “Cricket on Ice” event was started by the British and has been played ever since for over 25 years on the St.