The Gumsucker at Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Feature, Place Or View Is Significant, Scenic Or Beautiful And

DPCD South West Victoria Landscape Assessment Study | CONSULTATION & COMMUNITY VALUES Landscape Significance Significant features identified were: Other features identified outside the study area were: ▪ Mount Leura and Mount Sugarloaf, outstanding ▪ Lake Gnotuk & Lake Bullen Merri, “twin” lakes, near volcanic features the study area’s edge, outstanding volcanic features Which feature, place or view is ▪ Mount Elephant of natural beauty, especially viewed from the saddle significant, scenic or beautiful and ▪ Western District Lakes, including Lake Terangpom of land separating them why? and Lake Bookar ▪ Port Campbell’s headland and port Back Creek at Tarrone, a natural waterway ...Lake Gnotuk and the Leura maar are just two examples of ▪ Where would you take a visitor to the outstanding volcanic features of the Western District. They give great pleasure to locals and visitors alike... show them the best view of the Excerpt from Keith Staff’s submission landscape? ▪ Glenelg River, a heritage river which is “pretty much unspoilt” ▪ Lake Bunijon, “nestled between the Grampians and rich farmland in the west, the marsh grasses frame the lake as a native bird life sanctuary” ▪ Botanic gardens throughout the district which contain “weird and wonderful specimens” ▪ Wildflowers at the Grampians The Volcanic Edge Booklet: The Mt Leura & Mt Sugarloaf Reserves, Camperdown, provided by Graham Arkinstall The Age article from 1966 about saving Mount Sugarloaf Lake Terangpom Provided by Brigid Cole-Adams Photo provided by Stuart McCallum, Friends of Bannockburn Bush, Greening Australia 10 © 2013 DPCD South West Victoria Landscape Assessment Study | CONSULTATION & COMMUNITY VALUES Other significant places that were identified were: Significant views identified were: ▪ Ditchfield Road, Raglan, an unsealed road through ▪ Views generally in the south west region ▪ Views from summits of volcanic craters bushland .. -

Objection to Scoria Quarry in Leura Maar

National Trust of Australia (Victoria) ABN 61 004 356 192 Tasma Terrace 23 December 2015 4 Parliament Place East Melbourne Victoria 3002 Greg Hayes Email: [email protected] Manager, Planning and Building Web: www.nationaltrust.org.au Corangamite Shire Council 181 Manifold Street T 03 9656 9800 F 03 9656 5397 Camperdown VIC 3260 Dear Mr Hayes, Re: Permit Application Number: PP2001/160.A Subject Land: Titan Willows’ Rock and Scoria Quarry, Princes Highway, Camperdown Lot 1 TP 667906P, Parish of Colongulac The National Trust has advocated for the protection of the Leura Maar, within which the subject land sits, since the 1970s. Mt Sugarloaf was saved from destruction in an unprecedented conservation battle - nowhere else in Australia had local people taken direct action to save a natural landmark. Local residents actually sat in front of a bulldozer during the battle to save the mount in 1969. The National Trust purchased the land in 1972 to prevent any further quarrying of the scoria and to guarantee the preservation of the remaining mount. Today Mt Sugarloaf is considered the best example of a scoria cone in the Western District, and is cared for by Corangamite Shire Council, the Management Committee and the Friends of Mt Leura. The Mount Leura complex is one of the largest maar and tuff volcanoes in Victoria, and is a prominent feature in the Kanawinka Geopark, part of the global geoparks network. Following this international recognition, the educational value of the Leura Maar is growing, thanks to local volunteers who have installed a geocaching trail and volcanic education centre in addition to the existing interpretive trails, signs and lookouts. -

Taylors Hill-Werribee South Sunbury-Gisborne Hurstbridge-Lilydale Wandin East-Cockatoo Pakenham-Mornington South West

TAYLORS HILL-WERRIBEE SOUTH SUNBURY-GISBORNE HURSTBRIDGE-LILYDALE WANDIN EAST-COCKATOO PAKENHAM-MORNINGTON SOUTH WEST Metro/Country Postcode Suburb Metro 3200 Frankston North Metro 3201 Carrum Downs Metro 3202 Heatherton Metro 3204 Bentleigh, McKinnon, Ormond Metro 3205 South Melbourne Metro 3206 Albert Park, Middle Park Metro 3207 Port Melbourne Country 3211 LiQle River Country 3212 Avalon, Lara, Point Wilson Country 3214 Corio, Norlane, North Shore Country 3215 Bell Park, Bell Post Hill, Drumcondra, Hamlyn Heights, North Geelong, Rippleside Country 3216 Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Highton, Marhsall, Mt Dunede, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds Country 3217 Deakin University - Geelong Country 3218 Geelong West, Herne Hill, Manifold Heights Country 3219 Breakwater, East Geelong, Newcomb, St Albans Park, Thomson, Whington Country 3220 Geelong, Newtown, South Geelong Anakie, Barrabool, Batesford, Bellarine, Ceres, Fyansford, Geelong MC, Gnarwarry, Grey River, KenneQ River, Lovely Banks, Moolap, Moorabool, Murgheboluc, Seperaon Creek, Country 3221 Staughtonvale, Stone Haven, Sugarloaf, Wallington, Wongarra, Wye River Country 3222 Clilon Springs, Curlewis, Drysdale, Mannerim, Marcus Hill Country 3223 Indented Head, Port Arlington, St Leonards Country 3224 Leopold Country 3225 Point Lonsdale, Queenscliffe, Swan Bay, Swan Island Country 3226 Ocean Grove Country 3227 Barwon Heads, Breamlea, Connewarre Country 3228 Bellbrae, Bells Beach, jan Juc, Torquay Country 3230 Anglesea Country 3231 Airleys Inlet, Big Hill, Eastern View, Fairhaven, Moggs -

Corangamite Heritage Study Stage 2 Volume 3 Reviewed

CORANGAMITE HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 2 VOLUME 3 REVIEWED AND REVISED THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Prepared for Corangamite Shire Council Samantha Westbrooke Ray Tonkin 13 Richards Street 179 Spensley St Coburg 3058 Clifton Hill 3068 ph 03 9354 3451 ph 03 9029 3687 mob 0417 537 413 mob 0408 313 721 [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION This report comprises Volume 3 of the Corangamite Heritage Study (Stage 2) 2013 (the Study). The purpose of the Study is to complete the identification, assessment and documentation of places of post-contact cultural significance within Corangamite Shire, excluding the town of Camperdown (the study area) and to make recommendations for their future conservation. This volume contains the Reviewed and Revised Thematic Environmental History. It should be read in conjunction with Volumes 1 & 2 of the Study, which contain the following: • Volume 1. Overview, Methodology & Recommendations • Volume 2. Citations for Precincts, Individual Places and Cultural Landscapes This document was reviewed and revised by Ray Tonkin and Samantha Westbrooke in July 2013 as part of the completion of the Corangamite Heritage Study, Stage 2. This was a task required by the brief for the Stage 2 study and was designed to ensure that the findings of the Stage 2 study were incorporated into the final version of the Thematic Environmental History. The revision largely amounts to the addition of material to supplement certain themes and the addition of further examples of places that illustrate those themes. There has also been a significant re-formatting of the document. Most of the original version was presented in a landscape format. -

Sendle Zones

Suburb Suburb Postcode State Zone Cowan 2081 NSW Cowan 2081 NSW Remote Berowra Creek 2082 NSW Berowra Creek 2082 NSW Remote Bar Point 2083 NSW Bar Point 2083 NSW Remote Cheero Point 2083 NSW Cheero Point 2083 NSW Remote Cogra Bay 2083 NSW Cogra Bay 2083 NSW Remote Milsons Passage 2083 NSW Milsons Passage 2083 NSW Remote Cottage Point 2084 NSW Cottage Point 2084 NSW Remote Mccarrs Creek 2105 NSW Mccarrs Creek 2105 NSW Remote Elvina Bay 2105 NSW Elvina Bay 2105 NSW Remote Lovett Bay 2105 NSW Lovett Bay 2105 NSW Remote Morning Bay 2105 NSW Morning Bay 2105 NSW Remote Scotland Island 2105 NSW Scotland Island 2105 NSW Remote Coasters Retreat 2108 NSW Coasters Retreat 2108 NSW Remote Currawong Beach 2108 NSW Currawong Beach 2108 NSW Remote Canoelands 2157 NSW Canoelands 2157 NSW Remote Forest Glen 2157 NSW Forest Glen 2157 NSW Remote Fiddletown 2159 NSW Fiddletown 2159 NSW Remote Bundeena 2230 NSW Bundeena 2230 NSW Remote Maianbar 2230 NSW Maianbar 2230 NSW Remote Audley 2232 NSW Audley 2232 NSW Remote Greengrove 2250 NSW Greengrove 2250 NSW Remote Mooney Mooney Creek 2250 NSWMooney Mooney Creek 2250 NSW Remote Ten Mile Hollow 2250 NSW Ten Mile Hollow 2250 NSW Remote Frazer Park 2259 NSW Frazer Park 2259 NSW Remote Martinsville 2265 NSW Martinsville 2265 NSW Remote Dangar 2309 NSW Dangar 2309 NSW Remote Allynbrook 2311 NSW Allynbrook 2311 NSW Remote Bingleburra 2311 NSW Bingleburra 2311 NSW Remote Carrabolla 2311 NSW Carrabolla 2311 NSW Remote East Gresford 2311 NSW East Gresford 2311 NSW Remote Eccleston 2311 NSW Eccleston 2311 NSW Remote -

Far East Gippsland Back Road Tours

Far East Gippsland Back Road Tours Returning to Clarkeville Rd turn left travel 0.9 kms Bendoc Historic Victoria Star Historic Mine Area. The Victoria Reef was originally worked in 1869. A rich lode was discovered in 1909. From Loop Drive 1911, this mine worked the highest-yielding reef in East Gippsland. Site features include mullock heaps, mine workings, machinery 6 foundations, remains of a battery and a portable steam engine. 4WD only. A rich history of alluvial Continue travelling south onto Clarkeville Rd travel 4.8 and reef gold mining. kms turn right onto Aspen’s Battery Tk travel 1.8 kms Jungle King Mine. This is a fine example of a quartz mining 4WD Classification: Easy shaft which commenced operation in 1889. Distance: 73 kms Duration: Half Day Delegate River Tunnel Returning onto Clarkeville Rd travel 4.8 kms turn right Further Information: onto Goonmirk Rocks Rd travel 4.9 kms Goonmirk Forests Notes: Bendoc Historic Loop Drive Rocks. A short walk to an interesting granite rocky outcrop Park Notes: Errinundra National Park featuring the ancient Mountain Plum Pine, Podocarpus lawrencei. Warnings: Log Truck Traffic. Seasonal Road Closure- Goonmirk Rd Continue travelling on Goonmirk Rocks Rd 1.2 kms turn Open mine shafts. right onto Gunmark Rd travel 6.4 kms Tea Tree Flat Picnic Area. On the Delegate River featuring sphagnum moss START at The Gap Scenic Reserve (Bonang Rd/Gap & heath plants. Rd intersection) 84 kms north of Orbost. Continue travelling on Gunmark Rd 4.3 kms turn left Follow Gap Rd travel 6.2 kms turn left onto Playgrounds onto Gap Rd travel 5.5 kms Gap Scenic Reserve. -

Far East Gippsland Back Road Tours

Far East Gippsland Back Road Tours [Optional Side Trip: Continue travelling 2.5 kms turn right travel 400m Frosty Hollow Campsite] Combienbar Turn north onto Hensleigh Creek Rd travel 9.2 kms East Errinundra Queensborough River Picnic Area. The Queensborough River flows north into the Delegate River which forms part of the upper Snowy River catchment before the 5 river flows westerly and then southerly to Bass Strait. 4WD only. A picturesque route to Continue travelling on Hensleigh Creek Rd 3.9 kms turn eastern Errinundra. left onto Goonmirk Rocks Rd travel 7.6 kms Goonmirk Rocks. A short walk amongst thickets of Mountain Plum-pine. 4WD Classification: Medium Distance: 111 kms continue travelling on Goonmirk Rocks Rd 1.2 kms Duration: Full Day or overnight View from Three Sisters Lookout turn left onto to Gunmark Rd travel 5.2 kms turn left Further Information: onto Errinundra Rd travel 1.9 kms turn left travel 50 m Forests Notes- Tennyson Picnic and Camping Area Errinundra Saddle. This picnic area is the main visitor focus Park Notes- Errinundra National Park for the park. Featuring a high quality interpretative display of the Warnings: Log Truck Traffic Park’s outstanding natural values and an easy 1 km rainforest walk. Seasonal road closures- Goonmirk Rd, Hensleigh Creek Rd, and Tennyson Tk. Continue travelling on Errinundra Rd 4.7 kms Mt Morris Tennyson Tk is steep, rocky and slippery requiring low range Picnic Area. Includes a 2 km 1 hr return walk to the granite 4WD with high ground clearance. A moderately difficult outcrop. Erridundra Plateau is a south east extension of the Monaro route to be travelled with care and by experienced drivers. -

Historic Places Special Investigation South-Western Victoria

1 LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL HISTORIC PLACES SPECIAL INVESTIGATION SOUTH-WESTERN VICTORIA FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS January 1997 This text is a facsimile of the former Land Conservation Council’s Historic Places Special Investigation South-Western Victoria Final Recommendations. It has been edited to incorporate Government decisions on the recommendations made by Orders in Council dated 11 and 24 June 1997 and subsequent formal amendments. Added text is shown underlined; deleted text is shown struck through. Annotations [in brackets] explain the origin of changes. 2 MEMBERS OF THE LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL D.S. Saunders, PSM, B.Agr.Sc.; Chairman. S. Dunn, B.Sc.(Hons.) Fisheries Science; Director, Fisheries, Department of Natural Resources and Environment. S. Harris, B.A., T.S.T.C. D. Lea, Dip.Mech.Eng; Executive Director, Minerals and Petroleum, Department of Natural Resources and Environment. R.D. Malcolmson, MBE, B.Sc., F.A.I.M., M.I.P.M.A., M.Inst.P., M.A.I.P. C.D. Mitchell, B.Sc.(Hons.), Ph.D. L.K. Murrell, B.A., Dip.Ed. R.P. Rawson, Dip.For.(Cres.), B.Sc.F.; Executive Director, Forestry and Fire, Department of Natural Resources and Environment. P.J. Robinson, OAM. M.W. Stone; Executive Director, Parks, Flora and Fauna, Department of Natural Resources and Environment. P.D. Sutherland, B.A., B.Sc.(Hons.); Executive Director, Agriculture and Catchment Management, Department of Natural Resources and Environment. ISBN: 0 7241 9290 5 3 CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROTECTION AND MANAGEMENT 18 General Public Land Management 18 Identification of New Historic Values 20 Managing Historic Places 21 Aspects of Use and Protection of Historic Places 31 General Recommendations on Specific Types of Historic Places 40 3. -

Southern Rivers Region

State of the catchments 2010 Riverine ecosystems Southern Rivers region State Plan target By 2015 there is an improvement in the condition of riverine ecosystems. Background The Southern Rivers region covers more than 30,000 km2, is bounded by Stanwell Park in the Illawarra to the north and includes all coastal catchments south to the Victorian border. The region has nine catchment areas including the Shoalhaven, Illawarra–Hacking, Clyde, Deua, Tuross, Bega and Towamba coastal catchments, and extends westwards to include the Snowy and Genoa catchments (Figure 1). This diverse region has many river systems that include the Minnamura, Kangaroo, Shoalhaven, Clyde, Deua, Tuross, Brogo, Moruya, Bega, Bemboka and Towamba rivers, all of which flow east to the coast; and the Genoa and Snowy rivers that originate in New South Wales and flow into lower catchments in Victoria. The largest catchment in the Southern Rivers region is the Shoalhaven, covering 7300 km2. The Shoalhaven River rises in the highlands of the Southern Tablelands at an altitude of 864 m above sea level and is 327 km in length. The Mongarlowe River is a major tributary of the Shoalhaven River and flows from the steep mountains of the Budawang Range, joining the main trunk of the Shoalhaven River near Braidwood. The southern section of the Shoalhaven River flows northwards before it merges with the southern flowing Kangaroo River and then flows east. The Kangaroo River and some of its tributaries fall rapidly downstream through gorge country onto alluvial plains near Nowra. Downstream of the gorge country near the confluence of the Kangaroo River with the Shoalhaven River, the river enters Tallowa Dam, which supplies water to Sydney and the Shoalhaven region. -

The Gauss-Krueger Projection

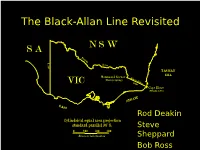

The Black-Allan Line Revisited Rod Deakin Steve Sheppard Bob Ross THE BLACK-ALLAN LINE What sort of line was it? The Act of British Parliament 1850 separating Victoria from New South Wales describing the boundaries of the new state, said in part: “…and bounded on the North and North-east by a straight Line drawn from Cape Howe to the nearest source of the River Murray, …” The Victorian Trigonometric survey was extended into the district of the north-east border and some time prior to 1869, Robert L. J. Ellery (Superintendent of the Victorian Geodetic Survey) met P. F. Adams (NSW Surveyor General) on the beach at Cape Howe and marked a point (Conference Point) as being an acceptable terminal of the border. At the end of 1869, surveyor Alexander Black had located the spring that was the most easterly source of the Murray. The terminal points were connected to the trigonometric survey and the “straight line” computed; marking of the line commenced in April 1870. Surveyor Black marked the easterly part from the Spring to a peg placed on the banks of the Delegate River. Surveyor Alexander Charles Allan marked the remaining 2/3 from the peg to the coast. Surveyor William Turton assisted both Black and Allan. Black’s trigonometric scheme The border survey finished in March 1872 and Allan’s line produced passed within 16.8 feet of the original pile (Conference Point). This was a remarkable surveying feat. The expenditures incurred by the three survey parties (Black’s, Allan’s and Turton’s) amounted to £4822-7-11. -

Errinundra National Park Is Unique in That It Offers Forests Ancient Outcrops the Monaro Tablelands

Errinundra National Park Visitor Guide Errinundra National Park is one of East Gippsland’s most outstanding natural areas, protecting Victoria’s largest stand of rainforest and age old tall eucalypt forests. The park now covers 39,870 hectares extending from Mt Ellery across the Errinundra Plateau, which rises more than 1000 metres above sea level, to the Coast Range. Location and access Remnants and history Errinundra National Park is 373 km east of The plateau was linked to ancient trails and Melbourne via the Princes Highway. The two main meeting places for local Aboriginal tribes. approaches are: European history is evident here from derelict notes mine shafts, old fence lines and machinery From the west via the Bonang Road, Gap Road associated with early grazing leases, gold mining and Gunmark Road; or and timber harvesting. From the south, turn off the Princes Highway along Combienbar Road, 54 km east of Orbost. Wilderness wonder Drive through Club Terrace to Errinundra Road The Errinundra National Park was recently which climbs onto the Plateau. Allow two hours expanded by 12,340ha due to the State driving time from Orbost. Government’s commitment to preserving old Things to see and do growth forest for future generations. Errinundra Plateau is a south east extension of The bushwalking and management tracks are the Monaro Tablelands. It contains three granite ideal for easy and medium length walks. outcrops - Mt Ellery, Mt Morris and Cobbs Hill- • which extend into the rain clouds, causing much Mt Ellery offers spectacular views and a close park look at the granite tors. -

Volcanic Lakes and Plains of Corangamite Shire

VOLCANIC LAKES AND PLAINS OF CORANGAMITE SHIRE Destination Action Plan 2016–2019 July 2016 Acknowledgments The development of the Volcanic Lakes and Plains of Corangamite Shire Destination Action Plan has been facilitated by Great Ocean Road Tourism. The process brought together representatives from all stakeholder groups that benefit from the visitor economy; local government, state government agencies, industry and the community to develop a plan. This Plan seeks to identify the challenges and opportunities facing the Volcanic Lakes and Plains region and to establish achievable affordable priorities that if delivered would increase the Volcanic Lakes and Plains competitiveness. Facilitators Wayne Kayler Thomson and Liz Price Destination Action Plan Leadership Group We would like to thank the individuals that gave of their time, thoughts and ideas participating in the collaborative development process: Doug Pollard – Noorat Warren Ponting – Cobden Airport Karen Blomquist – Darlington – Elephant Bridge Hotel Mary McLoud – Noorat Terry Brain – Advance Camperdown Trish Wynd – Darlington Rachel Donovan– Camperdown Michael Emerson – Manager Economic Development and Peter Harkin – Councillor, Corangamite Shire Tourism, Corangamite Shire Judy Blackburn – Birches on Bourke Glenn Benson – Camperdown James Barnes – Lismore Sandy Noonan – Terang Nic Gowans – Skipton Dorothy Nicol – Lismore Eve Black – Noorat Jo Beard – Mayor, Corangamite Shire Council Chris Lang – Lismore Progress Association Anthony Meechan – Camperdown Geoff Smith – Councillor, Corangamite Shire Jo Pocklington – Derrinallum Pat Robertson – Camperdown Lesley Brown – Derrinallum Sandra Gellie – Derrinallum Chris Maguire – Camperdown/Cobden Pat Gleeson – Darlington Andrew Stubbings – Cobden PO Box 1467 Warrnambool Victoria 3280 t 03 5561 7894 e [email protected] www.greatoceanroadtourism.org.au 2 Introduction The Strategic focus of Great Ocean Road Regional Tourism Board (GORRTB) recognises that visitors to the Great Ocean Road region are primarily attracted to destinations and experiences within the region.