La Crosse Historic Landmarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of St. John Nepomucene Parish. Golden Jubilee History 1891-1941 of St

History of St. John Nepomucene Parish. Golden Jubilee History 1891-1941 of St. John's Parish, Prairie du Chien, WI., p. 5-43. CAP at Orchard Lake. Foreword IN writing this history of St. John's Congregation, every effort was made to record the important events pertaining to the origin and development of the parish as accurately as possible. In do- ing this we strove to adhere to facts and studiously avoided imputing motives and interpreting consequences. Where this may seem to have been done, it was ascertained to be factual. Since documentary records pertaining to the early history of the parish were scarce, we were forced to depend on the memory of the first members of the parish for some facts, but such information was carefully checked for accuracy. For more definite and detailed information we are indebted to the former pastors of St. John's still living, to the old files of The Courier, which were most helpful, and to the volume, "The Catholic Church in Wisconsin". A few interesting items were also gleaned from the "History of Bohemian Americans" by John Habenicht. It was naturally possible for us to give more complete and detailed information about the events that transpired during the thirteen years of our own pastorate. We hesitated at first to give comparatively so much more detailed information about our own times for fear that our motives might be misconstrued. However, our hesitancy was overcome by the thought that our task in writing this history would have been much easier had there been more information about ear- lier times available to us. -

History of St. Mary's Czestochowa Parish. Golden Jubilee St

History of St. Mary's Czestochowa Parish. Golden Jubilee St. Mary Czestochowa Catholic Church 1908-1958, Junction, Wisconsin. CAP at Orchard Lake. St. Mary Czestochowa Congregation at Junction, located one and one-half miles east of Stanley or five miles west of Thorp, Wisconsin and four miles north of Highway 29 dates back to the early 1900's for its origin, but is comparatively young as far as the history of the La Crosse Diocese is concerned. The original settlers, exclusively of Polish descent, began their residence in the Junction area around 1901. Migrating from Poland by way of Pennsylvania and Chicago and trained in hard work, they cleared the wooded and rocky area for their future homes and began the task of earning their living from the soil. The future looked bleak and difficult, but the people filled with initiative and aggressiveness of sturdy pioneers, succeeded in their endeavors with the help of God, for their land is now productive and stands as a monument to their hard labors. God and the Catholic Church always played an important role in the lives of the Polish people. Since their conversion centuries ago, they have always been faithful to the true church as the history of Poland attests to that. The settlers of Junction were no different from their forefathers. They imme- diately attached themselves to the nearest Catholic Church which happened to be located in Stanley, dedicated to the Mother of God, St. Mary's Church. By horse and on foot they went to divine services in all types of weather. -

The Catholic Bulletin

1 11 1 m "V V-->5"*.J"^; • _ TT«"~* ":, "F •'T""""T * " " """ -Y—R~^*"*"** .niiiT- iiu.I—i I ^7*^- >*r>-rrtf-r-. f'/»v THE CATHOLIC BULLETIN, MARCH 20, 1915.1 to the Ursuline Academy to complete Sir David Beatty, of the home fleet, her studies and it was while there Vice Admiral Sackville Hamilton Gar OLDEST BANK IN MI IOTA 7c^ tcHk^ that she received the gift of faith. She den, who is in command of the Franco- was baptized Christmas day, 1878, British fleet operating against the Dar and three years later joined the Order. danelles, is an Irishman. He was THE FIRST NAT'L BANK OF ST. PAUL! For thirty-four years she was a mem born at Templemore, in the County CAPITAL AND SURPLUS $5,000,000 ber of the Ursuline Community in Tipperary, in 1857. ;< OFFICERS: *m£fi Cleveland. LOUIS W. HIM,. Chairman* EVERETT H BAILBY, President. OTTO M. NELSON, Vler-PrMllcat 5??!?. ?OTl',_Ai»l«t««t CubMb Rome's New Art Gallery.—The new CYRUS I*. BROWN, VictTPrPsldcllt. ' ^'TfARTjfi'Q W MlIf'KI 1<* V raHhl** HENRY B. HOUSE, Aut. Cull« Parochial School Penny Lunch.— Pinacothica Gallery in the Vatican, EDWARD O. lUCE, Vlee-Frexldent. CHARIiES H. MUCKLKV, Canbler CHARLES E. GALL, Aut CaakiWb schools which are supported entirely opened in 1909, and to which over 150 DIRECTORS! HEW WORLD ITEMS. St. Nicholas's parochial school, Pas JAMES J. HILL, Great Northern Railway Company. ALBERT N. ROSE, Jos. Ullman. by the Indians out of their tribal saic, N. J., has joined the penny lunch works of art were brought from the LOUIS W. -

Twenty-Fifth Sunday

Twenty-FifthIn Ordinary Time Sunday THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF THE DIOCESE OF LA CROSSE September 23, 2018 LiturgySunday Masses Saturday: 4:00 pm Sunday: 7:30 am, 10:30 am, 4:30 pm Weekday Masses Monday-Friday: 6:30 am, 12:10 pm Saturday: 8:00 am Holy Day Masses Vigil Mass: 5:10 pm Holy Day: 6:30 am, 12:10 pm and 5:10 pm Holiday Masses Weekday & Saturday 8:00 am Memorial Day, July 4th, Labor Day, Thanksgiving For Holy Week, Easter & Christmas schedules call The Rectory, see bulletin or go to online website www.cathedralsjworkman.org SacramentWeekdays: 11:30-11:55 of Penance am Saturdays: 7:15-7:50 am, 3:15-3:45 pm Holy Days: 11:30-11:55 am Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament is held each First FirstFriday Friday after the 12:10 Devotions pm Mass until 2:40 pm, followed immediately by a simple benediction to conclude the 530 MAIN STREET period of adoration. LA CROSSE, WI 54601 Also see our website: 608/782-0322 www.cathedralsjworkman.org IN SYMPATHY Please pray for the eternal repose of the soul of Patricia Ann Fleming, who died recently, and for the comfort and consolation of her families and loved ones. Eternal rest grant unto Patricia, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon her. May her soul and the souls of all the faithfully departed, through the mercy of God, rest in eternal peace. Amen. FIAT - YOUNG CATHOLIC ADULT GROUP We will be starting our monthly Fiat event back up next Tuesday, September 25. -

Theocratic Governance and the Divergent Catholic Cultural Groups in the USA Charles L

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 3-19-2012 Theocratic governance and the divergent Catholic cultural groups in the USA Charles L. Muwonge Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Muwonge, Charles L., "Theocratic governance and the divergent Catholic cultural groups in the USA" (2012). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 406. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/406 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theocratic Governance and the Divergent Catholic Cultural Groups in the USA by Charles L. Muwonge Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Leadership and Counseling Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Dissertation Committee: James Barott, PhD, Chair Jaclynn Tracy, PhD Ronald Flowers, EdD John Palladino, PhD Ypsilanti, Michigan March 19, 2012 Dedication My mother Anastanzia ii Acknowledgments To all those who supported and guided me in this reflective journey: Dr. Barott, my Chair, who allowed me to learn by apprenticeship; committee members Dr. Jaclynn Tracy, Dr. Ronald Flowers, and Dr. John Palladino; Faculty, staff, and graduate assistants in the Department of Leadership and Counseling at EMU – my home away from home for the last ten years; Donna Echeverria and Norma Ross, my editors; my sponsors, the Roberts family, Horvath family, Diane Nowakowski; and Jenkins-Tracy Scholarship program as well as family members, I extend my heartfelt gratitude. -

Sacred Music Volume 122 Number 4

Santa Barbara, California SACRED MUSIC Volume 122, Number 4, Winter 1995 FROM THE EDITORS 3 Publishers A Parish Music Program CREATIVITY AND THE LITURGY 6 Kurt Poterack SURVEY OF THE HISTORY OF CAMPANOLOGY IN THE WESTERN 7 CHRISTIAN CULTURAL TRADITION Richard J. Siegel GREGORIAN CHANT, AN INSIDER'S VIEW: MUSIC OF HOLY WEEK 21 Mother M. Felicitas, O.S.B. MUSICAL MONSIGNORI OR MILORDS OF MUSIC HONORED BY THE POPE. PART II 27 Duane L.C.M. Galles REVIEWS 36 NEWS 40 EDITORIAL NOTES 41 CONTRIBUTORS 41 INDEX OF VOLUME 122 42 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of Publication: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Paul Manz, 1700 E. 56th St., Chicago, Illinois 60637 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. Schubert Treasurer Donna Welton Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Mrs. Donald G. Vellek William P. -

Father Bernard Mcgarty

Saint Mary's Parish La Crosse, by Father Bernard McGarty. Nathan Myrick opened a Trading Post at Prairie La Crosse in 1841, and shortly became Post Master of a settle ment that grew rapidly because of Federal Land Grants and Mississippi River Steam Boats. Sioux and Ho Chunk Native Americans negotiated treaties on the Prairie and played their game, which French missionaries labeled La Crosse. Twelve years later in 1853, the profile of settlers in La Crosse was: "30% born in Europe; 39 in Germany, 29 in Norway and Sweden, 23 in Britain, 19 in Ireland, 7 in Canada, 3 in France,: 70% of settlers were born in the United States; 89 in Vermont and New England, 109 in New York, 30 in Ohio, 20 in Pennsylvania, a lesser num ~ ber from Southern States:' A Wisconsin census in 1855 listed La Crosse population, 1,637. (1.) Native American numbers are ignored. If you were to walk through the village in 1853 this is what you would see: Native Americans, painted and in re galia on the streets. "1 04 Dwelling Houses, 8 Fancy and Dry Goods Stores, 4 Groceries, 2 Drugs and Medicines, 2 Boots and Shoes, 2 Hardware, 2 Tin Shops, 2 Tailor Shops, 3 Shoe Shops, 1 Harness Shop, 4 Blacksmith Shops, l Gun Shop, 2 Bakeries, l Cabinet Shop;' Also, "3 Physicians Offices, 4 Law Offices, 1 Justice Office, 5 Taverns, 1 Barber Shop, 1 Printing Office, 4 Joiners Shops, 1 Steam Saw Mill, 1 Wagon Shop, 1 Jeweler and Silver Smith's Shop, 1 Milliner Shop, 1 Office for the Sale of Government Lands, 1 Odd-Fellows Hall, 1 Court House and Jail, 3 Churches." (2.) Father Lucian Galtier was a legendary missionary from France working in the Mississippi Valley under the direc tion of the Bishop of Dubuque. -

Saskatchewan a Number Immunized

» ■. SAYS SWOPE VISCERA SAYS THAW LAWYER BELATED WINTER IS TURK-BALKAN WAR LLOYD-GEORGE'S HOME WAS TAMPERED WITH OFFERED HIM BRIBE UPON MIDDLE WEST LOSS OVER 200,000 IS WRECKEi BY BOMB Defense Springs Sensation in Superintendent Russell, of Mat- General Snow and Sleet Storm Ac. Statisticians in Casting Up Two Broken and Pres* of hatpins Trial of Dr. Hyde, teawan, Says He Rejected Severs Communication With counts Estimate This Num- ence of Women Indicate Kansas City. $20,000 Boodle. Best of the World. ber Have Perished. Suffragets Did Work. Kansas City. Mo., Fob. 24.—The bit- Albany, N. Y„ Feb. 24.—Dr. John U. Kansas Feb. 22.-—The mid- a ■ City, Mo., London, Feb, 22.—With what Is be- terest of the third trial of Russell, of the Mattea- dle west today was cut ott from com- Feb. 21.—An explosion early wrangle superintendent of the London, munication with the rest of the coun- lieved to be the heaviest fighting B. Clarke Hyde for the murder of wan state hospital for the criminal In- today partially wrecked a country try. A series of snow, sleet and rain Balkan war already recorded, Kuropean Col. Thomas H. Swope took place to- sane. testified before Governor Sulzer'ii residence In course of construction for storms prevailed, trains were delayed statisticians have been busily engaged day when attorneys for the defense committee of inquiry that he had beer chancellor of the exchequer, David and telegraph and telephone wires de- In to the loss of life and complained that they had been de offered $20,000 if he would release moralized. -

St. John'5 Parish of St

() v.. .. ..,.... tIV" '¥W" v.... v.- •.,... ¥Un ., • 1891 1941 St. John'5 Parish OF St. John Nepomucene's Parish Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin 1891 1941 COMPILED BY REVEREND PAUL J. MONARSKI The !\'lost R everend Alexander J. !\'lcGavick. D. D. Bishop of La Crosse -2 The Most Rev. Wm. R. Griffin, D. D. Auxiliary Bishop of La Crosse -3 The Present Saint John Nepomucene's Church - 4 Foreword f' writing this history of St. John's Congregation, every effort was made to record the important events per taining to the origin and development of the parish as accurately as possible. In doing this we strove to adhere to facts and studiously avoided imputing motives and in terpreting consequences. ·Where this may seem to have been done, it was ascertained to be factual. Since documentary records pertaining to the early history of the parish Were scarce, we were forced to de pend on the memory of the first members of the parish for some facts, but such information was carefully checked for accuracy. For more definite and detailed information we are indebted to the former pastors of St. John's still living, to the old files of The Courier, which were most helpful, and to the volume, "The Catholic Church in Wisconsin". A few interesting items were also gleaned from the "His tory of Bohemian Americans" by John Habenicht. It \va·s naturally possible for us to give more complete and detailed information about the events that transpired during the thirteen years of our own pastorate. We hes itated at first to give comparatively so much more detailed information about Our own times for fear that our motives , might be misconstrued. -

History of St Hedwig's Parish. the Diamont Anniversary 1891-1966 St

History of St Hedwig's Parish. The Diamont Anniversary 1891-1966 St. Hedwig's Congregation, Thorp, WI, p. 18-31. CAP at Orchard Lake. Territorial Development St. Hedwig's Congregation established in 1891 lies in the northwest section of Clark County in the Townships of Thorp, Withee, Worden and Reseburg. Before the coming of the first white settlers, little is known of the Indian history of this area. Appar- ently this territory was occupied by the Chippewa, Menomonie, Winnebago, and Dakota Indians around the middle of the 17th century. All tribal Indian claims to Clark County lands were ceded in 1837. However, individual Indian families, were still seen and lived in some parts as late as the early 1900's. The settlement and development of this area was due to its vast stretches of timber, immediately tributary to the great waterways. The two largest, the Black River flows north and south, while the Eau Claire branches in the west and flows into the Chippewa River. Originally about one-fourth of Clark County was covered with white pine and three-fourths was covered with hardwood and hemlock. This timber was sent down the Black River to La Crosse and down the Eau Claire by way of the Chippewa River to Winona and other points. The best hardwood was in the townships which are located through the middle and eastern parts of the County. Some was found in the northern portions of the towns of Worden and Reseburg. Large forests of hardwood were also found in the Towns of Thorp and Withee. -

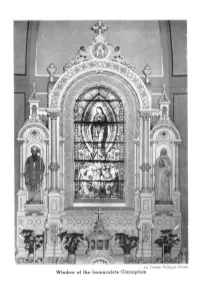

Window of the Immaculate Conception

La Crosse Tribune Photo Window of the Immaculate Conception THE Cjeniermiut <Jtisiori/ OF ST. MARY'S CHURCH 1854 1954 LA CROSSE, WISCONSIN ". We invite each and every one of you Venerable Brethren, by reason of the office you exercise, to exhort the clergy and people committed to you to celebrate the Marian Year which we proclaim to be held the whole world over from the month of December next until the same month of the coming year—just a century having elapsed since the Virgin Mother of God, amid the applause of the entire Christian people, shone with a new gem, when our predecessor of immortal memory solemnly decreed and defined that she was absolutely free from all stain of original sin. And we confidently trust that this Marian celebration may bring forth the most desired and salutary fruits which all of us long for." From the encyclical letter Fulgens Corona September 8, 1953 4 • ! k • | i % j r -'••-.. -.;•; 5? " -^ SR I • ' 1 *i ry „p*ll|||; : ; :!;; •• - ;:- l rUHb f* * ..- j "1 tft Jfe v> Hfn l K • W1H :. *H $r 5 DIOCESE OF LACROSSE 4?2 HOESCHLER BUILDING LACROSSE, WISCONSIN OFFICE OF THE BISHOP April 3, 1954 Rev. Father William L. Mooney 319 South 7th Street La Crosse, Wisconsin Dear Father Mooney: • One hundred years in the life of the Church is but one-nineteenth part of her existence. Yet this same time in the life of an American parish marks a very definite milestone in the life of Christ's Church on these shores. One cannot help going back in grateful memory to all the early pioneer priests, Sisters and people who made the noblest kind of sacrifices in order that this church might be established, and even more than that, that the children of the parish might be given their birthright, namely a Christian, American education. -

SIXTY YEARS of COMMUNITY: ST. OLAF CATHOLIC PARISH in EAU CLAIRE, WISCONSIN, 1952-2012 Michaela Walters History 489 Fall 2012 C

SIXTY YEARS OF COMMUNITY: ST. OLAF CATHOLIC PARISH IN EAU CLAIRE, WISCONSIN, 1952-2012 Michaela Walters History 489 Fall 2012 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author If society doesn't appreciate the impact of religion on the lives of people, it will sorely underestimate both what the society can do and sorely underestimate the ability of the society to achieve… If we more and more divorce ourselves from an adherence or appreciation of the impact of religion, we more and more become disinterested in terms of the impact of religion on lives, we'll quickly see ourselves in a rootlessness, if you want. Nothing pinning us down or holding us down.1 ~~Archbishop Jerome E. Listecki, former bishop of the Diocese of La Crosse 1 Joe Orso, “Q&A: Listecki Looks at Diocese Future, Past After Two Years as Bishop.” La Crosse Tribune (WI), July 14, 2007. ii Abstract This paper will explore how the parish community of St. Olaf in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, established in 1952, reflects the Roman Catholic Church, specifically at the local, state, and national levels in the United States. It will also discuss the various changes that have occurred in the past 60 years of its history in terms of the various locations of worship for the members, the growth of the community outreach programs, and the effects of the Second Vatican Council. This ecumenical council was a meeting of Catholic bishops from around the whole that brought reform to the Catholic Church and affected the relationship of the Catholic Church to the world.