Climate Change Adaptation Plan for the Northern Adelaide Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edition #38 • WINTER 2012 Salisbury's Strongest Take on Hawaii

Edition #38 • WINTER 2012 Salisbury’s Strongest Take on Hawaii. Read about Gavin Nugent and Brad Wauer who will push their bodies to the extreme in the Ironman World Championships. www.salisbury.sa.gov.au facebook.com/cityofsalisbury twitter.com/cityofsalisbury FOOD & HOSPITALITY METALS & ENGINEERING HAIR & BEAUTY AUTOMOTIVE BUILDING & CONSTRUCTION ELECTROTECHNOLOGY Your trade career ... starts here. TRADE TRAINING IS NOT JUST PART OF WHAT WE DO- IT’S ALL THAT WE DO! St Patrick’s Technical College combines a unique trade focused SACE with award winning trade and apprenticeship training for Year 11 & 12 students. Come and see why three out of every four students leaves St Patrick’s in an apprenticeship. COLLEGE TOURS every Thursday @ 9.30am OPEN DAY Sun 26 August PLACES LIMITED - ENROL TODAY TO START YOUR TRADE CAREER AT YEAR 11 IN 2013. Visit www.stpatstech.sa.edu.au or phone 1300 765 384 for details. Contents From the y We arem more thana half wayor through 2012 and for Features Salisbury things are well underway to encourage growth and economic prosperity as we work on the development and refurbishment of various sites across the city. Salisbury town centre revitalisation continues to be a priority for Council, with community consultation helping us to ensure we get it right for residents, businesses and visitors. Lake Windemere will undergo a transformation with the demolition of the Salisbury North Community Centre scheduled and plans for a new housing development at Walpole Road. Read more about these projects on 06 the Council Report pages inside. Salisbury’s Strongest Take on Elsewhere, two of Salisbury’s Ironmen will be competing in the Hawaii Ironman Championships and are a Hawaii Ironman Championship testament to the great sporting facilities available in the city. -

Edition-61-Salisbury-Aware-Autumn-2020.Pdf

SALISBURY AWARE FREE | edition 61 | autumn 2020 SALISBURY CATCHES FRINGE FEVER INNOVATION MEETS CARVING NEW SKILLS CELEBRATING HISTORY AT THE HUB AND FRIENDSHIPS OUR YOUTH City of Salisbury | PO Box 8 Salisbury SA 5108 | Phone 8406 8222 | TTY 8406 8596 | [email protected] salisbury.sa.gov.au @cityofsalisbury @cityofsalisbury @cityofsalisbury A MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR The year is well and truly The multi-faceted abilities of the Plaza and off to a flying start with a Salisbury Community Hub space have also number of exciting events been put on show via our array of new digital programs and school holiday activities. and programs being held within the City of Salisbury Whenever I walk through the Hub, it is across the first quarter of fabulous to see the community embracing the year. the building in the way it was intended. We kicked off 2020 with the Australia Day At any given time it boasts the bustling celebrations in the Salisbury Civic Plaza/ and active environment Council intended Inparrinthi Kumangka, which offered a – whether that involves a pair of children valuable opportunity to celebrate some of our playing a game of chess, a student charging high-achieving residents while welcoming in their laptop on the bleachers, friends sharing dozens of new Australian citizens. lunch on the outdoor terrace or residents making use of the many meeting rooms and Another flagship event, Salisbury Secret quiet spaces perched along the ground and Garden, also brought members of our first floors. community from all walks of life to the Plaza for a weekend of music, entertainment and I am excited at the prospect of what is yet to Mayor Gillian Aldridge OAM relaxation. -

Adelaide Plains Council Strategic Plan 2020-2024

Adelaide Plains Council Strategic Plan 2020-2024 Proprietary Information Statement The information contained in this document produced by Holmes Dyer Pty Ltd is solely for the use of the Client identified on the coversheet for the purpose for which it has been prepared and Holmes Dyer Pty Ltd takes no responsibility to any third party who may rely upon this document. Document Control Revision Description Author Date v6 Draft for public notice CWS BC 12.11.2020 v7 Draft for public notice PCWS BC 19.11.2020 v8 Draft for public notice AFB BC 24.11.2020 v9 Draft for public notice FFB BC 24.11.2020 Final For Adoption BC 13.01.2021 ii 01_ Foreward Page 1 02_ Our Shared Vision Page 5 03_ Our Shared Context Page 9 04_ Our Shared Approach Page 21 05_ Review and Monitor Page 33 1 01 FOREWARD A message from the Mayor As newly elected representatives of the Adelaide Plains Community we come together at a time of significant opportunities and challenges for the Council. These opportunities and challenges will frame our approach and shape our priorities for Adelaide Plains to 2024. Our Community Our Environments We are beginning to experience population growth which could We are fortunate to be custodians of a globally significant and peak at over 300 new people joining our community each year - intact remnant coastal habitat that has the dual economic long into the future. Growth can put pressure on infrastructure function of providing a major natural tourism asset and a nursery and generate demand for services and facilities that exceeds function supporting the sustainability of commercial fisheries. -

MINUTES of the MEETING of the BAROSSA COUNCIL Held on Tuesday 21 April 2020 Commencing at 9.00Am in the Council Chambers, 43-51 Tanunda Road, Nuriootpa

2020/196 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BAROSSA COUNCIL held on Tuesday 21 April 2020 commencing at 9.00am in the Council Chambers, 43-51 Tanunda Road, Nuriootpa 1.1 WELCOME Mayor Bim Lange declared the meeting open at 9.00am. 1.2 MEMBERS PRESENT Mayor Bim Lange, Crs Leonie Boothby, John Angas, Crs Tony Hurn, David Haebich, Dave de Vries, Russell Johnstone, Don Barrett, Cathy Troup and Carla Wiese-Smith 1.3 LEAVE OF ABSENCE Nil 1.4 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Nil 1.5 MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETINGS – FOR CONFIRMATION MOVED Cr de Vries that the Minutes of the Council meeting held on Tuesday 17 March 2020 and Special Council meeting held Thursday 26 March 2020 at 6.30pm, as circulated, be confirmed as a true and correct record of the proceedings of that meeting. Seconded Cr Haebich CARRIED 2018-22/93 1.6 MATTERS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MINUTES Nil 1.7 PETITIONS Nil 1.8 DEPUTATIONS Nil MOVED Cr Wiese-Smith that the matter relating to Council meeting of 21 April 2020 agenda item 1.10 Question on Notice – Councillor Angas – Impact of Nil Rate Increase for 2020-21 be brought forward for discussion immediately. Seconded Cr de Vries CARRIED 2018-22/94 The Barossa Council 20/21117 Minutes of Council Meeting held on Tuesday 21 April 2020 2020/197 1.10 QUESTION ON NOTICE – COUNCILLOR ANGAS – IMPACT OF NIL RATE INCREASE FOR 2020-21 B10322 MOVED Cr de Vries that Council receive and note the response and that the question and response be placed in the minutes. -

Annual Report Lgfa

2 013 ANNUAL REPORT LGFA Your Local Government Finance Authority of South Australia Member Councils as at June 30 2013 Adelaide City Council District Council of Karoonda East Murray City of Port Lincoln Adelaide Hills Council District Council of Kimba Port Pirie Regional Council Alexandrina Council Kingston District Council City of Prospect The Barossa Council Light Regional Council Renmark Paringa Council District Council of Barunga West District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula District Council of Robe Berri Barmera Council District Council of Loxton Waikerie Municipal Council of Roxby Downs City of Burnside District Council of Mallala City of Salisbury Campbelltown City Council Corporation of the City of Marion Southern Mallee District Council District Council of Ceduna Mid Murray Council District Council of Streaky Bay City of Charles Sturt City of Mitcham Tatiara District Council Clare and Gilbert Valleys Council District Council of Mount Barker City of Tea Tree Gully District Council of Cleve City of Mount Gambier District Council of Tumby Bay District Council of Coober Pedy District Council of Mount Remarkable Corporation of the City of Unley Coorong District Council Rural City of Murray Bridge City of Victor Harbor District Council of Copper Coast Naracoorte Lucindale Council Wakefield Regional Council District Council of Elliston Northern Areas Council Corporation of the Town of Walkerville The Flinders Ranges Council City of Norwood, Payneham and St. Peters Wattle Range Council District Council of Franklin Harbour City of Onkaparinga -

Annual Report 2018 - 2019 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 - 2019 www.gawler.sa.gov.au CONTENTS Statement of Commitment to Aboriginal Australians ....................................................................3 MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR .........................................................................................................4 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO ..............................................................................................................5 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA ............................................................................................................6 YOUR COUNCIL .................................................................................................................................7 Council Member Allowances 2018/2019 ......................................................................................8 Council Member Training and Development ................................................................................8 Elector Representation .................................................................................................................8 Public Participation at Meetings ...................................................................................................8 Decision Making ...........................................................................................................................9 Committee Structures .................................................................................................................10 Other Council Committees ....................................................................................................11 -

Community Engagement Policies in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America Appendix C July, 2012

Report for the City of Guelph: Community Engagement Policies in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America Appendix C July, 2012 Kim Chuong, Kathryn Walton, and Morgan Marini The Research Shop, University of Guelph APPENDIX C Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia Melbourne, Victoria ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Engagement Framework ......................................................................................................................... 7 State of Victoria policy ............................................................................................................................ 8 Onkaparinga, South Australia ....................................................................................................................... 13 Engagement Framework ........................................................................................................................ 13 Engagement Handbook ......................................................................................................................... 15 State of South Australia ................................................................................................................................ 22 Community Engagement Handbook: Model Framework for Leading Practice in Local -

Publication2

Way2Go e-newsletter issue 1 : term 1 : 2012 Welcome to Way2Go 2012 Date to remember Our School and Education Programs Team is looking forward to working with current and Ride2School Day will be held on new Way2Go schools in 2012 and beyond. Our Way2Go partnership is with local govern- 23 March 2012. To find out more ments and schools. Below are the names and contact details of our Education Consultants and/or register your school for this event go to and the local government areas each will be working with in 2012. These include councils www.bikesa.asn.au/ and schools new to the program, as well as schools that are already actioning their School RiderInfo_Programs_ Travel Plans. Please feel welcome to contact us for advice, support or to share a good news NatRideSchoolDay story. Sue McMillan Dan Crane Krystil Ellis Coordinator School and Education Education Consultant Education Consultant Programs [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] phone: 84021917 phone: 8343 2088 phone: 8343 2459 mobile: 0400661119 mobile: 0401 120 864 mobile: 0421 832 818 Adelaide Hills Council City of Charles Sturt Alexandrina Council Berri Barmera Council City of Holdfast Bay City of Port Adelaide Enfield City of Burnside City of Marion City of Whyalla City of Campbelltown City of Onkaparinga DC Victor Harbor City of Mount Gambier City of Playford DC Yankalilla City of Mitcham City of Port Lincoln Iwantja (Indulkana) City of Payneham Norwood St Peters City of West Torrens Port Augusta City Council City of Prospect DC Streaky Bay Port Pirie DC City of Salisbury MC Roxby Downs City of Tea Tree Gully RC Murray Bridge City of Unley The Barossa Council DC Grant Town of Gawler DC Loxton Waikerie DC Mount Barker Way2Go Bike Ed DC Robe Town of Walkerville 2 Way2Go e-newsletter issue 1 : term 1 : 2012 Annual Review two we will invite several new Way2Go schools and button) crossings; school An important part of having groups of teachers, country those schools that zones and crossing monitors. -

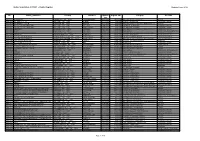

Native Vegetation Clearance Application Register

Native Vegetation Act 1991 - Public Register Updated June 2010 File Owner_Surnames Locality Hundred Applicn Registd date Category Decision date 2001/2113 MATTSSON COFFIN BAY, SA, 5607 LAKE WANGARY 30/08/2001 25/06/2004 Miscellaneous Developments Exempt 2003/2069 BLEXAN PTY LTD ADELAIDE, SA, 5000 HYNAM 26/11/2002 3/09/2003 Irrigation - Horticulture Conditional Consent 2003/2070 WR BAILEY PTY LTD FRANCES, SA, 5262 BINNUM 21/08/2003 9/09/2003 Miscellaneous Developments - Scattered trees Refused 2003/2071 SA WATER CORPORATION ADELAIDE, SA, 5001 ADELAIDE 4/09/2003 9/09/2003 Not Specified / Unknown Conditional Consent 2003/2071 SA WATER CORPORATION ADELAIDE, SA, 5001 NOARLUNGA 4/09/2003 9/09/2003 Not Specified / Unknown Conditional Consent 2003/2072 NEUMANN MUNDULLA, SA, 5270 WIRREGA 22/08/2003 10/09/2003 Miscellaneous Developments - Scattered trees Conditional Consent 2003/2073 MEAD LAMEROO, SA, 5302 COTTON 3/09/2003 10/09/2003 Brush cutting Partial Consent (Conditional) 2003/2074 KANGAROO ISLAND COUNCIL KINGSCOTE, SA, 5223 MENZIES 21/08/2003 10/09/2003 Miscellaneous Developments - Access Tracks Conditional Consent 2003/2075 THOMSON NARACOORTE, SA, 5271 GLEN ROY 22/08/2003 10/09/2003 Irrigation - Unknown Use Conditional Consent 2003/2076 CITY OF ONKAPARINGA NOARLUNGA CENTRE, SA, 5168 NOARLUNGA 28/03/2003 10/09/2003 Grazing - Increased Intensity Cancelled (by admin) 2003/2077 CITY OF ONKAPARINGA NOARLUNGA CENTRE, SA, 5168 NOARLUNGA 3/04/2003 10/09/2003 Miscellaneous Developments - Access Tracks Cancelled (by admin) 2003/2078 CITY OF TEA TREE -

CITY of PLAYFORD Cycling and Walking STRATEGY FINAL | FEBRUARY 2014

CITY OF PLAYFORD CYCLING AND WALKING STRATEGY FINAL | FEBRUARY 2014 1 CITY OF PLAYFORD CYCLING AND WALKING STRATEGY urban design landscape architecture urban planning ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Cycling and Walking Strategy was commissioned by the City of Playford (CoP) under the direction of the Project Steering Group: – Richard Tang, Traffic Engineer (CoP) – Lisa Atwell, OPAL Manager (CoP) – Ken Potter, Transport Planner (CoP) – R ob Veitch, Manager Growth and Regeneration (CoP) – Greg Salmon, Urban Planner (CoP) – Edith Mayer, Manager Community Development and Stakeholder Engagement (Renewal SA) – Tim McEvoy, Senior Planner (DPTI) The Oxigen team preparing the report was Luke Stein, James Hayter and Christina Fusco. ISSUE: FINAL _ 21.02.14 cover IMAGE: CourtesY OF OPAL, SA HEALTH 2 CONTENTS CITY OF PLAYFORD CONTENTS I 4 ntroduction 8 Part 1: Benefits 14 Part 2: Vision 18 Part 3: Existing Conditions 48 Part 4: Consultation 54 Part 5: Best Practice 68 Part 6: Recommendations 106 Part 7: Implementation 3 CITY OF PLAYFORD CYCLING AND WALKING STRATEGY OVERVIEW Cycling and walking are fundamental everyday modes of transport and central to active living and supporting healthy lifestyles. Despite this, many of our urban environments are not conducive to walking or cycling. Getting around the City of Playford on foot or bike can be a challenge. Like many parts of Australia, the City of Playford has been planned and designed predominantly for motor vehicle transport. The car-dominant environment and focus on infrastructure and budgets supporting this mode of transport makes the simple task of getting from place to place difficult for those who do not have a car, or who wish to travel by other modes. -

Project/Work Groups 2018-19 As at 31/12/2018

Project/Work Groups 2018-19 as at 31/12/2018 Asset Management Alex Brown, Adelaide City Council [email protected] Asset Management Alex Oulianoff, Mount Barker District [email protected] Council Asset Management Annette Martin (Deputy Chairperson), [email protected] City of Charles Sturt Asset Management Anthony Amato, Town of Gawler [email protected] Asset Management Cadel Blunt, City of Holdfast Bay [email protected] Asset Management Chris Birch, City of Prospect [email protected] Asset Management David Edgerton, APV Valuers & Asset [email protected] Management Asset Management Donna Stubbs, City of Charles Sturt [email protected] Asset Management Elizabeth Waters, The Barossa Council [email protected] Asset Management Emil Bogatec, City of Onkaparinga [email protected] Asset Management Gary Lewis, District Council of Yankalilla [email protected] Asset Management Gary Long, City of Prospect [email protected] Asset Management Gideon Joubert, Alexandrina Council [email protected] u Asset Management Grace Pelle, City of Playford [email protected] Asset Management Joe Scordo, Light Regional Council [email protected] Asset Management Jonathan Crook, City of Tea Tree Gully [email protected] Asset Management Kate George, City of Salisbury [email protected] Asset Management Katy Bone (Chairperson), Town of [email protected] Walkerville Asset Management Leta -

Edition-60-Salisbury-Aware-Summer-2019.Pdf

SALISBURY AWARE FREE | edition 60 | summer 2019 CELEBRATING THE SALISBURY COMMUNITY HUB MAKING STRIDES AT ART TRANSFORMS GROWING FOR GOLD BRIDGESTONE RESERVE LOCAL SPACES MARKS MILESTONE City of Salisbury | PO Box 8 Salisbury SA 5108 | Phone 8406 8222 | TTY 8406 8596 | [email protected] salisbury.sa.gov.au @cityofsalisbury @cityofsalisbury @cityofsalisbury A MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR The official opening of the Salisbury Breakfast and Salisbury Secret Garden. Keep Community Hub will take place over the an ear out for the upcoming announcement of weekend of 30 November and 1 December. our Secret Garden headline act! Save the dates in your calendar as there is something planned for everyone, This edition of Salisbury Aware touches including a food market, children’s activities, on some of the highlights on offer for our entertainment on the large outdoor screen community. Recently, school-aged children and the annual Christmas Parade. We look had the chance to try their hand at a variety forward to exploring the new Hub with you of sports as part of the 20th annual Growing and discovering the huge potential of its for Gold program. flexible spaces for all of our community from the young to seniors. The Para Hills Community Hub’s ukulele group is always open to members – as are a range Excitingly, work is underway to develop the of other groups and activities from bingo to Bridgestone Athletics Centre at Bridgestone table tennis. Reserve in Salisbury. The centre will include a 400 metre elite level athletics track to be If you’re still unsure on what services the available for all participants from local clubs Salisbury Community Hub will offer, these Mayor Gillian Aldridge OAM to Olympic training.