The Strengths of Our Methodological Divides: Five Navigators, Their Struggles and Successes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

Rhetoric and Media Studies 1

Rhetoric and Media Studies 1 cocurricular activity; credit is available to qualified students through the RHETORIC AND MEDIA practicum program. STUDIES Facilities Radio. Located in Templeton Campus Center, KLC Radio includes two fully Chair: Mitch Reyes equipped stereo studios, a newsroom, and offices. The station webcasts Administrative Coordinator: TBD on and off-campus. From its humanistic roots in ancient Greece to current investigations of the impact of digital technology, rhetoric and media studies is both one of Video. Lewis & Clark’s video production facility includes digital editing the oldest and one of the newest disciplines. Our department addresses capabilities, computer graphics, portable cameras and recording contemporary concerns about how we use messages (both verbal and equipment, and a multiple-camera production studio. Additional video visual) to construct meaning and coordinate action in various domains, recording systems are available on campus. including the processes of persuasion in politics and civic life, the effects of media on beliefs and behavior, the power of film and image to frame The Major Program reality, and the development of identities and relationships in everyday The major in rhetoric and media studies combines core requirements life. While these processes touch us daily and are part of every human with the flexibility of electives. Required courses involve an introductory interaction, no other discipline takes messages and their consequences overview to the field, a course on the design of media or interpersonal as its unique focus. messages, core courses on the theories and methods of rhetoric and media studies, and satisfactory completion of a capstone course. The Department of Rhetoric and Media Studies offers a challenging and Elective courses enable students to explore theory and practice in a wide integrated study of theory and practice. -

Four-Year Pathway Plan

FOUR-YEAR PATHWAY PLAN North Carolina Community College to Chowan University A.A. or A.S. to B.A. or B.S. Mass Communication, Communication Studies, B.A. NCCCS FIRST YEAR CU THIRD YEAR Fall Semester SHC Fall Semester SHC ACA 122 – College Transfer Success 1 LS 201 – LitSphere 1 ENG 111 – Writing & Inquiry 3 REL 101 – Understanding the Bible 3 Social/Behavioral Sciences (Any) 3 Global Learning Core 3 CIS 110 – Introduction to Computers 3 COMM 135 – Media Writing 3 Elective 3 COMM 225 – Digital and Online Media 3 Elective 3 Communication Studies Concentration* 3 Total SHC 16 Total SHC 16 Spring Semester SHC Spring Semester SHC ENG 112 – Writing/Research in the Disciplines 3 LS 202 – LitSphere 1 Communications/Humanities/Fine Arts (Any) 3 Global Learning Core 3 Social/Behavioral Sciences (Any) 3 COMM 230 – Mass Media and Society 3 COMM 231 – Public Speaking 3 COMM 335 – Grammar for Media COMM 110 – Introduction to Communication 3 Professionals 3 Communication Studies Concentration* 3 Elective 1 Total SHC 15 Total SHC 14 NCCCS SECOND YEAR CU FOURTH YEAR Fall Semester SHC Fall Semester SHC Communications/Humanities/Fine Arts (Any) 3 Global Learning Core 3 Social/Behavioral Sciences (Any) 3 COMM 340 – Research Methods in Mass Natural Sciences (Any) 4 Communication 3 Elective 3 COMM 435 – Theories of Mass Elective 3 Communication 3 Communication Studies Concentration* 3 Communication Studies Elective** 3 Total SHC 16 Total SHC 15 Spring Semester SHC Spring Semester SHC Math (Any) 3‐4 Global Learning Core 3 Communications/Humanities/Fine Arts -

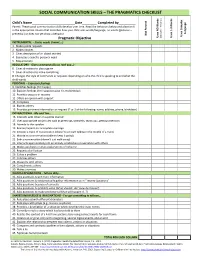

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

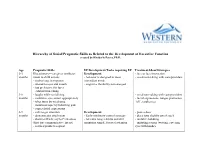

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

A Communication Aid Which Models Conversational Patterns

A communication aid which models conversational patterns. Norman Alm, Alan F. Newell & John L. Arnott. Published in: Proc. of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ‘87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. A communication aid which models conversational patterns Norman ALM*, Alan F. NEWELL and John L. ARNOTT University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, U.K. The research reported here was published in: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ’87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. The RESNA (Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America) site is at: http://www.resna.org/ Abstract: We have developed a prototype communication system that helps non-speakers to perform communication acts competently, rather than concentrating on improving the production efficiency for specific letters, words or phrases. The system, called CHAT, is based on patterns which are found in normal unconstrained dialogue. It contains information about the present conversational move, the next likely move, the person being addressed, and the mood of the interaction. The system can move automatically through a dialogue, or can offer the user a selection of conversational moves on the basis of single keystrokes. The increased communication speed which is thus offered can significantly improve both the flow of the conversation and the disabled person’s control of the dialogue. * Corresponding author: Dr. N. Alm, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, UK. A communication aid which models conversational patterns INTRODUCTION The slow rate of communication of people using communication aids is a crucial problem. -

The Mass Media, Democracy and the Public Sphere

Sonia Livingstone and Peter Lunt The mass media, democracy and the public sphere Book section Original citation: Originally published in Livingstone, Sonia and Lunt, Peter, (eds.) Talk on television audience participation and public debate. London : Routledge, UK, 1994, pp. 9-35. © 1994 Sonia Livingstone and Peter Lunt This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/48964/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2013 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Original citation: Livingstone, S., and Lunt, P. (1994) The mass media, democracy and the public sphere. In Talk on Television: Audience participation and public debate (9-35). London: Routledge. Chapter 2 The mass media, democracy and the public sphere INTRODUCTION In this chapter we explore the role played by the mass media in political participation, in particular in the relationship between the laity and established power. -

Semiotics of Political Communication Special Issue of Punctum

CALL FOR PAPERS Semiotics of political communication Special issue of Punctum. International Journal of Semiotics EDITOR: Gregory Paschalidis TIMELINE: In the last few decades the field of political communication is characterized by an increasing degree of pluralization and fluidity. The large-scale crisis Deadline of long-established political agents (e.g. traditional political parties, the for Abstracts: April 20, 2020 European Union) has proceeded together with the rise of a wide array of new parties, NGOs and social movements. The media ecosystem, on the Notice other hand, marked by the hybrid interplay of legacy and digital media, of Acceptance has become distinctively polycentric, multi-voiced and participative. of the Abstract: April 30, 2020 Political identities and communities, finally, have become notably more fluid and inconstant, signaling major shifts in the terms and forms of politi- Deadline cal representation. The basic premise of our invitation to investigate the for Submission of changing semiotic nature of contemporary politics is Pertti Ahonen’s asser- Full Papers: tion that “politics is always a communicative enterprise”, inherently August 31, 2020 embedded in narration, symbolism, representation and signification. Having in mind a comprehensive understanding of political agency Peer Review (including national and supra-national entities, political parties and NGOs, Due: October 19,, 2020 social movements and activist organizations) and with a specific historical focus on the post-Cold War period, we invite contributions (case studies or Final Revised theoretical articles) that address the semiotic labor involved in contempo- Papers Due: rary political communication by investigating verbal and/or non-verbal November 30, 2020 political discourse across all the different communication modes, media and practices. -

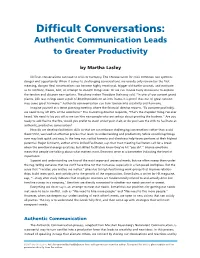

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity by Martha Lasley Difficult conversations can lead to crisis or harmony. The Chinese word for crisis combines two symbols: danger and opportunity. When it comes to challenging conversations, we usually only remember the first meaning, danger. Real conversations can become highly emotional, trigger old battle wounds, and motivate us to confront, freeze, bolt, or attempt to smooth things over. Or we can choose lively discussions to explore the tension and discover new options. The piano maker Theodore Steinway said, “In one of our concert grand pianos, 243 taut strings exert a pull of 40,000 pounds on an iron frame. It is proof that out of great tension may come great harmony.” Authentic communication can turn tension into creativity and harmony. Imagine yourself at a tense planning meeting where the financial director reports, “To compete profitably, we need to lay off 20% of the workforce.” The marketing director responds, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. We need to lay you off so we can hire new people who are serious about growing the business.” Are you ready to add fuel to the fire, would you prefer to crawl under your chair, or do you have the skills to facilitate an authentic, productive conversation? How do we develop facilitation skills so that we can embrace challenging conversations rather than avoid them? First, we need an effective process that leads to understanding and productivity. While smoothing things over may look quick and easy, in the long run, radical honesty and directness help teams perform at their highest potential. -

Towards a Practical Communication Intervention

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Mathematics and Statistics Faculty and Staff Publications Academic Department Resources 2014 Towards a Practical Communication Intervention Florentin Smarandache Stefan Vladutescu Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/math_fsp Part of the International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons, Mathematics Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Revista de cercetare [i interven]ie social\, 2014, vol. 46, pp. 243-254 The online version of this article can be found at: Working together www.rcis.ro, www.doaj.org and www.scopus.com www.rcis.ro Towards a Practical Communication Intervention Florentin SMARANDACHE1, {tefan VL|DU}ESCU2 Abstract The study starts from evidence that several communication acts fail, but nobody is called to intervene and nobody thinks of intervening. Examining diffe- rent branches (specialties) of the communication discipline and focusing on four possible practices, by comparison, differentiation, collating and corroboration, the current study brings arguments for a branch of the communication discipline that has as unique practical aim the communicational intervention, the practical, direct and strict application of communication research. Communication, as disci- pline, must create an instrument of intervention. The discipline which studies communication globally (General Communication Science) has developed a strong component of theoretical and practical research of communication phenomena (Applied Communication Research), and within a niche theory (Grounded Prac- tical Theory – Robert T. Craig & Karen Tracy, 1995) took incidentally into account the direct, practical application of communication research. We propose Practical Communication Intervention, as speciality of communication as an academic discipline. Practical Communication Intervention must be a field specialty in the universe of communication. -

How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T

20042004 ICA ICAPresidential Presidential Address Address How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T. Craig This article is a revision of the author’s presidential address to the 54th annual conference of the International Communication Association, presented May 29, 2004, in New Orleans, Louisiana. Using recent public discourse on talk and drugs as an example, it reflects on our culture’s preoccupation with communication and the pervasiveness of metadiscourse (talk about talk for practical purposes) in pri- vate, public, and academic discourses. It argues that communication theory can be used to describe and analyze the common vocabularies of public metadiscourse, critique assumptions about communication embedded in those vocabularies, and contribute useful new ways of talking about talk in the public interest. “Talk to your kids.” “Talk to your kids about drugs.” “Talk to your doctor.” “Talk to your doctor about Ambien.” “Ask you doctor if Lipitor is right for you.” “Ask your doctor if Advair is right for you.” “Talk. Know. Ask.” “Questions: The antidrug.” This collage of quotations selected from recent drug company commercials and antidrug public service announcements highlights a well-known irony in the pub- lic discourse on drugs that is not, however, my main point. Yes, the culture that produced these ads is rather obsessed with drugs. That culture is also rather obsessed with talk or, more generally, with communication. Both obsessions are on display in these ads in interesting juxtaposition. Drugs, in this cultural logic, are powerful and therefore as dangerous as they are desirable. They solve problems and they cause problems. -

Communication Theory and the Disciplines JEFFERSON D

Communication Theory and the Disciplines JEFFERSON D. POOLEY Muhlenberg College, USA Communication theory, like the communication discipline itself, has a long history but a short past. “Communication” as an organized, self-conscious discipline dates to the 1950s in its earliest, US-based incarnation (though cognate fields like the German Zeitungswissenschaft (newspaper science) began decades earlier). The US field’s first readers and textbooks make frequent and weighty reference to “communication theory”—intellectual putty for a would-be discipline that was, at the time, a collage of media-related work from the existing social sciences. Soon the “communication theory” phrase was claimed by US speech and rhetoric scholars too, who in the 1960s started using the same disciplinary label (“communication”) as the social scientists across campus. “Communication theory” was already, in the organized field’s infancy, an unruly subject. By the time Wilbur Schramm (1954) mapped out the theory domain of the new dis- cipline he was trying to forge, however, other traditions had long grappled with the same fundamental questions—notably the entwined, millennia-old “fields” of philos- ophy, religion, and rhetoric (Peters, 1999). Even if mid-century US communication scholars imagined themselves as breaking with the past—and even if “communica- tion theory” is an anachronistic label for, say, Plato’s Phaedrus—no account of thinking about communication could honor the postwar discipline’s borders. Even those half- forgotten fields dismembered in the Western university’s late 19th-century discipline- building project (Philology, for example, or Political Economy)haddevelopedtheir own bodies of thought on the key communication questions. The same is true for the mainline disciplines—the ones we take as unquestionably legitimate,thoughmostwereformedjustafewdecadesbeforeSchramm’smarch through US journalism schools.