Football at Penn State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Conversation Summer 2019 - Volume 32, No

Conservation Conversation Summer 2019 - Volume 32, No. 2 2019 Centre County Envirothon The Centre County Conservation District sponsored the 35th annual Centre County Envirothon on May 8, 2019 at Bald Eagle State Park. Ten teams from Central PA Institute of Science and Technology, Penns Valley Area, Bald Eagle Area, Bellefonte and State College Area high schools partici- Inside this issue: pated on a beautiful spring day. The Envirothon tests students’ knowledge Page of five subject areas: Aquatic Ecology; Forestry; Soils and Land Use; Wild- 1 Envirothon Event life; and Agriculture & the Environment: Knowledge & Technology to Feed the World, the current environmental issue topic for 2019. 2-3 DEP Open House— Streams in Your For the first time in 20 years, a team from State College Area high school Community captured the County Envirothon title. The State College “Animal Crackers” team scored 397 out of a possible 500 points. Team members Willow 4-5 Chesapeake Bay Martin, Adalee Wasikonis, Caroline Vancura, Luly Kaye and Katy Liu also Program achieved the highest scores at the Current Issue, Forestry, and Soils and Land Use stations. The Bald Eagle Area I team placed second with a score 6-7 DG&LVR Program of 391 and also achieved the highest scores at the Wildlife station. The Penns Valley Area I team placed third with a score of 370 and achieved the 8-9 AG BMP Grants highest score at the Aquatic Ecology station. Susan Braun is the State College Envirothon team advisor. 10 Watershed News 11 Poster Contest 12 Contact Info./Calendar The State College team represent- ed Centre County at the Pennsyl- vania Envirothon on May 21 and 22 at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown and Windber Recre- ation Park. -

2021 Keystone Media Awards

2021 Professional Keystone Media Awards DIII ‐ Multi‐day publications ‐ 10,000 to 19,999 circulation Category Name Award Organization Credits Entry Title York Daily Record/Sunday Rock stars returned to build a better York Investigative Reporting First Place News Dylan Segelbaum, Neil Strebig but left promises unfulfilled Official: I was targeted and Tax collector Investigative Reporting Second Place The York Dispatch Lindsey O'Laughlin banished to sewer complex Honorable Investigative Reporting Mention Hazleton Standard‐Speaker Jill Whalen Doggie dilemma The Tribune‐Democrat, Dave Sutor, Thomas Slusser, Caroline Enterprise Reporting First Place Johnstown Feightner Iwo Jima 75th Anniversary Lehigh Valley Media Group/The Express‐ Enterprise Reporting Second Place Times,Easton Staff Swing County, Swing State Honorable The Tribune‐Democrat, Enterprise Reporting Mention Johnstown Dave Sutor, Russ O'Reilly Socialism Unpacked Whoever wins Northampton County will probably win the presidency; On the verge of electoral power (Parts 1 & 2); We scoured a Pa. swing county's voting Lehigh Valley Media records; How Joe Biden won Northampton Group/The Express‐ County; Voters fight to have their ballots News Beat Reporting First Place Times,Easton Sara K. Satullo counted Restaurant industry fights for survival in News Beat Reporting Second Place Pocono Record Brian Myszkowski the Poconos We aren't as spooked: How the Amish are responding to the coronavirus; What does it mean to be homeless in Pennsylvania during coronavirus pandemic?; How will Pa. distribute -

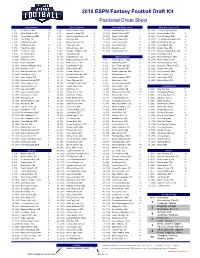

2010 Html Master File

2010 ESPN Fantasy Football Draft Kit Positional Cheat Sheet Quarterbacks Running Backs Running Backs (ctn'd) Wide Receivers (ctn'd) 1. (9) Drew Brees, NO 10 1. (1) Chris Johnson, TEN 9 73. (214) Jonathan Dwyer, PIT 5 63. (195) Jerricho Cotchery, NYJ 7 2. (13) Aaron Rodgers, GB 10 2. (2) Adrian Peterson, MIN 4 74. (216) Maurice Morris, DET 7 64. (200) Chris Chambers, KC 4 3. (21) Peyton Manning, IND 7 3. (3) Maurice Jones-Drew, JAC 9 75. (219) Albert Young, MIN 4 65. (201) Chaz Schilens, OAK 10 4. (23) Tom Brady, NE 5 4. (4) Ray Rice, BAL 8 76. (225) Danny Ware, NYG 8 66. (202) T.J. Houshmandzadeh, BAL 8 5. (39) Matt Schaub, HOU 7 5. (5) Steven Jackson, STL 9 77. (227) Julius Jones, SEA 5 67. (204) Dexter McCluster, KC 4 6. (40) Philip Rivers, SD 10 6. (6) Frank Gore, SF 9 78. (228) Lex Hilliard, MIA 5 68. (209) Lance Moore, NO 10 7. (45) Tony Romo, DAL 4 7. (8) Michael Turner, ATL 8 79. (231) Deji Karim, JAC 9 69. (210) Golden Tate, SEA 5 8. (67) Brett Favre, MIN 4 8. (11) DeAngelo Williams, CAR 6 80. (238) Isaac Redman, PIT 5 70. (220) Darrius Heyward-Bey, OAK 10 9. (77) Joe Flacco, BAL 8 9. (14) Ryan Grant, GB 10 71. (223) Deon Butler, SEA 5 10. (87) Jay Cutler, CHI 8 10. (16) Cedric Benson, CIN 6 Wide Receivers 72. (224) Nate Washington, TEN 9 11. (93) Eli Manning, NYG 8 11. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Penalties for Hospital Acquired Conditions

Penalties For Hospital Acquired Infections Kaiser Health News Penalties For Hospital Acquired Conditions Medicare is penalizing hospitals with high rates of potentially avoidable mistakes that can harm patients, known as "hospital-acquired conditions." Penalized hospitals will have their Medicare payments reduced by 1 percent over the fiscal year that runs from October 2014 through September 2015. To determine penalties, Medicare ranked hospitals on a score of 1 to 10, with 10 being the worst, for three types of HACs. One is central-line associated bloodstream infections, or CLABSIs. The second if catheter- associated urinary tract infections, or CAUTIs. The final one, Serious Complications, is based on eight types of injuries, including blood clots, bed sores and falls. Hospitals with a Total HAC Score above 7 will be penalized. Source: Centers For Medicare & Medicaid Services Serious Compli Total Provider cations CLABSI HAC ID Hospital City State County Score Score CAUTI Score Score Penalty 20017 Alaska Regional Hospital Anchorage AK Anchorage 7 9 10 8.625 Penalty 20001 Providence Alaska Medical Center Anchorage AK Anchorage 10 9 6 8.375 Penalty 20027 Mt Edgecumbe Hospital Sitka AK Sitka 7 Not Available Not Available 7 No Penalty 20006 Mat-Su Regional Medical Center Palmer AK Matanuska Susitna 10 6 3 6.425 No Penalty 20012 Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Fairbanks AK Fairbanks North Star 9 8 1 6.075 No Penalty 20018 Yukon Kuskokwim Delta Reg Hospital Bethel AK Bethel 6 Not Available Not Available 6 No Penalty 20024 Central Peninsula General -

Sept. 10-12, 2018

Vol. 119, No. 7 Sept. 10-12, 2018 REFLECTIONS Seventeen years after the attacks on 9/11 — Shanksville remembers By Tina Locurto that day, but incredible good came out in response,” Barnett said THE DAILY COLLEGIAN with a smile. Shanksville is a small, rural town settled in southwestern Heroes in flight Pennsylvania with a population of about 237 people. It has a general Les Orlidge was born and raised in Shanksville. But, his own store, a few churches, a volunteer fire department and a school dis- memories of Sept. 11 were forged from over 290 miles away. trict. American flags gently hang from porch to porch along streets A Penn State alumnus who graduated in 1977, Orlidge had a short with cracked pavement. stint with AlliedSignal in Teterboro, New Jersey. From the second It’s a quiet, sleepy town. floor of his company’s building, he witnessed the World Trade Cen- It’s also the site of a plane crash that killed 40 passengers and ter collapse. crew members — part of what would become the deadliest attack “I watched the tower collapse — I watched the plane hit the on U.S. soil. second tower from that window,” Orlidge said. “I was actually de- The flight, which hit the earth at 563 mph at a 40 degree angle, left pressed for about a year.” a crater 30-feet wide and 15-feet deep in a field in the small town of Using a tiny AM radio to listen for news updates, he heard a re- Shanksville. port from Pittsburgh that a plane had crashed six miles away from Most people have a memory of where they were during the at- Somerset Airport. -

Michigan October 14, 2013

Click here to view the mobile version VOLUME 76 ISSUE 6 Penn State vs. Michigan October 14, 2013 The Letter It was a game that will forever be remembered as the Miracle in Follow us on Beaver Stadium. Twitter and Check out the new The longest game in Penn State Football Letter history wound up as a 43–40 Blog Homecoming upset win over rival Michigan in the fourth overtime of a contest that flowed back and PSU 7 14 3 10 9 -43 forth as fast as the South Jersey UM 10 0 17 7 6 -40 tide. And a deafening White Out crowd played a big role in the stunning Nittany Lion victory over the CONTENTS undefeated No. 16 Wolverines, after four hours and 11 minutes of suspenseful gridiron action. T he Letter N otes from the C uff The season’s first sellout crowd of 107,844 created an atmosphere that O ther Sports inspired the Lions to their most superlative play since last year’s season- N ews of N ote ending overtime triumph over Big Ten champion Wisconsin. Game P hotos After a roller-coaster contest that saw the home team capitalize on Statis tic s three Michigan turnovers to take a 21–10 halftime lead, then fall victim to the running and passing of lean, lanky and light-footed quarterback Devin Gardner, who drove Michigan to a 34–24 advantage in the fourth quarter, PAST ISSUES the Lions had to stage their own thrilling comeback in the final six and one-half minutes of the game. -

Information for Baccalaureate Degree Candidates Spring 2019 Commencement the SMEAL COLLEGE of BUSINESS the Bryce Jordan Center Sunday, May 5, 2019 9:00 A.M

Information for Baccalaureate Degree Candidates Spring 2019 Commencement THE SMEAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS The Bryce Jordan Center Sunday, May 5, 2019 9:00 a.m. Congratulations on achieving your academic goal – conferral of your degree! To participate in the commencement ceremony, it is expected that you have satisfied all University, college, and major requirements in effect at the time of your admission as a degree candidate to the University. ACADMIC REGALIA - (cap and gown) or military uniform is required for participation. Extra adornments on caps and gowns are not permitted. Business professional attire is recommended for all graduates. Dress shoes are appropriate and very high heels or flip flops are not recommended due to safety concerns. THE BRYCE JORDAN CENTER: The doors will open to the public at 7:30 a.m. Graduates will be allowed access to the event floor at 8:00 a.m., via Portal 15 between Gates B and C, and must be seated by 8:45 a.m. You will be directed to sit with your academic department based on your major. Traffic will be heavy prior to the ceremony so please allow extra time. For friends and family who are unable to join us at University Park, the ceremony may be viewed on the Spring Commencement Live Stream http://www.commencement.psu.edu/media/live/ IMPORTANT! You must bring your COMMENCEMENT NOMENCLATOR CARD with you. If your name tends to be mispronounced, you can assist by printing pronunciation cues plainly on the card under your name in pen. (For example: Stankiewicz = Stan-Ka-Vitch). -

The Betrayal of Joe Paterno: How It All Probably Happened

The Betrayal of Joe Paterno: How It All Probably Happened Submitted by jzadmin on Wed, 07/10/2013 - 10:54 “A lie gets half way around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on.” Winston Churchill "In the aftermath of the Freeh Report, the powers that be at present at Penn State should have the good graces to suspend the football program for at least a year, perhaps more.” Bob Costas, July 17th, 2012 “That doesn’t necessarily make sense.” Bob Costas, May 29th, 2013, on the underlying theory of the same Freeh Report A year ago this week the Freeh Report investigation of Penn State and Joe Paterno was released to great fanfare. Largely because of that report, most people seem to think they know the story of the Jerry Sandusky scandal. Almost all of them are at least somewhat mistaken, and most are very wrong about what actually happened. Amazingly, the average media person, because they have a stronger incentive to believe they didn’t blindly perpetrate a false narrative, appears to be even more in the dark than the typical American is about the real truth of this tragedy. After spending most of the past year and a half researching, pondering, and speaking to more people closer to the Jerry Sandusky case than likely anyone else in the world, even I am still not positive that I know exactly what really transpired in the so called “Penn State Scandal.” While I am quite certain that the largely accepted media storyline of some concerted “cover up” by Penn State of Sandusky’s crimes is false, I am somewhat convinced that we may never know for sure precisely what actually did occur. -

Two Talented Qbs, No Controversy Matt Lingerman the Daily Collegian

Follow us on Vol. 119, No. 21 Oct. 29-31, 2018 Race for 34th District ‘uniquely tied’ to student debt By Patrick Newkumet nity to use the Senator’s tenure against er Murphy, said in a statement. “That ‘DEBT’ THE DAILY COLLEGIAN him. can come in the form of direct support “Unfortunately, Pennsylvania has the to public colleges and universities or in State Sen. Jake Corman and Ezra highest average level of student debt for the form of grants to students that have Nanes — opponents in Pennsylvania’s higher education in the entire nation,” demonstrated socio-economic need.” 34th district race — have battled over Nanes said. “Senator Corman, that has Murphy said Nanes “is committed to student debt as the two seek to repre- happened on your watch.” ensuring that oil and natural gas com- sent a constituency deeply tied to Penn Pennsylvania actually has the sec- panies pay their fair share so we have State. ond-highest student debt in the country, money to invest in public education.” Corman has held the seat since 1999, as Forbes estimates the average stu- In his issue statements, it is unclear OUT but it has been in the family much lon- dent accrues $35,759 in loans for higher to what extent Nanes plans on expand- ger. His father, former Sen. Jacob Cor- education. ing the funding of public education. man Jr., took control of the 34th District This can be for any number of factors. An overhaul of the entire system is on June 7, 1977, where he served for The conglomeration of private and unlikely, should he win, as the Penn- over 20 years before being succeeded public universities within each sylvania State Senate is strongly by his son. -

Print Version (Pdf)

Special Collections and University Archives UMass Amherst Libraries UMass Student Publications Collection 1871-2011 27 boxes (16.5 linear foot) Call no.: RG 045/00 About SCUA SCUA home Credo digital Scope Inventory Humor magazines Literary magazines Newspapers and newsletters Yearbooks Other student publications Admin info Download xml version print version (pdf) Read collection overview Since almost the time of first arrival of students at Massachusetts Agricultural College in 1867, the college's students have taken an active role in publishing items for their own consumption. Beginning with the appearance of the first yearbook, put together by the pioneer class during their junior year in 1870 and followed by publication of the first, short-lived newspaper, The College Monthly in 1887, students have been responsible for dozens of publications from literature to humor to a range of politically- and socially-oriented periodicals. This series consists of the collected student publications from Massachusetts Agricultural College (1867-1931), Massachusetts State College (1931-1947), and the University of Massachusetts (1947-2007), including student newspapers, magazines, newsletters, inserts, yearbooks, and songbooks. Publications range from official publications emanating from the student body to unofficial works by student interest groups or academic departments. Links to digitized versions of the periodicals are supplied when available. See similar SCUA collections: Literature and language Mass Agricultural College (1863-1931) Mass State College (1931-1947) UMass (1947- ) UMass students Background Since almost the time of first arrival of students at Massachusetts Agricultural College in 1867, the college's students have taken an active role in publishing items for their own consumption. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1.