Michael Qodby Professorof Historyof Art,University of Capetown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gisèle Wulfsohn's Photographs of HIV/AIDS, 1987-2007

Portraits, Publics and Politics: Gisèle Wulfsohn’s Photographs of HIV/AIDS, 1987-2007 ANNABELLE WIENAND Doctoral Student, Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town Contemporary South African documentary photography is often framed in relation to the history of apartheid and the resistance movement. A number of well-known South African photographers came of age in the 1980s and many of them went on to receive critical acclaim locally and abroad. In comparison, Gisèle Wulfsohn (1957- 2011) has remained relatively unknown despite her involvement in the Afrapix col- lective and her important contribution to HIV/AIDS awareness and education. In focusing on Wulfsohn’s extended engagement with the issue of HIV/AIDS in South Africa, this article aims to highlight the distinctive nature of Wulfsohn’s visualisation of the epidemic. Wulfsohn photographed the epidemic long before there was major public interest in the issue and continued to do so for twenty years. Her approach is unique in a number of ways, most notably in her use of portraiture and her docu- mentation of subjects from varied racial, cultural and socio-economic backgrounds in South Africa. The essay tracks the development of the different projects Wulfsohn embarked on and situates her photographs of HIV/AIDS in relation to her politically informed work of the late 1980s, her personal projects and the relationships she devel- oped with non-governmental organisations.1 Introduction Many commentators have positioned the HIV/AIDS epidemic as the ‘new struggle’ in post-apartheid South Africa. This was most notable during the years before state provision of antiretroviral treatment2 in the public health care system. -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

Between States of Emergency

BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY PHOTOGRAPH © PAUL VELASCO WE SALUTE THEM The apartheid regime responded to soaring opposition in the and to unban anti-apartheid organisations. mid-1980s by imposing on South Africa a series of States of The 1985 Emergency was imposed less than two years after the United Emergency – in effect martial law. Democratic Front was launched, drawing scores of organisations under Ultimately the Emergency regulations prohibited photographers and one huge umbrella. Intending to stifle opposition to apartheid, the journalists from even being present when police acted against Emergency was first declared in 36 magisterial districts and less than a protesters and other activists. Those who dared to expose the daily year later, extended to the entire country. nationwide brutality by security forces risked being jailed. Many Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial, photographers, journalists and activists nevertheless felt duty-bound some for years. Activists were killed, tortured and made to disappear. to show the world just how the iron fist of apartheid dealt with The country was on a knife’s edge and while the state wanted to keep opposition. the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity, many dedicated The Nelson Mandela Foundation conceived this exhibition, Between journalists shone the spotlight on its actions. States of Emergency, to honour the photographers who took a stand On 28 August 1985, when thousands of activists embarked on a march against the atrocities of the apartheid regime. Their work contributed to the prison to demand Mandela’s release, the regime reacted swiftly to increased international pressure against the South African and brutally. -

Afrique Du Sud. Photographie Contemporaine

David Goldblatt, Stalled municipal housing scheme, Kwezidnaledi, Lady Grey, Eastern Cape, 5 August 2006, de la série Intersections Intersected, 2008, archival pigment ink digitally printed on cotton rag paper, 99x127 cm AFRIQUE DU SUD Cours de Nassim Daghighian 2 Quelques photographes et artistes contemporains d'Afrique du Sud (ordre alphabétique) Jordi Bieber ♀ (1966, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) www.jodibieber.com Ilan Godfrey (1980, Johannesburg ; vit à Londres, Grande-Bretagne) www.ilangodfrey.com David Goldblatt (1930, Randfontein, Transvaal, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Kay Hassan (1956, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) Pieter Hugo (1976, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) www.pieterhugo.com Nomusa Makhubu ♀ (1984, Sebokeng ; vit à Grahamstown) Lebohang Mashiloane (1981, province de l'Etat-Libre) Nandipha Mntambo ♀ (1982, Swaziland ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zwelethu Mthethwa (1960, Durban ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zanele Muholi ♀ (1972, Umlazi, Durban ; vit à Johannesburg) Riason Naidoo (1970, Chatsworth, Durban ; travaille à la Galerie national d'Afrique du Sud au Cap) Tracey Rose ♀ (1974, Durban, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Berni Searle ♀ (1964, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit au Cap) Mikhael Subotsky (1981, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Guy Tillim (1962, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Nontsikelelo "Lolo" Veleko ♀ (1977, Bodibe, North West Province ; vit à Johannesburg) Alastair Whitton (1969, Glasgow, Ecosse ; vit au Cap) Graeme Williams (1961, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Références bibliographiques Black, Brown, White. Photography from South Africa, Vienne, Kunsthalle Wien 2006 ENWEZOR, Okwui, Snap Judgments. New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, cat. expo. 10.03.-28.05.06, New York, International Center of Photography / Göttingen, Steidl, 2006 Bamako 2007. -

2017 07 31 Leslie Wilson Dissertation Past Black And

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PAST BLACK AND WHITE: THE COLOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1994-2004 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY LESLIE MEREDITH WILSON CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 PAST BLACK AND WHITE: THE COLOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1994-2004 * * * LIST OF FIGURES iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xv ABSTRACT xx PREFACE “Colour Photography” 1 INTRODUCTION Fixing the Rainbow: 8 The Development of Color Photography in South Africa CHAPTER 1 Seeking Spirits in Low Light: 40 Santu Mofokeng’s Chasing Shadows CHAPTER 2 Dignity in Crisis: 62 Gideon Mendel’s A Broken Landscape CHAPTER 3 In the Time of Color: 100 David Goldblatt’s Intersections CHAPTER 4 A Waking City: 140 Guy Tillim’s Jo’burg CONCLUSION Beyond the Pale 182 BIBLIOGRAPHY 189 ii LIST OF FIGURES All figures have been removed for copyright reasons. Preface i. Cover of The Reflex, November 1935 ii. E. K. Jones, Die Voorloper, 1939 iii. E. B. King, The Reaper, c. 1935 iv. Will Till, Outa, 1946 v. Broomberg and Chanarin, Kodak Ektachrome 34 1978 frame 4, 2012 vi. Broomberg and Chanarin, Shirley 2, 2012 vii. Broomberg and Chanarin, Ceramic Polaroid Sculpture, 2012. viii. Installation view of Broomberg and Chanarin, The Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement at Goodman Gallery, 2013. ix. “Focusing on Black South Africa: Returning After 8 Years, Kodak Runs into White Anger” illustration, by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., The New York Times x. Gisèle Wulfsohn, Domestic worker, Ilovo, Johannesburg, 1986. Introduction 0.1 South African Airways Advertisement, 1973. -

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger BOSCH • Julian COBBING • Gille DE VLIEG • Brett ELOFF • Don EDKINS • Ellen ELMENDORP • Graham GODDARD • Paul GRENDON • George HALLETT • Dave HARTMAN • Steven HILTON-BARBER • Mike HUTCHINGS • Lesley LAWSON • Chris LEDOCHOWSKI • John LIEBENBERG • Herbert MABUZA • Humphrey Phakade "Pax" MAGWAZA • Kentridge MATABATHA • Jimi MATTHEWS • Rafs MAYET • Vuyi Lesley MBALO • Peter MCKENZIE • Gideon MENDEL • Roger MEINTJES • Eric MILLER • Santu MOFOKENG • Deseni MOODLIAR (Soobben) • Mxolisi MOYO • Cedric NUNN • Billy PADDOCK • Myron PETERS • Biddy PARTRIDGE • Chris QWAZI • Jeevenundhan (Jeeva) RAJGOPAUL • Wendy SCHWEGMANN • Abdul SHARIFF • Cecil SOLS • Lloyd SPENCER • Guy TILLIM • Zubeida VALLIE • Paul WEINBERG • Graeme WILLIAMS • Gisele WULFSOHN • Anna ZIEMINSKI • Morris ZWI 1 AFRAPIX PHOTOGRAPHERS, BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES • Joe ALFERS Joe (Joseph) Alfers was born in 1949 in Umbumbulu in Kwazulu Natal, where his father was the Assistant Native Commissioner. He attended school and university in Pietermaritzburg, graduating from the then University of Natal with a BA.LLB in 1972. At University, he met one of the founders of Afrapix, Paul Weinberg, who was also studying law. In 1975 he joined a commercial studio in Pietermaritzburg, Eric’s Studio, as an apprentice photographer. In 1977 he joined The Natal Witness as a photographer/reporter, and in 1979 moved to the Rand Daily Mail as a photographer. In 1979, Alfers was offered a position as Photographer/Fieldworker at the National University of Lesotho on a research project, Analysis of Rock Art in Lesotho (ARAL) which made it possible for him to evade further military service. The ARAL Project ran for four years during which time Alfers developed a photographic recording system which resulted in a uniform collection of 35,000 Kodachrome slides of rock paintings, as well as 3,500 pages of detailed site reports and maps. -

Portrait and Documentary Photography in Post-Apartheid South Africa: (Hi)Stories of Past and Present

Portrait and documentary photography in post-apartheid South Africa: (hi)stories of past and present Paula Alexandra Horta Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Cultural Studies at the University of London Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths College Supervision: Dr. Jennifer Bajorek 2011 Declaration This thesis is the result of work carried out by me, and has been written by me. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been acknowledged. Signed: ……………………………………………………… Date: ………………………………………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis will explore how South African portrait and documentary photography produced between 1994 and 2004 has contributed to a wider understanding of the country‘s painful past and, for some, hopeful, for others, bleak present. In particular, it will examine two South African photographic works which are paradigmatic of the political and social changes that marked the first decade after the fall of apartheid, focusing on the empowerment of both photographers and subjects. The first, Jillian Edelstein‘s (2001) Truth & Lies: Stories from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, captures the faces and records the stories of perpetrators and victims who gave their testimonies to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa from 1996 to 2000. The second, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin‘s (2004a) Mr. Mkhize‟s Portrait & Other Stories from the New South Africa, documents the changed/ unchanged realities of a democratic country ten years after apartheid. The work of these photographers is showcased for its specificity, historicity and uniqueness. In both works the images are charged with emotion. Viewed on their own — uncaptioned — the photographs have the capacity to unsettle the viewer, but in both cases a compelling intermeshing of image and text heightens their resonance and enables further possibilities for interpretation. -

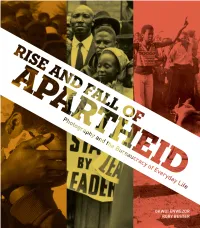

Rise and Fall of Apartheid

Events in the 1980s represent a significant coming to In light of these sweeping global changes, the scene in RISE AND FALL OF APARTHEID terms with the apartheid state at every level.8 It is within this Cape Town on that day in parliament can be properly encap- PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE BUREAUCRACY OF EVERYDAY LIFE context that the Detainees’ Hunger Strike at Diepkloof Prison sulated as an appointment with history. The announcement Okwui Enwezor in Soweto, which started on January 23, 1989, was pivotal in of the end of apartheid was part of a carefully choreographed F. W. de Klerk’s act of rapprochement that occurred a year lat- and coordinated plan: first the unbanning of the African Na- er. The strike appeared to be the trigger that finally brought tional Congress (ANC), Pan-African Congress (PAC), South Apartheid is Violence. Violence is used to subjugate and to deny basic rights to black people.1 But no matter how the policy of the apartheid government to the table for serious negotiation. African Communist Party (SACP), Congress of South African apartheid has been applied over the years, both black and white democrats have actively opposed it. It is in the struggle for Twenty prisoners detained under the 1986 state of emergen- Trade Unions (COSATU), and other political, labor, and civic justice that the gulf between artists, writers, and photographers and the people has been narrowed. cy laws began a hunger strike with an unequivocal demand: organizations; the lifting of the state of emergency; and the —Omar Badsha, South Africa: The Cordoned Heart, 1986 the unconditional release of all political prisoners. -

Between States of Emergency

© PAUL VELASCO © PAUL The Nelson Mandela Foundation was established by Madiba to continue his life’s work to deepen democracy, build peace and advance human rights. We continue Madiba’s work through an archival and research programme, host dialogues on social issues that Madiba cared deeply about and we convene the Mandela Day programme to support his ongoing humanitarian efforts. BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY F: NelsonMandela 107 Central Street, Tel: +27 (0)11 547 5600 www.nelsonmandela.org PHOTOGRAPHERS IN ACTION 1985 – 1990 F: NelsonMandelaCentreOfMemory Houghton, Fax: +27 (0)11 728 1111 [email protected] T: @NelsonMandela Johannesburg, 2198 Exhibition Credits: Curator: Robin Comley | Printer: Lightfarm and Southern Editions | Exhibition Designer: Sam Colyn, C3 Designs | Manufacturer: Progroup | Framer: Frame Depot | Visitors’ Guide Design: Cube Design © Nelson Mandela Foundation THE NELSON MANDELA FOUNDATION Nelson Mandela was South Africa’s first democratically elected President. On 9 May 1994, soon after our landmark election results were in, he was unanimously elected President by I reiterate our call for, inter alia, South Africa’s new Members of Parliament. the immediate ending of the The next day Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela Nelson Mandela, providing an integrated He donated his personal papers to was sworn in at an inauguration ceremony public information resource on his life and the Nelson Mandela Foundation and State of Emergency and the freeing at the Union Buildings in Pretoria. times, and by convening dialogue around mandated it to document his life and He vowed to only serve one term as critical social issues. times. He also assigned it to promote of all, and not only some, political President and in 1999 he stepped down his legacy by creating a safe space for to make way for President Thabo Mbeki.