Adam Driscoll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth II 1.4.1 - Manual Install Guide

Myth II 1.4.1 - Manual Install Guide About | Installation | Online Gameplay | Credits | Changelog About Myth II 1.4.1 Myth v1.4 features over 100 enhancements, bug fixes and new features to Myth II: Soulblighter, in the areas of: graphics; interface improvements; elimination of plugin lag; elimination of chat lag; elimination of the 'walking bug', new mapmaking features; AI improvements and bug fixes; optional vTFL (virtual TFL) gameplay, which effectively brings both games and communities to the same program; and much, much more. 1.4.1 adds several improvements over 1.4, including faster OpenGL and Direct3D; 1.3/1.4 film support; melee fixes; better widescreen zooming; separated vTFL and anticlump options; F10 now a toggle; along with many more gameplay fixes and refinements. Installation Steps 1. In this archive you will find an application/executable; put it in your Myth II directory. Overwrite the old file that is present. 2. Also in this archive is a “Myth 2 EEL” file. Put it in the same directory as the application/executable. This file is needed only if you intend to use MariusNet, but it will not hurt PlayMyth users. 3. You will have a “For plugins” folder in the same directory as your new Myth II application/executable. Move all the files from the plugins directory in this archive to that directory. Do not move over the folder itself or you will overwrite all of your plugins. Note: If you are using the Chimera interface do not copy over the "Patch 1.4 Interface" file or you will overwrite the Chimera Interface. -

A Guide to the Josh Brandt Video Game Collection Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute DigitalCommons@WPI Collection Guides CPA Collections 2014 A guide to the Josh Brandt video game collection Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/cpa-guides Suggested Citation , (2014). A guide to the Josh Brandt video game collection. Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/cpa-guides/4 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the CPA Collections at DigitalCommons@WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collection Guides by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WPI. Finding Aid Report Josh Brandt Video Game Collection MS 16 Records This collection contains over 100 PC games ranging from 1983 to 2002. The games have been kept in good condition and most are contained in the original box or case. The PC games span all genres and are playable on Macintosh, Windows, or both. There are also guides for some of the games, and game-related T-shirts. The collection was donated by Josh Brandt, a former WPI student. Container List Container Folder Date Title Box 1 1986 Tass Times in Tonestown Activision game in original box, 3 1/2" disk Box 1 1989 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Curse of the Azure Bonds 5 1/4" discs, form IBM PC, in orginal box Box 1 1988 Life & Death: You are the Surgeon 3 1/2" disk and related idtems, for IBM PC, in original box Box 1 1990 Spaceward Ho! 2 3 1/2" disks, for Apple Macintosh, in original box Box 1 1987 Nord and Bert Couldn't Make Heads or Tails of It Infocom, 3 1/2" discs, for Macintosh in original -

Halo Engine Ancestry Statistics

HALO ENGINE ANCESTRY The Halo 2 engine is a direct-line descendant of the 1992 Pathways into Darkness engine originally written by Bungie for 68000 Macs using MPW and C. Not much remains except math functions and overall architecture, but the engine definitely has old roots. The path of descent runs through PiD to Marathon to Myth to Halo. In recent years it has shifted away from being primarily a player-driven renderer to being primarily a world simulation. I’m going to talk about two main philosophies that you can trace through the engine and most of its components. 1. The unified resource model, editing and import tools, general memory layout, filesystem and streaming architecture. 2. Our approach to runtime data organization, memory allocation and world state. STATISTICS • 1.5M lines in 3,624 files for 52.9MB of code (mostly C, some C++, very little asm) • Compile time for clean build of typical development build: 7:39 • Compile time for final shipping build (includes LTCG): 10:06 • Final executable size: 4,861,952 bytes • Total assets under source control: 70 GB not counting localization • Time to load a level, development build: 4 minutes • Time to compile a level for shipping build: 9 minutes • Time for complete build of all binaries on build farm: 18 minutes • Time for complete build of all map resources on build farm: 53 minutes • Size of final game: 4.2 GB • Development time: 34 months • Breakdown of production staff (56): o 17 engineers o 11 environment artists o 8 game artists o 7 designers o 6 animators o 3 producers o 3 sound designers o 1 technical artist • Breakdown of support staff (59): o 2 administrative o 8 web / community o 5 test engineers o 10 test staff o 20 hourly testers o 14 localization testers RESOURCE MODEL We use a unified model for the majority of our game resource data called “tags”. -

GAME DEVELOPERS a One-Of-A-Kind Game Concept, an Instantly Recognizable Character, a Clever Phrase— These Are All a Game Developer’S Most Valuable Assets

HOLLYWOOD >> REVIEWS ALIAS MAYA 6 * RTZEN RT/SHADER ISSUE AUGUST 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SIGGRAPH 2004 >>DEVELOPER DEFENSE >>FAST RADIOSITY SNEAK PEEK: LEGAL TOOLS TO SPEEDING UP LIGHTMAPS DISCREET 3DS MAX 7 PROTECT YOUR I.P. WITH PIXEL SHADERS POSTMORTEM: THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY []CONTENTS AUGUST 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 7 FEATURES 14 COPYRIGHT: THE BIG GUN FOR GAME DEVELOPERS A one-of-a-kind game concept, an instantly recognizable character, a clever phrase— these are all a game developer’s most valuable assets. To protect such intangible properties from pirates, you’ll need to bring out the big gun—copyright. Here’s some free advice from a lawyer. By S. Gregory Boyd 20 FAST RADIOSITY: USING PIXEL SHADERS 14 With the latest advances in hardware, GPU, 34 and graphics technology, it’s time to take another look at lightmapping, the divine art of illuminating a digital environment. By Brian Ramage 20 POSTMORTEM 30 FROM BUNGIE TO WIDELOAD, SEROPIAN’S BEAT GOES ON 34 THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ A decade ago, Alexander Seropian founded a SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY one-man company called Bungie, the studio that would eventually give us MYTH, ONI, and How do you give a player that vicarious presence in an imaginary HALO. Now, after his departure from Bungie, environment—that “you-are-there” feeling that a good movie often gives? he’s trying to repeat history by starting a new Zombie’s answer was to adopt many of the standard movie production studio: Wideload Games. -

Indiana University Maurer School of Law-Bloomington Legal Studies Research Paper Series

INDIANA UNIVERSITY MAURER SCHOOL OF LAW-BLOOMINGTON LEGAL STUDIES RESEARCH PAPER SERIES Research Paper Number 165 April 2010 JUDICIAL POLITICS, THE RULE OF LAW AND THE FUTURE OF AN ERMINE MYTH Charles Gardner Geyh This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1598454 Judicial Politics, the Rule of Law and the Future of an Ermine Myth Charles Gardner Geyh1 According to a Renaissance myth, the ermine would rather die than soil its pristine, white coat. English and later American judges would adopt the ermine as a symbol of the judiciary’s purity and commitment to the rule of law. This “ermine myth” remains central to the legal establishment’s conception of the judicial role: independent judges, the argument goes, disregard extralegal influences and strictly follow the law. In contrast, political scientists had long theorized that judicial independence liberates judges to disregard the law and substitute their extralegal policy preferences. A recent spate of interdisciplinary research, however, has led to an emerging consensus among law professors and political scientists that judges are subject to a complex array of legal and extralegal influences. This emerging scholarly consensus stands in stark contrast to the simplistic and dichotomous public policy debate, where court critics seek to control “activist” judges, whom they accuse of ignoring the law and legislating from the bench, while the legal establishment defends judges and their independence from attack, citing the ermine myth that independent judges are committed solely to upholding the law. This article explores the future of the ermine myth that has guided the legal establishment for centuries. -

Video Game Collection MS 17 00 Game This Collection Includes Early Game Systems and Games As Well As Computer Games

Finding Aid Report Video Game Collection MS 17_00 Game This collection includes early game systems and games as well as computer games. Many of these materials were given to the WPI Archives in 2005 and 2006, around the time Gordon Library hosted a Video Game traveling exhibit from Stanford University. As well as MS 17, which is a general video game collection, there are other game collections in the Archives, with other MS numbers. Container List Container Folder Date Title None Series I - Atari Systems & Games MS 17_01 Game This collection includes video game systems, related equipment, and video games. The following games do not work, per IQP group 2009-2010: Asteroids (1 of 2), Battlezone, Berzerk, Big Bird's Egg Catch, Chopper Command, Frogger, Laser Blast, Maze Craze, Missile Command, RealSports Football, Seaquest, Stampede, Video Olympics Container List Container Folder Date Title Box 1 Atari Video Game Console & Controllers 2 Original Atari Video Game Consoles with 4 of the original joystick controllers Box 2 Atari Electronic Ware This box includes miscellaneous electronic equipment for the Atari videogame system. Includes: 2 Original joystick controllers, 2 TAC-2 Totally Accurate controllers, 1 Red Command controller, Atari 5200 Series Controller, 2 Pong Paddle Controllers, a TV/Antenna Converter, and a power converter. Box 3 Atari Video Games This box includes all Atari video games in the WPI collection: Air Sea Battle, Asteroids (2), Backgammon, Battlezone, Berzerk (2), Big Bird's Egg Catch, Breakout, Casino, Cookie Monster Munch, Chopper Command, Combat, Defender, Donkey Kong, E.T., Frogger, Haunted House, Sneak'n Peek, Surround, Street Racer, Video Chess Box 4 AtariVideo Games This box includes the following videogames for Atari: Word Zapper, Towering Inferno, Football, Stampede, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ms. -

Destiny Grosses More Than $325 Million Worldwide in First Five Days

Destiny Grosses More Than $325 Million Worldwide in First Five Days Players Logged More Than 100 Million Hours of Online Play in the First Week Destiny Becomes Best-Selling New Video Game Franchise Launch of All Time SANTA MONICA, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Activision Publishing, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, Inc. (Nasdaq: ATVI), announced today that its highly anticipated new franchise Destiny sold-through more than $325 million worldwide in its first five days, according to Chart-Track, first parties, retail customer sell-through information and Activision Blizzard internal estimates. According to Bungie, Destiny players logged more than 100 million hours of online play by the end of the first week and participated in 137 million activities. The game has won over 180 awards and nominations to date. "Destiny fans played more than 100 million hours of the game in the first week. That's on par with the engagement levels of our most popular Call of Duty® games, which obviously is an industry leader," said Eric Hirshberg, CEO, Activision Publishing. "Millions of gamers are having a great time playing Destiny and can't put down their controllers. And this is just the beginning. Destiny is a platform that will grow and evolve and we will continue to work closely with our partners at Bungie to bring a long line of new experiences and content to life in the game." Hailed by Game Informer Magazine as "one of the first true event games of this new generation," and lauded by Yahoo! Games as "gorgeous, slick, and finely tuned, a technical knockout," Destiny casts players as a Guardian of the last city on Earth, able to explore the ancient ruins of our solar system in a social, living universe filled with other players. -

Exploring Skill Sets for Computer Game Design Programs Bungie, Inc

Exploring Skill Sets for Computer Game Design Programs Bungie, Inc. Employees Share Their Insights by Markus Geissler, Professor and Deputy Sector Navigator, ICT/Digital Media, Greater Sacramento Region Abstract: Based upon several responses from employees at Bungie, Inc., a developer of computer games based in Seattle, to both general and specific questions about the skills sets required for students who wish to work in the computer game industry, technical knowledge, especially in computer programming, but, more importantly, solid interpersonal skills, the ability to think as part of a team consisting of individuals with varying skill sets, and the strength to solve complex problems should be essential program student learning outcomes (PSLOs) for Computer Game Design or similar academic programs. To that end academic program designers should strongly consider an interdisciplinary preparation which includes coursework that addresses both technical and professional PSLOs and which may be offered by content experts across multiple academic departments. Author’s note: In May 2019 the members of Cosumnes River College’s (CRC) Computer Information Science faculty discussed whether or not to add a Game Design component to the department’s course offerings, possibly to complement existing programs at nearby colleges. To better inform the discussion I volunteered to get some industry input via a family friend who works at Bungie, Inc., an American video game developer based in Bellevue, WA which is the developer of computer games such as Destiny, Halo, Myth, Oni, and Marathon. Several Bungie employees were kind enough to respond first to my initial request for a conversation and then specific questions by CRC’s CIS faculty members which I forwarded to the folks at Bungie. -

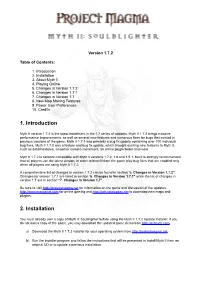

Myth II 1.7.2 Read Me

Version 1.7.2 Table of Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Installation 3. About Myth II 4. Playing Online 5. Changes in Version 1.7.2 6. Changes in Version 1.7.1 7. Changes in Version 1.7 8. New Map Making Features 9. Power User Preferences 10. Credits 1. Introduction Myth II version 1.7.2 is the latest installment in the 1.7 series of updates. Myth II 1.7.2 brings massive performance improvements, as well as several new features and numerous fixes for bugs that existed in previous versions of the game. Myth II 1.7.1 was primarily a bug fix update containing over 100 individual bug fixes. Myth II 1.7.0 was a feature and bug fix update, which brought exciting new features to Myth II, such as detail textures, smoother camera movement, an online plugin finder and more. Myth II 1.7.2 is network compatible with Myth II versions 1.7.x, 1.6 and 1.5.1, but it is strongly recommended that all players use the latest version, in order to benefit from the game play bug fixes that are enabled only when all players are using Myth II 1.7.2. A comprehensive list of changes in version 1.7.2 can be found in section “5. Changes in Version 1.7.2”. Changes for version 1.7.1 are listed in section “6. Changes in Version 1.7.1” while the list of changes in version 1.7 are in section “7. Changes in Version 1.7”. -

Norse Mythology in Video Games: Part of Immanent Nordic Regional Branding

Norse mythology in video games: part of immanent Nordic regional branding. Lysiane Lasausse Master’s Thesis Master of European and Nordic Studies Department of Area and Cultural Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Helsinki Spring 2018 Supervisor: Peter Stadius. Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Laitos – Institution – Department Faculty Department of Area and Cultural Studies Faculty of Arts Tekijä – Författare – Author Lysiane Lasausse Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Norse mythology in video games: part of immanent Nordic regional branding. Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject European and Nordic Studies Työn laji – Arbetets art – Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Level year Master 04/2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract An estimated 2,5 billion players in 2017, 143 billion revenues by 2020, video games have conquered the market and the homes of almost half the population. Often considered a niche media, recent figures prove that the market keeps on growing. When looking at it from a marketing point of view, video games appear to be the golden goose. Nation branding is all about marketing: selling the best of one’s nation to other nations to attract investors, tourists, brains and technology. Why then, not consider video games as a mean to brand a nation? With such a large scale of influence and potential, one could argue video games seem like the perfect opportunity to make a nation known. Norse mythology did not -and does not- have that many supporters, but its influence is far-reaching: in movies, books, series and video games, it has been a source of inspiration for decades. Video games with Norse elements have been quite popular, especially since 2015. -

An Analysis of the Hero Myth in Fromsoftware's Dark Souls Series

1 Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Mapping Myth: an Analysis of the Hero Myth in FromSoftware’s Dark Souls Series 2015-2016 Paper submitted in partial Supervisor: fulfillment of the requirements for Prof. Dr. Tobi Smethurst the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Niels Schollaert 2 3 0. Acknowledgements After a whole year, I have finally finished my dissertation, which marks both the end of my master’s degree and simultaneous departure from Ghent University. It goes without saying that such a case of extensive writing is not a process which takes place overnight, nor is it exclusively the result of my own individual labor. Rather, a myriad of people has helped in the construction if this thesis, either directly or indirectly. I therefore would like to devote the following page to express my sincerest gratitude to those people who have been of considerable help, and without whom I would not have been able to complete this dissertation. First, I would like to thank prof. dr. Tobi Smethurst for the help she provided throughout all stages of writing, and more importantly, for granting me the opportunity to write on a subject I have been passionate about all my life. Second, my gratitude goes out to prof. dr. Nadia Sels, whose recommendations of academic publications concerning mythology have greatly aided me in the analytical sections of my work. Finally, I truly appreciate the support of my friends and family. I cannot even begin to describe all the various ways in which they have encouraged me during the past several years. -

Reconstruction of Norse Myth in Videogames: the Case of God of War

Reconstruction of Norse Myth in videogames: the case of God of War Ekaterina Koshkina A research paper submitted to the University of Dublin in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Interactive Digital Media May, 2020 Declaration I have read and I understand the plagiarism provisions in the General Regulations of the University Calendar for the current year, found at: http://www.tcd.ie/calendar I have also completed the Online Tutorial on avoiding plagiarism ‘Ready, Steady, Write’, located at http://tcdie.libguides.com/plagiarism/readysteadywrite I declare that the work described in this research Paper is, except where otherwise stated, entirely my own work and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university. Signed: ___________________ Ekaterina Koshkina 31th May 2020 2 Permission to lend and/or copy I agree that Trinity College Library may lend or copy this Research Paper upon request. Signed: ___________________ Ekaterina Koshkina 31th May 2020 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor and the course director, Dr.Mads Haahr, for this unique opportunity to be a part of IDM programme here in Ireland, and for his patience and invaluable guidance throughout the research process. I would also like to thank my classmates and IDM professors for making this year a truly one-of-a-kind experience of my life. 4 Abstract The present study aimed to address the issue of modern myth making in interactive digital media, more specifically, myth reconstruction and myth adaptation in video games. Having carried out extensive analysis of corresponding literature, we have conducted a case study of God of War (2018).