That Was Then, This Is Now: Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manager Cascade, Edit, Or Discontinue Goal(S) in Workday

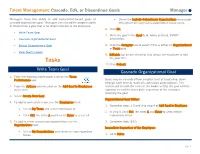

Talent Management: Cascade, Edit, or Discontinue Goals Manager Managers have the ability to add department-based goals or • Check the Include Subordinate Organizations to cascade cascade organization goal. Managers can also edit in-progress goals throughout all supervisory organization below yours. or discontinue a goal that is no longer relevant to the employee. 6. Click OK. • Write Team Goal 7. Write the goal in the Goal field. Add a detailed, SMART • Cascade Organizational Goal description. • Edit or Discontinue a Goal 8. Click the Category box to select if this is either an Organizational or Team goal. • View Team’s Goals 9. Editable will be pre-selected. This allows the employee to edit Tasks the goal title. 10. Click Submit. Write Team Goal Cascade Organizational Goal 1. From the Workday home page, click on the Team Performance app. Goals may be cascaded from a higher level of leadership, down through each level to reach all supervisory organizations. This 2. From the Actions column, click on the Add Goal to Employees section will include the steps of the leader writing the goal and the menu item. approval step of the immediate supervisor of the employee receiving the goal. 3. Select Create New Goal. Organizational Goal Writer: 4. To add to immediate team, use the Employees field: 1. Complete steps 1-3 and skip step 4 of Add Goal to Employee. • Select My Team and select individuals or 2. In step 5, click Ctrl, the letter A and Enter to select entire • Click Ctrl, the letter A and then hit Enter to select all. -

Personal Goals, Life Meaning, and Virtue: Wellsprings of a Positive Life

5 PERSONAL GOALS, LIFE MEANING, AND VIRTUE: WELLSPRINGS OF A POSITIVE LIFE ROBERT A. EMMONS Nothing is so insufferable to man as to be completely at rest, without passions, without business, without diversion, without effort. Then he feels his nothingness, his forlornness, his insufficiency, his weakness, his emptiness. (Pascal, The Pensees, 1660/1950, p. 57). As far as we know humans are the only meaning-seeking species on the planet. Meaning-making is an activity that is distinctly human, a function of how the human brain is organized. The many ways in which humans conceptualize, create, and search for meaning has become a recent focus of behavioral science research on quality of life and subjective well-being. This chapter will review the recent literature on meaning-making in the context of personal goals and life purpose. My intention will be to document how meaningful living, expressed as the pursuit of personally significant goals, contributes to positive experience and to a positive life. THE CENTRALITY OF GOALS IN HUMAN FUNCTIONING Since the mid-1980s, considerable progress has been made in under- standing how goals contribute to long-term levels of well-being. Goals have been identified as key integrative and analytic units in the study of human Preparation of this chapter was supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. I would like to express my gratitude to Corey Lee Keyes and Jon Haidt for the helpful comments on an earlier draft of this chapter. 105 motivation (see Austin & Vancouver, 1996; Karoly, 1999, for reviews). The driving concern has been to understand how personal goals are related to long-term levels of happiness and life satisfaction and how ultimately to use this knowledge in a way that might optimize human well- being. -

Management by Objectives: Advantages, Problems, Implications for Community Colleges

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 057 792 JC 720 028 AUTHOR Collins, Robert W. TITLE Management by Objectives: Advantages, Problems, Implications for Community Colleges. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 20p.; Seminar paper EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Administrative Principles; Decision Making; *Educational Administration; *Junior Colleges; *Management; *Management Development; *Management Systems; Objectives ABSTRACT Not new in principle, management by objectives (MBO) focuses on the goals of an institution stated as end accomplishments. Community college administrators have been attracted by the reputed benefits of MBO: increased productivity, improved planning, maximized profits, objective managerial evaluation, and improved participant morale. This paper summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of MBO learned and reported from business and industry. Problems encountered in MBO programs include: lack of total organizational commitment, lack of prerequisites to implementation, failpre to integrate individual and organizational goals, overemph sis on measurable goal attainment, and inadequacies in performance a praisal. To be most effective in community colleges, MBO must have the total backing of board members and the president. Furthermore, the school must be prepared to commit extra time to implement MBO. The major determinant of the success or failure of MBO type programs is largely a result of its acceptance by users. (IA1 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE Of'FICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT POINTS 0:' VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DC NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL. -FFICE OF EDU- "CATION.POSITION OR POLICY. CNJ MANAGEMENT BY OBJECTIVES: ADVANTAGES, PROBLEMS, IMPLICATIONS FOR COMMUNITY COLLEGES BY: Robert W. -

An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis

Modern Psychological Studies Volume 5 Number 2 Article 3 1997 An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Minier, Samuel (1997) "An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis," Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol5/iss2/3 This articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Magazines, and Newsletters at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Psychological Studies by an authorized editor of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Eclectic approaches to psychotherapy often lack cohesion due to the focus on technique and procedure rather than theory and wholeness of both the person and of the therapy. A synthesis of Jungian and existential therapies overcomes this trend by demonstrating how two theories may be meaningfully integrated The consolidation of the shared ideas among these theories reveals a notion of "authentic wholeness' that may be able to stand on its own as a therapeutic objective. Reviews of both analytical and existential psychology are given. Differences between the two are discussed, and possible reconciliation are offered. After noting common elements in these shared approaches to psychotherapy, a hypothetical therapy based in authentic wholeness is explored. Weaknesses and further possibilities conclude the proposal In the last thirty years, so-called "pop Van Dusen (1962) cautions that the differences among psychology" approaches to psychotherapy have existential theorists are vital to the understanding of effectively demonstrated the dangers of combining existentialism, that "[when] existential philosophy has disparate therapeutic elements. -

CONDUCTING a GOAL-SETTING DISCUSSION Conducting Goal Setting

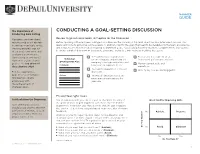

MANAGER GUIDE The Importance of CONDUCTING A GOAL-SETTING DISCUSSION Conducting Goal Setting Managers and their direct Review Organizational Goals to Prepare for the Discussion reports need to collaborate Before speaking with employees, managers should review the company’s top-level objectives and determine how your own in setting meaningful goals, goals contribute to achieving business goals. In addition, identify the goals that need to be delegated to the team, and provide tracking progress against direct reports with the information required to draft their goals. You should advise the reports to complete the following steps those goals over time, and to create a draft of their performance goals, strategies, and tactics before the goal-setting discussion: evaluating performance. Connecting an employee’s Re-read the mission and vision Review any development areas Individual work with organizational for the company; understand the from recent performance reviews. Development Plan company’s strategic objectives and goals is the top driver of Review current goals and Comments how your job supports them. discretionary effort. aspirations. Re-read the department’s mission Identify any new overarching goals. For the organization, and vision. goal-driven performance Actions Review job description and any management aligns performance expectations for employees with your role. the achievement of strategic goals. Ensure Meaningful Goals Set Goals from the Beginning You should work with your direct report to check the accuracy of Goals Grid for Improving Skills the goals and assess goal alignment with those of peers and the Goal-setting discussions department. In addition, you should ensure that the goals support should occur shortly after the the employees’ development goals based on any recent performance performance reviews or as an feedback. -

Theory in the Practice of Psychotherapy

CAE Theory in the Practice of Psychotherapy Muay owe, M.. There are striking discrepancies between theory and practice in psychother- apy. The therapist's theoretical assumptions about the nature and origin of emotional illness serve as a blueprint that guides his thinking and actions during psychotherapy. This has always been so, even though "theory" and " therapeutic method" have not always been clearly defined. Primitive medi- cine men who believed that emotional illness was the result of evil spirits had some kind of theoretical notions about the evil spirits that guided their therapeutic method as they attempted to free the person of the spirits. I believe that theory is important now even though it might be difficult to define the specific connections between theory and practice. I have spent almost three decades on clinical research in psychotherapy. A major part of my effort has gone toward clarifying theory and also toward developing therapeutic approaches consistent with the theory. I did this in the belief it would add to knowledge and provide better structure for research. A secondary gain has been an improvement in the predictability and outcome of therapy as the therapeutic method has come into closer proximity with the theory. Here I shall first present ideas about the lack of clarity between theory and practice in all kinds of psychotherapy; in the second section I will deal specifically with family therapy. In discussing my own Family Systems theory, certain parts will be presented almost as previ- ously published (1,2). Other parts will be modified slightly, and some new concepts will be added. -

About Psychoanalysis

ABOUT PSYCHOANALYSIS What is psychoanalysis? What is psychoanalytic treatment for? Freud’s major discoveries and innovations • The Unconscious • Early childhood experiences • Psychosexual development • The Oedipus complex • Repression • Dreams are wish-fulfilments • Transference • Free association • The Ego, the Id and the Super-Ego Major discoveries and additions to psychoanalytic theory since Freud: the different strands and schools within psychoanalysis today • Classical and contemporary Freudians • Sándor Ferenczi • Ego-Psychology • Classical and contemporary Kleinians • The Bionian branch of the Kleinian School • Winnicott’s branch of the Object-Relations Theory • French psychoanalysis • Self-Psychology • Relational Psychoanalysis The core psychoanalytic method and setting • Method • Setting Various Psychoanalytic Treatment Methods (adult, children, groups, etc) • Psychoanalysis • Psychoanalytic or psychodynamic psychotherapy • Children and adolescents • Psychoanalytic psychodrama • Psychoanalytic Couples- and Family-Psychotherapy • Psychoanalytic Groups Psychoanalytic training Applied psychoanalysis The IPA, its organisation and ethical guidelines Where to encounter psychoanalysis? What is psychoanalysis? Psychoanalysis is both a theory of the human mind and a therapeutic practice. It was founded by Sigmund Freud between 1885 and 1939 and continues to be developed by psychoanalysts all over the world. Psychoanalysis has four major areas of application: 1) as a theory of how the mind works 2) as a treatment method for psychic problems 3) as a method of research, and 4) as a way of viewing cultural and social phenomena like literature, art, movies, performances, politics and groups. What is psychoanalytic treatment for? Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy are for those who feel caught in recurrent psychic problems that impede their potential to experience happiness with their partners, families, and friends as well as success and fulfilment in their work and the normal tasks of everyday life. -

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Stroke Rehabilitation

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Stroke Rehabilitation Amy Quilty OT Reg. (Ont.), Occupational Therapist Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Certificate Program, University of Toronto Quinte Health Care: [email protected] Learning Objectives • To understand that CBT: • has common ground with neuroscience • principles are consistent with stroke best practices • treats barriers to stroke recovery • is an opportunity to optimize stroke recovery Question? Why do humans dominate Earth? The power of THOUGHT • Adaptive • Functional behaviours • Health and well-being • Maladaptive • Dysfunctional behaviours • Emotional difficulties Emotional difficulties post-stroke • “PSD is a common sequelae of stroke. The occurrence of PSD has been reported as high as 30–60% of patients who have experienced a stroke within the first year after onset” Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Mood, Cognition and Fatigue Following Stroke practice guidelines, update 2015 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijs.12557/full • Australian rates: (Kneeborne, 2015) • Depression ~31% • Anxiety ~18% - 25% • Post Traumatic Stress ~10% - 30% • Emotional difficulties post-stroke have a negative impact on rehabilitation outcomes. Emotional difficulties post-stroke: PSD • Post stroke depression (PSD) is associated with: • Increased utilization of hospital services • Reduced participation in rehabilitation • Maladaptive thoughts • Increased physical impairment • Increased mortality Negative thoughts & depression • Negative thought associated with depression has been linked to greater mortality at 12-24 months post-stroke Nursing Best Practice Guideline from RNAO Stroke Assessment Across the Continuum of Care June : http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao- ca/files/Stroke_with_merged_supplement_sticker_2012.pdf Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ViaCs0k2jM Cognitive Behavioral Therapy - CBT A Framework to Support CBT for Emotional Disorder After Stroke* *Figure 2, Framework for CBT after stroke. -

Goal Setting Workbook

Workbook for Goal-setting and Evidence-based Strategies for Success Complete Workbook by Caroline Adams Miller, MAPP Author of Creating Your Best Life: The Ultimate Life List Guide Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 Theme One: Flourishing ................................................................................................. 6 Why Does Flourishing Matter? ................................................................................... 6 Success Flows from Happiness ................................................................................ 6 The Positivity Ratio .................................................................................................. 7 From the Source: Martin Seligman on Flourishing ................................................... 8 Jolts of Joy ................................................................................................................... 9 Happiness Boosters Worksheet ..............................................................................11 Introducing Character Strengths .............................................................................. 12 Exploring Your Own Character Strengths ............................................................. 13 Looking Back: Me at My Best ................................................................................ 14 Find Your Person-Activity Fit .................................................................................. -

Don't Make a Freudian Slip

PSYCHOLOGY DON’T MAKE A FREUDIAN SLIP Resources for Courses Activity Overview Outlining Freud’s Theory of Gender Development is a difficult task. Firstly, there are a lot of specialist terms that students often fail to include (e.g. unconscious processes, identification and internalisation) and secondly, it is very difficult to write a concise summary of Freud’s Theory because there is so much to include. The aim of this task is to consolidate student’s knowledge of the key Freudian terms and to practice writing a concise summary of Freud’s Theory of Gender Development. Resources Required . Don’t Make A Freudian Slip Handout Teacher Instructions Teaching & Learning Strategy A Provide the students with a copy of the Don’t Make A Freudian Slip Handout. Ask the students to read each paragraph in turn and add in the missing specialist terminology. After that, once you have gone through the answers, ask your students to highlight the specialist terminology related to Freud’s Theory of Gender Development. Once your students have completed the first task, ask them to write a concise summary of Freud’s Theory in approximately 125-175 words, while trying to incorporate all of the key features of Freud’s Theory. Tell the students to image that they are answering the following exam question: Describe and evaluate Freud’s psychoanalytic explanation of gender development. (16 marks) If you want to be cruel, only give your students six-eight minutes to complete their summary, as this is roughly the length of time they would have to write an outline in their exam. -

Benefits, Limitations, and Potential Harm in Psychodrama

Benefits, Limitations, and Potential Harm in Psychodrama (Training) © Copyright 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016 Rob Pramann, PhD, ABPP (Group Psychology) CCCU Training in Psychodrama, Sociometry, and Group Psychotherapy This article began in 2005 in response to a new question posed by the Utah chapter of NASW on their application for CEU endorsement. “If any speaker or session is presenting a fairly new, non-traditional or alternative approach, please describe the limitations, risks and/or benefits of the methods taught.” After documenting how Psychodrama is not a fairly new, non-traditional or alternative approach I wrote the following. I have made minor updates to it several times since. As a result of the encouragement, endorsement, and submission of it by a colleague it is listed in the online bibliography of psychodrama http://pdbib.org/. It is relevant to my approach to the education/training/supervision of Group Psychologists and the delivery of Group Psychology services. It is not a surprise that questions would be raised about the benefits, limitations, and potential harm of Psychodrama. J.L. Moreno (1989 – 1974) first conducted a psychodramatic session on April 1, 1921. It was but the next step in the evolution of his philosophical and theological interests. His approach continued to evolve during his lifetime. To him, creativity and (responsible) spontaneity were central. He never wrote a systematic overview of his approach and often mixed autobiographical and poetic material in with his discussion of his approach. He was a colorful figure and not afraid of controversy (Blatner, 2000). He was a prolific writer and seminal thinker. -

A Counter-Theory of Transference

A Counter-Theory of Transference John M. Shlien, Harvard University "Transference" is a fiction, invented and maintained by the therapist to protect himself from the consequences of his own behavior. To many, this assertion will seem an exaggeration, an outrage, an indictment. It is presented here as a serious hypothesis, charging a highly invested profession with the task of re-examining a fundamental concept in practice. It is not entirely new to consider transference as a defense. Even its proponents cast it among the defense mechanisms when they term it a "projection". But they mean that the defense is on the part of the patient. My assertion suggests a different type of defense; denial or distortion, and on the part of the therapist. Mine is not an official position in client-centered therapy. There is none. Carl Rogers has dealt with the subject succinctly, in about twenty pages (1951, pp. 198-217), a relatively brief treatment of a matter that has taken up volumes of the literature in the fleld.[1] "In client-centered therapy, this involved and persistent dependency relationship does not tend to develop" (p. 201), though such transference attitudes are evident in a considerable proportion of cases handled by client-centered therapists. Transference is not fostered or cultivated by this present-time oriented framework where intensive exploration of early childhood is not required, and where the therapist is visible and available for reality resting. While Rogers knows of the position taken here and has, I believe, been influenced by it since its first presentation in 1959, he has never treated the transference topic as an issue of dispute.