Out in the Cold: Science and the Environment in South Africa's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

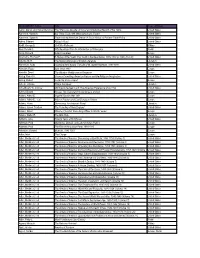

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert Bendiner The Strenuous Decade: A Social and Intellectual Record of the 1930s United States Aaronson, Susan A. Are There Trade-Offs When Americans Trade? United States Aaronson, Susan A. Trade and the American Dream: A Social History of Postwar Trade Policy United States Abbey, Edward Abbey's Road United States Abdill, George B. Civil War Railroads Military Abel, Donald C. Fifty Readings Plus: An Introduction to Philosophy World Abels, Richard Alfred The Great Europe Abernethy, Thomas P. A History of the South: The South in the New Nation, 1789-1819 (p.1996) (Vol. IV) United States Abrams, M. H. The Norton Anthology of English Literature Literature Abramson, Rudy Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986 United States Absalom, Roger Italy Since 1800 Europe Abulafia, David The Western Mediterranean Kingdoms Europe Abzug, Robert H. Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination United States Abzug, Robert Inside the Vicious Heart Europe Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart Literature Achenbaum, W. Andrew Old Age in the New Land: The American Experience since 1790 United States Acton, Edward Russia: The Tsarist and Soviet Legacy, 2nd ed. Europe Adams, Arthur E. Imperial Russia After 1861 Europe Adams, Arthur E., et al. Atlas of Russian and East European History Europe Adams, Henry Democracy: An American Novel Literature Adams, James Trustlow The Founding of New England United States Adams, Simon Winston Churchill: From Army Officer to World Leader Europe Adams, Walter R. The Blue Hole Literature Addams, Jane Twenty Years at Hull-House United States Adelman, Paul Gladstone, Disraeli, and Later Victorian Politics Europe Adelman, Paul The Rise of the Labour Party, 1880-1945 Europe Adenauer, Konrad Memoirs, 1945-1953 Europe Adkin, Mark The Charge Europe Adler, Mortimer J. -

The Joseph M. Bruccoli Great War Collection at the Unversity of South Carolina: an Illustrated Catalog Elizabeth Sudduth [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Rare Books & Special Collections Publications Collections 2005 The Joseph M. Bruccoli Great War Collection at the Unversity of South Carolina: An Illustrated Catalog Elizabeth Sudduth [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/rbsc_pubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Sudduth, Elizabeth, ed. The Joseph M. Bruccoli Great War Collection at the Unversity of South Carolina: An Illustrated Catalog. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 2005. http://www.sc.edu/uscpress/books/2005/3590.html © 2005 by University of South Carolina Used with permission of the University of South Carolina Press. This Book is brought to you by the Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rare Books & Special Collections Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOSEPH M. BRUCCOLI GREAT WAR COLLECTION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA Joseph M. Bruccoli in France, 1918 Joseph M. Bruccoli JMB great war collection University of South Carolina THE JOSEPH M. BRUCCOLI GREAT WAR COLLECTION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA AN ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE Compiled by Elizabeth Sudduth Introduction by Matthew J. Bruccoli Published in Cooperation with the Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA PRESS © 2005 University of South Carolina Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Joseph M. -

Sickness in Samuel Beckett's Fiction Jean

The Literature of Dissolution: Sickness in Samuel Beckett's Fiction ty Jean Schultz Herbert Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Bedford College, University of London, I9SI Supervised by Dr. Richard Cave ProQuest Number: 10098439 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10098439 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Beckett's art is predicated on his understanding and use of sickness in both its literal and figurative forms. In this thesis I deal critically with all of Beckett's major fiction, as well as with several lesser-known works. In the first chapter I cite evidence of Beckett's early preoccupation with physical illness and suggest a correlation between this preoccupation and his use of religious language and imagery. In Chapter Two I discuss the major women characters, who are portrayed as healthy and robust and are contrasted with the moribund heroes. In the next chapters, on Murphy and Watt, the subject of mental illness is examined. In these and the later chapters, Beckett's sense of play and his use of humour are explored within the context of the theme of sickness and dissolution. -

A Pair of Blue Eyes by Thomas Hardy

A Pair of Blue Eyes by Thomas Hardy 'A violet in the youth of primy nature, Forward, not permanent, sweet not lasting, The perfume and suppliance of a minute; No more.' PREFACE The following chapters were written at a time when the craze for indiscriminate church-restoration had just reached the remotest nooks of western England, where the wild and tragic features of the coast had long combined in perfect harmony with the crude Gothic Art of the ecclesiastical buildings scattered along it, throwing into extraordinary discord all architectural attempts at newness there. To restore the grey carcases of a mediaevalism whose spirit had fled, seemed a not less incongruous act than to set about renovating the adjoining crags themselves. Hence it happened that an imaginary history of three human hearts, whose emotions were not without correspondence with these material circumstances, found in the ordinary incidents of such church- renovations a fitting frame for its presentation. The shore and country about 'Castle Boterel' is now getting well known, and will be readily recognized. The spot is, I may add, the furthest westward of all those convenient corners wherein I have ventured to erect my theatre for these imperfect little dramas of country life and passions; and it lies near to, or no great way beyond, the vague border of the Wessex kingdom on that side, which, like the westering verge of modern American settlements, was progressive and uncertain. This, however, is of little importance. The place is pre- eminently (for one person at least) the region of dream and mystery. -

Screening Race in American Nontheatrical Film with a FOREWORD by JACQUELINE NAJUMA STEWART Screening Race in American Nontheatrical

Screening Race in American Nontheatrical Film WITH A FOREWORD BY JACQUELINE NAJUMA STEWART Screening Race in American Nontheatrical Film ALLYSON NADIA FIELD MARSHA GORDON EDITORS Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press Cover art: (Clockwise from All rights reserved top left) Untitled (Hayes Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on family, 1956–62), courtesy acid- free paper ∞ of the Wolfson Archives at Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Miami Dade College; Day Typeset in Minion Pro, Clarendon, and Din by of the Dead (Charles and Westchester Publishing Ser vices Ray Eames, 1957); Easter 55 Xmas Party (1955), courtesy Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data of the University of Names: Field, Allyson Nadia, [date] editor. | Gordon, Chicago/Ghian Foreman; Marsha, [date] editor. | Stewart, Jacqueline Najuma, [date] Gee family home film, writer of the foreword. courtesy of Brian Gee and Title: Screening race in American nontheatrical film / Center for Asian American edited by Allyson Nadia Field and Marsha Gordon ; Media; The Challenge with a foreword by Jacqueline Najuma Stewart. (Claude V. Bache, 1957). Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2019006361 (print) lccn 2019012085 (ebook) isbn 9781478005605 (ebook) isbn 9781478004141 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478004769 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Race in motion pictures. | Race awareness in motion pictures. | African Americans in motion pictures. | Minorities in motion pictures. | Motion pictures in education— United States. | Ethnographic films— United States. | Amateur films— United States. Classification: lcc pn1995.9.r22 (ebook) | lcc pn1995.9.r22 s374 2019 (print) | ddc 791.43/65529— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn .