Poetry and the Plural Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Billy Currington Bio Enjoy Yourself

BILLY CURRINGTON BIO ENJOY YOURSELF The title of Billy Currington’s new album, Enjoy Yourself, says it all. “That’s what I want people to think about doing when they hear my music,” the happy-go-lucky Georgia native says. “I want them to have a good time.” And a good time is clearly what they’re having. He’s garnered an impressive ten Top 10 hits, with six of those hitting No. 1 – “Pretty Good At Drinkin’ Beer,” “That’s How Country Boys Roll,” “People Are Crazy,” ”Don’t,” “Must Be Doin’ Somethin’ Right” and “Good Directions.” He’s sold millions of albums and has been selected to tour with the likes of Kenny Chesney, Brad Paisley and Sugarland. Tour mate Carrie Underwood notes that Billy’s “talent and charm” have made crowds fall in love with him. He also received the compliment of a lifetime from David Letterman, who said about Billy’s “People Are Crazy” performance, “This song will change your life. You’re not going to do any better than this song here.” His multiple nominations include two 2010 Grammy nominations (Male Country Vocal Performance and Best Country Song) for “People Are Crazy,” which also received nominations for Single and Song of the Year from the Academy of Country Music, as well as Single, Song and Video of the Year from the Country Music Association. He was honored with a 2006 nomination for Top New Male Vocalist at the ACMS, which followed 2005 ACM and CMA nominations for “Party For Two,” his duet with Shania Twain. -

Crazy People

CRAZY PEOPLE Chorégraphe : Adolfo CALDERERO, (10/2013) Description : Danse en ligne, 32 comptes, 4 murs, 1 Restart Niveau : Novice Musique : People are crazy - Billy CURRINGTON - 142 BPM 142 Départ : Intro 32 comptes SECTION 1 1-8: WEAVE RIGHT, TOUCH TOE RIGHT, SCUFF, CROSS, HOLD 1 – 4 Weave à D : PD à D - Cross PG derrière PD - PD à D – Cross PG devant PD [12:00] 5 Pointe PD derrière en diagonale à D 6 Scuff PD à côté du PG 7 Cross PD devant PG 8 Hold SECTION 2 9-16: WEAVE LEFT, TOUCH TOE LEFT, SCUFF, CROSS, HOLD 1 – 4 Weave à G : PG à G - Cross PD derrière PG - PG à G – Cross PD devant PG 5 Pointe PG derrière en diagonale à G 6 Scuff PG à côté du PD 7 Cross PG devant PD 8 Hold SECTION 3 17-24: STEP LOCK STEP BACK, KICK, TOGETHER, STOMP, KICK BALL CROSS 1 – 3 Step Lock Step Back : PD derrière, Verrouiller PG devant PD, PD derrière 4 Kick PG devant 5 Poser PG à côté du PD * Restart ici au 9ème mur 6 Stomp Up PD à côté du PG 7 & 8 Kick Ball Cross D : PD devant, Poser PD à côté du PG, cross PG devant PD SECTION 4 25-32: STEP SIDE, TOUCH TOE SIDE, HEEL STRUT ¼ TURN, FULL TURN, STOMPS 1 PD à D 2 Pointe PG à G (Genou à l'intérieur) 3 ¼ de tour à G et talon PG devant [9:00] 4 Poser PG au sol 5 ½ tour à G et PD derrière [3:00] 6 ½ tour à G et PG devant [9:00] 7 Stomp PD à côté du PG 8 Stomp PG à côté du PD *RESTART : Au 9ème mur, danser jusqu'au 5ème compte de la 3ème section, la musique s’arrête, puis attendre que la musique recommence pour reprendre la danse au début. -

Gender Stability and Change: the Differential Characterization of Men and Women in Popular Country Music from 1944 Through 2012

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2015 Gender Stability and Change: The Differential Characterization of Men and Women in Popular Country Music from 1944 through 2012 Clayton Cory Lowe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Lowe, Clayton Cory, "Gender Stability and Change: The Differential Characterization of Men and Women in Popular Country Music from 1944 through 2012" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1299. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1299 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER STABILITY AND CHANGE: THE DIFFERENTIAL CHARACTERIZATION OF MEN AND WOMEN IN POPULAR COUNTRY MUSIC FROM 1944 THROUGH 2012 by C. Cory Lowe (Under the Direction of Nancy L. Malcom) ABSTRACT This research is a longitudinal study of differential depictions of men and women in top country music from 1944 through 2012. The study attempts to understand the gender system as theorized by Ridgeway using the analytic heuristics of cognitive sociologists and the methods of ethnographic content analysts. Findings include the various axes upon which women and men are differentially characterized over time including men and women's behaviors within romantic relationships, involvement in deviance and crime, work and the use of economic capital, their bodies, and differences in cultural capital such as education. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Atlantic Crossing

Artists like WARRENAI Tour Hard And Push Tap Could The Jam Band M Help Save The Music? ATLANTIC CROSSING 1/0000 ZOV£-10806 V3 Ii3V39 9N01 MIKA INVADES 3AV W13 OVa a STOO AlN33219 AINOW AMERICA IIII""1111"111111""111"1"11"11"1"Illii"P"II"1111 00/000 tOV loo OPIVW#6/23/00NE6TON 00 11910-E N3S,,*.***************...*. 3310NX0A .4 www.americanradiohistory.com "No, seriously, I'm at First Entertainment. Yeah, I know it's Saturday:" So there I was - 9:20 am, relaxing on the patio, enjoying the free gourmet coffee, being way too productive via the free WiFi, when it dawned on me ... I'm at my credit union. AND, it's Saturday morning! First Entertainment Credit Union is proud to announce the opening of our newest branch located at 4067 Laurel Canyon Blvd. near Ventura Blvd. in Studio City. Our members are all folks just like you - entertainment industry people with, you know... important stuff to do. Stop by soon - the java's on us, the patio is always open, and full - service banking convenience surrounds you. We now have 9 convenient locations in the Greater LA area to serve you. All branches are FIRSTENTERTAINMENT ¡_ CREDITUNION open Monday - Thursday 8:30 am to 5:00 pm and An Alternative Way to Bank k Friday 8:30 am to 6:00 pm and online 24/7. Plus, our Studio City Branch is also open on Saturday Everyone welcome! 9:00 am to 2:00 pm. We hope to see you soon. If you're reading this ad, you're eligible to join. -

Take Your Songwriting to the Next Level by Adding a Twist

Take Your Songwriting to the Next Level by Adding a Twist From surprise endings to modulations and double entendre, songs with twists can really pay-off. Posted in MusicWorld on October 14, 2016 by Jason Blume To grab our listeners’ attention we need to separate our songs from the competition, and one way to accomplish this is by including an unexpected twist—an element of surprise. This article examines various ways to incorporate twists into lyrics and melodies. Story Songs With Surprise Endings “Ol’ Red” (written by James Bohan, Don Goodman, and Mark Sherrill, and recorded by George Jones, Kenny Rogers, and Blake Shelton) is an exceptional example of a story song with a lyric that ends with a powerful punch. The lyric tells the story of a prisoner who, while serving a 99- year sentence for a crime of passion, takes care of a bloodhound named Ol’ Red. The narrator devises a plan to escape from prison that starts with having someone hide a female blue tick hound where the prisoner walks Ol’ Red each evening. After the bloodhound has grown to expect those nightly conjugal visits, the prisoner keeps the dogs apart for several days. The prisoner makes his escape, confident that Ol’ Red will lead the prison guards to his blue tick girlfriend—and not to the fugitive. For an added payoff, the song ends with the narrator saying that now, there are red-haired blue ticks all over the south, and that just as love got him into prison, love got him out. Watch Blake Shelton’s video here. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS AUGUST 5, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Luke Combs’ Songwriter Ashley Gorley Advances From New Chart Marks >page 4 The Tape Room To The Executive Lounge Cash’s Kitchen Opens When Valory released the self-titled debut EP by new female act have a place in the music business or not, there was always some >page 10 Avenue Beat on July 26, it was perhaps a career-defining moment writing, some production, some publishing, some mentoring and for the Illinois-bred trio, but it also represents a new track for the some working with artists and labels and stuff like that. So it was Kentucky-born executive behind the band. just more of a matter of the order where I felt like I could commit.” Avenue Beat marks the first joint venture label deal for Gorley, who is actually a staff writer for Round Hill Music, isn’t Opry Names Tape Room, a publishing company founded by ace songwriter the only songwriter who has parlayed musical success into some New Leader Ashley Gorley (“Dirt on My Boots,” “Liv- form of a Nashville empire, but his mix of cre- >page 10 ing”) in 2011. If this expansion into new ative savvy and business acumen is a rare territory follows suit with Gorley’s history, combination among the genre’s composers. it would be the beginning of something big. “He’d probably be in Silicon Valley Gorley has piled up 34 No. 1country singles creating a new start-up right now if he weren’t Rhett And Brett: in Billboard as a songwriter, stretching from a songwriter,” says writer-producer Ross Fashion On Display Trace Adkins’ 2007 single “You’re Gonna Copperman (“I Lived It,” “Get Along”). -

Nashvillemusicguide.Com 1 CD, DVD, & Tape Duplication, Replication, Printing, Packaging, Graphic Design, and Audio/Video Conversions

NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 CD, DVD, & Tape Duplication, Replication, Printing, Packaging, Graphic Design, and Audio/Video Conversions we make it easy! Great prices Terrific turnaround time Hassle - free, first - class personal service Jewel case package prices just got even better! 500 CD Package starts at $525 5-6 business days turnaround 300 CD Package starts at $360 4-5 business days turnaround 100 CD Package starts at $170 3-4 business days turnaround. Or check out our duplication deals on custom printed sleeve, digipaks, wallets, and other CD/DVD packages Call or email today to get your project moving! 615.244.4236 [email protected] or visit wemaketapes.com for a custom quote On Nashville’s Historic Music Row For 33 Years 118 16th Avenue South - Suite 1 Nashville, TN 37203 (Located just behind Off-Broadway Shoes) Toll Free: 888.868.8852 Fax: 615.256.4423 Become our fan on and follow us on to receive special offers! NashvilleMusicGuide.com 2 NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 Executive Editor & CEO Randy Mat- Contents Letter from the Editor thews 34 [email protected] Let's start out by letting everyone on these pages and they will be jamming with us on May Features know that Big Joe Matthews has left 17th for our Blues Jam at Winner's. Be sure to come out Managing Editor Amanda Andrews the building. We would like to sin- to the kick-off our first Special Edition at our Blues Jam. [email protected] cerely thank him for all his hard work We will have a series of Special Editions throughout the 7 Music City Smokehouse at NMG. -

Bobby Braddock: a Lifetime of Hitmaking

Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum • Words & Music • Grades 7-12 Bobby Braddock: A Lifetime of Hitmaking Songwriters have to keep up with changing musical tastes if they want to have long careers. No one has done that better than Bobby Braddock. The Country Music Hall of Fame member has had #1 country songs in five consecutive decades. Looking back at the string of hits that Braddock registered from the 1960s to the early 1980s, music historian and Braddock friend Michael Kosser describes Bobby as “absolutely fearless.” Kosser writes, “His best was among the best there ever was, his mediocre was often good enough for radio success, and his worst . well, that’s the price of being fearless in creativity.” Braddock was born August 5, 1940, in Lakeland, Florida. ballads. His most famous in the latter category is “He Stopped He grew up in nearby Auburndale. He started taking piano Loving Her Today.” Co-written with Curly Putman and lessons at age seven and spent “six years of little old ladies released in 1980 by George Jones, it is considered by many to trying to teach me to read music,” but he eventually discovered be the greatest country song of all time. “I could learn more piano listening carefully to our records Braddock hit a slump in the mid-1980s, when, he admits, than from the conventional, by-the-book music teachers.” “I was doing some of my best writing, but it was not The boy’s musical interests ranged from bluegrass to necessarily compatible with country radio at that time.” barbershop quartets, but he became increasingly captivated By the mid-1990s, he was back on the charts with a whole by the evolving sounds of country and rock & roll. -

Serendipity Karaoke

Serendipity Karaoke .38 Special Abba (cont.) Adele (cont.) Hold On Loosely Mamma Mia Rolling In The Deep 2 Pac Ft. Elton John Accept Rumour Has It Ghetto Gospel Balls To The Wall Send My Love (To Your New 23 (Explicit) Acdc Lover) Mike Will Made-It (Feat. Miley Back In Black Set Fire To The Rain Cyrus, Ju Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap Skyfall 3 Doors Down For Those About To Rock Someone Like You Let Me Be Myself Hell's Bells Turning Tables 3 Doors Down Highway To Hell Water Under The Bridge Away From The Sun Moneytalks When We Were Young Be Like That Play Ball Adkins, Trace Here By Me Stiff Upper Lip Ala-Freakin-Bama Kryptonite Thunderstruck Brown Chicken Brown Cow Let Me Go Tnt Every Light In The House Is On Live For Today Whole Lotta Rosie Honky Tonk Badonkadonk Road I'm On, The You Shook Me All Night Long I Got My Game On When I'm Gone Ace of Base I Left Something Turned On At When You're Young All That She Wants Home 38 Special Sign, The One Hot Mama If I'd Been The One Ad Libs, The You're Gonna Miss This Second Chance Boy From New York City, The Aerosmith 3Lw Adam and The Ants Angel No More Stand and Deliver Dream On No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Stand and Deliver! Girls of Summer 5 Seconds of Summer Adams, Bryan I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Amnesia Best of Me, The Sunshine Don't Stop Cuts Like A Knife Walk This Way Kiss Me Kiss Me Everything I Do, I Do It For You Afroman She Looks So Perfect Have You Ever Really Loved A Because I Got High She's Kinda Hot Woman Aguilera, Christina 50 Cent Here I Am Ain't No Other Man Disco Inferno Run -

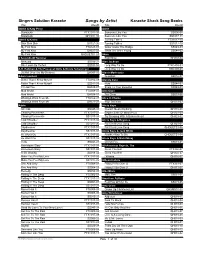

Singers Solution Karaoke Song Book Also Fasttrax and Quik Hitz

Singers Solution Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Adele Starstrukk FTX1011-10 Someone Like You SS006-08 Starstrukk QH1011-10 Someone Like You SS1017-11 3OH!3 & Kesha Turning Tables FTX1017-10 Blah Blah Blah QH321-06 Turning Tables SS1017-10 My First Kiss FTX327-03 Water Under The Bridge SS049-09 My First Kiss QH327-03 When We Were Young SS044-02 My First Kiss QHDUETS1-03 Akon 5 Seconds Of Summer Right Now QH303-04 Amnesia SS036-07 Alan Jackson She Looks So Perfect SS032-04 Long Way To Go FTXC409-03 A.R. Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls & Nicole Scherzinger Long Way To Go SSC409-03 Jai Ho! (You Are My Destiny) QH307-05 Alanis Morissette Adam Lambert Guardian SS016-07 Better Than I Know Myself FTX012-09 Alessia Cara Better Than I Know Myself SS012-09 Here SS044-03 If I Had You QH325-07 Scars To Your Beautiful SS049-03 Mad World FTX308-07 Alex Clare Mad World QH308-07 Too Close SS019-06 Whataya Want From Me FTX322-07 Alice In Chains Whataya Want From Me QH322-07 Your Decision QH323-03 Adele Alicia Keys All I Ask SS045-01 Doesn't Mean Anything QH316-08 Chasing Pavements FTX1017-04 Empire State Of Mind (Pt 2) QH321-09 Chasing Pavements SS1017-04 Try Sleeping With A Broken Heart QH323-02 Cold Shoulder FTX1017-06 Alicia Keys & Beyonce Cold Shoulder SS1017-06 Put It In A Love Song QH321-01 Daydreamer FTX1017-07 Put It In A Love Song QHDUETS1-06 Daydreamer SS1017-07 Alicia Keys & Jack White He Won't Go FTX1017-02 Another Way To Die QHDUETS1-04 He Won't Go SS1017-02 Alicia Keys & Nicki Minaj -

Braddock Is Good Poet/Scribe Writes on by David M

page 1 Wednesday, June 3, 2009 People Are Crazy; Braddock Is Good Poet/Scribe Writes On by David M. Ross Bobby Braddock? His "A lot of times when pen etches comedic lines people cowrite, one will like "Well, I bass quit sea often write more than horsing around or you folks the other," says Braddock. will go into a state of shark!" "But this was very co- and co-writes a serious written, right down the country classic such as "He middle with each of us Stopped Loving Her Today." pulling our weight. I had Quirky might be a good never met Troy, but we place to start, followed by hit it off real well cause talented, innovative and we both are originally compelling. Braddock's from small Florida towns. induction into the prestigious He was nice enough to Nashville Songwriters Hall Bobby Braddock invite me to write this. I of Fame is proof that Music want to be clear—'People City's songwriter community also Are Crazy' was his idea. I could have gone embraces those adjectives to describe a million years and never thought of 'God this writer's work. Over a career spanning is Great, Beer is Good, and People are 40+ years he has achieved 13 No. 1 Crazy.' Troy is a very clever fellow, he also singles. wrote Kenny Chesney's 'Shiftwork.' Last week I heard the lines, What brings 'People…' is so quirky that two or three you to Ohio? He said "Damned if I know" people said, 'That's Braddock all over it,' followed by the chorus God is great, Beer but I said 'No, my co-writer is pretty quirky is good and People are crazy.