Women and Sport: a Summary of Potential Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 6: Our Sporting Stars

Key Stage 2: Learning about Northern Ireland, 1921–2021 6 LESSON 6: OUR SPORTING STARS Activity 1: What Does it Take? (15 minutes) Activity 2: Dame Mary Peters (30 minutes) Activity 3: Our Sporting Heroes and Heroines (30 minutes) Activity 4: Project (50 minutes) INTRODUCTION This lesson focuses on Northern Ireland’s sporting champions. It encourages the children to consider the skills and qualities needed to make it to the top and the highs and lows of the journey to get there. Through active learning strategies, the children learn about the achievements of some of Northern Ireland’s sporting stars. In the final activity they have the opportunity to focus on a sporting champion of their choice. You can use this lesson as a stand-alone resource or as an extended piece of work. Alternatively, adapt individual activities to link with other themes or topics and ability levels. LEARNING INTENTIONS RESOURCES KEY WORDS The children will: • Resource 1: What qualities Hero, heroine, • consider the qualities it takes to would it take to become a legacy, qualities, succeed in the sporting field; sports star? personality, • become familiar with Dame • Resource 2: What would it successful, Mary Peters – her life and her be like to be a professional champion, legacy; sportsperson? biography, • be aware of the range of • Resource 3: Dame Mary compete, sporting heroes and heroines Peters challenge, we have in Northern Ireland; • Resource 4: Fact Files achievement • have a knowledge of some of • Resource 5: Our Sporting sports stars in Northern Ireland Stars Presentation and their contribution to the world stage; and • carry out research on a sporting star. -

Download 30 May Agenda

ARDS AND NORTH DOWN BOROUGH COUNCIL 25 May 2018 Dear Sir/Madam You are hereby invited to attend a meeting of the Ards and North Down Borough Council which will be held in the Council Chamber, Town Hall, The Castle, Bangor on Wednesday, 30 May 2018 commencing at 7.00pm. Yours faithfully Stephen Reid Chief Executive Ards and North Down Borough Council A G E N D A 1. Prayer 2. Apologies 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Mayor’s Business 4.1 Presentation of Elected Member Development Charter 5. Mayor and Deputy Mayor Engagements for the Month (To be tabled) 6. Minutes of Meeting of Council dated 25 April 2018 (Copy attached) 7. Minutes of Committees (Copies attached) 7.1 Planning Committee dated 1 May 2018 7.2 Environment Committee dated 2 May 2018 7.3 Regeneration and Development Committee dated 3 May 2018 7.4 Corporate Services Committee dated 8 May 2018 7.5 Community and Wellbeing Committee dated 9 May 2018 8. Requests for Deputations 8.1 Translink – Transport Plans for the Borough (Copy email attached) 8.2 Caring Communities Safe and Well – Local services for older people (Copy email attached) 9. Consultation Documents 9.1 Consultation on proposed Marine Plan for Northern Ireland (Report attached) 10. Conferences, Invitations etc. 10.1 Invitation - 21st Columban's Day, Friends of Columbanus, Brittany (Report attached) 10.2. Service of Commemoration – Portadown (Correspondence attached) 10.3. 2018 NILGA Conference and Gala Awards – 11 October 2018 (Correspondence attached) 10.4. NILGA - Community Planning and Wellbeing Network Event – 21 June 2018 – Seagoe Hotel, Craigavon (Correspondence attached) 10.5. -

The Annual Report and Accounts 2019 2 British Swimming Annual Report and Accounts 2019 British Swimming Annual Report | Company Information 3

The Annual Report and accounts 2019 2 British Swimming Annual Report and Accounts 2019 British Swimming Annual Report | Company Information 3 Company Contents Information For the year ended 31 March 2018 03 company Information CHAIRMAN REGISTERED OFFICE 04 Chairman’s Report Edward Maurice Watkins CBE British Swimming Pavilion 3 05 CEO’S report DIRECTORS Sportpark 06 Monthly Highlights 3 Oakwood Drive Keith David Ashton Loughborough 08 World Championships Jack Richard Buckner LE11 3QF 10 World Para Swimming Championships David Robert Carry Bankers 11 Excellence - Swimming Urvashi Dilip Dattani Lloyds Bank 15 Excellence - Diving Graham Ian Edmunds 37/38 High Street 19 Excellence - para-Swimming Loughborough Jane Nickerson Leicestershire 22 NON Funded sports update Fergus Gerard Feeney LE11 2QG 23 Corporate UPDATE Alexandra Joanna Kelham Coutts & Co. 24 International relations 440 Strand Peter Jeremy Littlewood London 26 governance Statement Graeme Robertson Marchbank WC2R 0QS 28 Major events Adele Stach-Kevitz AUDITOR 30 Marketing and communications COMPANY SECRETARY Mazars LLP 31 finances ParkView House 38 Acknowledgements Ashley Cox 58 The Ropewalk Nottingham COMPANY REGISTRATION NUMBER NG15DW 4092510 Front Cover Images: FINA Champions Swim Series 2019 – Imogen Clark. FINA World Championships 2019 – Thomas Daley. World Para-swimming Allianz Championships 2019 – Tully Kearney. 4 British Swimming Annual Report and Accounts 2019 British Swimming Annual Report | CEO's Report 5 Chairman’s CEO's Report Report edward MAURICE WATKINS CBE Jack Richard Buckner This was yet another noteworthy year for British Swimming with was clarified since when British Athletes have been involved in There was a time when the year before the Olympic and We are now moving forward with a focus on the Tokyo Olympics the 18th FINA World Aquatic Championships in Gwangju South both the inaugural FINA Champions Series and will be available Paralympic games was a slightly quieter year in the hectic world and Paralympics. -

The Village Voice

Nov 2 The Village 016 Voice Issue 91 Taken on 23rd October 2013 In this issue News from Lesley McNeill Page 2 Auchlochan Men’s Social Group Page 8 News from Will Clifford Page 2 News from A.C.E. Page 9 News from Sales Team Page 3 Film Afternoon Page 9 News from David McGrane Page 3 The Notice Board Page 10-22 News from Customer Services Page 4 News from Homecare Page 4 News from Lower Johnshill Page 6 Auchlochan Studios Page 6 Chaplaincy Chatter Page 7 Page | 1 News from News from Lesley McNeill Will Clifford I quite like watching “Homes Under the Now the clocks have turned back we will see Hammer” and I’m constantly amazed when I brighter mornings and darker afternoons and it hear buyer’s vision for their run down bargains. won’t be long until we hear the Christmas I don’t think Nethanvale could ever have been music playing in the shops. considered in those terms when it was a care home but it’s pleasing to hear so many people As always we welcome all new residents to the say how impressed they are with its village and hope you enjoy village life with us. transformation. Our thoughts and prayers are with those residents who are unwell or have been in I think it’s testament to the vision of the people hospital over the past month. who laid the foundations of this wonderful village, that MHA have been able to create Our thoughts are with the family of Mr Jeff these stunning flats. -

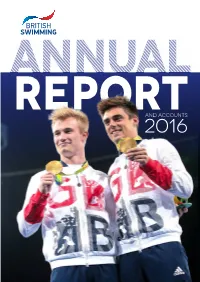

Reportand Accounts 2016 02 ANNUAL REPORT and ACCOUNTS 2016 CONTENTS 03

annual reportand accounts 2016 02 ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2016 CONTENTS 03 Left: Olivia Federici and Katie Clark compete in the Duet Free prelims INTERNATIONAL at the Rio Olympics 2016. Cover: Jack Laugher and Chris Mears with their gold medals at the Rio Olympics 2016. Alex Whitehead/SWpix.com EXCELLENCE CONTENTS 04 COMPANY INFORMATION 06 Chairman’s Report Maurice Watkins 07 Chief Executive’s Report David Sparkes 08 Olympic Games Rio 2106 22 Paralympic Games Rio 2016 30 LEN EUROPEAN championships 2016 40 IPC EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS 2016 STATEMENTS FINANCIAL 42 EUROPEAN junior championships 2016 46 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 50 CORPORATE 52 EXCELLENCE 72 major events strategy 2017-2024 74 Financial Statements 82 Acknowledgements ONLINE ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS https://www.britishswimming.org/about-us/annual-reports 04 ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2016 COMPANY INFORMATION 05 COMPANY Great Britain’s Laura Stephens INTERNATIONAL competes in the Women’s 50m Butterfly heats at the 2016 LEN European Aquatics Championships, INFORMATION London Aquatics Centre. Alex Whitehead/SWpix.com For the year ended 31 March 2016 CHAIRMAN BANKERS Edward Maurice Watkins CBE Lloyds Bank 37/38 High Street Loughborough DIRECTORS Leicestershire Maureen Campbell LE11 2QG Urvashi Dattani (appointed 1 Jan 2016) Graham Edmunds Kleinwort Benson William Raymond Gordon 14 St.George Street John Craig Hunter London EXCELLENCE Robert Michael Kenneth John James W1S 1FE Alexandra Joanna Kelham Peter Jeremy Littlewood Coutts & Co. Michael John Power (retired 31 December 2015) -

Irish Team Media Guide Rio Paralympic Games

IRISH TEAM MEDIA GUIDE RIO PARALYMPIC GAMES #MORETHANSPORT 2016 PAGE // 2 IRISH TEAM MEDIA GUIDE 2016 IRISH TEAM MEDIA GUIDE RIO PARALYMPIC GAMES Table of Contents The Road to Rio // 04 Paralympics Explained // 06 Irish Paralympic History // 08 What’s new for Rio 2016 // 10 Where to go -Paralympic Venues //12 Irish team fast facts // 14 Meet the Chef -Denis Toomy //16 Meet Team Ireland // 18 Paralympics Ireland Media Services // 64 Brazilian words and phrases // 66 Tweet tweet // 70 Glossary Of terms // 71 Competition Schedule // 72 THE ROAD TO RIO PAGE // 4 IRISH TEAM MEDIA GUIDE 2016 s the Irish Team marches into the Maracana the necessary support in order to ensure optimum A Stadium for the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games performance at the Games. Working from a qua- Opening Ceremony on September 7th, it will be the drennial Performance Plan which was laid down in final step of a long and hard-fought journey. For the the aftermath of London 2012, Toomey and Malone 46 Irish athletes, this journey hasn’t always been an have worked hand in hand to support the staff and easy one. It has been one that has been filled with sports science and medical team to help these ath- highs and lows, ups and downs, disappointments letes reach key performance. and successes, but inevitably, one that has brought As a result, 2015 was a key year in the calen- them to the pinnacle of their sporting career and dar for Irish athletes, with World Championships now sees them on the greatest of all sporting stages. -

Minutes of Active Belfast Limited Board 16.01.17 PDF 195 KB

ACTIVE BELFAST LIMITED BOARD Monday, 16th January, 2017 MEETING OF ACTIVE BELFAST LIMITED BOARD (Held in the Lavery Room, City Hall) Attendees Directors: Mr. J. McGuigan (Chairperson) Councillor Boyle Councillor Corr Mr. P. Boyle Mr. J. Higgins Ms. K. McCullough Mr. M. McGarrity Mr. N. Mitchell Mr. K. O’Doherty Mr. R. Stewart Mr. G. Walls and Mr. C. Webster. Officers: Mrs. R. Crozier, Assistant Director City and Neighbourhood Services; Mr. N. Munnis, Partnership Manager; and Mr. H. Downey, Democratic Services Officer. GLL: Mr. G. Kirk, Regional Director and Mr. G. Holland, Partnership Manager. Welcome The Chairperson welcomed Councillor Corr, who had replaced Councillor McAteer, and Mr. O’Doherty, the Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance’s representative, to their first meeting. Apologies Apologies were reported on behalf of Councillor Long and Mr. Kirkwood. Minutes The minutes of the meeting of 5th December were approved. Matters Arising Hire Charges for Council Pitches The Assistant Director informed the Board that the People and Communities Committee, at its meeting on 6th December, had recommended that the cost of hire of the Council’s 3G pitches should be reduced by 25%. The Committee had agreed also that its 1 proposal should be brought to the attention of the Strategic Policy and Resources Committee for a decision, given its potential impact upon the overall rate setting process. She reported that the Strategic Policy and Resources Committee was due to discuss the implications of the proposed reduction at its meeting on 20th January, as part of its overall consideration of the Revenue Estimates and District Rate for 2017/2018 and that the Board would, in due course, be advised of the outcome of that meeting. -

INAS Global Games Queensland Sport & Athletics Centre - Site License QSAC - SAF - 14/10/2019 to 18/10/2019 Results

FULL RESULTS Contents Athletics Page 3 Basketball Page 28 Cricket Page 30 Cycling Page 31 Futsal Page 37 Rowing Page 41 Swimming Page 51 Table Tennis Page 124 Taekwondo Page 185 Tennis Page 202 Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 4:04 PM 23/10/2019 Page 1 2019 INAS Global Games Queensland Sport & Athletics Centre - Site License QSAC - SAF - 14/10/2019 to 18/10/2019 Results Women 100 Metre T20 II-1 ================================================================ Name Year Team Heats ================================================================ Heat 1 Heats Wind: -4.9 1 Kimura T20, Mayaka 88 Japan 13.34Q 2 Adama T20, Nawa 99 France 13.38Q 3 da Silva, Jardenia 03 Brazil 13.62Q 4 Santos T20, Claudia 89 Portugal 13.93q 5 Garcia, Deyanira 95 Spain 14.18 6 Skuhrovska T20, Veronika 95 Czech Republic 14.66 7 Beilby, Brittney 00 Australia 15.65 Heat 2 Heats Wind: 0.8 DQ WPA 17.8 1 Delage, Danielle 92 France 13.26Q 2 Padilla Lara T20, Marlix 98 Ecuador 13.30Q 3 Charuswat, Sukanya 99 Thailand 13.35Q 4 Titerova, Tereza 97 Czech Republic 13.49q 5 Gago, Ohiane 95 Spain 14.09 6 Mazzei T20, Amelia 02 Australia 14.29 -- Suzuki T20, Yuki 94 Japan Women 100 Metre T20 II-1 ================================================================ Name Year Team Finals ================================================================ Heat 1 Finals Wind: 1.8 1 Adama T20, Nawa 99 France 13.17 2 Charuswat, Sukanya 99 Thailand 13.22 3 da Silva, Jardenia 03 Brazil 13.25 4 Kimura T20, Mayaka 88 Japan 13.30 5 Padilla Lara T20, Marlix 98 Ecuador 13.34 6 Delage, Danielle 92 France 13.45 -

EMPOWERED More Female Para Athletes Are Rising up to Challenges

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE PARALYMPIC MOVEMENT ISSUE # 01 | 2019 THE EMPOWERED More female Para athletes are rising up to challenges DIGITAL DYNAMICS CASE STUDY FEATURE Paralympic Movement celebrates Marketing secrets of a successful How one woman’s story won women’s achievements wheelchair basketball Worlds the 2020 Paralympic bid PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE “The IPC has achieved a great deal in a relatively short space of time – probably far more than most could have imagined 30 years ago when the organisation was formed.” 48The USA’s Keith Gabel high fives kids who attended a Para snowboard camp held during the 2019 World Championships ear readers, membership-focussed and make for a more inclusive world through Para sport. With so As the IPC prepares to celebrate many opportunities out there, it is important its 30th anniversary this autumn, we maximise our potential, developing the the organisation is changing, gearing up for its Paralympic Movement at all levels in the further evolution. coming years. Since the last edition of The Paralympian, we This edition of The Paralympian underlines why have announced a change of leadership at the I am so excited for the future of the Paralympic head of the IPC management team, confirmed Movement. The last six months have been the IPC will move to bigger offices in our home jam-packed featuring great Para sport events city of Bonn, Germany, made strong progress with taekwondo and ice hockey leading the with the governance review and the IPC way with outstanding World Championships. Athletes’ Council published its first strategy. This summer promises to follow suit with no less than 12 World Championships ahead of Soon to follow will be the IPC Strategic Plan us. -

A Resource for Working with Young Women

HITTING THE MARK IN WORKING WITH YOUNG WOMEN >> Bullseye> > A resource for working with young women by YouthAction Northern Ireland Equality Work with Young Women 2021 HITTING THE MARK IN WORKING WITH YOUNG WOMEN 3 >>> Bullseye> What is this? This logo will appear throughout, Previous edition (2014): Youth Action Northern Ireland highlighting worksheets and other resources Latest edition (2021): Annette Feldmann and Dr. Martin McMullan. you might find useful to photocopy. With support from Roisin Kelly, Emma Johnston, Dearbhaila Flynn and Sarah McGennity. 4 HITTING THE MARK IN WORKING WITH YOUNG WOMEN >> Bullseye> >Contents Hear the voices of Quadrant 2 - About us 24 Quadrant 4 - About action 66 young women 5 A job for the boys 24 Creating your own youth campaign 66 Alternative alphabet 28 Message in a bottle 69 Building on history 7 Sugar and spice 30 Create a manifesto of key asks 69 Using this resource 8 Ken and Barbie 31 Pitch your idea 69 Double standards game 32 Preparing to protest 70 Don’t do drunk what you wouldn’t do sober 34 Getting started 9 Resources and links 71 Journey of life - gendered lens 37 Understanding sex, gender, stereotypes Sing us a song 38 Other YouthAction resources 72 and prejudice 9 Three of a kind 39 Preparation for the facilitator 10 What’s in a name? 41 The dartboard model 11 The flower and the football 42 Who does what? 43 Quadrant 1 - About me 13 Quadrant 3 - About women 45 Pizza slice worksheet 13 Contracting 15 Race of life 46 This is me... Facebook 15 Fix me, love me 48 Group juggle 15 Owning your body 51 Geeting to know you and me 16 Points of view 54 Lifemaps 17 The F word 55 Journey of life 22 Quiz 57 Journey of life (rocking chair) 22 Life swap worldwide 58 Many masks 23 A century of women 60 What has feminism ever done for you? 64 HITTING THE MARK IN WORKING WITH YOUNG WOMEN 5 HEAR THE VOICES OF YOUNG WOMEN Bullseye is a resource to support work with young women. -

The Paralympic Games on Seven

1 The Paralympic Games on Seven Unmissable on Seven and Connected Devices Foreword 3 How We Will Cover the Paralympic Games 4 From Saul Shtein 5 From Kerry Stokes 6 From Tim Worner 7 From Kurt Burnette 8 Seven is Ready for Rio 9 From the Australian Paralympic Committee 10 Seven’s Digital Coverage of the Paralympic Games 11 Seven’s Paralympic Games Commentary Team 13 The Paralympic Games – A History and Overview 18 The Paralympic Games in Rio 22 Australians to Watch in Rio 26 International Athletes to Watch in Rio 42 All times are AEST. Check Local Guides Day-by-day Guide to Seven’s Paralympic Games Coverage 56 2 Foreword In Rio, we will be part of a global television community that will capture dramatic vision of some of the most extraordinary moments in sports. We will be undertaking the most extensive coverage of a Paralympic Games ever – every key moment of the Paralympic Games will be delivered to all Australians across 7TWO and connected devices. The Paralympics Games are a commitment to excellence that invigorates us and we look forward to meeting the challenge of bringing one of the world’s biggest and most inspiring events to television and connected devices. Seven will produce more than 120 hours of live and highlights coverage as well as live Opening and Closing ceremony coverage. 200 people will be involved in the Australian television coverage with major production and transmission centres in Rio, Sydney and Melbourne creating Seven’s Paralympic Games coverage through live and exclusive coverage plus Sunrise, Seven News and The Morning Show and Daily Edition. -

Assembly Business Matter of the Day Michael Mckillop

Assembly Business Matter of the Day Michael McKillop ........................................................................................................................... 3 Assembly Business Committee Business Committee Membership ................................................................................................................ 8 Ministerial Statement British-Irish Council Misuse of Drugs Sectoral Format ................................................................... 9 North/South Ministerial Council: Aquaculture and Marine............................................................... 19 Draft Strategic Framework for Public Health 'Fit and Well - Changing Lives 2012 - 2022' ............... 22 Private Members' Business World Suicide Prevention Day ....................................................................................................... 31 Oral Answers to Questions Enterprise, Trade and Investment ................................................................................................. 33 Environment ................................................................................................................................. 39 World Suicide Prevention Day ....................................................................................................... 46 Question for Urgent Oral Answer Ralph's Close Care Home, Gransha .............................................................................................. 57 Private Members' Business VAT: Hospitality Sector ................................................................................................................