Patterns in the Maritime Co-Operative Movement 1900 -1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celtic-Colours-Guide-2019-1

11-19 October 2019 • Cape Breton Island Festival Guide e l ù t h a s a n ò l l g r a t e i i d i r h . a g L s i i s k l e i t a h h e t ò o e c b e , a n n i a t h h a m t o s d u o r e r s o u ’ a n d n s n a o u r r a t I l . s u y l c a g n r a d e h , n t c e , u l n l u t i f u e r h l e t i u h E o e y r r e h a t i i s w d h e e e d v i p l , a a v d i b n r a a t n h c a e t r i a u c ’ a a h t a n a u h c ’ a s i r h c a t l o C WELCOME Message from the Atlantic Canada Message de l’Agence de promotion A Message from the Honourable Opportunities Agency économique du Canada atlantique Stephen McNeil, M.L.A. Premier Welcome to the 2019 Celtic Colours Bienvenue au Celtic Colours On behalf of the Province of Nova International Festival International Festival 2019 Scotia, I am delighted to welcome you to the 2019 Celtic Colours International Tourism is a vital part of the Atlantic Le tourisme est une composante Festival. -

In This Document an Attempt Is Made to Present an Introduction to Adult Board. Reviews the Entire Field of Adult Education. Also

rn DOCUMENT RESUME ED 024 875 AC 002 984 By-Kidd. J. R., Ed Adult Education in Canada. Canadian Association for Adult Education, Toronto (Ontario). Pub Date SO Note- 262p. EDRS Price MF-$1.00 HC-$13.20 Descriptors- *Adult Education Programs. *Adult Leaders, Armed Forces, Bibliographies, BroadcastIndustry, Consumer Education, Educational Radio, Educational Trends, Libraries, ProfessionalAssociations, Program Descriptions, Public Schools. Rural Areas, Universities, Urban Areas Identifier s- *Canada Inthis document an attempt is made to present an introduction toadult education in Canada. The first section surveys the historical background, attemptsto show what have been the objectives of this field, and tries to assessits present position. Section IL which focuses on the relationship amongthe Canadian Association for Adult Education, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and theNational Film Board. reviews the entirefield of adult education. Also covered are university extension services. the People's Library of Nova Scotia,and the roles of schools and specialized organizations. Section III deals1 in some detail, with selected programs the 'Uncommon Schools' which include Frontier College, and BanffSchool of Fine Arts, and the School .of Community Programs. The founders, sponsors, participants,and techniques of Farm Forum are reported in the section on radio andfilms, which examines the origins1 iDurpose, and background for discussionfor Citizens' Forum. the use of documentary films inadult education; Women's Institutes; rural programs such as the Antigonish Movement and theCommunity Life Training Institute. A bibliography of Canadian writing on adult education is included. (n1) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE i PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

1-888-355-7744 Toll Free 902-567-3000 Local

celtic-colours•com REMOVE MAP TO USE Official Festival Map MAP LEGEND Community Event Icons Meat Cove BAY ST. LAWRENCE | Capstick Official Learning Outdoor Participatory Concert Opportunities Event Event ST. MARGARET'S VILLAGE | ASPY BAY | North Harbour Farmers’ Visual Art / Community Local Food White Point Market Heritage Craft Meal Product CAPE NORTH | Smelt Brook Map Symbols Red River SOUTH HARBOUR | Pleasant Bay Participating Road BIG INTERVALE | Community Lone Shieling NEIL’S HARBOUR | Dirt Road Highway Cabot Trail CAPE BRETON HIGHLANDS NATIONAL PARK Cap Rouge TICKETS & INFORMATION 1-888-355-7744 TOLL FREE Keltic Lodge 902-567-3000 LOCAL CHÉTICAMP | Ingonish Beach INGONISH | Ingonish Ferry La Pointe GRAND ÉTANG HARBOUR | Wreck Cove Terre Noire Skir Dhu BELLE CÔTE | ATLANTIC.CAA.CA French River Margaree Harbour North Shore INDIAN BROOK | Chimney Corner East Margaree MARGAREE CENTER | Tarbotvale NORTH EAST MARGAREE | ENGLISHTOWN | Dunvegan MARGAREE FORKS | Big Bras d’Dor NORTH RIVER | SYDNEY MINES | Lake O’Law 16 BROAD COVE | SOUTH WEST MARGAREE | 17 18 15 Bras d’Dor 19 Victoria NEW WATERFORD | 12 14 20 21 Mines Scotchtown SOUTH HAVEN | 13 Dominion INVERNESS | 2 South Bar GLACE BAY | SCOTSVILLE | MIDDLE RIVER | 11 NORTH SYDNEY | ST. ANN'S | Donkin STRATHLORNE | Big Hill BOULARDERIE | 3 PORT MORIEN | 125 SYDNEY | L 10 Westmount A BADDECK | 4 K Ross Ferry E Barachois A COXHEATH | I MEMBERTOU | N 5 S East Lake Ainslie 8 L I 9 7 E 6 SYDNEY RIVER | WAGMATCOOK7 | HOWIE CENTRE | WEST MABOU | 8 Homeville West Lake Ainslie PRIME BROOK | BOISDALE -

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island 381 a Different View from The

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island A different view from the sea: placenaming on Cape Breton Island William Davey Cape Breton University Sydney NS Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT : George Story’s paper A view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming suggests that there are other, complementary methods of collection and analysis than those used by his colleague E. R. Seary. Story examines the wealth of material found in travel accounts and the knowledge of fishers. This paper takes a different view from the sea as it considers the development of Cape Breton placenames using cartographic evidence from several influential historic maps from 1632 to 1878. The paper’s focus is on the shift names that were first given to water and coastal features and later shifted to designate settlements. As the seasonal fishing stations became permanent settlements, these new communities retained the names originally given to water and coastal features, so, for example, Glace Bay names a town and bay. By the 1870s, shift names account for a little more than 80% of the community names recorded on the Cape Breton county maps in the Atlas of the Maritime Provinces . Other patterns of naming also reflect a view from the sea. Landmarks and boundary markers appear on early maps and are consistently repeated, and perimeter naming occurs along the seacoasts, lakes, and rivers. This view from the sea is a distinctive quality of the island’s names. Keywords: Canada, Cape Breton, historical cartography, island toponymy, placenames © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction George Story’s paper The view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming “suggests other complementary methods of collection and analysis” (1990, p. -

150 Books of Influence Editor: Laura Emery Editor: Cynthia Lelliott Production Assistant: Dana Thomas Graphic Designer: Gwen North

READING NOVA SCOTIA 150 Books of Influence Editor: Laura Emery Editor: Cynthia Lelliott Production Assistant: Dana Thomas Graphic Designer: Gwen North Cover photo and Halifax Central Library exterior: Len Wagg Below (left to right):Truro Library, formerly the Provincial Normal College for Training Teachers, 1878–1961: Norma Johnson-MacGregor Photos of Halifax Central Library interiors: Adam Mørk READING NOVA SCOTIA 150 Books of Influence A province-wide library project of the Nova Scotia Library Association and Nova Scotia’s nine Regional Public Library systems in honour of the 150th anniversary of Confederation. The 150 Books of Influence Project Committee recognizes the support of the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage to develop and promote our cultural resources for all Nova Scotians. Final publication date November 2017. Books are our finest calling card to the world. The stories they share travel far and wide, and contribute greatly to our global presence. Books have the power to profoundly express the complex and rich cultural life that makes Nova Scotia a place people want to visit, live, work and play. This year, the 150th Anniversary of Confederation provided Public Libraries across the province with a unique opportunity to involve Nova Scotians in a celebration of our literary heritage. The value of public engagement in the 150 Books of Influence project is demonstrated by the astonishing breadth and quality of titles listed within. The booklist showcases the diversity and creativity of authors, both past and present, who have called Nova Scotia home. -

Locating the Contributions of the African Diaspora in the Canadian Co-Operative Sector

International Journal of CO-OPERATIVE ACCOUNTING AND MANAGEMENT, 2020 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 3 DOI: 10.36830/IJCAM.202014 Locating the Contributions of the African Diaspora in the Canadian Co-operative Sector Caroline Shenaz Hossein, Associate Professor of Business & Society, York University, Canada Abstract: Despite Canada’s legacy of co-operativism, Eurocentrism dominates thinking in the Canadian co- op movement. This has resulted in the exclusion of racialized Canadians. Building on Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s (2014) exposure of the historical fact of African Americans’ alienation from their own cooperativism as well as the mainstream coop movement, I argue that Canadian co-operative studies are limited in their scope and fail to include the contributions of Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC). I also argue that the discourses of the Anglo and Francophone experiences dominate the literature, with mainly white people narrating the Indigenous experience. Finally, I hold that the definition of co-operatives that we use in Canada should include informal as well as formal co-operatives. Guyanese economist C.Y. Thomas’ (1974) work has influenced how Canadians engage in co-operative community economies. However, the preoccupation with formally registered co-operatives excludes many BIPOC Canadians. By only recounting stories about how Black people have failed to make co-operatives “successful” financially, the Canadian Movement has missed many stories of informal co-operatives that have been effective in what they set out to do. Expanding what we mean by co-operatives for the Canadian context will better capture the impact of co-operatives among BIPOC Canadians. Caroline Shenaz Hossein is Associate Professor of Business & Society in the Department of Social Science at York University in Toronto, Canada. -

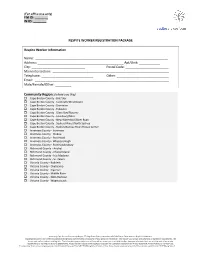

RESPITE WORKER REGISTRATION PACKAGE Respite Worker

(For office use only) FM ID: ________ IN ID: ________ RESPITE WORKER REGISTRATION PACKAGE Respite Worker Information Name: __________________________________________________________________________ Address: ________________________________________________ Apt/Unit: ____________ City: ______________________________ Postal Code: ________________________ Main Intersection: _________________________________________________________________ Telephone: _____________________________ Other: _____________________________ Email: ___________________________________________________________________________ Male/Female/Other: _________ Community Region: (where you live) Cape Breton County - Bras’dor Cape Breton County - Coxheath/Westmount Cape Breton County - Dominion Cape Breton County - Eskasoni Cape Breton County - Glace Bay/Reserve Cape Breton County - Louisburg/Mira Cape Breton County - New Waterford/River Ryan Cape Breton County - Sydney Mines/North Sydney Cape Breton County - Sydney/Sydney River/Howie Center Inverness County - Inverness Inverness County - Mabou Inverness County - Port Hood Inverness County - Whycocomagh Inverness County - Port Hawkesbury Richmond County - Arichat Richmond County - Chapel Island Richmond County - Isle Madame Richmond County - St. Peters Victoria County - Baddeck Victoria County - Cheticamp Victoria County - Ingonish Victoria County - Middle River Victoria County - Neils Harbour Victoria County - Wagmatcook Hosted by Cape Breton Community Respite 77 Kings Road Sydney, Nova Scotia B1P 6H2 -

A United Church Presence in the Antigonish Movement: J.W.A. Nicholson and J.D.N

A United Church Presence in the Antigonish Movement: J.W.A. Nicholson and J.D.N. MacDonald JOHN H. YOUNG School of Religion, Queen’s University The Antigonish Movement, centred around the Extension Department of St. Francis Xavier University, represented a particular response to the poverty gripping much of the rural Maritimes even prior to the onset of the Depression. Moses Coady and Jimmy Tompkins, the two key leaders, were Roman Catholic priests; most of the next echelon of leaders and key workers in the Movement were also Roman Catholic. However, some clergy and lay members of other denominations either supported, or played an active role in, the Antigonish Movement, including two United Church ministers – J.W.A. Nicholson and J.D.N. MacDonald. This essay will briefly examine these two individuals, their motivations, the nature of their involvement, and the way in which they were perceived within the United Church, both during and subsequent to their direct involvement in the Antigonish Movement. J.W.A. Nicholson (1874-1961) was a contemporary of Coady and Tompkins. Born in 1874 in Cape Breton, as a young man he attended Pine Hill Divinity Hall in Halifax, then a Presbyterian college serving the Maritimes. After completing his B.D., he did post-graduate study in Edinburgh, followed by a period of study at the University of Berlin. After an initial pastorate in the Saint John area, Nicholson served at Inverness in Cape Breton from 1905-1911. He then took a call to St. James Presbyterian Church in Dartmouth, where he stayed until 1927. -

Learning Communities

A REVIEW OF THE STATE OF THE FIELD OF ADULT LEARNING LEARNING COMMUNITIES May 2006 Donovan Plumb Mount Saint Vincent University Robert McGray This State of the Field Review was funded by a contribution from the Canadian Council on Learning TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 2 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................4 SECTION A: REVIEW OF EXISTING THEMATIC AREA KNOWLEDGE ......................6 Databases Searched...................................................................................................................................................6 Key Terms Searched ..................................................................................................................................................7 Citizenship, Governance, and Justice .........................................................................................................................8 Community Development...........................................................................................................................................9 Co-operative and Sustainable Economy ...................................................................................................................20 Environment and Transportation ............................................................................................................................23 -

Bishop James Morrison and the Origins of the Antigonish Movement Jacob Remes

Document generated on 10/01/2021 12:05 a.m. Acadiensis In Search of “Saner Minds”: Bishop James Morrison and the Origins of the Antigonish Movement Jacob Remes Volume 39, Number 1, Spring 2010 Article abstract The 1925 United Mine Workers strike in Cape Breton was a crucial turning point URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/acad39_1art03 in the thinking of James Morrison, the bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Antigonish from 1913 to 1950. Before the strike, Morrison had consistently See table of contents opposed the education reforms promoted by his subordinate, Father J.J. Tompkins. The strike encouraged Morrison to fear radical labor unions, which encouraged him accept the creation of the Extension Department at St. Francis Publisher(s) Xavier University. This article, drawing largely on Morrison’s correspondence, traces the evolution of Morrison’s thought within the context of eastern Nova The Department of History at the University of New Brunswick Scotia’s labor history. ISSN 0044-5851 (print) 1712-7432 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Remes, J. (2010). In Search of “Saner Minds”:: Bishop James Morrison and the Origins of the Antigonish Movement. Acadiensis, 39(1), 58–82. All rights reserved © Department of History at the University of New This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Brunswick, 2010 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. -

We Are the Rug Hooking Capital of the World”: Understanding Chéticamp Rugs (1927-2017)

“We are the Rug Hooking Capital of the World”: Understanding Chéticamp Rugs (1927-2017) by © Laura Marie Andrea Sanchini A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University December 3rd, 2018 St John’s Newfoundland Abstract This thesis is the story of how utilitarian material culture was transformed into a cottage industry, and eventually into high art. Chéticamp rug hooking is an artistic practice, one wrapped up in issues of taste, creativity, class and economics. Rug hooking in Chéticamp rose to prominence in the first half of the 20th century when Lillian Burke, a visiting American artist, set up a rug hooking cottage industry in the area. She altered the tradition to suit the tastes of wealthy patrons, who began buying the rugs to outfit their homes. This thesis examines design in rug hooking focusing on Chéticamp-style rugs. Captured within design aesthetics is what the rugs mean to both those who make and consume them. For tourists, the rugs are symbols of a perceived anti-modernism. Through the purchase of a hooked rug, they are able to bring home material reminders of their moment of experience with rural Nova Scotia. For rug hookers, rugs are a symbol of economic need, but also agency and the ability to overcome depressed rural economic conditions. Rug hooking was a way to have a reliable income in an area where much of the labour is dependent on unstable sources, such as natural resources (fishing, lumber, agriculture etc.). -

Who Were Coady and Tompkins?

Who Were Coady and Tompkins? Dr. Moses Michael Coady was born on 3 January 1882 in Margaree Valley, Cape Breton. He was the eldest of 11 children and grew up on a small farm. At the age of 15, Coady attended school and was taught by Chris J. Tompkins, an older cousin and the brother of James (Jimmy) Tompkins. After high school, Coady attended teacher training and worked in Margaree for two years. Following this, he attended the Provincial Normal school in Truro, Nova Scotia, and became a teacher and principal at Margaree Forks. Dr. M. M. Coady, c. 1950.. 77-672-806. Beaton Institute, Cape Breton University. In 1903, Coady registered at St. Francis Xavier University (St. FX) in Antigonish and graduated in 1905 with a bachelor’s degree, successfully achieving a grade A teaching licence. Later that year, he was accepted to the Urban College in Rome, where he studied Theology and Philosophy until 1910. Upon returning to Nova Scotia, he was appointed as a teacher at St. FX’s university high school. He was awarded an MA in Education in 1914 and took over from Jimmy Tompkins as principal of the St. Francis Xavier high school. During this period Moses Coady began to visualize a community development movement and to reflect on the ways that the economic and social status of Nova Scotians might be improved. A priest and educator, Coady helped lead the Antigonish Movement, a people’s movement for economic and social justice that began in Nova Scotia in the 1920s. In 1930 he was appointed to lead the Extension Department of St.