Tun Abdul Razak's National Security Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Flow: Reaching Water Security Through Cooperation; 2013

FREE FLOW REACHING W ATER SECURITY T HROUGH COOPERATION UNESCO Publishing United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization FREE FLOW REACHING W ATER SECURITY T HROUGH COOPERATION UNESCO Publishing United Nations [ Cultural Organization DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. ISBN 978-92-3-104256-0 Original title: Free Flow - Reaching Water Security Through Cooperation Text © UNESCO 2013. All rights reserved. Photographs © as per credits Published in 2013 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and Co-publisher Tudor Rose www.tudor-rose.co.uk UNESCO Publishing United Nations [ Cultural Organization Acknowledgements Compiled by: Sean Nicklin, Ben Cornwell Edited by: Dr Jacqui Griffiths and Rebecca Lambert Designed by: Libby Sidebotham and Paul Robinson Project Manager: Stuart Fairbrother Publication of this book was made possible by: Blanca Jimenez Cisneros, Miguel de França Doria and Alexander Otte at UNESCO-IHP Cover design: Libby Sidebotham Cover image: Tânia Brito, HidroEX Printed in the UK by: Butler, Tanner -

EXPERIENCE in DEVELOPING SOLAR HYBRID SYSTEM for RURAL ELECTRIFICATION in MALAYSIA Khairul Anuar Abd Aziz

Rural Electrification Workshop EXPERIENCE IN DEVELOPING SOLAR HYBRID SYSTEM FOR RURAL ELECTRIFICATION IN MALAYSIA Khairul Anuar Abd Aziz, # TNB Energy Services Sdn Bhd, Malaysia [email protected] Rural Electrification Workshop CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. MODE OF SUPPLY 3. ISSUES AND CONCERN 4. SOLAR HYBRID CONCEPT & OBJECTIVE 5. HOW SOLAR HYBRID OPERATE? 6. LIST OF PROJECT 7. LOCATION OF PROJECT 8. LOAD STUDY & PROFILE 9. DESIGN CONFIGURATION 10. THE CALLANGES 11. PERFORMANCE 12. CONCLUSION Rural Electrification Workshop INTRODUCTION • There are 99.9% community in Malaysia was electrified by National Grid sources. • How about another 0.1%?? • Most of them were living in rural area which located too far from our National Grid sources. • Usually, there are using stand alone generator to produce electricity for their houses. • Cost of energy to produce 1kWh is too high due to high cost of diesel and maintenance of the diesel generator set. • So, as solution, TNB has develop an alternative method in giving supply to this small community known as Solar Hybrid System. Rural Electrification Workshop MODE OF SUPPLY Modes Typical Alternative Grid Extension Diesel Stand Alone Solar Hybrid System Rural Electrification Workshop ISSUES AND CONCERNS OF REMOTE AREAS POWER SUPPLY Grid extension: • High cost • Need extensive and complicated installation works. • Need high voltage system to carry current over long distance. • Geography obstacle i.e Islands • No contribution towards renewable energy. • Pollution shifted to power plants Rural Electrification Workshop ISSUES AND CONCERNS OF REMOTE AREAS POWER SUPPLY Diesel Stand Alone: • Generator set starting failure, requiring unscheduled site visits for fault rectification/ need on-site operator. -

Saad Shauket Sammen

UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA FLOOD MODELING OF DAM BREAK WITH CONSIDERATION OF CLIMATE CHANGE SAAD SHAUKET SAMMEN FK 2018 31 FLOOD MODELING OF DAM BREAK WITH CONSIDERATION OF CLIMATE CHANGE UPM By SAAD SHAUKET SAMMEN COPYRIGHT © Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 All material contained within the thesis, including without limitation text, logos, icons, photographs and all other artwork, is copyright material of Universiti Putra Malaysia unless otherwise stated. Use may be made of any material contained within the thesis for non-commercial purposes from the copyright holder. Commercial use of material may only be made with the express, prior, written permission of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Copyright © Universiti Putra Malaysia UPM COPYRIGHT © i DEDICATION To UPM My Parents COPYRIGHT © ii Abstract of the thesis presented to the Senate of Universiti Putra Malaysia in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy FLOOD MODELING OF DAM BREAK WITH CONSIDERATION OF CLIMATE CHANGE By SAAD SHAUKET SAMMEN December 2017 UPM Chairman : Professor Thamer Ahmad Mohammed Ali, PhD Faculty : Engineering In this study, the failure of cascade dams in a tropical region is simulated using mathematical models. The simulation is considering the climate change impact. Three cascade dams for hydropower generation on the Perak River were taken as case studies. The three dams are of different designs, ages and heights which make a unique complex dam system. The proposed models were categorized as dam breach parameters model, hydrological model and hydrodynamic models. -

MTC-PJC to Build Malaysia's Longest Glulam Bridge

timber VO L . 22 NO. 3 2016 ISSN 1394-6196 malaysiaPublished by Malaysian Timber Council New Minister and Deputy Minister of Plantation Industries and Commodities MTC dialogue with timber association members Sporting excellence with KTL floors Cover Story MTC-PJC to build Malaysia’s longest Glulam bridge 2 EDITORIAL Vol. 22 No. 3 Timber Malaysia Dear Readers, His Hon. Datuk Seri Mah Siew Keong Council’s programmes and activities are in has been appointed the new Minister of tune with the industry’s expectations and Plantation Industries and Commodities. requirements (turn to page 4). He replaces His Hon. Datuk Amar Douglas Uggah Embas who is now a Deputy Chief Under SPOTLIGHT, we highlight the HMinister in his home state of Sarawak. journey of Kim Teck Lee (KTL), a We congratulate Datuk Seri Mah on his timber-based company that started off appointment and, at the same time, thank in the mid-sixties as a sawmill but has Datuk Amar Douglas for his stewardship diversified over the past half century into during his tenure as Minister of Plantation a leading manufacturer and exporter of Industries and Commodities. Among the value added timber products including many issues that had always remained high mouldings, lam parquet and prefinished on Datuk Amar Douglas’s agenda were flooring. The most successful yet is their the Malaysia-EU FLEGT-VPA negotiations, range of high quality sports flooring which when completed will ensure a which has taken the world by storm with ‘green’ lane for Malaysia’s timber exports import orders coming from Europe, the to EU countries. -

The Perak Development Experience: the Way Forward

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences December 2013, Vol. 3, No. 12 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Perak Development Experience: The Way Forward Azham Md. Ali Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management and Economics Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 Speech for the Menteri Besar of Perak the Right Honourable Dato’ Seri DiRaja Dr Zambry bin Abd Kadir to be delivered on the occasion of Pangkor International Development Dialogue (PIDD) 2012 I9-21 November 2012 at Impiana Hotel, Ipoh Perak Darul Ridzuan Brothers and Sisters, Allow me to briefly mention to you some of the more important stuff that we have implemented in the last couple of years before we move on to others areas including the one on “The Way Forward” which I think that you are most interested to hear about. Under the so called Perak Amanjaya Development Plan, some of the things that we have tried to do are the same things that I believe many others here are concerned about: first, balanced development and economic distribution between the urban and rural areas by focusing on developing small towns; second, poverty eradication regardless of race or religion so that no one remains on the fringes of society or is left behind economically; and, third, youth empowerment. Under the first one, the state identifies viable small- and medium-size companies which can operate from small towns. These companies are to be working closely with the state government to boost the economy of the respective areas. -

Tropical Wetland Valuation: an Influence of Local Knowledge in Malay Traditional Ecosystem for Human Well-Being

SHS Web of Conferences 45, 03002 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20184503002 ICLK 2017 Tropical Wetland Valuation: An influence of local knowledge in Malay traditional ecosystem for human well-being Farah Mastura Rosli,2, Anizah Salleh2, Widad Fadhlullah3, Mahamad Hakimi Ibrahim3, and Norizan Esa1* 1School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia 2Faculty of Technical and Vocational, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Tanjong Malim, Perak Darul Ridzuan 35900, Malaysia 3School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia Abstract. Tropical wetlands are among the most productive ecosystems on earth which provide vital services and consist of various types of plant and animal communities that live in the water and on land. However, this golden area is one of the most undervalued ecosystems and the awareness on protecting the areas is still lacking among communities. The aim of this study was to review the wetland services in a tropical climate which functions to complete the ecosystem. In particular, this study will i) explore the values of wetland ecosystem towards human well-being in tropical culture and ii) to design a complete wetland ecosystem with respect to the local knowledge in a tropical climate. This study indicates that the new millennium of ecosystem services provided by tropical wetland has been disaggregated into provisioning of goods; regulating services, cultural development and supporting the process by considering the influence of Malay traditional wetland. Therefore, a complete tropical ecosystem is designed by imitating the natural wetland for societal well-being. 1 Introduction Wetlands play a vital role in human societies, accommodating a habitat and source of food for various types of plants and animals, supplying clean and retaining water naturally. -

Image Quality Enhancement Using Pixel-Wise Gamma Correction

Iranica Journal of Energy and Environment 7(2): 177-183, 2016 Iranica Journal of Energy & Environment Journal Homepage: www.ijee.net IJEE an official peer review journal of Babol Noshirvani University of Technology, ISSN:2079-2115 Stable Isotopes Approach to Infer the Feeding Habit and Trophic Position of Freshwater Fishes in Tropical Lakes S. K. Yap1, I. Muneera2, M. I. Syakir 1, H.H. Zarul2 and *Widad F.1 1Environmental Technology, School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, USM 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. 2School of Biological Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 USM, Penang, Malaysia. ABSTRACT P A P E R I N F O A study was conducted on the stable isotope variation of muscle tissues from selected freshwater fish Paper history: species from Temenggor Lake and Chenderoh Lake, Perak, Malaysia from December 2014 to March Received 7 December 2015 2015. The objective is to assess the stable isotopes of δ13C to identify the carbon sources and δ15N of Accepted in revised form 13 December 2015 fish species from Temenggor and Chenderoh Lake, Perak, Malaysia to infer the trophic position of these fishes. Four types of fish species were analyzed by using stable isotope approach which were Hampala barb (Hampala macrolepidota), Oxygaster cyprinus (Oxygaster anomalura), Peacock Bass Keywords: (Cichla ocellaris) and Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Stable isotopes of δ13C and δ15N were stable isotopes analysed using an elemental analyser Thermo Finnigan Flash EA 2000 connected to Finningan Food webs DELTA V AVANTAGE plus isotope ratio mass spectrometry by a ConFlo II interface. The δ13C Freshwater fishes 15 δ13C values from both lakes implies a C3 phytoplankton as reported from the literature. -

Download Malaysia Brochure

Malaysia Gulf of South China Sulu Sea Thailand Sea Layang Layang Thailand Turtle Islands Park KOTA Kinabalu KINABALU Park Sandakan Labuan Gomantong Malaysian Caves BANDAR MALAYSIA Malaysia Brunei SERI Sabah Borneo BEGAWAN Miri Sipidan Island Mulu KUALA LUMPUR National Park Bako Sarawak See our Sibu National Kapit Borneo Damai Beach Park Brochure for SINGAPORE Batang Ai more details. KUCHING WELCOME TO TO WELCOME China Taiwan Laos Indonesia Philippines Vietnam IndonesiaThailand Cambodia Malaysia Celebes Papua New Guinea SINGAPORE Borneo Sea Indonesia Contents Highlights of Malaysia ������������������������������������������������������������3 Australia Travel Tips ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 Kuala Lumpur �����������������������������������������������������������4 Kuala Lumpur Resorts and Hotels �������������������������������������5-6 Kuala Lumpur Day Tours ��������������������������������������������������������7 Malaysia Holidays offer great value airfares when combining Malacca Escapade Tour...........................................................8 air travel with hotel and tour arrangements. Cameron Highlands Tour ��������������������������������������������������������8 Colonial Malaysia Tour ������������������������������������������������������������9 Malaysia Holidays can arrange car hire from most Round Malaysia Tour ����������������������������������������������������������� 10 Malaysian cities. Contact Taman Negara Explorer Tour �����������������������������������������������10 -

Condition Factor, Catch Per Unit Effort, Environmental

UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA CONDITION FACTOR, CATCH PER UNIT EFFORT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITION AND MIGRATORY PATTERN OF Thynnichthys thynnoides (BLEEKER, 1852) FOR FISHERIES MANAGEMENT AT RUI RIVER, PERAK, MALAYSIA UPM MOHAMAD RADHI BIN AMONODIN COPYRIGHT © FPAS 2017 5 CONDITION FACTOR, CATCH PER UNIT EFFORT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITION AND MIGRATORY PATTERN OF Thynnichthys thynnoides (BLEEKER, 1852) FOR FISHERIES MANAGEMENT AT RUI RIVER, PERAK, MALAYSIA UPM By MOHAMAD RADHI BIN AMONODIN COPYRIGHT © Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science March 2017 i COPYRIGHT All material contained within the thesis, including without limitation text, logos, icons, photographs and all other artwork, is copyright material of Universiti Putra Malaysia unless otherwise stated. Use may be made of any material contained within the thesis for non-commercial purposes from the copyright holder. Commercial use of material may only be made with the express, prior, written permission of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Copyright © Universiti Putra Malaysia UPM COPYRIGHT © ii Abstract of thesis presented to the Senate of Universiti Putra Malaysia in fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Science CONDITION FACTOR, CATCH PER UNIT EFFORT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITION AND MIGRATORY PATTERN OF Thynnichthys thynnoides (BLEEKER, 1852) FOR FISHERIES MANAGEMENT AT RUI RIVER, PERAK, MALAYSIA By MOHAMAD RADHI BIN AMONODIN March 2017 UPM Chairman : Rohasliney Hashim, PhD Faculty : Environmental Studies This study had been carried out to find out the condition factor, environmental condition and migratory pattern of tiny scale barb Thynnichthys thynnoides in the Rui River, Gerik, Perak. Eight sampling sites were chosen and located in the main channel of the Perak River and its tributary, Rui River, comprising the upstream, middle stream and lower stream of the river system. -

Pdf (740.35 K)

Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. ISSN 1110 – 6131 Vol. 24(3): 311 – 322 (2020) www.ejabf.journals.ekb.eg Origin of Invasive Fish Species, Peacock Bass Cichla Species in Lake Telabak Malaysia Revealed by Mitochondrial DNA Barcoding Aliyu G. Khaleel1,2, Syafiq A. M. Nasir1, Norshida Ismail1, 1, and Kamarudin Ahmad-Syazni * 1 School of Animal Science, Faculty of Bioresources and Food Industry, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin, Besut Campus, 22200 Besut, Terengganu, Malaysia. 2 Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Agriculture and Agricultural Technology, Kano University of Science and Technology, Wudil, P.M.B. 3244 Kano State, Nigeria. *Corresponding author: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Peacock bass (Perciformes, Cichlidae, Cichla) are multi-coloured and Received: Nov. 18, 2019 highly predatory fish originated from Amazonian region. The species was Accepted: April 27, 2020 deliberately introduced into Malaysia freshwater bodies by anglers in the early Online: May 2020 1990’s for sport fisheries. In this recent study, we found the population of _______________ peacock bass in Lake Telabak, a man-made lake in Besut, Terengganu. Using mitochondrial DNA analysis approach, the origin and taxonomy of peacock Keywords: bass in the lake were clarify. A total of forty fishes were sampled from Lake Peacock bass, Telabak for the analysis. Haplotype was detected among all samples. The Invasive species, current study revealed that Cichla spp. in Lake Telabak are closer to Cichla mitochondrial DNA ocellaris (Bloch and Schneider, 1801) with a sequence similarity of 99.72% barcoding, Lake Telabak as blasted at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. -

Hulu Sungai Perak Bed Sediment Mapping Using Underwater Acoustic Sonar

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-4/W1, 2016 International Conference on Geomatic and Geospatial Technology (GGT) 2016, 3–5 October 2016, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia HULU SUNGAI PERAK BED SEDIMENT MAPPING USING UNDERWATER ACOUSTIC SONAR N. Arriafdia, O. Zainona, U. Dina, A. W. Rasida, Z. Mat Amina, R. Othmana, A. S. Mardia, R. Mahmuda, N. Sulaimanb aDepartment of Geoinformation, Faculty of Geoinformation and Real Estate, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310 Johor Bahru. Johor. bDepartment of Survey and Mapping Malaysia, 50578 Kuala Lumpur. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] KEY WORDS: Side Scan Sonar, Riverbed Sediment, Correlation, Backscatter, Signal Strength, Image Analysis ABSTRACT: Development in acoustic survey techniques in particular side scan sonar have revolutionized the way we are able to image, map and understand the riverbed environment. It is now cost effective to image large areas of the riverbed using these techniques and the backscatter image created from surveys provides base line data from which thematic maps of the riverbed environment including maps of morphological geology, can be derived when interpreted in conjunction with in situ sampling data. This article focuses on investigation characteristics of sediments and correlation of side scan backscatter image with signal strength. The interpretation of acoustic backscatter rely on experienced interpretation by eye of grey scale images produced from the data. A 990F Starfish Side Scan Sonar was used to collect and develop a series of sonar images along 6 km of Hulu Sungai Perak. -

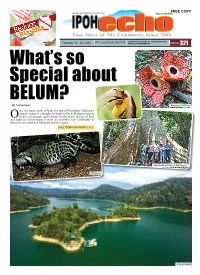

Ipoh Echo Issue

FREE COPY PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – February 16 - 29, 2020 ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR ISSUE 321 What’s so Special about BELUM? By Vivien Lian Blooming Rafflesia nly two hours north of Ipoh lies one of Peninsular Malaysia’s natural treasures, a hotspot for biodiversity in Malaysia hosting Odiverse ecosystems and habitats for the many species of flora and fauna of which many of them are endemic, rare, vulnerable or otherwise threatened in Malaysia and the region. FULL STORY ON PAGES 2 & 6 Enormous old tree in Temenggor Wild civet Khong Island YOUR VOICE IN THE COMMUNITY 2 IE321 February 16 - 29, 2020 www.ipohecho.com.my Ipoh Echo Foodie Guide Ipoh Echo Something for everyone, from the intrepid to the laid back 2 Pillbox Jahai tribe of Orang Asli oyal Belum is famous for its state park which was With a variety of waterfalls, indigenous villages, gazetted as a protected area on May 3, 2007, under salt-licks, interesting plants, animals and insects, there Rthe Perak State Parks Corporation Enactment is much to do and it is this rich biodiversity that attracts 2001. The 130-million-year-old rainforest covering local and foreign visitors who flock to Royal Belum. 117,500 hectares is amongst the oldest in the world, vying Salt licks are natural salt deposits which animals for seniority with the forests of the Amazon, Congo, and regularly lick to get their much-needed mineral others. sustenance. Wild animals often leave their faeces around Consisting mainly of primary forests, it boasts the place to mark their territory.