Parry's Forgotten Discoveries 1849-51

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malosma Laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. Ex Abrams

I. SPECIES Malosma laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. ex Abrams NRCS CODE: Family: Anacardiaceae MALA6 Subfamily: Anacardiodeae Order: Sapindales Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Immature fruits are green to red in mid-summer. Plants tend to flower in May to June. A. Subspecific taxa none B. Synonyms Rhus laurina Nutt. (USDA PLANTS 2017) C. Common name laurel sumac (McMinn 1939, Calflora 2016) There is only one species of Malosma. Phylogenetic analyses based on molecular data and a combination of D. Taxonomic relationships molecular and structural data place Malosma as distinct but related to both Toxicodendron and Rhus (Miller et al. 2001, Yi et al. 2004, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). E. Related taxa in region Rhus ovata and Rhus integrifolia may be the closest relatives and laurel sumac co-occurs with both species. Very early, Malosma was separated out of the genus Rhus in part because it has smaller fruits and lacks the following traits possessed by all species of Rhus : red-glandular hairs on the fruits and axis of the inflorescence, hairs on sepal margins, and glands on the leaf blades (Barkley 1937, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). F. Taxonomic issues none G. Other The name Malosma refers to the strong odor of the plant (Miller & Wilken 2017). The odor of the crushed leaves has been described as apple-like, but some think the smell is more like bitter almonds (Allen & Roberts 2013). The leaves are similar to those of the laurel tree and many others in family Lauraceae, hence the specific epithet "laurina." Montgomery & Cheo (1971) found time to ignition for dried leaf blades of laurel sumac to be intermediate and similar to scrub oak, Prunus ilicifolia, and Rhamnus crocea; faster than Heteromeles arbutifolia, Arctostaphylos densiflora, and Rhus ovata; and slower than Salvia mellifera. -

Annotated Check List and Host Index Arizona Wood

Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood-Rotting Fungi Item Type text; Book Authors Gilbertson, R. L.; Martin, K. J.; Lindsey, J. P. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 28/09/2021 02:18:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/602154 Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood - Rotting Fungi Technical Bulletin 209 Agricultural Experiment Station The University of Arizona Tucson AÏfJ\fOTA TED CHECK LI5T aid HOST INDEX ford ARIZONA WOOD- ROTTlNg FUNGI /. L. GILßERTSON K.T IyIARTiN Z J. P, LINDSEY3 PRDFE550I of PLANT PATHOLOgY 2GRADUATE ASSISTANT in I?ESEARCI-4 36FZADAATE A5 S /STANT'" TEACHING Z z l'9 FR5 1974- INTRODUCTION flora similar to that of the Gulf Coast and the southeastern United States is found. Here the major tree species include hardwoods such as Arizona is characterized by a wide variety of Arizona sycamore, Arizona black walnut, oaks, ecological zones from Sonoran Desert to alpine velvet ash, Fremont cottonwood, willows, and tundra. This environmental diversity has resulted mesquite. Some conifers, including Chihuahua pine, in a rich flora of woody plants in the state. De- Apache pine, pinyons, junipers, and Arizona cypress tailed accounts of the vegetation of Arizona have also occur in association with these hardwoods. appeared in a number of publications, including Arizona fungi typical of the southeastern flora those of Benson and Darrow (1954), Nichol (1952), include Fomitopsis ulmaria, Donkia pulcherrima, Kearney and Peebles (1969), Shreve and Wiggins Tyromyces palustris, Lopharia crassa, Inonotus (1964), Lowe (1972), and Hastings et al. -

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens Francisco Garin Garcia Iturraran Botanical Gardens, northern Spain [email protected] Overview Iturraran Botanical Gardens occupy 25 hectares of the northern area of Spain’s Pagoeta Natural Park. They extend along the slopes of the Iturraran hill upon the former hay meadows belonging to the farmhouse of the same name, currently the Reception Centre of the Park. The minimum altitude is 130 m above sea level, and the maximum is 220 m. Within its bounds there are indigenous wooded copses of Quercus robur and other non-coniferous species. Annual precipitation ranges from 140 to 160 cm/year. The maximum temperatures can reach 30º C on some days of summer and even during periods of southern winds on isolated days from October to March; the winter minimums fall to -3º C or -5 º C, occasionally registering as low as -7º C. Frosty days are few and they do not last long. It may snow several days each year. Soils are fairly shallow, with a calcareous substratum, but acidified by the abundant rainfall. In general, the pH is neutral due to their action. Collections The first plantations date back to late 1987. There are currently approximately 5,000 different taxa, the majority being trees and shrubs. There are around 3,000 species, including around 300 species from the genus Quercus; 100 of them are from Mexico and Central America. Quercus costaricensis photo©Francisco Garcia 48 International Oak Journal No. 22 Spring 2011 Oaks from Mexico and Oaks from Mexico -

4.2 Agriculture and Forest Resources

4.2 Agriculture and Forest Resources 4.2 AGRICULTURE AND FOREST RESOURCES This section evaluates the potential impacts to agriculture and forest resources associated with implementation of the 2050 RTP/SCS. The information presented was compiled from multiple sources, including the County of San Diego, the State of California Department of Conservation (DOC), the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), CAL FIRE, and local jurisdictions. 4.2.1 EXISTING CONDITIONS Agriculture Overview of Agriculture in the Region Agriculture is not only an important contributor to the economy of the San Diego region; it also is a primary land use in the unincorporated area of the region. San Diego County contains 6,687 farms and agriculture ranked fifth as a component of the region’s economic resources (County of San Diego 2010). San Diego County is the 16th largest agricultural economy among all counties in the nation. The region’s unique topography creates a wide variety of microclimates resulting in nearly 30 different types of vegetation communities. This diversity allows San Diego farmers to grow over 200 different agricultural commodities, such as strawberries along the coast, apples in the mountain areas, and palm trees in the desert (County of San Diego 2010). The region ranks first in both California and the nation in production value of nursery plants, floriculture, and avocados. Statewide, San Diego County is in the top five counties for producing cucumbers, mushrooms, tomatoes, boysenberries and strawberries, grapefruit, Valencia oranges, tangelos and tangerines, honey, and eggs. San Diego County has the largest community of organic growers in the state and nation, with 374 farms growing more than 175 crops (County of San Diego 2009). -

Agave Shawii Var Shawii - Shaw's Agave

Agave shawii var shawii - Shaw's agave Most Year of Most Occurrence Land Natural Occurrence ID IMA? MU Preserve Land Owner Recent Recent Pop Threats Source Name Manager Population? Pop Size Survey AGSH_1BFSP001 Yes 1 Border Field State Border Field California California 1 2011 Yes Biggest threat is loss of individuals. Threat to out- MOM; Park State Park Department Department crossing given life history traits and small number of Vanderplank of Parks and of Parks and individuals. Sexual reproduction and seedling 2012; Masilko Recreation Recreation recruitment are low for this taxon. 2007 AGSH_1CNMO002 Yes 1 Cabrillo National Cabrillo National National 30 2011 Partially Biggest threat is loss of individuals. Sexual MOM; Rare Monument National Park Service Park Service reproduction and seedling recruitment low for this Plant 2016; Monument taxon. Other threats include direct impacts and Vanderplank human trespassing. Low level of nonnative forbs and 2012 grasses and competition with native plants. Erosion and roads/trails are adjacent to occurrence. Some plants fall within landscaped areas. AGSH_1TISL003 No 1 Tijuana Slough Tijuana U.S. Fish U.S. Fish 88 2016 No Altered hydrology and urban runoff in over 75% of MOM; Rare NWR Visitor Slough and Wildlife and Wildlife mapped occupied extent. Some threat from soil Plant 2016; Center National Service Service compaction. Authorized trails and human use near CCH 2013; Wildlife plants which are highly managed as part of Reiser 1994 Refuge landscaping at visitor center. AGSH_7SCSB006 Yes 6 South Carlsbad South California California 1 2015 No Nonnative forbs, nonnative grasses, nonnative Rare Plant State Beach Carlsbad Department Department woody plants, trash dumping, trampling, erosion and 2014, 2015 State Beach of Parks and of Parks and slope movement. -

Relative Genetic Diversity of the Rare and Endangered Agave Shawii Ssp

Received: 17 July 2020 | Revised: 9 December 2020 | Accepted: 14 December 2020 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.7172 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Relative genetic diversity of the rare and endangered Agave shawii ssp. shawii and associated soil microbes within a southern California ecological preserve Jeanne P. Vu1 | Miguel F. Vasquez1 | Zuying Feng1 | Keith Lombardo2 | Sora Haagensen1,3 | Goran Bozinovic1,4 1Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, San Diego, CA, USA Abstract 2Southern California Research Learning Shaw's Agave (Agave shawii ssp. shawii) is an endangered maritime succulent growing Center, National Park Services, San Diego, along the coast of California and northern Baja California. The population inhabiting CA, USA 3University of California San Diego Point Loma Peninsula has a complicated history of transplantation without documen- Extended Studies, La Jolla, CA, USA tation. The low effective population size in California prompted agave transplanting 4 Biological Sciences, University of California from the U.S. Naval Base site (NB) to Cabrillo National Monument (CNM). Since 2008, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA there are no agave sprouts identified on the CNM site, and concerns have been raised Correspondence about the genetic diversity of this population. We sequenced two barcoding loci, rbcL Goran Bozinovic, Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, 3030 Bunker Hill St, and matK, of 27 individual plants from 5 geographically distinct populations, includ- San Diego CA 92109, USA. ing 12 individuals from California (NB and CNM). Phylogenetic analysis revealed the Emails: [email protected]; gbozinovic@ ucsd.edu three US and two Mexican agave populations are closely related and have similar ge- netic variation at the two barcoding regions, suggesting the Point Loma agave popu- Funding information National Park Services (NPS) Pacific West lation is not clonal. -

How to Look at Oaks

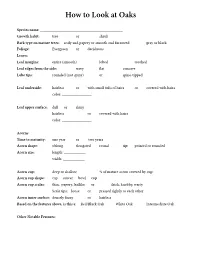

How to Look at Oaks Species name: __________________________________________ Growth habit: tree or shrub Bark type on mature trees: scaly and papery or smooth and furrowed gray or black Foliage: Evergreen or deciduous Leaves Leaf margins: entire (smooth) lobed toothed Leaf edges from the side: wavy fat concave Lobe tips: rounded (not spiny) or spine-tipped Leaf underside: hairless or with small tufs of hairs or covered with hairs color: _______________ Leaf upper surface: dull or shiny hairless or covered with hairs color: _______________ Acorns Time to maturity: one year or two years Acorn shape: oblong elongated round tip: pointed or rounded Acorn size: length: ___________ width: ___________ Acorn cup: deep or shallow % of mature acorn covered by cup: Acorn cup shape: cap saucer bowl cup Acorn cup scales: thin, papery, leafike or thick, knobby, warty Scale tips: loose or pressed tightly to each other Acorn inner surface: densely fuzzy or hairless Based on the features above, is this a: Red/Black Oak White Oak Intermediate Oak Other Notable Features: Characteristics and Taxonomy of Quercus in California Genus Quercus = ~400-600 species Original publication: Linnaeus, Species Plantarum 2: 994. 1753 Sections in the subgenus Quercus: Red Oaks or Black Oaks 1. Foliage evergreen or deciduous (Quercus section Lobatae syn. 2. Mature bark gray to dark brown or black, smooth or Erythrobalanus) deeply furrowed, not scaly or papery ~195 species 3. Leaf blade lobes with bristles 4. Acorn requiring 2 seasons to mature (except Q. Example native species: agrifolia) kelloggii, agrifolia, wislizeni, parvula 5. Cup scales fattened, never knobby or warty, never var. -

V. R. Todd and R. E. Learned and Thomas J. Peters and Ronald T

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-1547-A ^UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE SILL HILL, HADSER, AND CALIENTE ROADLESS AREAS, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SUMMARY REPORT By V. R. Todd and R. E. Learned U.S. Geological Survey and Thomas J. Peters and Ronald T. Mayerle U.S. Bureau of Mines STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Under the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964) and the Joint Conference Report on Senate Bill 4, 88th Congress, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preservation System, and some of them are presently being studied. The act provided that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the results of min eral surveys of the Sill Hill (5-304), Hauser (5-021), and Caliente (5-017) Roadless Areas, Cleveland National Forest, San Diego dpunty, California. SUMMARY The Sill Hill, Hauser, and Caliente Roadless Areas comprise approximately 20,000 acres in the Cleveland National Forest, San Diego County, Calif, (fig. 1). Geological and geochemical investigations have been conducted by the U.S. -

Oaks of the Wild West Inventory Page 1 Nursery Stock Feb, 2016

Oaks of the Wild West Inventory Nursery Stock Legend: AZ = Arizona Nursery TX = Texas Nursery Feb, 2016 *Some species are also available in tube sizes Pine Trees Scientific Name 1G 3/5G 10G 15 G Aleppo Pine Pinus halapensis AZ Afghan Pine Pinus elderica AZ Apache Pine Pinus engelmannii AZ Chinese Pine Pinus tabulaeformis AZ Chihuahua Pine Pinus leiophylla Cluster Pine Pinus pinaster AZ Elderica Pine Pinus elderica AZ AZ Italian Stone Pine Pinus pinea AZ Japanese Black Pine Pinus thunbergii Long Leaf Pine Pinus palustris Mexican Pinyon Pine Pinus cembroides AZ Colorado Pinyon Pine Pinus Edulis AZ Ponderosa Pine Pinus ponderosa AZ Scotch Pine Pinus sylvestre AZ Single Leaf Pine Pinus monophylla AZ Texas Pine Pinus remota AZ, TX Common Trees Scientific Name 1G 3/5G 10G 15 G Arizona Sycamore Platanus wrightii ** Ash, Arizona Fraxinus velutina AZ AZ Black Walnut, Arizona Juglans major AZ AZ Black Walnut, Texas Juglans microcarpa TX Black Walnut juglans nigra AZ, TX Big Tooth Maple Acer grandidentatum AZ Carolina Buckthorn Rhamnus caroliniana TX Chitalpa Chitalpa tashkentensis AZ Crabapple, Blanco Malus ioensis var. texana Cypress, Bald Taxodium distichum AZ Desert Willow Chillopsis linearis AZ AZ Elm, Cedar Ulmus crassifolia TX TX Ginko Ginkgo biloba TX Hackberry, Canyon Celtis reticulata AZ AZ AZ Hackberry, Common Celtis occidentalis TX Maple (Sugar) Acer saccharum AZ AZ Mexican Maple Acer skutchii AZ Mexican Sycamore Platanus mexicana ** Mimosa, fragrant Mimosa borealis Page 1 Oaks of the Wild West Inventory Pistache (Red Push) Pistacia -

And Engelmann Oak (Q. Engelmannii) at the Acorn and Seedling Stage1

Insect-oak Interactions with Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) and Engelmann Oak (Q. engelmannii) at the Acorn and Seedling Stage1 Connell E. Dunning,2 Timothy D. Paine,3 and Richard A. Redak3 Abstract We determined the impact of insects on both acorns and seedlings of coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia Nee) and Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii E. Greene). Our goals were to (1) identify insects feeding on acorns and levels of insect damage, and (2) measure performance and preference of a generalist leaf-feeding insect herbivore, the migratory grasshopper (Melanoplus sanguinipes [Fabricus] Orthoptera: Acrididae), on both species of oak seedlings. Acorn collections and insect emergence traps under mature Q. agrifolia and Q. engelmannii revealed that 62 percent of all ground-collected acorns had some level of insect damage, with Q. engelmannii receiving significantly more damage. However, the amount of insect damage to individual acorns of both species was slight (<20 percent damage per acorn). Curculio occidentis (Casey) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), Cydia latiferreana (Walsingham) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), and Valentinia glandulella Riley (Lepidoptera: Blastobasidae) were found feeding on both species of acorns. No-choice and choice seedling feeding trials were performed to determine grasshopper performance on the two species of oak seedlings. Quercus agrifolia seedlings and leaves received more damage than those of Q. engelmannii and provided a better diet, resulting in higher grasshopper biomass. Introduction The amount of oak habitat in many regions of North America is decreasing due to increased urban and agricultural development (Pavlik and others 1991). In addition, some oak species are exhibiting low natural regeneration. Although the status of Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii E. -

January 2017

TORREYANA THE DOCENT NEWSLETTER FOR TORREY PINES STATE NATURAL RESERVE Issue 380 January 2017 Another Successful Docent Holiday Party Docent General Meeting by Ray Barger Saturday, January 14, 9 am arly morning overcast skies gave way to bursts of sunshine Location: St. Peter’s Episcopal Rec Hall, Del Mar E for the approximately 140 guests at the 2016 Torrey Pines holiday potluck party held on Saturday, December 10 at Torrey Speaker: Bob Guza, Professor Emeritus, Scripps Circle next to the Lodge. Institution of Oceanography Topic: Beach Sand Loss Prof. Guza received his BA from Johns Hopkins University and his MS and PhD from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. His research has included beach and cliff erosion; pollution transport and dilution in the surf zone; and regional wave networks. Refreshments: Docents with last names beginning with A– C will be responsible for providing snacks for this meeting. Ingo expressed his appreciation saying, “Thank you, Class of 2016, for your terrific job in hosting a very successful holiday party. Folks had a great time bonding and this is an important aspect of keeping our docent society strong and fun!” Photo by Ray Barger The Class of 2016 extends our gratitude to the many experienced docents who helped us conduct a successful, memorable holiday Hosted by the Class of 2016, who also decorated the Lodge, the event. In particular we party featured mulled wine and a wonderful collection of potluck recognize Denise Rivera Inside appetizers, main dishes, side dishes, and desserts prepared by the (Lodge decorations leader), President’s Letter 2 attendees. -

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This Chapter Presents an Overall Summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the Water Resources on Their Reservations

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This chapter presents an overall summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the water resources on their reservations. A brief description of each Tribe, along with a summary of available information on each Tribe’s water resources, is provided. The water management issues provided by the Tribe’s representatives at the San Diego IRWM outreach meetings are also presented. 4.1 Reservations San Diego County features the largest number of Tribes and Reservations of any county in the United States. There are 18 federally-recognized Tribal Nation Reservations and 17 Tribal Governments, because the Barona and Viejas Bands share joint-trust and administrative responsibility for the Capitan Grande Reservation. All of the Tribes within the San Diego IRWM Region are also recognized as California Native American Tribes. These Reservation lands, which are governed by Tribal Nations, total approximately 127,000 acres or 198 square miles. The locations of the Tribal Reservations are presented in Figure 4-1 and summarized in Table 4-1. Two additional Tribal Governments do not have federally recognized lands: 1) the San Luis Rey Band of Luiseño Indians (though the Band remains active in the San Diego region) and 2) the Mount Laguna Band of Luiseño Indians. Note that there may appear to be inconsistencies related to population sizes of tribes in Table 4-1. This is because not all Tribes may choose to participate in population surveys, or may identify with multiple heritages. 4.2 Cultural Groups Native Americans within the San Diego IRWM Region generally comprise four distinct cultural groups (Kumeyaay/Diegueno, Luiseño, Cahuilla, and Cupeño), which are from two distinct language families (Uto-Aztecan and Yuman-Cochimi).