Quality of Leaders and Barangay Finance Comparative Ecclesiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

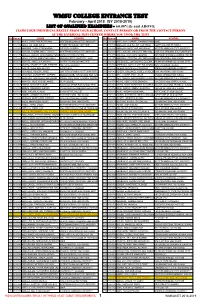

Wmsu College Entrance Test

WMSU COLLEGE ENTRANCE TEST February - April 2018 (SY 2018-2019) LIST OF QUALIFIED EXAMINEES - 60.00%ile and ABOVE CLAIM YOUR INDIVIDUAL RESULT FROM YOUR SCHOOL CONTACT PERSON OR FROM THE CONTACT PERSON AT THE EXTERNAL TEST CENTER WHERE YOU TOOK THE TEST No. Appno NAME SCHOOL No. Appno NAME SCHOOL 1 1819-02011 ABAD, CHRISTIAN BEJERANO WESTERN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY 77 1819-10948 ABELLANA, MARIFE JEAN MARCHAN NONE 2 1819-03458 ABAD, IZA JEAN AWID SYSTEM TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTE 78 1819-06982 ABELLAR, ALEISA JOY CASIPONG CLARET COLLEGE OF ISABELA 3 1819-06571 ABADIES, RHEA CRIS MAGNO AVE MARIA ACADEMY 79 1819-02297 ABELLON, MAY FLOR MAGSALAY WESTERN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY 4 1819-02592 ABAJAR, CHARM ANGEL ACALA WESTERN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY 80 1819-00718 ABELLON, WILJAN JAY TEMPLADO JOSE RIZAL MEMORIAL STATE UNIVERSITY 5 1819-10351 ABALLE, JOMARI JAKE RAMBUYONG MARCELO SPINOLA SCHOOL 81 1819-07670 ABENEZ, JUDY ANN TOLORIO DON RAMON ENRIQUEZ MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL 6 1819-00664 ABANI, FATIMA SHENRADA ADJU MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY - SULU 82 1819-06770 ABENOJA, CRYSTAL JOY GERANGAYABASILAN NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 7 1819-05710 ABANTE, ANGELICA OGANG SYSTEM TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTE 83 1819-00425 ABEQUIBEL, LORDALAINE ELLEMA BALIWASAN SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL WEST 8 1819-09183 ABAPO, DRANELLE KARL BENDER HOLY CHILD ACADEMY 84 1819-09040 ABERGAS, JOHN LLOYD BALAYONG SAINT COLUMBAN COLLEGE 9 1819-08610 ABAPO, RHEA MAE ALIPAN AURORA-ESU 85 1819-01682 ABIERA, NICCA ELA PADAWAN ATENEO DE ZAMBOANGA UNIVERSITY 10 1819-04583 ABASOLO, ROJIEN LAPOZ JOSE RIZAL MEMORIAL -

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

Wmsu College Entrance Test

WMSU COLLEGE ENTRANCE TEST November-December 2012 (SY 2013-2014) QUALIFIED TO ENROLL IN THE COLLEGE OF FORESTRY, AGRICULTURE& ESU's - (40.00%-49.99%ile) CLAIM YOUR INDIVIDUAL RESULT FROM YOUR SCHOOL CONTACT PERSON/GUIDANCE COUNSELOR OR FROM THE CONTACT PERSON AT THE EXTERNAL TEST CENTER WHERE YOU TOOK THE TEST No. Appno NAME SCHOOL No. Appno NAME SCHOOL 1. 1314-04947 ABAA, ROBIN CERILO WESTERN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY 75. 1314-04779 ALBERTO, ROSEMELYN FERNANDEZ VITALI NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 2. 1314-10047 ABANES, MARY JOY BERNALES ZAMBOANGA NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - WEST 76. 1314-08342 ALBERTO, VINCENT FRED VALLE ZAMBOANGA CITY HIGH SCHOOL 3. 1314-02574 ABBAS, SAIDAL LAGAM MSU - PREPARATORY HIGH SCHOOL 77. 1314-03691 ALBOR, MARK GIL CUSTODIO SIAY-ESU 4. 1314-10791 ABDUHASAN, ALMINDA SAGGAP ZAMBOANGA NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - WEST 78. 1314-04054 ALBOS, DESIREE ALEJANDRO LILOY NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 5. 1314-05517 ABDUL, JEHANA JAMANI ZAMBOANGA NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - WEST 79. 1314-11697 ALCANSADO, ELLEN ANTONETTE GATUNANCOGON NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 6. 1314-02927 ABDUL, JULHADZRI ABDUL ALICIA NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 80. 1314-09315 ALCUIZAR, KIRALEE BAUTISTA ZAMBOANGA CITY STATE POLYTECHNIC COLL 7. 1314-03016 ABDUL, MARRIZA ABDUL ALICIA - ESU 81. 1314-08449 ALDOHISA, CRISZEL MANULIS DON PABLO LORENZO MEMORIAL HIGH SCH. 8. 1314-10872 ABDUL, NAHLA AHMAD WESTERN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY 82. 1314-01384 ALEJABO, CAROLEEN IGNACIO BALIGUIAN NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 9. 1314-09918 ABDULA, FATRAMAR AMMAY J-JIREH SCHOOL 83. 1314-08103 ALEJANDRO, FLORENCE DOMINGO MARIA CLARA LOBREGAT NATIONAL HIGH SCH 10. 1314-00837 ABDULKARIM, NUR AINI SANDONG ZAMBOANGA CITY ALLIANCE EVANGELICAL S 84. 1314-04838 ALEJANDRO, HAZEL MANINGO VITALI NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 11. -

The Purok System for Efficient Delivery of Basic Services and Community Development”

“UTILIZING THE PUROK SYSTEM FOR EFFICIENT DELIVERY OF BASIC SERVICES AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT” “OUR WAY IN SAN FRANCISCO” OUR VISION “A PLACE TO LIVE, THE PLACE TO VISIT.” The Purok System – How did it start ? HEALTH & NUTRITION AGRICULTURE & LIVELIHOOD SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT DISASTER RISK REDUCTION & MANAGEMENT / ? /ENVIRONMENTAL PUROK READING OUR CENTER - 1953 TOURISM & WOMEN CHALLENGE & CHILDREN ONLY ABOUT EDUCATION Organized by – DepEd INFRASTRUCTURE Focused on Education Literacy Classes YOUTH & SPORTS DEVELOPMENT The Purok System – How was it energized? HEALTH & NUTRITION AGRICULTURE & LIVELIHOOD EDUCATION & SOLID WASTE MNGT. PEACE & ORDER / DRR/Environment TOURISM & WOMEN PUROK HALL - 2004 & CHILDREN Adopted by - LGU INFRASTRUCTURE YOUTH & SPORTS DEVELOPMENT HOW WE ORGANIZE OURSELVES ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE MUNICIPAL MAYOR CHAIRMAN SUPERVISOR OVERALL COORDINATOR PUROK PUROK PUROK PUROK PUROK PUROK COORDINATOR COORDINATOR COORDINATOR COORDINATOR COORDINATOR COORDINATOR NORTH DISTRICT NORTH DISTRICT CENTRAL DISTRICT CENTRAL DISTRICT SOUTH DISTRICT SOUTH DISTRICT 21 Puroks 21 Puroks 18 Puroks 19 Puroks 21 Puroks 20 Puroks PUROK ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE NAME OF BARANGAY BARANGAY CAPTAIN BARANGAY HALL NAME OF SITIO BARANGAY KAGAWAD PUROK HALL NAME OF PUROK PUROK PRESIDENT SET OF OFFICERS PUROK PUROK PUROK PUROK PUROK PUROK PUROK KAGAWAD KAGAWAD KAGAWAD KAGAWAD KAGAWAD KAGAWAD PUROK KAGAWAD KAGAWAD COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE ON ON ON ON ON ON DISASTER COMMITTEE ON EDUC. & TOURISM & YOUTH & HEALTH & AGRICULTURE RISK ON FINANCE, SOLID WASTE REDUDCTION WOMEN/ INFRASTRUCTURE SPORTS BUDGET& NUTRITION & LIVELIHOOD MNGT. / ENVIRONMENT CHILDREN DEV’T APPROPRIATION HOW A PUROK SYSTEM WORKS? Election Purok Meeting and General Assembly Weekly Meeting of Purok Coordinators RESULTS AND OUTCOMES OF OUR INITIATIVES Efficient delivery of the LGU and NGO - led programs and services: Satisfied and Happy Communities. -

Zamboanga City: a Case Study of Forced Migration

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Case Study of Zamboanga City (Forced Migration Area) Ma. Luisa D. Barrios-Fabian DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2004-50 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. December 2004 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph RESEARCH REPORT CASE STUDY OF ZAMBOANGA CITY (FORCED MIGRATION AREA) Undertaken through the POPCOM-PIDS Population, Urbanization and Local Governance Project MA. LUISA D. BARRIOS-FABIAN Research Consultant MA. LUISA D. BARRIOS-FABIAN Research Consultant ABSTRACT OF THE STUDY Background and Objectives of the Study: In the City of Zamboanga, the increase in growth rate during the first half of the decade (1990-1995) can be attributed to the net migration rate. This plus the rapid urbanization, has brought about positive and negative results, particularly on service delivery, resource mobilization and social concerns. -

No. Reference No. Item Description Location Winning Bidder Name and Address Bid Amount Bidding Date for Contract (Calendar Days) MANSUETO S

FDP Form 10a- Bid Results on Civil Works Republic of the Philippines CIVIL WORKS BID-OUT Province, City or Municipality: ZAMBOANGA CITY SECOND QUARTER 2018 Contract Approved Budget Duration No. Reference No. Item Description Location Winning Bidder Name and Address Bid Amount Bidding Date for Contract (Calendar Days) MANSUETO S. BENITOY, Purok 2, Construction/Rehabilitation/Improvement of Water 1 CW -18-0509-040 1,378,000.00 San Roque EMMB Construction & Supplies Cabaluay, 1294.927.82 May 29, 2018 75 System at Slaughterhouse, San Roque Zamboanga City Repair and Maintenance of Flood Controls ABSOLUTE Engineering and Engr. Nonelito W. Baring, 057 MCLL 2 CW -18-0509-038 10,000,000.00 Tugbungan 9,998,768.13 May 29, 2018 122 (Dredging of River) at Tugbungan Supplies Highway Divisoria, Zamboanga City Construction/Rehabilitation/Improvement of Road ABSOLUTE Engineering and Engr. Nonelito W. Baring, 057 MCLL 3 CW -18-0316-037 29,439,000.00 Kasanyangan 27376.563.81 May 29, 2018 370 for Tetuan-Kasanyangan Road Supplies Highway Divisoria, Zamboanga City Rehabilitation of Tetuan Main Road (Junction ABSOLUTE Engineering and Engr. Nonelito W. Baring, 057 MCLL 4 CW -18-0316-037 9,790,000.00 Tetuan 9,781,418.32 June 26, 2018 108 Falcatan St- Junction C. Atilano St.), Tetuan Supplies Highway Divisoria, Zamboanga City KARIM A. MOHAMMAD, Blk.3 Lot 10, HB 5 CW -18-0316-034 Rehabilitation of Sta. Catalina-Kasanyangan Road 7,100,000.00 Kasanyangan C.L.A Construction Homes Subd., Sinunuc, 7,092,771.14 June 26, 2018 85 Zamboanga City Construction of One (1) Storey Two (2) Classroom E.G. -

Protection Orders Under Republic Act 9262, Otherwise Known As the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act

PROTECTION ORDERS UNDER REPUBLIC ACT 9262, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE ANTI-VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND THEIR CHILDREN ACT …….. Sec. 8. Protection Orders.- A protection order is an order issued under this act for the purpose of preventing further acts of violence against a woman or her child specified in Section 5 of this Act and granting other necessary relief. The reliefs granted under a protection order serve the purpose of safeguarding the victim from further harm, minimizing any disruption in the victim's daily life, and facilitating the opportunity and ability of the victim to independently regain control over her life. The provisions of the protection order shall be enforced by law enforcement agencies. The protection orders that may be issued under this Act are the barangay protection order (BPO), temporary protection order (TPO) and permanent protection order (PPO). The protection orders that may be issued under this Act shall include any, some or all of the following reliefs: (a) Prohibition of the respondent from threatening to commit or committing, personally or through another, any of the acts mentioned in Section 5 of this Act; (b) Prohibition of the respondent from harassing, annoying, telephoning, contacting or otherwise communicating with the petitioner, directly or indirectly; (c) Removal and exclusion of the respondent from the residence of the petitioner, regardless of ownership of the residence, either temporarily for the purpose of protecting the petitioner, or permanently where no property rights are violated, and if -

PHL-OCHA-Zambo City 3W 25Oct2013

Philippines: Zamboanga Emergency Who-does What Where (3W) as of 25 October 2013 Interventions/Activities Lumbangan SCI Boy Scout Camp Lumbangan ES SCI Camp NDR, WHO UNFPA/FPOP, WHO Pasobolong Elementary School (Closed) Pasabulong ES ! Pasobolong Culianan Community Lunzaran UNFPA/FPOP Taluksangay Capisan Pasonanca Dulian Salaan DOH-CHD SCI SCI Lumbangan Clusters SCI Food Security Lunzaran Hall Boalan ES Pasabolong Health incl. RH UNFPA/FPOP, DOH Maasin UNFPA/FPOP, DOH, PNP SCI Pasonanca ES WVI Protection incl. GBV and CP WVI, SCI SCI UNFPA/FPOP, NDR, ICRC/PRC WASH WHO ICRC/PRC, UNICEF WVI, SAC/CAPIN ICRC/PRC Education ICRC/PRC Logistics Lumbangan BH UNFPA/FPOP, WHO Shelter Taluksangay Nutrition Lunzuran Sta. Maria ES Taluksangay National High School Early Recovery UNFPA/FPOP, Cabatangan DPWH Compound (Closed) ICRC/PRC, WHO, CCCM Minda ! Talabaan ! Livelihood Health/USAID, NDR Boy Scout Camp (Closed) Lunzuran Barangay Hall WVI, UNFPA/FPOP ! ! Lumbangan Brgy. Hall IOM Divisoria ! Boalan Elementary School (Closed) ICRC/PRC Pasonanca ! Zamboanga City Boalan ! Mercedes Pasonanca Elementary School Divisoria Elementary School Taluksangay Bunk House WFP ! Sta. Maria San Roque ! ! Zambowood Elementary School (ZES) Malagutay SCI Mercedes ES Holy Trinity Parish (Closed) Zambowood! ICRC/PRC Divisoria National High School UNFPA/FPOP ! Divisoria ES UNFPA/FPOP, WHO, Tumaga DOH, NCMH, PNP, DepEd Al-Jahara Mosque Putik SCI Taluksangay ES UNFPA/FPOP La Ciudad Montessori School Archdiocese of ZC, UNFPA/FPOP, Merlin, Santa Maria DSWD, Guiwan, ICRC/PRC ! MEMPCO -

Zamboanga Peninsula Regional Development

Contents List of Tables ix List of Figures xv List of Acronyms Used xix Message of the Secretary of Socioeconomic Planning xxv Message of the Regional Development Council IX xxvi Chairperson for the period 2016-2019 Message of the Regional Development Council IX xxvii Chairperson Preface message of the National Economic and xxviii Development Authority IX Regional Director Politico-Administrative Map of Zamboanga Peninsula xxix Part I: Introduction Chapter 1: The Long View 3 Chapter 2: Global and Regional Trends and Prospects 7 Chapter 3: Overlay of Economic Growth, Demographic Trends, 11 and Physical Characteristics Chapter 4: The Zamboanga Peninsula Development Framework 27 Part II: Enhancing the Social Fabric (“Malasakit”) Chapter 5: Ensuring People-Centered, Clean and Efficient 41 Governance Chapter 6: Pursuing Swift and Fair Administration of Justice 55 Chapter 7: Promoting Philippine Culture and Values 67 Part III: Inequality-Reducing Transformation (“Pagbabago”) Chapter 8: Expanding Economic Opportunities in Agriculture, 81 Forestry, and Fisheries Chapter 9: Expanding Economic Opportunities in Industry and 95 Services Through Trabaho at Negosyo Chapter 10: Accelerating Human Capital Development 113 Chapter 11: Reducing Vulnerability of Individuals and Families 129 Chapter 12: Building Safe and Secure Communities 143 Part IV: Increasing Growth Potential (“Patuloy na Pag-unlad”) Chapter 13: Reaching for the Demographic Dividend 153 Part V: Enabling and Supportive Economic Environment Chapter 15: Ensuring Sound Macroeconomic Policy -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

Infrastructure

Republic of the Philippines City Government of Zamboanga BIDS AND AWARDS COMMITTEE Villalobos Street, Zone IV, Zamboanga City Tel. No. (062) 992-7763 INDICATIVE Annual Procurement Plan for FY 2021 INFRASTRUCTURE Schedule for Each Procurement Activity Estimated Budget (PhP) Remarks PMO/ Mode of Source of Code (PAP) Procurement Program/Project End- M Procurement Funds User Ads/Post of IB/REI Sub/Open of Bids Notice of Award Contract Signing Total O CO (brief OE description of Office: City Engineer Function: ES: Local Dev't Dev't Fund: Other Economic Services Projects (20% DF) Account: 100-8919-1 Fund: General Fund- Special Account OTHER LAND IMPROVEMENTS 1-07-02-990 Site Developments: FEBRUARY 1. Construction of Sanitary Landfill (Cell#3) at Salaan 100,000,000.00 100,000,000.00 Salaan Road Networks Farm-to-Market Roads: 1. Construction/Rehabilitation/Improvement of Taguiti 3,000,000.00 3,000,000.00 Farm-to-Market Road at Taguiti 2. Construction of Farm-to-Market Road at: 2.1 Tumitus Tumitus 3,000,000.00 3,000,000.00 2.2 Victoria Victoria 3,000,000.00 3,000,000.00 1-07-03-010 JANUARY 3. Construction/Rehabilitation/Improvement of Manalipa 3,000,000.00 3,000,000.00 Road at Manalipa Competitive GENERAL City Engineer FIRST QUARTER FIRST QUARTER FIRST QUARTER FIRST QUARTER 4. Rehabilitation/Improvement of Road at Lapakan Lapakan Bidding FUND 3,000,000.00 3,000,000.00 5. Rehabilitation/Improvement of Road leading to Cabaluay 1,000,000.00 1,000,000.00 Cabaluay National High School, Cabaluay Concreting of Roads: 6.