Interim Report to the 86Th Texas Legislature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

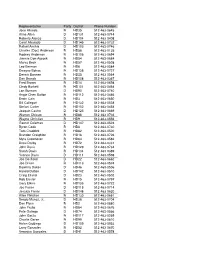

82Nd Leg Members

Representative Party District Phone Number Jose Aliseda R HD35 512-463-0645 Alma Allen D HD131 512-463-0744 Roberto Alonzo D HD104 512-463-0408 Carol Alvarado D HD145 512-463-0732 Rafael Anchia D HD103 512-463-0746 Charles (Doc) Anderson R HD56 512-463-0135 Rodney Anderson R HD106 512-463-0694 Jimmie Don Aycock R HD54 512-463-0684 Marva Beck R HD57 512-463-0508 Leo Berman R HD6 512-463-0584 Dwayne Bohac R HD138 512-463-0727 Dennis Bonnen R HD25 512-463-0564 Dan Branch R HD108 512-463-0367 Fred Brown R HD14 512-463-0698 Cindy Burkett R HD101 512-463-0464 Lon Burnam D HD90 512-463-0740 Angie Chen Button R HD112 512-463-0486 Erwin Cain R HD3 512-463-0650 Bill Callegari R HD132 512-463-0528 Stefani Carter R HD102 512-463-0454 Joaquin Castro D HD125 512-463-0669 Warren Chisum R HD88 512-463-0736 Wayne Christian R HD9 512-463-0556 Garnet Coleman D HD147 512-463-0524 Byron Cook R HD8 512-463-0730 Tom Craddick R HD82 512-463-0500 Brandon Creighton R HD16 512-463-0726 Myra Crownover R HD64 512-463-0582 Drew Darby R HD72 512-463-0331 John Davis R HD129 512-463-0734 Sarah Davis R HD134 512-463-0389 Yvonne Davis D HD111 512-463-0598 Joe Deshotel D HD22 512-463-0662 Joe Driver R HD113 512-463-0574 Dawnna Dukes D HD46 512-463-0506 Harold Dutton D HD142 512-463-0510 Craig Eiland D HD23 512-463-0502 Rob Eissler R HD15 512-463-0797 Gary Elkins R HD135 512-463-0722 Joe Farias D HD118 512-463-0714 Jessica Farrar D HD148 512-463-0620 Allen Fletcher R HD130 512-463-0661 Sergio Munoz, Jr. -

Joe Represents the 22Nd Legislative District, Which Includes Parts Of

Representative Joe Deshotel represents the 22nd Legislative District, which includes parts of Jefferson and Orange Counties. He is a successful attorney, businessman and life-long resident of Beaumont. At the end of his first Session, the Legislative Study Group (LSG), the largest caucus in the state, presented Representative Deshotel with the Rising Star Award. He was also elected Caucus Chairman by his colleagues in the Texas Legislative Black Caucus. In the 78th Legislative Session, Representative Deshotel served on the House Appropriations Committee, which is the budget writing arm of the House. He also served as the Vice Chair of Local & Consent Calendars, Chairman of Budget Oversight (CBO) for the House Elections Committee, and on the Select Committee on State Health Care Expenditures. In the 79th Legislative Session, Representative Deshotel was appointed to the House Committees on Economic Development, Transportation, and Redistricting. Representative Deshotel's tenure on the House Committee on Economic Development has helped bring in much needed investment dollars to Southeast Texas. In the 80th Legislative Session, Representative Deshotel was appointed to serve as Chairman of the House Economic Development Committee. "Being named chairman of Economic Development Committee is important for East Texas," Deshotel said. "This committee assignment ensures that job creation and the increased vitalization of the local technology industry receive proper attention during the legislative process," Chairman Deshotel stated. In the 81st Legislative -

Legislative Staff: 86Th Legislature

HRO HOUSE RESEARCH ORGANIZATION Texas House of Representatives Legislative Staff 86th Legislature 2019 Focus Report No. 86-3 House Research Organization Page 2 Table of Contents House of Representatives ....................................3 House Committees ..............................................15 Senate ...................................................................18 Senate Committees .............................................22 Other State Numbers...........................................24 Cover design by Robert Inks House Research Organization Page 3 House of Representatives ALLEN, Alma A. GW.5 BELL, Cecil Jr. E2.708 Phone: (512) 463-0744 Phone: (512) 463-0650 Fax: (512) 463-0761 Fax: (512) 463-0575 Chief of staff ...........................................Anneliese Vogel Chief of staff .............................................. Ariane Marion Legislative director .....................................Jaime Puente Policy analyst ...........................................Clinton Harned Legislative aide....................................... Jennifer Russell Legislative aide.............................................Brian Aldaco ALLISON, Steve E1.512 BELL, Keith E2.702 Phone: (512) 463-0686 Phone: (512) 463-0458 Chief of staff .................................................Rocky Gage Fax: (512) 463-2040 Legislative director ...................................German Lopez Chief of staff .................................... Georgeanne Palmer Scheduler ...............................................Redding Mickler -

Congressional Record—House H4021

May 14, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H4021 stand, especially those heroes from CELEBRATING FUNNY CIDE’S RUN ate and the Texas House, I know the south Texas: Kino Flores, Jim Solis, (Mr. STEARNS asked and was given value that the 53 Texas Democrats who Rene Oliveira, Aaron Pena, Miguel permission to address the House for 1 are in Ardmore, Oklahoma, today place Wise, Ryan Guillen and Juan Escobar. minute.) on the proud tradition of placing prin- We support them. Mr. STEARNS. Mr. Speaker, I rise to ciple above partisanship. When the Re- applaud the accomplishments of a man publican leader of the Texas House f from my hometown in Marion County, agreed to the political handiwork of Florida, the Sixth Congressional Dis- the majority leader of the U.S. House, ARMED FORCES DAY trict, because Tony Everard has been he abandoned a tradition that has (Mr. SAM JOHNSON of Texas asked training horses in Marion County for served Texas well. and was given permission to address over 35 years. When Texas House Republicans drew the House for 1 minute and to revise He purchased a remarkable horse, a a redistricting map without public and extend his remarks.) gelding, in 2001 in Saratoga, New York, hearings, behind closed doors, a map Mr. SAM JOHNSON of Texas. This and he trained it, but on May 3, this handed to them by Washington, they weekend is Armed Forces Day, and are horse became champion at the pinnacle trampled on a tradition in Texas, and not our men and women in uniform of horse racing, the Kentucky Derby. -

IDEOLOGY and PARTISANSHIP in the 87Th (2021) REGULAR SESSION of the TEXAS LEGISLATURE

IDEOLOGY AND PARTISANSHIP IN THE 87th (2021) REGULAR SESSION OF THE TEXAS LEGISLATURE Mark P. Jones, Ph.D. Fellow in Political Science, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy July 2021 © 2021 Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute. Mark P. Jones, Ph.D. “Ideology and Partisanship in the 87th (2021) Regular Session of the Texas Legislature” https://doi.org/10.25613/HP57-BF70 Ideology and Partisanship in the 87th (2021) Regular Session of the Texas Legislature Executive Summary This report utilizes roll call vote data to improve our understanding of the ideological and partisan dynamics of the Texas Legislature’s 87th regular session. The first section examines the location of the members of the Texas Senate and of the Texas House on the liberal-conservative dimension along which legislative politics takes place in Austin. In both chambers, every Republican is more conservative than every Democrat and every Democrat is more liberal than every Republican. There does, however, exist substantial ideological diversity within the respective Democratic and Republican delegations in each chamber. The second section explores the extent to which each senator and each representative was on the winning side of the non-lopsided final passage votes (FPVs) on which they voted. -

TSTA-PAC 2018 Endorsements Primary Winners / Runoffs / Friendly Incumbents

TSTA-PAC 2018 Endorsements Primary Winners / Runoffs / Friendly Incumbents Ryan Guillen - Rio Grande City HD 31** Republican Texas Senate Eric Johnson - Dallas HD 100** Kel Seliger - Amarillo SD 31** Jarvis Johnson - Houston HD 139 Julie Johnson - Dallas HD 115 Texas House of Representatives Ina Minjarez -San Antonio HD 124 Steve Allison – San Antonio HD 121* René O. Oliveira - Brownsville HD 37* Ernest Bailes - Shepherd HD 18 Ron Reynolds - Missouri City HD 27** Keith Bell - Forney HD 4 Shawn Thierry - Houston HD 146** Travis Clardy - Nacogdoches HD 11 John Turner - Dallas HD 114 Scott Cosper - Killeen HD 54* Dan Flynn - Van HD 2 State Board of Education Charlie Geren - Fort Worth HD 99 Ruben Cortez, Jr. - Brownsville SBOE 2 Cody Harris - Palestine HD 8 Marisa B. Perez - San Antonio SBOE 3 Dan Huberty - Houston HD 127** Ken King - Canadian HD 88 General Election Early Endorsement Chris Paddie - Marshall HD 9** Texas Senate Four Price - Amarillo HD 87** Democratic John Raney - Bryan HD 14 Kirk Watson - Austin SD 14 J.D. Sheffield - Gatesville HD 59** Royce West - Dallas SD 23 Hugh Shine - Temple HD 55** Reggie Smith - Sherman HD 62 Texas House of Representatives Lynn Stucky - Sanger HD 64 Democratic Alma Allen - Houston HD 131 Rafael Anchia - Dallas HD 103 Democratic Lt. Governor Nicole Collier - Fort Worth HD 95 Mike Collier - Houston Jessica Farrar - Houston HD 148 Abel Herrero - Robstown HD 34 Texas Senate Gina Hinojosa - Austin HD 49 Beverly Powell - Tarrant SD 10 Donna Howard - Austin HD 48 Nathan Johnson - Dallas SD 16 Victoria Neave - Dallas HD 107 John Whitmire - Houston SD 15 Mary Ann Perez - Houston HD 144 Joseph C. -

Press Release District 131- Houston

1108 Lavaca St, Suite 110-PMB 171, Austin, TX 78701-2172 Texas Legislative Black Caucus Chair Helen Giddings District 109- Dallas 1st Vice Chair Nicole Collier District 95- Ft. Worth FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: David Feigen (512) 463-0953 Secretary July 20, 2016 [email protected] Toni Rose District 110- Dallas Treasurer Alma Allen Press Release District 131- Houston Parliamentarian Joe Deshotel State Rep. Helen Giddings Named Chair of Texas Legislative Black Caucus District 22- Beaumont The TLBC addresses issues African Americans face across the state of Texas General Counsel Harold Dutton, Jr. District 142- Houston Austin- State Representative Helen Giddings (Dallas) has been elected Chair of the Texas Legislative Black Caucus (TLBC). She released the following statement: "I am honored to have the confidence of my fellow African American legislators to lead the Texas Legislative Black Caucus during this critical time for our state. The talents and skills of every member of the TLBC will be utilized to develop an agenda that builds on past successes and confronts the challenges of today. We face difficult issues and a tough political climate. Working together with our constituents will make Texas a better place for African Americans and every Texas resident. We all want safe neighborhoods, decent housing, access to healthcare, jobs with livable wages, and the ability to obtain a quality education. The members of the TLBC are committed to working toward that vision." The new officer board consists of proven legislative leaders who will represent the TLBC during the 85th Legislative session: Chair: Rep. Helen Giddings 1st Vice Chair: Rep. -

Legislative Staff: 87Th Legislature

HRO HOUSE RESEARCH ORGANIZATION Texas House of Representatives Legislative Staff 87th Legislature 2021 Focus Report No. 87-2 House Research Organization Page 2 Table of Contents House of Representatives ....................................3 House Committees ..............................................15 Senate ...................................................................18 Senate Committees .............................................22 Other State Numbers...........................................24 Cover design by Robert Inks House Research Organization Page 3 House of Representatives ALLEN, Alma A. GW.5 BELL, Cecil Jr. E2.708 Phone: (512) 463-0744 Phone: (512) 463-0650 Fax: (512) 463-0761 Fax: (512) 463-0575 Chief of staff ...........................................Anneliese Vogel Chief of staff .............................................. Ariane Marion Legislative director ................................. Adoneca Fortier Legislative aide......................................Joshua Chandler Legislative aide.................................... Sarah Hutchinson BELL, Keith E2.414 ALLISON, Steve E1.512 Phone: (512) 463-0458 Phone: (512) 463-0686 Fax: (512) 463-2040 Chief of staff .................................................Rocky Gage Chief of staff .................................... Georgeanne Palmer Legislative director/scheduler ...................German Lopez Legislative director ....................................Reed Johnson Legislative aide........................................ Rebecca Brady ANCHÍA, Rafael 1N.5 -

Texas House of Representatives Contact Information - 2017 Representative District Email Address (512) Phone Alma A

Texas House of Representatives Contact Information - 2017 Representative District Email Address (512) Phone Alma A. Allen (D) 131 [email protected] (512) 463-0744 Roberto R. Alonzo (D) 104 [email protected] (512) 463-0408 Carol Alvarado (D) 145 [email protected] (512) 463-0732 Rafael Anchia (D) 103 [email protected] (512) 463-0746 Charles "Doc" Anderson (R) 56 [email protected] (512) 463-0135 Rodney Anderson (R) 105 [email protected] (512) 463-0641 Diana Arévalo (D) 116 [email protected] (512) 463-0616 Trent Ashby (R) 57 [email protected] (512) 463-0508 Ernest Bailes (R) 18 [email protected] (512) 463-0570 Cecil Bell (R) 3 [email protected] (512) 463-0650 Diego Bernal (D) 123 [email protected] (512) 463-0532 Kyle Biedermann (R) 73 [email protected] (512) 463-0325 César Blanco (D) 76 [email protected] (512) 463-0622 Dwayne Bohac (R) 138 [email protected] (512) 463-0727 Dennis H. Bonnen (R) 25 [email protected] (512) 463-0564 Greg Bonnen (R) 24 [email protected] (512) 463-0729 Cindy Burkett (R) 113 [email protected] (512) 463-0464 DeWayne Burns (R) 58 [email protected] (512) 463-0538 Dustin Burrows (R) 83 [email protected] (512) 463-0542 Angie Chen Button (R) 112 [email protected] (512) 463-0486 Briscoe Cain (R) 128 [email protected] (512) 463-0733 Terry Canales (D) 40 [email protected] (512) 463-0426 Giovanni Capriglione (R) 98 [email protected] (512) 463-0690 Travis Clardy (R) 11 [email protected] (512) 463-0592 Garnet Coleman (D) 147 [email protected] (512) 463-0524 Nicole Collier (D) 95 [email protected] (512) 463-0716 Byron C. -

GINA HINOJOSA DEMOCRAT Incumbent

2020 General Election FACEOFFWEBSITE BOOKLET OCCUPATION CONSULTANT MAJOR ENDORSEMENTS Proprietary Document, Please Share Appropriately 1 VOTERS, CANDIDATES, AND ELECTED OFFICIALS: It’s time to start gearing up for the General Election! In a year that has already seen huge numbers of voter turnout, even amid a pandemic, the Texas state election promises to be one for the history books. To help all Texans better understand the landscape of this November’s race, we have put together a high-level booklet of the candidates facing off for every elected state position. Within this booklet, you will find biographical informa- tion and quick facts about each candidate. It is our hope that you will find this information helpful leading up to, during, and after the election as you get to know your candidates and victorious elected officials better. If you have suggestions on how to improve this document or would like to make an addition or correction, please let us know at [email protected]. Best of luck to all of the candidates, David White CEO of Public Blueprint To Note: Biographical information was sourced directly from campaign websites and may have been edited for length. Endorsements will be updated as major trade associations and organizations make their general election choices. "Unknown Consultant" denotes that we did not find a political consultant listed in expenditures on campaign finance reports. PUBLIC BLUEPRINT • 807 Brazos St, Suite 207 • Austin, TX 78701 [email protected] • publicblueprint.com • @publicblueprint TABLE OF CONTENTS 04. TEXAS SENATE CANDIDATES 32. TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES CANDIDATES 220. STATEWIDE CANDIDATES WEBSITE OCCUPATION CONSULTANT 3 TEXAS SENATE CANDIDATES FOR STATE SENATOR 06. -

Amicus Brief

FILED 21-0538 7/5/2021 4:10 PM tex-55047904 SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS BLAKE A. HAWTHORNE, CLERK No. 21-0538 In the Supreme Court of Texas IN RE CHRIS TURNER, IN HIS CAPACITY AS A MEMBER OF THE TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND HIS CAPACITY AS CHAIR OF THE HOUSE DEMOCRATIC CAUCUS, ET AL., Relators. On Petition for Writ of Mandamus TO GREGORY S. DAVIDSON, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS EXECUTIVE CLERK TO THE GOVERNOR, ET AL. BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF TEXAS Allison J. Riggs* Noor Taj* THE SOUTHERN COALITION FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE 1415 W. Hwy 54, Suite 101 Durham, NC 27707 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae * Application for admission pro hac vice pending Renea Hicks LAW OFFICE OF RENEA HICKS State Bar No. 09580400 P.O. Box 303187 Austin, Texas 78703-0504 (512) 480-8231 [email protected] IDENTITY OF PARTIES AND COUNSEL Legislative Member and Caucus Relators: House Democratic Caucus Mexican American Legislative Caucus Texas Legislative Black Caucus Legislative Study Group Alma Allen Rafael Anchía Michelle Beckley Diego Bernal Rhetta Bowers John Bucy Elizabeth Campos Terry Canales Sheryl Cole Garnet Coleman Nicole Collier Philip Cortez Jasmine Crockett Yvonne Davis Joe Deshotel Alex Dominguez Harold Dutton Jr. Art Fierro Barbara Gervin-Hawkins Jessica González Mary González Vikki Goodwin Bobby Guerra Ryan Guillen Ana Hernandez Gina Hinojosa Donna Howard Celia Israel Ann Johnson Jarvis Johnson i Julie Johnson Tracy King Oscar Longoria Ray Lopez Eddie Lucio III Armando Martinez Trey Martinez Fischer Terry Meza Ina Minjarez Joe Moody Christina Morales Eddie Morales Penny Morales Shaw Sergio Muñoz Jr. -

2014 Year End Report

1 Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2014 A Message from Craig Silliman Verizon is affected by a wide variety of government policies ‐‐ from telecommunications regulation to taxation to health care and more ‐‐ that have an enormous impact on the business climate in which we operate. We owe it to our shareowners, employees and customers to advocate public policies that will enable us to compete fairly and freely in the marketplace. Political contributions are one way we support the democratic electoral process and participate in the policy dialogue. Our employees have established political action committees at the federal level and in 18 states. These political action committees (PACs) allow employees to pool their resources to support candidates for office who generally support the public policies our employees advocate. This report lists all PAC contributions, corporate political contributions, support for ballot initiatives and independent expenditures made by Verizon during 2014. The contribution process is overseen by the Corporate Governance and Policy Committee of our Board of Directors, which receives a comprehensive report and briefing on these activities at least annually. We intend to update this voluntary disclosure twice a year and publish it on our corporate website. We believe this transparency with respect to our political spending is in keeping with our commitment to good corporate governance and a further sign of our responsiveness to the interests of our shareowners. Craig L. Silliman Executive Vice President, Public Policy and General Counsel 2 Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2014 Political Contributions Policy: Our Voice in the Political Process What are the Verizon Good Government Clubs? contributions process including the setting of The Verizon Good Government Clubs (GGCs) exist to monetary contribution limitations and the help the people of Verizon participate in America’s establishment of periodic reporting requirements.