Edelgive Foundation Annual Report 2018-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dual Edition

YEARS # 1 Indian American Weekly : Since 2006 VOL 15 ISSUE 20 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● MAY 14 - MAY 20, 2021 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● [email protected] www.theindianpanorama.news 12 OPPOSITION LEADERS WRITE TO PM MODI, US lifts most mask DEMANDING FREE MASS VACCINATION, guidance in key step back SUSPENSION OF CENTRAL VISTA PROJECT to post - Covid normalcy Fully vaccinated Americans can ditch their masks in most settings, even indoors or in large groups. WASHINGTON (TIP): President Joe Biden took his biggest step yet toward declaring a victory over the coronavirus pandemic - as public health officials said fully vaccinated Americans can ditch their masks in most settings, even indoors or in large groups. "Today is a great day for America in our long battle with coronavirus," Biden said in the In a joint letter to PM Modi, 12 opposition White House Rose Garden on Thursday,May 13, party leaders, including Sonia Gandhi, have demanded Central govt to provide calling the US vaccination program an foodgrains to the needy and Rs 6,000 "historical logistical achievement." monthly to the unemployed. - File photo of The guidance shift Thursday, May 13, is a Prime Minister Narendra Modi | Twitter turning point in the fight against Covid-19 and @BJP4India comes as US caseloads fall and vaccinations NEW DELHI (TIP): In a joint letter rise. It signals a broad return to everyday to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, lifeand is also a bet that any surge in spread May 12, 12 Opposition parties have from relaxed guidelines won't be enough to urged the government to immediately reverse progress in inoculations. -

One Year of COVID-19 Are We Seeing Shifts in Internal Migration Patterns in India?

Voices of the Invisible Citizens II One year of COVID-19 Are we seeing shifts in internal migration patterns in India? Voices of the Invisible Citizens II 1 Migrants Resilience Collaborative June 2021 2B, Jangpura B-Block, Mathura Road, New Delhi: 110014 Tel: 011-43628209 Email id: [email protected] www.jansahasindia.org Conceptualization and Research Design: Ashif Shaikh and Aarya Venugopal Principal Authors: Aarya Venugopal and Parvathy J Other Authors: Evlyn Samuel and Ameena Kidwai Design: Nikhil KC Cover page photograph: Ashish Ramesh Back cover page photograph: Sumit Singh Data collection team: Banda: Gautam, Md. Danish Khan, Sarita Shukla and Seema Devi; Delhi: Anjali Sharma, Arun Kumar, Geetanjali and Kamal Kumar; Hazaribagh: Anand Kumar, Jarina Khatun, Reeta Devi and Soni Kushwaha; Hyderabad: Brahmam, Prashanth. Sandeep and Vijay; Mahbubnagar: Amjad Hussain, Basheer and Bhaskar Reddy; Mumbai: Komal Ubale, Nikhil Wede, Rekha Abhang and Yojana Manjalkar; Tikamgarh: Priyanka Ahirwar, Rajesh Vanshkar, Rekha Raikwar, Brajesh Ahirwar Thanks for the valuable feedback, and efforts in coordination and training: Garima S, Vriti S, Nitish Narain, Arpita Sarkar, Varun Behani, Garima Dhiman, V S Daniel, Vishal Jairam, Akshay Mere, Dhirendra Kumar and others. Photo Credit: Dhiraj Singh/UNDP India Dhiraj Credit: Photo 2 Voices of the Invisible Citizens II Voices of the Invisible Citizens II One year of COVID-19 Are we seeing shifts in internal migration patterns in India? Preface When Jan Sahas released the report “Voices of the Invisible Citizens” in April 2020, about the mass exodus of migrant workers from cities, we thought we were witnessing and documenting one of the worst human tragedies in recent history. -

“Manual Scavenging: Worst Surviving Symbol of Untouchability” Rohini Dahiya1 Department of Political Science, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar Central University, Lucknow

Volume 10, May 2020 ISSN 2581-5504 “Manual Scavenging: Worst Surviving Symbol of Untouchability” Rohini Dahiya1 Department of Political Science, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar Central University, Lucknow “For them I am a sweeper, sweeper- untouchable! Untouchable! Untouchable! That’s the word! Untouchable! I am an Untouchable – Mulk Raj Anand, Untouchable (1935) Mulk Raj Anand while writing his book more than 80 years ago criticised the rigidity of the caste system and its ancient taboo on contamination. Focalising the six thousand years of racial and class superiority and predicament of untouchability with a desire to carry the perpetual discrimination faced by people living in the periphery out in the larger world. The hope with which the author, who was a key founder of the All-India Progressive writer’s movement wrote this breakthrough 1935 novel, still largely remains a hope, as the practices of manually cleaning excrement from private and public dry toilets, open drains, gutters, sewers still persist. Haunting lives of millions in a nation, which since its independence in 1947 adopted legislative and policy efforts to end manual scavenging. The practice of cleaning, carrying and disposing of human excreta from public streets, dry latrines, sceptic tanks and sewers using hand tools such as bucket, groom and shovel, is what is described as manual scavenging by International Labour Organisation which is termed as one of the worst surviving symbols of untouchability. The work of dealing with human excrement manually might seem an anathema to most of the people around the world but it is the only source of livelihood to thousands living in India even today. -

Issn - 2349-6746 Issn -2349-6738 the Role of Non Governmental Organizations in Promoting Sustainable Development

Research Paper Impact Factor: 5.646 IJMSRR Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal E- ISSN - 2349-6746 www.ijmsrr.com ISSN -2349-6738 THE ROLE OF NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS IN PROMOTING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Dr. Kanchana Naidu* Dr.Kalpana Naidu* *Asst. Professor,Women’s Chrstian College,Chennai Abstract Sustainable development is a way of using resources without the resources running out for future generations. This development is a multidimensional process and cannot be created by Govt. independently. Other stakeholders are also required to contribute effectively towards enhancing sustainability. The present paper highlights the importance & role of NGOs in promoting sustainable development in India. Introduction Sustainability means meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Sustainable Development is the organizing principle for meeting human development goals while simultaneously sustaining the ability of natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services upon which the economy and society depend. The desired result is a state of society where living conditions and resources are used to continue to meet human needs without undermining the integrity and stability of the natural system. It enables to attain a balance between environmental protection and human economic development and between the present and future needs. Sustainable Development implies development of four aspects viz Human, Social, Economic and Environmental. Human Sustainability refers to overall development of human capital by providing proper health, education, skills, knowledge, leadership and access to essential services. Social Sustainability is maintenance of social capital by focusing on investments and services that create the basic framework for society. -

List of Registered Ngos

LIST OF REGISTERED NGOS Name of the NGO Cause Website Contact Details FCRA Able Disabled All ADAPT endeavours to provide equal opportunities to disabled people People especially in the field of education and employment. The society also Dr.Anita Prabhu Together(Formerly conducts awareness programs about rights of the disabled, provides www.adaptssi.org 9820588314 Yes The Spastics therapy services to them and empowers mothers of disabled children [email protected] Society of India) by providing education and training for income generation. Amcha Ghar, a home for girls is dedicated to helpless female children - irrespective of their religion or caste- who are susceptible to the Susheela Singh vulnerable conditions of living on the street. The home aims to educate Amcha Ghar www.amchaghar.org 9892270729 Yes the girls in an English medium school, to train and transform them into amchaghar2yahoo.com skilled adult women who are able to live an independent life in the main stream of society. AAA aims to be the premier non-profit global body that represents & promotes the interests of individuals who have studied in the United Yasmin Shaikh States of America & those who wish to study in the United States of American Alumni 9987156303 America. It provides thought leadership in the area of educational, www.americanalumni.net Association american.alumni.association cultural and economic ties between India and the U.S. It includes many @gmail.com prominent members from the Indian Industries, Trade and Commerce and Multinational companies. An independent registered trust in India that provides immediate Chadrakant Deshpande AmeriCares India response to emergency medical needs and supports long-term www.americaresindia.org 9920692629 Foundation humanitarian assistance programs in India and in neighbouring [email protected] countries, irrespective of race, creed or political persuasion. -

The Tremendous Role of Non-Government Organizations in Lockdown Situation of India

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue 8 Ser. II || August 2020 || PP 11-19 The Tremendous Role of Non-Government Organizations in Lockdown Situation of India ShamsherRahaman Assistant Professor, Department of History, VidyasagarMahavidyalaya, University of Calcutta ABSTRACT:Non-Governmental Organizations are still playing a very important role to keep the society safe, generating awareness and development throughout lockdown India. In the eye of the rising COVID-19 storm, non-government organizations, big and small, are performing a massive task. The novel coronavirus lockdown has comfortably cooped most of us at house but marginalized communities in the unorganized sector, such as daily laborers, construction workers, street vendors and people involved in the cottage industry are terribly affected by the economic and social reflection of lockdown. NGOs coming forward to support the migrant workers and to fight the pandemic and provided food, water and transportation at their cost. In this paper I briefly analyze the role and contribution of NGOs (first half of 2020) in the lockdown situation of India. In this situation NGOs become unassuming heroes because they help fill in the gaps that governments often neglect and sprung into action to fill in gaps of communication and delivery of essential items to poor underserved communities. KEYWORDS: Pandemic, NGOs, combat against COVID-19, unassuming heroes, marginalized communities ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 28-07-2020 Date of Acceptance: 11-08-2020 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ --------------- I. INTRODUCTION The novel coronavirus (Covid-19) has now spread to almost all countries of the world as an epidemic. -

EDGE 2019 Greetings from Edelgive Foundation!

EDGE 2019 Greetings from EdelGive Foundation! As this edition of EDGE 2019 comes to a close we feel enriched, inspired and humbled by the conversations surrounding ‘The Power of One’. It was a day of thought, of reflection and of seeding a piece of inspiration to all participants in a small way. Like every year, EDGE has been designed as a collaborative platform to connect the funding fraternity with exceptional grassroots organisations. Revisiting these stories, below is a synopsis of the three-day conference and some key learnings that we took away from the deliberations. Day 1 – The Power of One Date: Wednesday, 13th November 2019 Venue: The St Regis Hotel, Mumbai Beginning the day with The Power of Voice, was our CEO, Vidya Shah. "Voice is an incredibly powerful tool in social change. Poets, authors, artists, even stand-up comedians have used it as a tool against injustice”, she said, as she took the audience through the role that ‘voice’ has played in shaping identity, defying social stigmas and creating powerful movements. Weaving together her favourite couplets, ghazals and poetry from legendary artists such as Ghulam Ali, Sahir Ludhianvi and Naseer Turabi, each verse symbolised a reaction to a moment in time, to an injustice and to a deep realisation of reality. Vidya Shah, CEO, EdelGive Foundation on ‘The Power of Voice’ The day was structured into five broad areas of discussion, Entrepreneurship – A Driver for Change, Vision – The Main Catalyst, Audacity in Belief, Representing the Unrepresented and Emotions Driving Change. Each packed with inspirational stories of individuals, organisations and movements. -

UNIT:3 Water Purification, Process by Which Undesired Chemical

UNIT:3 Water purification, process by which undesired chemical compounds, organic and inorganic materials, and biological contaminants are removed from water. That process also includes distillation (the conversion of a liquid into vapour to condense it back to liquid form) and deionization (ion removal through the extraction of dissolved salts). One major purpose of water purification is to provide clean drinking water. Water purification also meets the needs of medical, pharmacological, chemical, and industrial applications for clean and potable water. The purification procedure reduces the concentration of contaminants such as suspended particles, parasites, bacteria, algae, viruses, and fungi. Water purification takes place on scales from the large (e.g., for an entire city) to the small (e.g., for individual households). Water from inlets located in the water supply, such as a lake, is sent to be mixed, coagulated, and flocculated and is then sent to the waterworks for purification by filtering and chemical treatment. After being treated it is pumped into water mains for storage or distribution. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Water from inlets located in the water supply, such as a lake, is sent to be mixed, coagulated, and flocculated and is then sent to the waterworks for purification by filtering and chemical treatment. After being treated it is pumped into water mains for storage or distribution. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. from artesian wells was historically considered clean for all practical purposes, but it came under scrutiny during the first decade of the 21st century because of worries over pesticides, fertilizers, and other chemicals from the surface entering wells. As a result, artesian wells were subjected to treatment and batteries of tests, including tests for the parasite Cryptosporidium. -

2019 Forum Report December 10 - 12, 2019 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

2019 Forum Report December 10 - 12, 2019 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia www.freedomfromslaveryforum.org Special Thanks to our 2019 Forum Sponsors U.S. Department of Labor Support of the International Labor Organization and Alliance 8.7 2019 Forum Advisory Committee Willy Buloso | ECPAT International | Kenya Davina Durgana | Minderoo Foundation Walk Free Initiative | Australia Purva Gupta | Global March Against Child Labor | India Mara Vanderslice Kelly | United Way Worldwide | United States of America Dan Vexler and Daniel Melese | Freedom Fund | United Kingdom & Ethiopia Bukeni Waruzi | Free the Slaves | United States of America 2019 Forum Team Forum Managers: Allie Gardner, Terry FitzPatrick Forum Facilitator: Jost Wagner | The Change Initiative Report Production Assistance: Julia Grifferty Event Logistics: Eshi Events, Addis Ababa Forum Secretariat Free the Slaves 1320 19th St. NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20036, USA Phone +1.202.370.3625 Email: [email protected] Website: www.freedomfromslaveryforum.org Page 2 | 2019 Freedom from Slavery Forum Report Table of Contents Introduction and Summary 4 Theme One: Building an Agenda for Action 6 Theme Two: Researching the Cost to Eradicate Forced Labor & Modern Slavery 9 Theme Three: Learning from One Another 13 Evaluation 18 Participant List 19 Views expressed at the Forum and in this report are those of the participants and do not necessarily represent the views of the sponsoring organizations. Funding is provided by the United States Department of Labor under cooperative agreement number IL-30147-16-75-K-11. Approximately nine percent of this event has been funded by the Unites States Department of Labor for a total of USD 13,000. -

Feminist Research Studies

supporting women to challenge violence and negotiate equality feminist research studies perspective and capacity development on feminist principles and strategiesalliance building and networking supporting women’s leadership and agency annual report2018-19 1 JAGORI TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. PERSPECTIVE AND LEADERSHIP BUILDING ON WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND SAFETY 1 A. Feminist Leadership Development Course (FLDC) B. Feminist Counselling Workshop C. Need-based Sessions D. Community Leadership Development Programme (CLDP), Delhi E. Strengthening the Community Women’s Safety Forum (CWSF), Ranchi & Hazaribag F. Partnership with Pradan G. Gender Strategy Development Workshop H. Internship 2. ENABLING WOMEN SURVIVORS OF VIOLENCE 10 A. Crisis Intervention B. Survivor Support Groups C. Collective Interventions D. Interactions with Service Providers E. Internal Committee on Sexual Harassment at the Workplace 3. EXPANDING ENGAGEMENT ON WOMEN’S SAFETY 17 A. Collective Action for Women’s Safety in Delhi B. Creation of Safe Public Spaces for Women and Girls in Jharkhand 4. RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT 27 A. Research Studies B. Material Production C. Dissemination 5. NETWORKING AND JOINT ACTION 36 A. Campaigns B. Meetings/Consultations Organised/Co-organised by Jagori C. Partner Engagement 6. THE SANGAT PROJECT 45 A. Capacity Building B. Promotion of Feminist Culture, Information, Communication and Media C. Campaigns and Networking 7. INSTITUTION BUILDING 50 A. Organisational Matters B. Capacity Building of the Team C. Monitoring D. Governance Matters ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 FINANCIAL AUDIT 54 BOARD MEMBERS 56 PARTNERS 57 Jagori Annual Report 2018-2019 INTRODUCTION Much has changed in the discourse on women’s rights since Jagori came into being 34 years ago. During this period, Jagori has worked with marginalised women in urban and rural areas primarily on issues around violence against women, women’s rights, and their safety in public spaces. -

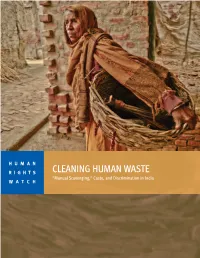

Manual Scavenging", Caste and Discrimination in India"

H U M A N R I G H T S CLEANING HUMAN WASTE “Manual Scavenging,” Caste, and Discrimination in India WATCH Cleaning Human Waste “Manual Scavenging,” Caste, and Discrimination in India Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1838 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2014 978-1-62313-1838 Cleaning Human Waste: “Manual Scavenging,” Caste, and Discrimination in India Glossary .............................................................................................................................. i Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

JICA India NGO Directory

JICA India NGO Directory S. NO. NAME OF ORGANISATION THEMATIC AREA OPERATIONAL STATE (S) CONTACT INFORMATION Tel: 9871100334 1 17000 Ft Foundation Education Jammu & Kashmir Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.17000ft.org Agriculture, Disaster Prevention, Education, Environment, Forestry, Tel: 9448370387 2 Abhivruddi Society For Social Development Health, Livelihood, Rural Development, Water, Sanitation & Hygiene, Karnataka Email: [email protected] Women Empowerment Website: http://www.abhivruddi.com Tel: 9801331700 Agriculture, Education, Health, Livelihood, Rural Development, Water, 3 Abhivyakti Foundation Jharkhand Email: [email protected] Sanitation & Hygiene, Women Empowerment Website: https://www.avfindia.org/ Tel: 9422702353 Education, Environment, Livelihood, Rural Development, Women 4 Abhivyakti Media For Development Maharashtra Email: [email protected] Empowerment Website: http://www.abhivyakti.org.in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Tel: 9769500292 5 Accion Technical Advisors India Education, Livelihood, Women Empowerment Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, Telangana, Uttarakhand, Email: [email protected] Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal Website: http://www.accion.org Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Chandigarh, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Goa, Gujarat, Tel: 9810410600 6 Action For Autism Education, Livelihood, Rural Development Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Punjab, Email: [email protected] Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh,