Grazing As a Conservation Management Tool in Peatland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rospuda Valley Survey 2007

Rospuda Valley Survey 2007 review of surveyed groups European species lists Biodiversity Survey final report - November 2008 Cite this report as: European Biodiversity Survey (): Biodiversity Survey Rospuda Valley, Final Report. Gronin- gen, European Biodiversity Survey. © European Biodiversity Survey (EBS). is is an open-access publication distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Photos on cover: top le corner: Nehallenia speciosa, by Tim Faasen. Middle right: Boloria eu- phrosyne, by Tim Faasen. Middle le: Colobochyla salicalis, by Wouter Moerland. Right bottom: Calcereous fen, by Bram Kuijper. European Biodiversity Survey Van Royenlaan A ES Groningen e-mail: info at biodiversitysurvey.eu www: www.biodiversitysurvey.eu is is not a eld guide. e Rospuda Vally and especially its valuable bogs are very vulnerable. ough more information on the distribution of species in the Rospuda Vally is important, please think twice before you enter the area. Contents Preface Introduction . Geography and natural history of the Rospuda area ................. . Pristine character ..................................... . ViaBaltica ......................................... . Vegetation zonation in the mire ............................. . Rationale for this survey ................................. . Methods .......................................... Aquatic fauna . Introduction ....................................... -

Conservation Grazing.Pdf

MINNESOTA WETLAND RESTORATION GUIDE CONSERVATION GRAZING TECHNICAL GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Document No.: WRG 6A-5 Publication Date: 1/30/2014 Table of Contents Introduction Application Other Considerations Costs Additional References INTRODUCTION Grazing by bison, elk and deer was historically a natural occurrence in grassland and shrubland plant communities in Minnesota. This grazing tended to be nomadic in nature and its intensity depended on the type of grazers, herd sizes, climate conditions, fire frequency, and the composition and structure of individual plant communities. Today conservation grazing is conducted by a variety of species including cattle, bison, horses, sheep, and goats to target specific invasive plants, or to replicate the grassland plant community structure and diversity that historically resulted from grazing. When grazing is conducted to control invasive species the intensity and duration of grazing is carefully monitored to ensure that target species are managed effectively, and that the integrity of the plant community is maintained. Most conservation grazing involves a short pulse of grazing followed by a long rest. Grazing can have benefits as well as negative impacts, so it is important to involve experienced professionals. Detailed grazing plans are an important component in the planning and implementation of prescribed grazing. Equipment that may be needed for grazing includes watering systems, electric, or barb”ed” wire fences around rotational grazing areas, moveable fencing to concentrate grazing and to ensure that areas are not overgrazed, and in some cases salt licks to concentrate animals (Tu et al. 2001). The following is a list of species commonly used for conservation grazing and their general characteristics. -

Management of Grazing Animals for Environmental Quality

Management of grazing animals for environmental quality Etienne M. in Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products Zaragoza : CIHEAM Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67 2005 pages 225-235 Article available on line / Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=6600046 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ To cite this article / Pour citer cet article -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ Etienne M. Management of grazing animals for environmental quality. In : Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products . Zaragoza : CIHEAM, 2005. p. 225-235 (Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://www.ciheam.org/ -

Kiss Diána IV

ЗАТВЕРДЖЕНО Вченою радою ЗУІ Протокол № „3” від „20” квітня 2017 р. Ф-КДМ-1 Міністерство освіти і науки України Закарпатський угорський інститут ім. Ференца Ракоці ІІ Кафедра біології та хімії Реєстраційний № _____________ Дипломна робота ФАУНІСТИЧНЕ ДОСЛІДЖЕННЯ ВИДІВ МЕТЕЛИКІВ (LEPIDOPTERA) С. ПАЛАДЬ КОМАРІВЦІ (УЖГОРОДСЬКИЙ РАЙОН) КІШ ДІАНА ЗОЛТАНІВНА Cтудентка IV-го курсу Cпеціальність: біологія Oсвітній рівень: бакалавр Тема затверджена на засіданні Кафедри біології та хімії Протокол № 2 від 10 жовтня 2019 р. Науковий керівник: Коложварі Степан Васильович доктор філософії, в/о доцента Завідувач Кафедрою біології та хімії: Когут Ержебет Імріївна доктор філософії з ботаніки, в/о доцента Робота захищена на оцінку ____________, „___” __________ 2020 р. Протокол № ______ / 2020 р. ЗАТВЕРДЖЕНО Вченою радою ЗУІ Протокол № „3” від „20” квітня 2017 р. Ф-КДМ-1 Міністерство освіти і науки України Закарпатський угорський інститут ім. Ференца Ракоці ІІ Кафедра біології та хімії Дипломна робота ФАУНІСТИЧНЕ ДОСЛІДЖЕННЯ ВИДІВ МЕТЕЛИКІВ (LEPIDOPTERA) С. ПАЛАДЬ КОМАРІВЦІ (УЖГОРОДСЬКИЙ РАЙОН) Виконавець: студентка ІV-го курсу спеціальність біологія освітній рівень: бакалавр Кіш Діана Золтанівна Науковий керівник: Коложварі Степан Васильович доктор філософії, в/о доцента Рецензент: Желіцкі І. Й. спец., ст. викладач Берегово 2020 ЗМІСТ ВСТУП ...................................................................................................................................... 6 І. ЛІТЕРАТУРНИЙ ОГЛЯД ................................................................................................. -

Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project Final Report

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project ATLAS ID GEF-00013971 TRAC-00013970 (formerly NEP/99/G35 and NEP/99/021) Final Report of the Terminal Evaluation Mission September 2006 Phillip Edwards (Team Leader) Rajendra Suwal Neeta Thapa ACRONYMS AND TERMS Exchange rate at the time of the TPE was US$1 to NR 71 (Nepali Rupees) ACA Anapurna Conservation Area ACAP Anapurna Conservation Area Project AHF American Himalayan Foundation APPA Appreciative Participatory Planning and Action BCP Biodiversity Conservation Plan CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAMOP Conservation Area Management Operation Plan CAMP Conservation Area Management Plan CAMR Conservation Area Management Regulation CBBMS Community Based Biodiversity Monitoring System CBO Community Based Organization CITES Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species CPM Co-Project Manager CRAC Community Resource Action Area Committee CRAJSC Community Resources Action Joint Sub-Committee CTF Community Trust Fund DAG Disadvantage Group DDC District Development Committee DNPWC Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation EIA Environment Impact Assessment FIT Free Independent Tourist/Trekker GEF Global Environment Facility GIS Geographic Information System GON Government of Nepal Ha. Hectares HMG His Majesty’s Government HQ Head Quarters HRD Human Resource Development ICDP Integrated Conservation Development Program ICIMOD International Center for Integrated Mountain Development IEA Initial Environmental Assessment IGA Income -

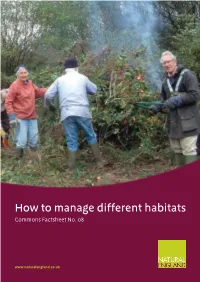

How to Manage Different Habitats Commons Factsheet No

How to manage different habitats Commons Factsheet No. 08 www.naturalengland.co.uk How to manage different habitats Many commons and greens are beautiful places, rich in wildlife. Because commons have a long history of being used by people, the habitats they support are relatively natural but have been shaped by human activities over the millennia (e.g. unimproved grassland, heathland, woodlands). If they are to retain their wildlife and scenery the traditional uses must either be continued, or replicated some other way (see FS3 Why does our common need to be looked after?). This factsheet summarises the characteristic features of each habitat type, together with conservation aims and management techniques for habitats frequently found on commons. Different techniques Before deciding on particular management techniques, you will want to consider their The management of habitats can vary from potential impact on the species present, simple to complex. It can often be carried the landscape, the environment, features out by volunteers with hand tools or may of archaeological and historical interest, need people with specialised training and and public access and safety (see FS5 Is our equipment. Here, the main methods you common more special than we think?, FS4 Who might use are outlined and sources of further has an interest in the common? and FS8 What information signposted. Herbicide treatments future for our commons?). Remember to plan are not discussed, as these are best used only aftercare and monitoring (see FS17 Are we if there are no other realistic options, and getting it right?). you will want specialist advice and possibly contractors to carry out the work. -

MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 Habitats * Semi-Natural Dry Grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210

Technical Report 2008 12/24 MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 habitats * Semi-natural dry grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210 The European Commission (DG ENV B2) commissioned the Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites) This document was prepared in March 2008 by Barbara Calaciura and Oliviero Spinelli, Comunità Ambiente Comments, data or general information were generously provided by: Bruna Comino, ERSAF Regione Lombardia, Italy Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Mats O.G. Eriksson, MK Natur- och Miljökonsult HB, Sweden Monika Janisova, Institute of Botany of Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovak Republic) Stefano Armiraglio, Museo di Scienze Naturali di Brescia, Italy Stefano Picchi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Guy Beaufoy, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Gwyn Jones, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Coordination: Concha Olmeda, ATECMA & Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente 2008 European Communities ISBN 978-92-79-08326-6 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Calaciura B & Spinelli O. 2008. Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites). European Commission This document, which has been prepared in the framework of a service contract (7030302/2006/453813/MAR/B2 "Natura 2000 preparatory actions: Management Models for Natura -

Bryn Tip Local Nature Reserve

BRYN TIP LOCAL NATURE RESERVE The village of Bryn is lucky enough to have its own Nature Reserve! The Reserve is popular with the residents of Bryn and visitors from further afield who come to walk their dogs, ride horses on the bridle way or take a gentle stroll whilst enjoying the wildlife and views of the surrounding countryside. The site has been used all year round and is also the starting point for the Bryn Heritage walk. This Reserve is home to hundreds of species of wildlife including flowers, fungi, invertebrates, birds, reptiles and mammals. The site was declared a Local Nature Reserve in order to protect the wildlife and preserve the landscape for people to enjoy long into the future. CONSERVATION GRAZING Over the last few years, the Countryside & Wildlife Team of the Local Authority have been working with contractors, and occasionally volunteers, to reduce the amount of invasive scrub on the site. This initial intensive management has allowed the grasses and flowering plants to flourish in those areas. However, unless the scrub is regularly managed it will become dense and eventually take over the grassland, making the site a lot less attractive to walk through. Similarly, the grassland is becoming rank and tussock and unless it is managed sensitively, much of the special wildlife will be lost. Using contractors and staff is not a sustainable long term approach for managing the Nature Reserve, even less so with the current and proposed budget cuts that the Local Authority is faced with. Conservation grazing is a more traditional, sustainable and less labour-intensive way of getting the grassland into good condition and keeping the scrub under control. -

New Records of Butterflies and Moths from the Czech Republic, and Update the Czech Lepidoptera Checklist Since 2011

Journal of the National Museum (Prague), Natural History Series Vol. 187 (2018), ISSN 1802-6842 (print), 1802-6850 (electronic) DOI: 10.2478/jnmpnhs-2018-0003 Původní práce / Original paper New records of butterflies and moths from the Czech Republic, and update the Czech Lepidoptera checklist since 2011 Jan Šumpich1* & Jan Liška2 1 Department of Entomology, National Museum, Cirkusová 1740, CZ-193 00 Praha 9 – Horní Počernice, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Forestry and Game Management Research Institute Jíloviště-Strnady, CZ-156 04 Praha 5 – Zbraslav, Czech Republic; [email protected] * corresponding author Šumpich J. & Liška J. 2018: New records of butterflies and moths from the Czech Republic, and update the Czech Lepidoptera checklist since 2011. – Journal of the National Museum (Prague), Natural History Series 187: 47–64. Abstract: Altogether four moth species, namely Agonopterix paraselini Buchner, 2017, A. medelichensis Buchner, 2015, Brachodes pumila (Ochsenheimer, 1808), and Callopistria latreillei (Duponchel, 1827) are reported from the Czech Republic for the first time. Coleophora aleramica Baldizzone & Stübner, 2007 is reported as a new species for Moravia, and Coleophora bilineatella Zeller, 1849, C. oriolella Zeller, 1849 and Syncopacma albifrontella (Heinemann, 1870) are new species for Bohemia. Historical record of Ischnoscia borreonella (Millière, 1874), unaccepted in previous checklists, is considered possible and included into the species list. Historical records of Plusidia cheiranthi (Tauscher, 1809) which were omitted in recent checklists are now considered reliable. The origin of Dorycnium herbaceum Vill. in Bohemia is commented on the basis of Lepidoptera trophically associated with this plant species. Keywords: Lepidoptera, Dorycnium herbaceum, new records, species list, Czech Republic, Europe, Palearctic Region Received: July 19, 2018 | Accepted: March 8, 2018 | Issued: December 31, 2018 Introduction - Concerning Lepidoptera, the Czech Republic belongs among best explored European coun tries. -

2014 Transformations Program

SUNY College Cortland Digital Commons @ Cortland Transformations College Archives 2014 2014 Transformations Program State University of New York at Cortland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/transformationsprograms Recommended Citation State University of New York at Cortland, "2014 Transformations Program" (2014). Transformations. 25. https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/transformationsprograms/25 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the College Archives at Digital Commons @ Cortland. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transformations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Cortland. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSFORMATIONS A Student Research and Creativity Conference April 25, 2014 Portland Transformations: A Student Research and Creativity Conference April 25, 2014 Sperry Center SUNY Cortland Schedule of Events 12:30-1:20 p.m. Keynote Address Sperry Center, Room 105 "Multidisciplinary Solutions to 2T Century Environmental Challenges: Lessons from Sustainable Agriculture and Conservation Grazing" Gary S. Kleppel 73, Ph.D. Professor of Biological Sciences; Director of Biodiversity, Conservation & Policy Program University of Albany 1:30-2:30 p.m. Concurrent Sessions I 2:30-3 p.m. Poster Session A Sperry Center, 1st Floor Hallway 3-4 p.m. Concurrent Sessions II 4-4:30 p.m. Poster Session B Sperry Center, 1st Floor Hallway 4:30-5:30 p.m. Concurrent Sessions III Refreshments will be available 2:30-4:30 p.m. in Sperry Center, first floor food service area. PLEASE NOTE: Food and beverages are NOT allowed in classrooms. Cover design by Lauren Abbott, New Media Design major. Transformations: A Student Research and Creativity Conference is an event designed to highlight and encourage scholarship among SUNY Cortland students. -

Data to the Knowledge of the Macrolepidoptera Fauna of the Sălaj-Region, Transylvania, Romania (Arthropoda: Insecta)

Studia Universitatis “Vasile Goldiş”, Seria Ştiinţele Vieţii Vol. 26 supplement 1, 2016, pp.59- 74 © 2016 Vasile Goldis University Press (www.studiauniversitatis.ro) DATA TO THE KNOWLEDGE OF THE MACROLEPIDOPTERA FAUNA OF THE SĂLAJ-REGION, TRANSYLVANIA, ROMANIA (ARTHROPODA: INSECTA) Zsolt BÁLINT*, Gergely KATONA, László RONKAY Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum ABSTRACT. We provide 984 data of 88 collecting events originating from the Sălaj-region of western Transylvania, Romania. These have been assembled in the period between 22. April, 2014 and 10. September, 2015. Geographical, spatial and temporal records to the knowledge of 98 butterflies (Papilionoidea) and 225 moths (Bombycoidea, Drepanoidea, Geometroidea, Noctuoidea and Sphingoidea) are given representing the families (species numbers in brackets) Hesperiidae (8), Lycaenidae (28), Nymphalidae (28), Papilionidae (3), Pieridae (13) Riodinidae (1), Satyridae (17) (Papilionoidea); Arctiidae (11), Ctenuchidae (1), Lymantriidae (1), Noctuidae (119), Nolidae (2), Notodontidae (6) Thyatiridae (4), (Noctuoidea); Drepanidae (3) (Drepanoidea); Geometridae (73) (Geometroidea); Lasiocampidae (2), Saturniidae (1) (Bombycoidea); Sphingidae (2) (Sphingoidea). According to the most recent catalogue of the Romanian Lepidoptera fauna 31 species proved to be new for the region Sălaj. The following 43 species have faunistical interest, therefore they are briefly annotated: Agrochola humilis, Agrochola laevis, Aplocera efformata, Aporophila lutulenta, Atethmia centrago, Bryoleuca -

Invasive Plants Established in the United States That Are Found in Asia and Their Associated Natural Enemies – Volume 2 Fungi Phylum Family Species H

Phragmites australis Common reed Introduction The genus Phragmites contains 10 species worldwide. Three members of the genus have been reported from China[123]. Species of Phragmites in China Scientific Name P. australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. P. japonica Steud, P. karka (Retz.) Trin. mm long and mostly bear 4-7 florets, therefore favored as cattle and horse which maybe male for the first one feed. As it matures, the lignified plant Taxonomy from the base. The glumes are 3- cannot be used as forage. However, Order: Graminales veined, 3-7 mm long for the first the mature culms can be used for Suborder: Gramineae glume and 5-11 mm for the second construction and paper making[58, Family: Gramineae (Poaceae) glume. The flowers appear from July 123]. Subfamily: Arundioideae to November[58, 68, 81, 84, 87, 123]. Tribe: Arundineae Related Species Subtribe: Arundinae Bews Habitat P. karka (Retz.) Trin. has comparatively Genus: Phragmites Trinius P. australis occurs at the edge of larger panicles and numerous spreading Species: Phragmites australis rivers, lakes, swamps, moist areas, branches. It occurs in Guangdong, (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. [=Phragmites and wetlands at lower elevations[58, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Sichuan, communis Trin.] 84, 123]. Taiwan and Yunnan provinces[123]. Description Distribution Natural Enemies of Phragmites Phragmites australis is a perennial P. australis has a nationwide distribution Twenty four species of fungi and grass with stoloniferous rhizomes. in China[123]. 117 species of arthropods have been The erect culm reaches a height recorded as associated with the genus of 8 m and a diameter of 1-4 cm.