What Makes Biological Organisation Teleological ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complexity, Information and Biological Organisation

Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems 3(2), 59-71, 2005 COMPLEXITY, INFORMATION AND BIOLOGICAL ORGANISATION Attila Grandpierre Konkoly Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Budapest, Hungary Conference paper Received: 15 September, 2005. Accepted: 15 October, 2005. SUMMARY Regarding the widespread confusion about the concept and nature of complexity, information and biological organization, we look for some coordinated conceptual considerations corresponding to quantitative measures suitable to grasp the main characteristics of biological complexity. Quantitative measures of algorithmic complexity of supercomputers like Blue Gene/L are compared with the complexity of the brain. We show that both the computer and the brain have a more fundamental, dynamic complexity measure corresponding to the number of operations per second. Recent insights suggest that the origin of complexity may go back to simplicity at a deeper level, corresponding to algorithmic complexity. We point out that for physical systems Ashby’s Law, Kahre’s Law and causal closure of the physical exclude the generation of information, and since genetic information corresponds to instructions, we are faced with a controversy telling that the algorithmic complexity of physics is 3 much lower than the instructions’ complexity of the human DNA: Ialgorithmic(physics) ~ 10 bit << 9 Iinstructions(DNA) ~ 10 bit. Analyzing the genetic complexity we obtain that actually the genetic information corresponds to a deeper than algorithmic level of complexity, putting an even greater emphasis to the information paradox. We show that the resolution of the fundamental information paradox may lie either in the chemical evolution of inheritance in abiogenesis, or in the existence of an autonomous biological principle allowing the production of information beyond physics. -

Computing Genomic Science: Bioinformatics and Standardisation in Proteomics

Computing Genomic Science: Bioinformatics and Standardisation in Proteomics by Jamie Lewis Cardiff University This thesis is submitted to the University of Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: U585242 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585242 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed:.. (candidate) Date:....................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ...................... (candidate) Date:....... ................................................ STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed.. A . Q w y l (candidate) Date:....... ................................................ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give my consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for the inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

Collection of Working Definitions 2012

APPENDIX I COLLECTION OF WORKING DEFINITIONS 2012 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Aims 3. Glossary 4. Identification of Missing Definitions 5. Conclusion 6. References 2 1. INTRODUCTION Over the past half decade, a variety of approaches have been proposed to incorporate mechanistic information into toxicity predictions. These initiatives have resulted in an assortment of terms coming into common use. Moreover, the increased usage of 21st Century toxicity testing, with a focus on advanced biological methods, has brought forward further terms. The resulting diverse set of terms and definitions has led to confusion among scientists and organisations. As a result, one of the conclusions and recommendations from the OECD Workshop on Using Mechanistic Information in Forming Chemical Categories was the development of a standardised set of terminology [1]. It was recognised that such a glossary would assist in the understanding of the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) concept as well as its recording, completion of the template and ultimate acceptance. Moreover, the use of a common ontology will also help to apply AOP concepts in developing (Q)SARs and chemical categories to advance the use of predictive techniques in assessments. 2. AIMS The purpose of this document is to collect definitions relevant to the AOP and general toxicity pathway concepts. To do this, the literature has been searched to find multiple definitions of terms relevant to AOPs. The ultimate goal would be to provide a harmonised set of definitions. It is appreciated, however, that such definitions may not be agreed in a formal sense, but would provide an illustration of the various terms. -

Organisational Closure in Biological Organisms Matteo Mossio, Alvaro Moreno

Organisational closure in biological organisms Matteo Mossio, Alvaro Moreno To cite this version: Matteo Mossio, Alvaro Moreno. Organisational closure in biological organisms. History and philoso- phy of Life Sciences, 2010, 32 (2-3), pp.269-288. halshs-00792436 HAL Id: halshs-00792436 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00792436 Submitted on 19 Sep 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Organisational closure in biological organisms Matteo Mossio & Alvaro Moreno Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science University of the Basque Country Avenida de Tolosa 70, 20080, San Sebastian, Spain Tel: +34-943018249 /Fax: +34-943015470 E.mail: [email protected] The central aim of this paper consists in arguing that biological organisms realize a specific kind of causal regime that we call “organisational closure”, i.e. a distinct level of causation, operating in addition to physical laws, generated by the action of material structures acting as constraints. We argue that organisational closure constitutes a fundamental property of biological systems since even its minimal instances are likely to possess at least some of the typical features of biological organisation, as exhibited by more complex organisms. -

Redalyc.REFLECTIONS on the ORIGIN of LIFE MORE THAN AN

Mètode Science Studies Journal ISSN: 2174-3487 [email protected] Universitat de València España Ruiz-Mirazo, Kepa; Moreno, Álvaro REFLECTIONS ON THE ORIGIN OF LIFE MORE THAN AN ‘EVOLUTIONARY’ PROBLEM Mètode Science Studies Journal, núm. 6, 2016, pp. 151-159 Universitat de València Valencia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=511754471022 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MONOGRAPH MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 6 (2016): 151–159. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.6.4997 ISSN: 2174-3487. Article received: 19/03/2015, accepted: 30/06/2015. REFLECTIONS ON THE ORIGIN OF LIFE MORE THAN AN ‘EVOLUTIONARY’ PROBLEM KEPA RUIZ-MIRAZO AND ÁLVARO MORENO This paper argues that the question of the origin of life cannot be explained by appealing exclusively to Darwinian evolutionary mechanisms, as many experts tend to assume, but requires a profound change in perspective. Accordingly, we highlight the fact that, in order to operate as a diversification force (and indirectly, a force for a potential increase in complexity), natural selection requires a number of conditions to be met in order for it to be possible: specifically, self-sustained and self-(re-)productive chemical organisation within a sufficiently large phenotypic space (that is, a wide range of functions). Therefore, we suggest an extension of the «self-organising» paradigm towards a «self-(re-)productive» one as an alternative to the main proposals regarding the origin of life, based on molecular populations (typically RNA) subject to Darwinian evolution. -

Incremental Identification of Qualitative Models of Biological

Journal of Machine Learning Research 9 (2008) 1475-1533 Submitted 5/06; Revised 10/07; Published 7/08 Incremental Identification of Qualitative Models of Biological Systems using Inductive Logic Programming Ashwin Srinivasan∗ [email protected] IBM India Research Laboratory 4-C, Institutional Area, Vasant Kunj Phase II New Delhi 110 070, India Ross D. King [email protected] Department of Computer Science University of Wales, Aberystwyth Ceredigion, Wales, UK Editor: Stefan Wrobel Abstract The use of computational models is increasingly expected to play an important role in predict- ing the behaviour of biological systems. Models are being sought at different scales of biological organisation namely: sub-cellular, cellular, tissue, organ, organism and ecosystem; with a view of identifying how different components are connected together, how they are controlled and how they behave when functioning as a system. Except for very simple biological processes, system iden- tification from first principles can be extremely difficult. This has brought into focus automated techniques for constructing models using data of system behaviour. Such techniques face three principal issues: (1) The model representation language must be rich enough to capture system be- haviour; (2) The system identification technique must be powerful enough to identify substantially complex models; and (3) There may not be sufficient data to obtain both the model’s structure and precise estimates of all of its parameters. In this paper, we address these issues in the following ways: (1) Models are represented in an expressive subset of first-order logic. Specifically, they are expressed as logic programs; (2) System identification is done using techniques developed in Inductive Logic Programming (ILP). -

Biological Organisation As Closure of Constraints$

Biological organisation as closure of constraintsI Maël Montévil1,2,∗, Matteo Mossio1,∗ IHPST - UMR 8590 13, rue du Four 75006 Paris Abstract We propose a conceptual and formal characterisation of biological organisation as a closure of constraints. We first establish a distinction between two causal regimes at work in biological systems: processes, which refer to the whole set of changes occurring in non-equilibrium open thermodynamic conditions; and constraints, those entities which, while acting upon the processes, exhibit some form of conservation (symmetry) at the relevant time scales. We then argue that, in biological systems, constraints realise closure, i.e. mutual dependence such that they both depend on and contribute to maintaining each other. With this characterisation in hand, we discuss how organisational closure can provide an operational tool for marking the boundaries between interacting biological systems. We conclude by focusing on the original conception of the relationship between stability and variation which emerges from this framework. Keywords: biological organisation, closure, constraints, symmetries, time scales 1. Introduction In Theoretical Biology, an enduring tradition has placed heavy emphasis on the idea that biological systems realise what could be referred to as “self-determination”. That is, in very general terms, the capacity of a system’s constitutive organisation to contribute to the determination and maintenance of its own conditions of existence through the effects of its activity (see also Mossio & Bich (2014), for more details). Usually (Weber & Varela, 2002), the origin of this tradition is traced back to the characterisation of biological systems as “self-organising”, as Kant proposed in his Critique of Judgement (Kant, 1790). -

Synthetic Glossary

Synthetic Glossary by Elena Giglio Entries or abbreviations Field, quality or measure Definition or short explanation Adaptive system Physics System able to modify itself and to define its proper domain of environmental pertaining perturbation, specifying the admissibility of the different environmental constraints Alliance Phytosociology Taxonomic level superior to association Allometry Forestry The quantitative relation between the size of a part and the whole in a series of related organisms differing in size Association Phytosociology Vegetational— or plant: a plant community presenting a defined floristic composition in relation to specific climatic and edaphic conditions. It represents a vegetation type having a taxonomic name with the Latin suffix—etum Attractor Mathematics A geometrical object towards which the trajectory of a dynamic system converges in the course of time Biological spectrum Ecology The whole of the hierarchic levels of life organisation on Earth. Approached by four different points of view, completely and unified by landscape bionomics Biomass, plant Ecology pB. The dry weight or the volume above ground of the individuals of a plant species population in a given area Bionomics Bionomics Synonymous of “biological-integrated ecology.” The study of the biological- environmental laws of Nature as a complex system of hyper-complex systems BTC Bionomics [Mcal/m2/year] Biological territorial capacity of vegetation. The flux of energy that a system dissipates to maintain its equilibrium state and its organisational level. Proportional to the state of metastability of the system BTC Classes Bionomics (I to IX) Nine standard ranges of BTC values, corresponding to different sets of vegetation formations, available to indicate the landscape structure and functions CBSt Bionomics Concise bionomic state of vegetation. -

The Great Ideas of Biology

n COLLEGELECTURES Thegreatideasofbiology SirPaulNurse ABSTRACT–Fourofthegreatideasofbiologyare matter.Biology’satomisthecell,whichisnotonly discussed:thecellasthebasicstructuralandfunc- thebasicstructuralunitofalllivingorganismsbutis tionalunitoflife,thegeneasthemechanismof alsothebasicfunctionalunitoflife.Thecelltheory heredity,evolutionbynaturalselection,andlifeas canbesummarisedasfollows:alllifeiscomposed chemistry.Afifthideaisexploredwherebybio- ofcells,andthecellisthesimplestunitexhibiting logicalorganisationisexplainedintermsoflogical thecharacteristicsoflife.Giventheimportanceof andinformationalprocessesandstructures. thisideaforunderstandingbiology,itisperhapssur- prisingthatithasnotcaughtthepublicimagination TheHarveian KEYWORDS:biochemistry,cell,evolution, morethanithas.Thismightbebecausetheideawas Orationisgiven fermentation,gene,history,hybridisation, annuallyatthe alongtimeindevelopment,takingnearly200years RoyalCollegeof information,organisation tobecomeproperlyformulated,andalsobecause Physiciansof thetheoryultimatelyrequiredtheeffortsofmany Londonunderan WilliamHarveywasnotonlyaneminentphysician, scientistsratherthanafewdominatingpersonalities, indentureof butalsoadistinguishedbiologist.Hewasoneofthe somaylackhumaninterest.Thehistoryofthisidea WilliamHarveyin firstexperimentalscientists,workingsomeyears isexcellentlyreviewedinHarris.1 1656.Thisarticle beforeGalileowhoisthescientistusuallycredited Thestoryofthecellbeginsin1665withRobert isbasedonthe withthisdistinction.SowithHarvey’sexampleas Hooke(1635–1703),experimentalisttothenewly -

Biological Organisation Unit Guide 2007/8

Biosciences Degree Programme Biological Organisation Unit Guide 2007/8 SMK-1-301 Teaching team: Alan Beeby (E227 – [email protected] – Unit leader) Anne-Maria Brennan (E2286 – [email protected]) This unit guide is designed to help you structure your learning by providing an indicative structure and content for the unit. It is a guide and not a definitive statement of what you will be taught. We will try to follow this published schedule as far as possible, but there may be some variation as the unit develops and as we try to match the pace and content of our teaching to student needs. Introduction This unit introduces you to current thinking on how biological systems are organised. It seeks to introduce the ways by which living systems are being investigated today. You will find this quite different from traditional approaches to teaching biology. A system consists of a number of elements which interact with each other and which persist together - cells, organisms, and populations are all systems. We are all familiar with the systems within a body - the circulatory system or the digestive system, for example - but systems work at all levels, from the subcellular to the ecosystem. A cell is a system comprising the nucleus, ribosomes, mitochondria and so on; a population is a system composed of individuals which together reproduce to increase their numbers. Communities comprise species that interact with each other within ecosystems. Most important are the interactions which keep a system together and organised. So, in this unit we will describe how the complex systems of an adult organism develop from a simple zygote. -

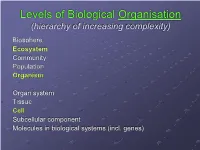

Levels of Biological Organisation (Hierarchy of Increasing Complexity) Biosphere Ecosystem Community Population Organism

Levels of Biological Organisation (hierarchy of increasing complexity) Biosphere Ecosystem Community Population Organism Organ system Tissue Cell Subcellular component Molecules in biological systems (incl. genes) Levels of Biological Integration Ecosystem Organism Cell The only true levels of integration in biology. True level: total environment of all levels below and a structural & functional component of next level above. Prediction at one level requires knowledge and consideration of next true level above. Forest Genetics: Pattern & Complexity Interacting set of ―species‖: if one forces a periodic or chaotic pattern by its own density dynamics, then all members of the set must develop responses to the interactive biotic environment. Forest–level pattern an emergent effect of independent, lower level elements; each population and species doing its own thing. Or pattern emerges as a consequence of strong functional interactions among the elements. Species assemblages not random associations – are selected, have +/- interactions supporting their existence Genes in individuals not random operators that happen to produce whole trees; they are assembled because they function together. Genes: Selfish or Environmentally Aware? All function derives from genes; higher levels of biological organisation ―mere outgrowths that carry gene effects‖? Gene effects emergent properties of molecular processes; also partly determined by developmental, population & ecosystem processes. No genotype without an environment ~ genotype defines environment. -

The Concept of Levels of Organization in the Biological Sciences

The Concept of Levels of Organization in the Biological Sciences PhD Thesis Submitted August 2014 Revised June 2015 Daniel Stephen Brooks Department of Philosophy Bielefeld University Reviewers: Martin Carrier, Maria Kronfeldner Dedicated in friendship to Jan and Magga “He who has suffer'd you to impose on him knows you.” Table of Contents Table of Contents........................................................................................................................1 Chapter One: The Intuitive Appeal and Ubiquity of 'Levels of Organization'............................5 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................5 1.2 Analyzing 'Levels of Organization' in Biological Science..........................................7 1.2.1 Level Claims.....................................................................................................10 1.2.2 Wimsatt’s Characterization of Levels ..............................................................14 1.3 Initial Distinctions.....................................................................................................16 1.3.1 Erroneous Concepts of Levels...........................................................................18 1.4 Depictions of Levels in Biological Textbooks...........................................................20 1.4.1 The Character of 'Levels' in Biological Science................................................24 1.4.2 The Significance of 'Levels' in Biological Science...........................................30