A Pidginization-Based Model of Transition Within the Built

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Make Plans to Attend the 2014 ONPA Convention at the Salem

spring/summer 2014 Make plans to attend the 2014 ONPA Convention at the Salem Convention Center Thursday-Friday, July 17-18 Register online at www.orenews.com To get a room in the ONPA block, contact the Grand Hotel at 1-877-540-7800 and be sure to mention the ONPA block to receive the discounted rates. THURSDAY, (Advertising Portion) July 17 7:30 a.m. – Registration table open 8-9 a.m. Breakfast – Introductions and discussion on challenges and successes at your paper 9-11:30 a.m. – Mike Blinder Session - Being Your Best on Every Sales Call! Mike Blinder President/ Founder of the Blinder Group is internationally recognized as an expert at media advertising. He will feature content from his Client 1st Training System that outlines the steps you need to take to prep for every single advertiser engagement. And, the attitude, style and traits you need to adapt into your selling style that ensures you get in the door and close more deals! Topics that will be covered in these fast paced sessions, will include: * Getting Beyond the Rejection * Blinder “Best Bets” to Target for New Business * Goals/ System for Effective Prospecting (Phone or face-to-face) * Making 1st Contact to Gain a 1st Appointment * Proper Call Prep (Doing Your Homework Before Your 1st Meeting) * Building the Right Rapport with Your Customers * Adjusting Your Rapport (and Theirs) to Gain Their Trust Noon – 1 p.m. Best Ad Ideas Awards Luncheon 1:15-2:30 p.m. Best Revenue Idea Sharing Session 2014 - The Best Just Got Better The Best Ad Idea Sharing session, is back with a twist. -

2019 Annual Directory 1 Our Readers Enjoy Many Oregon Newspaper Platform Options to Get Their Publishers Association Local News

2019 ANNUAL DIRECTORY 1 Our readers enjoy many OREGON NEWSPAPER platform options to get their PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION local news. This year’s cover was designed by 2019 Sherry Alexis www.sterryenterprises.com ANNUAL DIRECTORY Oregon Newspaper Publishers Association Real Acces Media Placement Publisher: Laurie Hieb Oregon Newspapers Foundation 4000 Kruse Way Place, Bld 2, STE 160 Portland OR 97035 • 503-624-6397 Fax 503-639-9009 Email: [email protected] Web: www.orenews.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 2018 ONPA and ONF directors 4 Who to call at ONPA 4 ONPA past presidents and directors 5 About ONPA 6 Map of General Member newspapers 7 General Member newspapers by owner 8 ONPA General Member newspapers 8 Daily/Multi-Weekly 12 Weekly 24 Member newspapers by county 25 ONPA Associate Member publications 27 ONPA Collegiate Member newspapers 28 Regional and National Associations 29 Newspaper Association of Idaho 30 Daily/Multi-Weekly 30 Weekly 33 Washington Newspaper Publishers Assoc. 34 Daily/Multi-Weekly 34 Weekly Return TOC 2018-19 BOARDS OF DIRECTORS Oregon Newspaper Publishers Association PRESIDENT president-elect IMMEDIATE PAST DIRECTOR PRESIDENT Joe Petshow Lyndon Zaitz Scott Olson Hood River News Keizertimes Mike McInally The Creswell Corvallis Gazette Chronical Times DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR John Maher Julianne H. Tim Smith Scott Swanson Newton The Oregonian, The News Review The New Era, Portland Ph.D., University of Sweet Home Oregon Roseburg DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR Chelsea Marr Emily Mentzer Nikki DeBuse Jeff Precourt The Dalles Chronicle Itemizer-Observer The World, Coos Bay Forest Grove News / Gazette-Times, Dallas Times - Hillsboro Corvallis / Democrat- Tribune Herald, Albany Oregon Newspapers Foundation DIRECTOR DIRECTOR PRESIDENT TREASURER Mike McInally Therese Joe Petshow James R. -

Sports and Recreational Tourism Spring/Summer

Sports and Recreational Tourism Spring/Summer Brandon Drechsler, Brendan McGinnis, Alex Muecke, Casey Ronquillo, Bren Schader March 11, 2014 Table of Contents Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….5-6 External Analysis…………………………………………………………………………..8-19 New Event, Goals, Strategies, & Actions Programs…………………………21-44 Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard………………………………………….46-47 Risk Assessment & Contingency Plans…………………………………………..49-52 Financial Projections & Narrative……………………………………………………54-56 Building Baseline Market Awareness……………………………………………..58-66 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….68-72 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………..74-94 2 Executive Summary Lakeside Overview The Lakeside community of approximately 1,700 people in Coos County has great potential for a sporting event that could lead to an increase in tourism. With an abundance of natural resources including Tenmile Lake and the dunes, you need to gather as a community to create and organize an event that encourages people to visit time and time again. With a lack of visitors compared to other competing coastal towns in the spring and summer months, Lakeside needs to increase its brand awareness and capitalize on its existing resources to tap into the summer recreational sports industry. This is a popular industry that reaches all demographics with a trend of health living, while driving economic growth through participation. Event Overview and Action Plan We recommend Lakeside create an unique sporting event during its most popular season of the year. Through the use of marketing tools that we have suggested as well as the completion of the beach’s infrastructure, the Oregon Outdoor Experience will provide an annual summer opportunity for families and youth organizations to experience Lakeside’s offerings. This will ultimately increase the sustainable growth of Lakeside through increased revenue streams and awareness. -

Lane County Media Coverage of Wildfires and Smoke in Relation to Climate Change

LANE COUNTY MEDIA COVERAGE OF WILDFIRES AND SMOKE IN RELATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE by CHRISTA HUDDLESTON A THESIS Presented to the Department of Journalism and Communications and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2019 An Abstract of the Thesis of Christa Huddleston for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Journalism and Communications to be taken June 2019 Title: Lane County Media Coverage of Wildfires and Smoke in Relation to Climate Change Approved: Professor Mark Blaine Forest fires have been all over the news in Oregon the past two years, especially during the dry summer months which have hit record-high temperatures and record- long periods without rain. Due to nearly a century of fire exclusion, wildfires continue to get larger and wildfire season continues to get longer each year. This already devastating pattern is accelerated by climate change due to climate scientists predicting hotter and drier summers in the Pacific Northwest. Yet, existing literature shows climate change continues to be a low priority for the public. The media is one of the main avenues through which the public receives information about both forest fires and climate change. I hypothesized that most local media coverage of forest fires does not mention climate change. My thesis project analyzed local media coverage of forest fires and smoke here in Lane County using a content analysis: keyword searching for words such as ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’ in relevant articles from May 2017 through November 2018. -

Send2press® Media List 2009, Weekly U.S. Newspapers *Disclaimer: Media Outlets Subject to Change; This Is Not Our Complete Database!

Send2Press® Media Lists 2009 — Page 1 of 125 www.send2press.com/lists/ Send2Press® Media List 2009, Weekly U.S. Newspapers *Disclaimer: media outlets subject to change; this is not our complete database! AK Anchorage Press AK Arctic Sounder AK Dutch Harbor Fisherman AK Tundra Drums AK Cordova Times AK Delta Wind AK Bristol Bay Times AK Alaska Star AK Chilkat Valley News AK Homer News AK Homer Tribune AK Capital City Weekly AK Clarion Dispatch AK Nome Nugget AK Petersburg Pilot AK Seward Phoenix Log AK Skagway News AK The Island News AK Mukluk News AK Valdez Star AK Frontiersman AK The Valley Sun AK Wrangell Sentinel AL Abbeville Herald AL Sand Mountain Reporter AL DadevilleDadeville RecordRecord AL Arab Tribune AL Atmore Advance AL Corner News AL Baldwin Times AL Western Star AAL Alabama MessengerMessenger AL Birmingham Weekly AL Over the Mountain Jrnl. AL Brewton Standard AL Choctaw Advocate AL Wilcox Progressive Era AL Pickens County Herald Content and information is Copr. © 1983‐2009 by NEOTROPE® — All Rights Reserved. Send2Press® Media Lists 2009 — Page 2 of 125 AL Cherokee County Herald AL Cherokee Post AL Centreville Press AL Washington County News AL Call‐News AL Chilton County News AL Clanton Advertiser AL Clayton Record AL Shelby County Reporter AL The Beacon AL Cullman Tribune AL Daphne Bulletin AL The Sun AL Dothan Progress AL Elba Clipper AL Sun Courier AL The Southeast Sun AL Eufaula Tribune AL Greene County Independent AL Evergreen Courant AL Fairhope Courier AL The Times Record AL Tri‐City Ledger AL Florala News AL Courier Journal AL The Onlooker AL De Kalb Advertiser AL The Messenger AL North Jefferson News AL Geneva County Reaper AL Hartford News Herald AL Samson Ledger AL Choctaw Sun AL The Greensboro Watchman AL Butler Countyy News AL Greenville Advocate AL Lowndes Signal AL Clarke County Democrat AL The Islander AL The Advertiser‐Gleam AL Northwest Alabaman AL TheThe JournalJournal‐RecordRecord AL Journal Record AL Trinity News AL Hartselle Enquirer AL The Cleburne News AL The South Alabamian Content and information is Copr. -

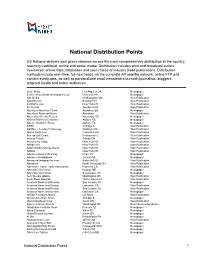

National Distribution Points

National Distribution Points US National delivers your press releases across the most comprehensive distribution in the country, reaching traditional, online and social media. Distribution includes print and broadcast outlets, newswires, online sites, databases and your choice of industry trade publications. Distribution methods include real−time, full−text feeds via the complete AP satellite network, online FTP and content syndicates, as well as personalized email newsletters to reach journalists, bloggers, targeted media and online audiences. 20 de'Mayo Los Angeles CA Newspaper 21st Century Media Newspapers LLC New York NY Newspaper 3BL Media Northampton MA Web Publication 3pointD.com Brooklyn NY Web Publication 401KWire.com New York NY Web Publication 4G Trends Westboro MA Web Publication Aberdeen American News Aberdeen SD Newspaper Aberdeen Business News Aberdeen Web Publication Abernathy Weekly Review Abernathy TX Newspaper Abilene Reflector Chronicle Abilene KS Newspaper Abilene Reporter−News Abilene TX Newspaper ABRN Chicago IL Web Publication ABSNet − Lewtan Technology Waltham MA Web Publication Absolutearts.com Columbus OH Web Publication Access Gulf Coast Pensacola FL Web Publication Access Toledo Toledo OH Web Publication Accounting Today New York NY Web Publication AdAge.com New York NY Web Publication Adam Smith's Money Game New York NY Web Publication Adotas New York NY Web Publication Advance News Publishing Pharr TX Newspaper Advance Newspapers Jenison MI Newspaper Advanced Imaging Pro.com Beltsville MD Web Publication -

DIRECTV Employment Unit ID# 11978 Castle Rock, Douglas County, Colorado 5454 Garton Rd., Castle Rock, CO 80104 EEO Public File R

DIRECTV Employment Unit ID# 11978 Castle Rock, Douglas County, Colorado 5454 Garton Rd., Castle Rock, CO 80104 EEO Public File Report Master Recruitment Source List (MRSL) Reporting Period: 9/10/2013 - 9/9/2014 Resource Type Key: P = Paper, I = Internet, I/P = Internet and Paper, O = Other Number of Interviewees Provided by RS Key Recruitment Source (RS)* Address Contact Name Phone Type in this Period AGCY-10100 Search Firm/Staffing N/A N/A N/A O 6 Agency AGNT-233542 Prosum 2321 Rosecrans Ave. Janette Dooley 626-298-2025 O 0 AGNT-233602 DIRECTV Sourcing N/A N/A N/A O 0 Partners AGNT-233622 Agency N/A N/A N/A O 0 AGNT-233682 Analytic Recruiting 144 E. 44 Street Howard Fishman 212 545-8511 O 0 AGNT-233702 Q-Lytics 1011 Brookside Road, Anie Roberts 610-530-1447 O 0 Suite 230 AGNT-233722 Modis 7887 E Belleview Steve Shawver 303-222-2445 O 1 Avenue Englewood, CO 80111 AGNT-233822 Pinpoint Resource 1960 E. Grand Avenue Paul Rottenberg 310-955-1028 O 0 Group AGNT-233882 Randstad Technologies 909 North Sepulveda Ryan Lewis 310-335-0420 O 0 U.S. Blvd AGNT-233942 Access Staffing, LLC 360 Lexington Avenue Allison Levin 646-307-8993 O 0 AGNT-233962 Robert Half Technology 1125 17th Street, Suite Delmar Dimacale 215-568-1513 O 0 870 AGNT-234022 Irvine Technology 201 Sandpointe Ave Allison Long 714-434-8808 O 0 Corporation #300 AGNT-234082 Tek Systems 3133 E. Camelback Rd. Ben Graeff 602-605-7082 O 0 AGNT-234102 iSearch Group 6230 Wilshire Blvd Michael Parker 323-933-8045 O 0 AGNT-234122 JM Search 1045 First Avenue Tom Figueroa 610-964-0200 O 0 Page 1 of 29 Number of Interviewees Provided by RS Key Recruitment Source (RS)* Address Contact Name Phone Type in this Period AGNT-234142 Fecak, Inc P.O. -

Delivering Dailies and Weeklies in Oregon, Washington and Idaho

delivering dailies and weeklies in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. OREGON • Albany Democrat-Herald, Albany 18,800 North County News, Sutherlin 1,013 Marysville Globe and Arlington Times, Woodinville Register, Woodinville 32,500 • Ashland Daily Tidings, Ashland 4,400 The New Era, Sweet Home 2,228 Marysville 11,553 • Yakima Herald Republic, Yakima 40,980 • Daily Astorian, Astoria 8,900 • The Dalles Chronicle, The Dalles 4,635 Mattawa Area News, Mattawa 1,000 Nisqually Valley News, Yelm/Ranier/Roy 4,200 • Baker City Herald, Baker City 3,550 Tigard Times, Tigard 7,400 Mercer Island Reporter, Mercer Island 5,200 IDAHO • The Record-Courier, Baker City 3,200 Headlight-Herald, Tillamook 8,300 Mill Creek Enterprise, Mill Creek 10,254 Bandon Western World, Bandon 2,600 Malheur Enterprise, Vale 1,800 Monroe Monitor Valley News, Monroe 3,985 Aberdeen Times, Aberdeen 855 Beaverton Valley Times, Beaverton 8,200 West-Lane News, Veneta 2,000 Grays Harbor County Vidette, Montesano 3,500 Power County Press, American Falls 2,010 • The Bulletin, Bend 30,586 The Columbia Press, Warrenton 968 East County Journal, Morton 3,020 Arco Advertiser, Arco 1,834 • Curry Coastal Pilot, Brookings 7,304 West Linn Tidings, West Linn 4,300 • Columbia Basin Herald, Moses Lake 8500 Morning News, Blackfoot 3,903 The Times, Brownsville 1,000 Wilsonville Spokesman, Wilsonville 3,450 • Skagit Valley Herald, Mount Vernon 19,762 Idaho Business Review, Boise 2,000 • Burns Times-Herald, Burns 31,500 Woodburn Independent, Woodburn 4,250 Mukilteo Beacon, Mukilteo 8,900 Idaho Statesman, -

Industry Letter Is Here

2020/2021 NNA OFFICERS April 13, 2021 Chair The Honorable Xavier Becerra Brett Wesner Wesner Publications Secretary of Health and Human Services Cordell, OK Hubert H Humphrey Building 200 Independence Ave SW Vice Chair John Galer Washington DC 20201 The Hillsboro Journal-New Hillsboro, IL Dear Secretary Becerra: Treasurer Jeff Mayo We write as publishers, editors and journalists at the nation’s community newspapers to urge your Cookson Hills Publishing attention to our important role in addressing small, rural, ethnic and minority communities in the new “We Sallisaw, OK Can Do This Campaign.” BOARD OF DIRECTORS Our newspapers are reaching the audiences you are looking for. We publish weekly and daily in print and Martha Diaz-Aszkenazy hourly on digital platforms to people seeking local news. Our readers are old, young, Republicans, San Fernando Valley Sun San Fernando, CA Democrats and Independents, who are highly motivated to vote, engage in civic leadership and develop their small communities. These are the audiences who can help to get shots into arms. Beth Bennett Wisconsin Newspaper Association Madison, WI To date, despite guidance from Congress in the Department’s 2021 appropriations legislation to make better use of local media, our newspapers have not been contacted for the $10 billion advertising J. Louis Mullen Blackbird LLC campaign. Newport, WA The HHS advertising should appear in April and May on our print pages, on our website and on our William Jacobs Jacobs Properties Facebook posts. Your message in our publications will be highly-focussed in a medium that is best Brookhaven, MS designed to handle powerful, complex and urgent messages. -

Column Widths for Oregon Newspapers Updated 01/01/2015

Column widths for Oregon newspapers Updated 01/01/2015 DAILIES NEWSPAPER PAGE SIZE 1 COL 2 COL 3 COL 4 COL 5 COL 6 COL Albany Democrat-Herald/Corvallis Gazette-Times 6x21.5" 1.611 3.339 5.067 6.794 8.522 10.250 Ashland, Daily Tidings 5x11.25" 1.833 3.806 5.778 7.750 9.722 Astoria, The Astorian 6x21.5" 1.611 3.389 5.167 6.944 8.722 10.500 Bend, The Bulletin 6x20.25" 1.646 3.458 5.271 7.083 8.896 10.708 Coos Bay, The World 6x21.5" 1.556 3.222 4.889 6.556 8.222 9.889 Eugene, The Register-Guard 6x21" 1.549 3.264 4.979 6.694 8.410 10.125 Grants Pass Daily Courier 6x21.5" 1.837 3.820 5.800 7.785 9.767 11.750 Klamath Falls, Herald and News 6x20.25" 1.646 3.417 5.188 6.958 8.729 10.500 LaGrande, The Observer 6x21" 1.640 3.440 5.240 7.040 8.840 10.600 Medford, Mail Tribune 6x21.5" 1.833 3.806 5.778 7.750 9.722 11.694 Ontario, Argus Observer 6x21.25" 1.528 3.222 4.917 6.611 8.306 10.000 Pendleton, East Oregonian 6x21.5" 1.625 3.400 5.175 6.950 8.725 10.500 Portland, The Oregonian 6x14" 1.625 3.400 5.175 6.950 8.725 10.500 Roseburg, News-Review 6x21.5" 1.530 3.220 4.920 6.610 8.305 10.000 Salem, Statesman Journal 6x21.5" 1.560 3.250 4.940 6.630 8.310 10.000 The Dalles Chronicle 6x21" 1.583 3.292 5.000 6.708 8.417 10.125 WEEKLIES NEWSPAPER PAGE SIZE 1 COL 2 COL 3 COL 4 COL 5 COL 6 COL Baker City Herald 6x21" 1.640 3.440 5.240 7.040 8.840 10.600 Baker City, Record-Courier 5x21" 1.900 3.925 5.950 7.975 10.000 Bandon Western World 6x21.5" 1.556 3.222 4.889 6.556 8.222 9.889 Beaverton Valley Times 6x21" 1.700 3.500 5.375 7.200 9.000 10.875 Brookings, -

Oregon State Bar Board of Governors Minutes

Oregon State Bar Special Open Meeting of the Board of Governors May 24, 2012 Minutes The meeting was called to order by President Mitzi Naucler at 5:00 p.m. on May 24, 2012. The meeting adjourned at 5:30 p.m. Members present from the Board of Governors were Jenifer Billman, Hunter Emerick, Ann Fisher, Michael Haglund, Ethan Knight, Theresa Kohlhoff, Tom Kranovich, Steve Larson, Maureen O’Connor, Travis Prestwich and Richard Spier. Staff present were Sylvia Stevens, Helen Hierschbiel, Rod Wegener, Kay Pulju, Susan Grabe, Judith Baker and Camille Greene. Board members not present: Barbara DiIaconi, Patrick Ehlers, Michelle Garcia, Matthew Kehoe, Audrey Matsumonji and David Wade. 1. Replacement Appointment to the Client Security Fund In the absence of Appointments Committee Chair, Barbara DiIaconi, Steve Larson presented the committee’s recommendation of Ronald Atwood as replacement appointment to the Client Security Fund. Mr. Atwood’s term will expire 12/30/2014. Motion: The board voted unanimously to approve the committee motion for the appointment as recommended. [Exhibit A] 2. Centralized Legal Notice System Ms. Baker provided the board with a draft business plan for the Centralized Legal Notice System. A discussion followed. The board agreed that more information would be needed before the BOG can decide whether to proceed. [Exhibit B] BOG Open Minutes – Special Meeting March 30, 2012 OREGON STATE BAR Board of Governors Agenda Meeting Date: May 24, 2012 Memo Date: May 24, 2012 From: Barbara DiIaconi, Appointments Committee Chair Re: Volunteer Appointments to Various Boards, Committees, and Councils Action Recommended Approve the following Appointments Committee recommendations. -

Reginal Add Placementsx

Regional Ad Placements This is a list of all the regional ad placements throughout the state of Oregon for the I Work We Succeed Campaign, promoting community jobs for people with developmental and intellectual disabilities. This list is separated by county in alphabetical order and describes the types of ad placed in each county. Statewide: • Disability Scoop: Online ad • Facebook Ad Campaign • Oregon Business Magazine: print and online ad • Catholic Sentinel/El Centinela • Radio: Statewide Public Educational Awareness Program will air Monday, June 29 - Sunday, September 20, 2015 (178 commercial radio stations possible) Regional Ad Placements Below is a sample of what the billboards will look like and which region they will be displayed Central Oregon Roseburg/Southern Oregon Regional Ad Placements Eugene/Willamette Valley Portland Area Eastern Oregon Regional Ad Placements Baker County: • Newspapers: Baker City Herald (print and online); Baker City Record Courier • Billboard: Baker City Highway 86 • Radio: KCMB-FM; KMKR-AM; KKBC-FM Benton County: • Newspaper: Corvallis Gazette Times (online and print) • Billboard: Corvallis Highway 34 (2 locations) • Transit: 5 Exterior Street Side Ads; 3 Exterior Curb Side Ads; 12 insert cards • Radio: KEJO-AM; KLOO-AM; KLOO-FM Clackamas County: • Newspapers: Canby Herald, Estacada News, Lake Oswego Review; Molalla Pioneer; Sandy Post; West Linn Tidings, Clackamas Review, Wilsonville Spokesman • Transit: Portland Metro Area: 30 Exterior Street Side Ads, 30 Exterior Curb Side Ads; 20 Outside Rear/Tail Ads; and 50 Interior Ads. Regional Ad Placements Clatsop County: Newspapers: Daily Astorian (print and online) Columbia County: Newspaper: Scappoose So City Spotlight; St. Helens Chronicle Billboard: US 30, Scappoose; Highway 30 St.