Chapter7.Pdf (PDF, 722.3Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

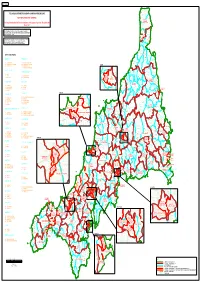

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Gilly Vean Farm South Cornwall

Gilly Vean Farm South Cornwall Gilly Vean Farm GWENNAP, SOUTH CORNWALL, TR16 6BN Farmhouse set centrally within extensive grounds with equestrian facilities, countryside views and potential for holiday lets. Available for the first time in 26 years Secluded position within private grounds Close to both Falmouth and Truro Charming main residence Rolling countryside views Planning consent for holiday lettings Sand school, stables, tack and feed rooms Approx. 26.55 acres Falmouth – 6.5 Truro – 8 St Agnes – 10 Helford – 10.5 Cornwall Airport (Newquay) – 26.5 (all distances are approximate and in miles) Savills Truro 73 Lemon Street Truro, TR1 2PN Tel: 01872 243200 [email protected] savills.co.uk THE PROPERTY Originally built in the 1850s, Gilly Vean Farm is located at the end of a long private driveway set within the centre of its own grounds, therefore affording great privacy. The original farmhouse has been extended to join the adjacent traditional buildings and now provides unique and highly versatile 4-bedroomed accommodation with two principal reception rooms, snug, a home office and the potential for an integral annexe. There is extensive stabling and planning consent for conversion. Entering the property through the charming and picturesque courtyard, a glazed entrance lobby leads through to the kitchen with an outlook over the front courtyard, arranged around a central island and includes an electric range within the former fireplace, and through to the main body of the farmhouse. The study and snug lead on to a beautiful sitting room defined by painted beams and an open fireplace with the conservatory leading out to the attractive and mature front gardens. -

Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason BALDHU St. Michael & All Angels BALDHU Cornwall Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St. Pratt BLISLAND Cornwall Truro 1894-1895 Reseating/Repairs BOCONNOC Parish Church BOCONNOC Cornwall Truro 1934-1936 Repairs BOSCASTLE St. James MINSTER Cornwall Truro 1899 New Church BRADDOCK St. Mary BRADDOCK Cornwall Truro 1926-1927 Repairs BREA Mission Church CAMBORNE, All Saints, Tuckingmill Cornwall Truro 1888 New Church BROADWOOD-WIDGER Mission Church,Ivyhouse BROADWOOD-WIDGER Devon Truro 1897 New Church BUCKSHEAD Mission Church TRURO, St. Clement Cornwall Truro 1926 Repairs BUDOCK RURAL Mission Church, Glasney BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1908 New Church BUDOCK RURAL St. Budoc BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1954-1955 Repairs CALLINGTON St. Mary the Virgin CALLINGTON Cornwall Truro 1879-1882 Enlargement CAMBORNE St. Meriadoc CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1878-1879 Enlargement CAMBORNE Mission Church CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1883-1885 New Church CAMELFORD St. Thomas of Canterbury LANTEGLOS BY CAMELFORD Cornwall Truro 1931-1938 New Church CARBIS BAY St. Anta & All Saints CARBIS BAY Cornwall Truro 1965-1969 Enlargement CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1896 Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1907-1908 Reseating/Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1943 Repairs CARHARRACK Mission Church GWENNAP Cornwall Truro 1882 New Church CARNMENELLIS Holy Trinity CARNMENELLIS Cornwall Truro 1921 Repairs CHACEWATER St. Paul CHACEWATER Cornwall Truro 1891-1893 Rebuild COLAN St. Colan COLAN Cornwall Truro 1884-1885 Reseating/Repairs CONSTANTINE St. Constantine CONSTANTINE Cornwall Truro 1876-1879 Repairs CORNELLY St. Cornelius CORNELLY Cornwall Truro 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs CRANTOCK RURAL St. -

Truro/St Agnes Area)

Information Classification: PUBLIC Cornwall Community Governance Review Public Engagement Meeting (Truro/St Agnes Area) Parishes being focused on at this public engagement meeting: Truro, Kenwyn, St Clement, Chacewater – in Truro & Roseland Community Network Area; St Agnes – in St Agnes & Perranporth Community Network Area Note: If you would like to speak during this meeting, please make sure you register your interest with the Cornwall Council officers stationed at the entrance door. Date: Tuesday 15 October 2019 Time: 7.00pm-9.30pm (6.30: Tea & Coffee; opportunity for informal networking) Location: Council Chamber, New County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY Interactive map link: https://goo.gl/maps/Ua8vr2Czy9brKRtP8 Parking: On site Chair/Vice- Malcolm Brown CC (Chair of the Electoral Review Panel) Chair Dick Cole CC (Vice-Chair of the Electoral Review Panel Agenda: 1. Welcome & Introduction by the Chair 2. Parishes being focused on in this section of the meeting: Truro, Kenwyn and St Clement (i) Those listed below to have opportunity to give brief verbal summary of their submissions (“URN” refers to the unique reference number in the published list of submissions): A Representative of Truro City Council (URN 718) A Representative of Kenwyn Parish Council (URN 707) A Representative of St Clement Parish Council (URN 712) 1 Information Classification: PUBLIC (ii) Questions about these Submissions from Members of the Panel and Substitute Members (iii) Statements about these Submissions by Other Parish and Town Councillors and Members of the Public Present Note: The Chair has indicated that if St Erme, Probus and St Michael Penkivel Parish Councils wish to make statements about the St Clement submission, they will be heard first during this item. -

Gwennap War Memorial

GWENNAP WAR MEMORIAL Compiled by Barbara Wilkinson The War Memorial at Gwennap was unveiled on Saturday 17 July 1920 to commemorate the dead of the First World War, and the ceremony was reported in the West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser on Thursday 22 July 1920. Other local newspapers also carried the story. GWENAPP’S CROSS UNVEILED BY THE LORD LIEUTENANT The Lord‐Lieutenant of Cornwall (Mr. J.C. Williams), on Saturday, unveiled the memorial erected by the parishioners of Gwennap in memory of 16 men from the parish who made the supreme sacrifice in the war. The memorial consists of a beautiful cross of Cornish granite, standing eleven feet high, which has been placed on a piece of elevated ground near the boundary wall of the parish churchyard. The inscription reads:‐ “To the honour of those who at the call of King and Country gave up all that was dear to them that others might live in freedom, 1914‐1918” Underneath are the following names: Harry Powys Rogers, James Phillips, Thomas Collins, James Gleed, Arthur Prowse, William Trenery, William Hitchins, Richard Ford, Thomas Carbis, William Tregoning, William Collins, John Hooker, Gilbert Pelmear, James Annear, Philip Russell, George Pelmear. The arrangements for the memorial, costing about £70, were made by a committee, consisting of the vicar, Rev. J.L. Parker (chairman) Messrs. Towan Hancock, G.E. Prowse and R.T. Harris. The clergy and ministers taking part in Saturday’s unveiling ceremony were the Revs. J.L. Parker (vicar), W.H.C. Nalton (vicar of Lannarth), H. Hopkinson (superintendant minister of Gwennap Wesleyan Circuit), and W. -

Truro and Kenwyn Neighbourhood Plan

Truro and Kenwyn Neighbourhood Plan Post Examination Draft 2015 - 2030 0 CONTENTS CONTENTS ___________________________________________________________ 1 Foreword by our Chair _________________________________________________ 2 Introduction _________________________________________________________ 3 Vision and objectives __________________________________________________ 6 Environment _________________________________________________________ 7 Economy and jobs____________________________________________________ 15 Education __________________________________________________________ 23 Housing ____________________________________________________________ 26 Leisure and Culture ___________________________________________________ 31 Transport __________________________________________________________ 38 Historic Environment _________________________________________________ 42 Summary of policies __________________________________________________ 47 1 Foreword by our Chair Thank you for taking part in shaping the future of Truro and Kenwyn parishes. The following pages lay out a plan for Truro and Kenwyn that has been created by local people for local people. The plan aims to meet the needs, hopes and aspirations of local people. I am very appreciative of the hard work of many people who have given their time freely to develop The Truro and Kenwyn Neighborhood Plan. From the Councillors of Truro City Council and Kenwyn Parish Council who came together in the Steering Group, and who have since worked with a wide range of local people and organisations, -

LCAA7067 £850000 Dalleth an Vounder, Kenwyn Church

Ref: LCAA7067 £850,000 Dalleth An Vounder, Kenwyn Church Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3DR FREEHOLD Located in one of Truro’s foremost residential locations, in an idyllic traffic free private road enjoying peace and tranquillity yet walking distance from Truro city centre. One of an incredible select development of just four brand new contemporary homes with a fantastic individual design, wonderful proportions and a superb level of specification. With approximately 2,400sq.ft of 4/5 bedroomed, 3 bath/shower roomed accommodation including an exceptional part-galleried living space, integral double garage, parking for numerous vehicles and large south east facing gardens and a fantastic sylvan outlook. 2 Ref: LCAA7067 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: entrance hall, open-plan kitchen/dining/family room (23’4” x 17’6”), sitting room with woodburning stove, study, cloakroom/wc, plantroom, utility room/rear hall, integral double garage. First Floor: Part-galleried landing, master bedroom with en-suite shower room and Juliet balcony, guest bedroom with en-suite shower room and Juliet balcony, 2 further double bedrooms, family bathroom. Outside: tarmacadam driveway with parking for 3/4 cars, deep private verge area from below lane, large full width paved sun terrace, part walled garden, gently sloping recently seeded lawned garden with mature tree and hedge borders. DESCRIPTION • Kenwyn Church Road has long been regarded as one of Truro’s foremost residential locations, located close to Kenwyn Church in a beautiful leafy private road which is an oasis of peace, tranquillity and seclusion yet still within easy walking distance from Truro city centre. • Dalleth An Vounder (meaning ‘Beginning of Lane’ in Cornish) is part of an incredible select development of just four brand new contemporary homes, each of individual design and wonderful proportions and displaying a superb level of specification. -

Ernie, Probus, Newlyn, Saint Allen, Truro, the Borough of Truro, Saint

6617 Ernie, Probus, Newlyn, Saint Allen, Truro, the near the town of Bridgwater, in the same county, borough of Truro, Saint Clement Trufo, Saint and passing from, through, or into the several Mary Truro, Kenwyn, Kea, Tregavethan, Saint parishes, townships, townlands, and extra-parochial Feock, Gweunap, Perranarworthal, Gluvias other- and other places of Saint John the Baptist Glas^ wise Saint Gluvias, Mylor, Stithians, Mabe, Pen- tonbury, Street, Walton, Ashcott, King's Sedge'- ryn, the borough of Penryn, Budock, Falmouth, moor, Butleigh, Greinton otherwise Grenton, the borough of Falmouth, or some of them in the Pedwell, Shapwick, Moorlinch, Sutton Mallett, county of Cornwall, Stawell, Catcott, Edington Chilton Super Polden, Fourth, a railway diverging from and out of the Cossington, Woolavington, Puriton, Bawdrip, intended railway last above described at, in, or Bradney, Chedzoy, Weston Zoyland, North Pe- near the borough of Truro, in the county of Corn- therton, Chilton Trinity, Wembdon, Bridgwater, wall, aud terminating at, in, or near the borough of Horsey, Dnnwear, Heygrove, East Bower, the Penzance,, in the parish of Madron, in the county borough of Bridgwater, or some of them, in the of Cornwall, and passing from, through, or iuto the county of Somerset. several parishes, townships, townlands, and extra- And notice is hereby further given, than plans parochial and other places of Saint Mary Truro, and sections describing the lines, levels, and situa- Saint Clement Truro, Kenwyn, Gwennap, Tregave- tion of the said intended railways -

The Micro-Geography of Nineteenth Century Cornish Mining?

MINING THE DATA: WHAT CAN A QUANTITATIVE APPROACH TELL US ABOUT THE MICRO-GEOGRAPHY OF NINETEENTH CENTURY CORNISH MINING? Bernard Deacon (in Philip Payton (ed.), Cornish Studies Eighteen, University of Exeter Press, 2010, pp.15-32) For many people the relics of Cornwall’s mining heritage – the abandoned engine house, the capped shaft, the re-vegetated burrow – are symbols of Cornwall itself. They remind us of an industry that dominated eighteenth and nineteenth century Cornwall and that still clings on stubbornly to the margins of a modern suburbanised Cornwall. The remains of this once thriving industry became the raw material for the successful World Heritage Site bid of 2006. Although the prime purpose of the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site team is to promote the mining landscapes of Cornwall and west Devon and the Cornish mining ‘brand’, the WHS website also recognises the importance of the industrial and cultural landscapes created by Cornish mining in its modern historical phase from 1700 to 1914.1 Ten discrete areas are inscribed as world heritage sites, stretching from the St Just mining district in the far west and spilling over the border into the Tamar Valley and Tavistock in the far east. However, despite the use of innovative geographic information system mapping techniques, visitors to the WHS website will struggle to gain a sense of the relative importance of these mining districts in the history of the industry. Despite a rich bibliography associated with the history of Cornish mining the historical geography of the industry is outlined only indirectly.2 The favoured historiographical approach has been to adopt a qualitative narrative of the relentless cycle of boom and bust in nineteenth century Cornwall. -

September 2019

OUR NEWS SEPTEMBER 2019 SIGN UP TO OUR MAILINGS HERE TAKING THE NEXT STEP: VOCATIONS DAY & FOND FAREWELL TO +CHRIS Bishop Chris’ leaving service will be an integral part of this year’s Diocese of Truro Vocations Day in the cathedral on Saturday, September 14 - and it couldn’t be more fitting. Before his ordination, Bishop discerning how you can ARCHDEACON WILL BE Chris spent many years as answer that call. a Reader, and even longer INSTALLED THIS SUNDAY as a disciple committed to Both Bishop Philip and bringing Christian values Bishop Chris will be there for The Venerable Paul Bryer will be installed into the workplace and other the day, and attendees will as the new Archdeacon of Cornwall on areas of life – and the next have an opportunity to hear Sunday, September 1 during a service at step on his pilgrimage is to from each of them. Truro Cathedral. head up the Ministry Division All are invited to attend the service, for the Church of England. In this The day will be punctuated by the which starts at 4pm, and welcome new role he will lead a team looking opportunity to talk in small groups Paul to the diocese. Refreshments will to encourage and increase the scale with facilitators. This will help those be served in the cathedral after the and diversity of those called to both who come along to explore the call Evensong and installation. lay and ordained ministries within the they might be experiencing and what church. the next steps might be for them. + READ MORE Vocations Day open to all Tea & cake Vocations Day is an opportunity for After lunch, people will come together DIOCESAN SYNOD TO BE anybody to explore their calling – at 1.30pm for worship and the service whatever that might be. -

840 Tauao. CORNWAJ

840 Tauao. CORNWAJ .. L. [KELL'Y'B Land Steward, Alex. W. Webster & V\7. Proudfoot esqrs Registrar of County Court, Admiralty, Bankruptcy & Agent & Surveyor, Manor of Kennington, C. Barker esq Stannaries, Gilbert H. Chilcott., St. Mary's street Mineral Inspector, T. Forster Browlt esq Surveyor of West Powder Highway Board, John Retal Sheriff of Cornwall, Richard Carlyon Coode esq. Polapit lack, Calle;;tock S.O Tamar, Launceston COUNTY OFFICIALS. Rider & Master Forester of the Forest of Dartmoor, Earl of Ducie P.C., F.R.S Ccrcner for the Central Division of the County, E. Bailiff of the Forest. of Dartmoor, A. E. Barrington esq . La.urence Oarlyon, 5 Boscawen street; deputy, Robert Ste\\ard of the Manor Courts, Sir Maurice Holzmann Horace William Dybell, 9 Pydar street G.C.V.O., C.B., I.S.O County Financial Clerk, W. J. Mock, 68 Lemon street Deputy Steward, W. Peacock esq Secretary to County Council Education Committee, R. F. Pascoe B.A. 63 Lemon street STANXARIES OOURT FOR CORl\'WALL & DEVO~. Inspector of Weights & Measures, Chief Constable Frank This court, formerly held at Truro quarterly, is now Pearce, Town hall transferred to the County Court jurisdiction DIOCESE OF T·RURO. 'I'RURO UKION. r89r Bishop, Right Rev. John Gott D.D. Trenython, Board day, alternate wednesdays at rr a.m. at the Work- Par Station & Lis Escop, Kenwyn, Truro • house, St. Clement's. r8gr Dean, The Lord Bishop The Union comprises the following p.ui:!hes, viz. :-St. rgo5 Bishop Suffragan of St. Germans, Right Rev. John Agnes, St. Anthony in Roseland, St. -

Cornwall's Ward Boundaries

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND MORWENSTOW CP ELECTORAL REVIEW OF CORNWALL STRATTON, KILKHAMPTON Final recommendations for division boundaries in the county of Cornwall December 2018 & MORWENSTOW Sheet 1 of 1 KILKHAMPTON CP Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information F applied as part of this review. LAUNCELLS BUDE-STRATTON CP D CP BUDE This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey E on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. MA The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2018. RHA MCH URC H CP POUNDSTOCK CP KEY TO PARISH WARDS POUNDSTOCK WHITSTONE CP BODMIN CP PENZANCE CP P WEEK ST NORTH C MARY CP ST W TAMERTON CP O GENNYS CP T S A ST LAWRENCE AV HEAMOOR & GULVAL B O C B ST MARY'S & ST LEONARD AW NEWLYN & MOUSEHOLE A BODMIN J C ST PETROC'S AX PENZANCE EAST AY PENZANCE PROMENADE BUDE-STRATTON CP WARBSTOW CP (DET) BOYTON CP PERRANZABULOE CP ST JULIOT CP OTTERHAM F CP NORTH D BUDE O WARBSTOW CP B R PETHERWIN CP C T E HELE AZ GOONHAVERN T R R S A E N & BODMIN CP B M T C F STRATTON BA PERRANPORTH MI 'S R U A D Y LESNEWTH P D BODMIN ST E R I V N BO AR ST A Y CP E LAUNCESTON M PETROC'S L A WERRINGTON ONAR G N NORTH & NORTH E A D CP L C TRENEGLOS PETHERWIN CAMBORNE CP REDRUTH CP P M I CP TRESMEER N CAMELFORD & A S CP TINTAGEL CP T BOSCASTLE E G ROSKEAR