An Idiomatic Plucked String Player

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lute Tuning and Temperament in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

LUTE TUNING AND TEMPERAMENT IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES BY ADAM WEAD Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University August, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. Nigel North, Research Director & Chair Stanley Ritchie Ayana Smith Elisabeth Wright ii Contents Acknowledgments . v Introduction . 1 1 Tuning and Temperament 5 1.1 The Greeks’ Debate . 7 1.2 Temperament . 14 1.2.1 Regular Meantone and Irregular Temperaments . 16 1.2.2 Equal Division . 19 1.2.3 Equal Temperament . 25 1.3 Describing Temperaments . 29 2 Lute Fretting Systems 32 2.1 Pythagorean Tunings for Lute . 33 2.2 Gerle’s Fretting Instructions . 37 2.3 John Dowland’s Fretting Instructions . 46 2.4 Ganassi’s Regola Rubertina .......................... 53 2.4.1 Ganassi’s Non-Pythagorean Frets . 55 2.5 Spanish Vihuela Sources . 61 iii 2.6 Sources of Equal Fretting . 67 2.7 Summary . 71 3 Modern Lute Fretting 74 3.1 The Lute in Ensembles . 76 3.2 The Theorbo . 83 3.2.1 Solutions Utilizing Re-entrant Tuning . 86 3.2.2 Tastini . 89 3.2.3 Other Solutions . 95 3.3 Meantone Fretting in Tablature Sources . 98 4 Summary of Solutions 105 4.1 Frets with Fixed Semitones . 106 4.2 Enharmonic Fretting . 110 4.3 Playing with Ensembles . 113 4.4 Conclusion . 118 A Complete Fretting Diagrams 121 B Fret Placement Guide 124 C Calculations 127 C.1 Hans Gerle . -

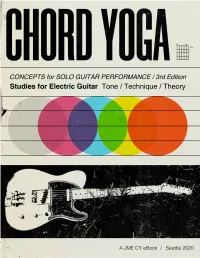

From 'Concepts for Solo Guitar Performance

Part I Studies for electric guitar Tone - Technique - Theory Pitch, texture and dynamics 1. Sound consistency ……………………………………………………………………………………….…....1 2. Synchronizing left and right hand …………………...….………………………………........2 Posture Fretting hand permutations / tone production Rhythmic and dynamic balance Legato playing ‘Two-line’ scale exercises Chordal playing: - picking patterns / permutations / dynamics - posture / preparing notes - block chords and dynamic control - adding chord shapes - ‘blurring the lines’ - combining single-notes and chordal playing Studies for electric guitar ‘Stella Watches The Stars’ …………………………………………………….………………………......7 ‘Nioma’ - blues riffs in DADGAD tuning ‘Chet’s Dream’ ‘Slow Dancing’ - a John Mayer-inspired guitar stroll ‘Akane’ ‘How to Pass A Blue Monk’ - jazz blues study Applied Music Theory 1. Jazz blues analysis …………………………………………………………...…....……….......…............... 16 2. ‘Tele moves’ - licks and riffs, triad inversions 3. ‘Neo soul flares’ - lick concepts by Chalmers ‘Spanky’ Alford 4. Arranging grooves for solo guitar 5. Arranging for solo guitar: basics ……………………………..………………………..................... 23 - melodic phrases and harmonic progressions - chord-melody: ‘gospel chords’ and (re)harmonization ideas - solo guitar arrangement: ‘Amazing Grace’ 6. ‘Shenandoah’ - Bill Frisell (solo): transcription & analysis ….......................... 27 © JME / CY, Inc. 2020 1 Tone & technique Pitch, texture and dynamics 1. Sound consistency Ex. 1 A7 A 7à13 E7 A7 b 3 œ 3 # œ œn œ œ œ œ j ## 4 œ œ œ œn œ œ œ œ œ œ# œ. œ# 3 3 œ . Ó V 4 œn 3 œb 3 œn œ# j nœ 3 œ hold bend œ œ. 3 3 3 œ 3 3 3 3 full H H j 5 0 12 j 8 5 7 12 5 6 5 11 13 13 13 13 (11) 9 5 6 5 4 11 9 5 0 10 11 0 0 Ó 0 The term // tone [tōn] // can be defined as your perception of the interplay of pitch, texture and dynamics. -

Exploration of Unorthodox Tunings and Muscle Memory Practice for the Electric Guitar

EXPLORATION OF UNORTHODOX TUNINGS AND MUSCLE MEMORY PRACTICE FOR THE ELECTRIC GUITAR LEE ANTHONY JONES SCHOOL OF ARTS AND MEDIA SALFORD MUSIC RESEARCH CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF SALFORD SALFORD, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) September 2018 Table of Contents List of Tables and Illustrations iii Glossary of Terms iv Acknowledgements vii Abstract viii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review 4 Chapter 3: Methodology 47 Chapter 4: Commentary 59 Chapter 5: Conclusion and Suggestion for Future Research 91 Bibliography 95 Discography 115 Appendix I: 118 CD Track Lists 119 CDs of Recordings 120 Appendix II: 121 Directory of Muscle Memory Patterns / Shapes 122 Appendix III: 133 12 Short Solo Studies (1-7) 134 12 Short Solo Studies (8-12) 137 Etude for Two Guitars Score 140 Not That That Helps Score 142 Valentine Fog Clears Score 144 Chinese Whispers Score 146 i Chromatic Attack Score 148 Babylon Bells Score 150 Surf-Dale Score 151 Kotofuzz Score 153 Augmented Realism Score 155 Volcanic Waltz Score 157 All’s Well, End’s Well Score 159 Night Train to Mumbai Score 161 Twelve Constellations Score 163 ii List of Tables and Illustrations Figure 1: Table of Alternate Tunings 47 Figure 2: Extract from Solo Study 2 49 Figure 3: Comparison of Standard/C#ADGAD Tuning 53 Figure 4: Comparison of Standard/Chromatic Tuning 54 Figure 5: Amaj7#5 chord voicing derived from Chromatic Tuning 54 Figure 6: Photo of Guitar Ibanez JSM10 63 Figure 7: Photo of Fender Blues Deluxe Amplifier and -

What Makes Music Sound Good?

MUSIC 105 Prof. Dmitri Tymoczko Handout 1 (2010) What Makes Music Sound Good? Intuitively, some combinations of notes sound better than others. What’s the difference between good-sounding and bad-sounding combinations? While we cannot answer this question absolutely (since there’s no accounting for taste), we can identify five different properties that are common to a very wide range of styles, from early Medieval music to contemporary popular music. They are: 1. Conjunct melodic motion. Melodies tend to move by short distances from note to note. Large leaps sound inherently unmelodic. 2. Harmonic consistency. The chords in a passage of music, whatever they may be, tend to be structurally similar to one another. 3. Acoustic consonance. Some chords sound intrinsically good or pleasing. These are said to be consonant. 4. Scales. Over small spans of musical time (say 30 seconds or so), most musical styles tend to use just a few types of notes, between 5 to 8. 5. Centricity. Over moderate spans of musical time, one tonic note is heard as being more prominent than the others, appearing more frequently and serving as a goal of musical motion. These five properties make an enormous difference to our immediate experience; in fact, you can take completely random notes and make them sound reasonably musical, simply by forcing them to conform to these requirements. In this class, we’ll think about two different sorts of questions. First, how in principle can these various properties be combined? For example, if you want to combine the first two properties (short melodies and chords that sound similar) what sorts of chords should you use? And second, how have previous composers these different features? We will see that different styles (including Renaissance music, classical music, Romantic music, jazz and rock) all involve slightly different ways of deploying the same basic properties. -

Picked Acoustic

Table of Contents 1. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Welcome to PICKED ACOUSTIC ................................................................................. 2 2.1. About SESSION GUITARIST – PICKED ACOUSTIC .......................................... 2 3. Using PICKED ACOUSTIC .......................................................................................... 4 3.1. Playing Melodies .............................................................................................. 4 3.2. Combining Melodies and Patterns ..................................................................... 5 3.3. Pattern Selection and Playback ......................................................................... 6 3.4. Playing Manual or Automatic Chords ................................................................. 7 3.4.1. The Voicing Generator and Auto Chords .................................................. 8 3.5. Playing Endings and Slides ............................................................................... 9 3.6. Controlling the Dynamics of the Performance ................................................... 10 3.7. Loading / Saving Sound Presets ...................................................................... 10 3.8. Locking Parameters When Loading Snapshots or Songs ................................... 11 3.9. Resetting the Round Robin Counter .................................................................. 11 3.10. Defining -

United States Patent (19)

United States Patent (19) 11 4,092,895 Zabel 45 June 6, 1978 54 ELECTRONICPIPE ORGAN CONTROL input signals therefrom, and respectively convert same SYSTEM into a time based serial digital signal wherein each note 76) Inventor: William P. Zabel, 81 18 N. Sakaden of the keyboard occupies a particular interval of time in Pkwy., Fort Wayne, Ind. 46825 the digital signal. The serialized signal of an input regis ter propagates through a digital delay line at a predeter 21 Appl. No.: 747,536 mined clock frequency. Selected ones of the delayed 22 Filed: Dec. 6, 1976 digital signals provided thereby are tapped to derive octave and mutation pitch signals. Accessory circuits (51) Int. C.’................................................ G10B 3/10 receive the serialized digital signals and using combina 52 U.S. C. .......................... as 84/345; 84/337; tional and sequential digital techniques modify the digi 84/341 tal signals to provide reiteration, pizzicato, sostenuto (58 Field of Search ..................... 84/1.01, 1.03, 1.17, and the like effects. The tapped signals and modified 84/337-339, 341, 343-345 signals are selectively combined with logical gates (56) References Cited under the control of the organ "stops” to provide the U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS unification and accessory functions. The combined digi tal signals are routed to control specified organ pipes 3,160,051 12/1964 Guenther ............................... 84/337 through a plurality of rank drivers which receive the 3,501,990 3/1970 Jappe et al. ............................ 84/337 serialized signals and produce a plurality of periodically Primary Examiner-Edith S. Jackmon updated parallel signals therefrom to effect sound re Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Ronald D. -

List of Guitar Tunings

List of guitar tunings This list of guitar tunings supplements the article guitar tunings. In particular, this list contains more examples of open and regular tunings, which are discussed in the article on guitar tunings. In addition, this list also notes dropped tunings. Contents 1 Open 1.1 Major 1.1.1 Open A 1.1.2 Open B A FuniChar D-616 guitar 1.1.3 Open C with a Drop D tuning. It has an 1.1.4 Open D unusual additional fretboard 1.1.5 Open E that extends onto the 1.1.6 Open F headstock. Most guitarists 1.1.7 Open G obtain a Drop D tuning by 1.2 Minor: Cross-note 1.3 Modal detuning the low E string a 1.4 Extended chord tone down. 2 Regular Tunings 2.1 Major seconds 2.2 Minor thirds 2.3 Major thirds 2.4 All Fourths 2.5 Augmented fourths 2.6 All fifths: "Mandoguitar" 2.6.1 New standard tuning 2.7 Ostrich tuning 3 Dropped 3.1 Examples 4 Shifted 4.1 Lowered 4.2 Raised 4.3 Double-dropped 5 Miscellaneous 5.1 Dad-Gad 5.2 Dad-Dad 5.3 Cello/Standard guitar 5.4 "Karnivool" tuning 5.5 Mi-composé 5.6 "Iris" Tuning 5.7 E-A-C#-F#-A-C# ("Sleeping Ute") 5.8 FGC3 5.9 Microtonal tuning 5.10 Guitar tunings inspired by other Instruments 6 Extended range and other guitar tunings 6.1 Five-string 6.2 Seven-string 6.2.1 Lower 6.2.2 Higher 6.2.3 Dropped 6.3 Eight-string 6.3.1 Lower 6.3.2 Higher 6.3.3 Dropped 6.4 Nine-string 6.4.1 Lower 6.4.2 Dropped 6.5 Ten-String 6.6 Steel Guitar 6.7 Renaissance lute 7 References 7.1 Sources 8 Further reading 9 External links Open Main article: Open tuning Major Major open-tunings give a major chord with the open strings. -

ATG Guitar Feature Packs V3.32

Auto-Tune® for Guitar Software Pack User Manual v3.32 Andy Hildebrand October 2015 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1 Guitars: Are They Mystery, or Are They Science? ..................... 8 Chapter 2 The Development of ATG and the People Who Took Part ......... 16 Chapter 3 Hardware Implementation ..................................................... 20 Chapter 4 String Tune and Solid-Tunetm .................................................. 22 Chapter 5 Fret Control ............................................................................ 25 Chapter 6 MIDI Control ........................................................................... 31 Chapter 7 Encoder Control ...................................................................... 39 Chapter 8 Custom Alt Tuning and Custom Doubling ................................ 41 Chapter 9 Brief Instructions and User Tip Summary ................................. 43 Appendix: Appendix 1 Summary of release v3.00 ………………….……………………………... 47 Appendix 2 Summary of release v3.10 ………………….……………………………... 49 Appendix 3 Summary of release v3.32 ………………….……………………………... 50 2 Introduction The electric guitar is a musical instrument. In the hands of a skilled guitarist, it is subtle and responsive. There are many playing techniques; strumming, plucking, palm muting, harmonics, plucked harmonics, hammer-on, finger mutes, string mutes, etc. The electric guitar is as complex, or more complex, than a violin or a saxophone. -

Instrumental Transformations in Heinrich Biber’S Mystery Sonatas *

Instrumental Transformations in Heinrich Biber’s Mystery Sonatas * Jonathan De Souza NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.4/mto.20.26.4.desouza.php KEYWORDS: violin scordatura, Heinrich Biber, Mystery Sonatas, performance and analysis, transformational theory, altered auditory feedback, musical instruments ABSTRACT: Each of Heinrich Biber’s Mystery Sonatas features a distinct violin tuning. How do these scordatura relate to standard tuning? How might they affect the sonatas’ musical organization and players’ experience? Transformational voice-leading theory helps to reveal overlapping categories here. Quintal scordatura include adjacent-string fifths, creating zones where notated and sounding intervals match. Chordal scordatura, in which the strings realize a triad, involve more displacement. Psychological research on altered pitch feedback suggests that scordatura are most unseling for players when they preserve aspects of standard tuning. Analyzing scordatura, then, shows how instruments function as spaces for musical action. DOI: 10.30535/mto.26.4.1 Received November 2019 Volume 26, Number 4, December 2020 Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory [0.1] In “Some Ideas about Voice-Leading between PCSets,” David Lewin writes: “Suppose you want to retune your violin, so that all its open strings sound notes of the F major harmony. Maximally close voice leading indicates ways of doing so with (in some sense) as lile overall strain as possible” (1998, 38). He demonstrates two possibilities (see Example 1a and b). With both, the E string rises one semitone, the A string remains unchanged, and the D string drops to middle C.