The Pictou Cattle Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

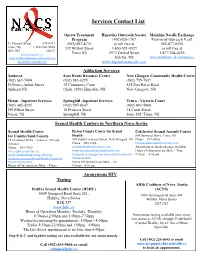

Services Contact List

Services Contact List Opiate Treatment Hepatitis Outreach Society Mainline Needle Exchange Program (902)420-1767 Provincial Outreach # call 33 Pleasant Street, 895-0931 (902) 893-4776 or toll free at 902-877-0555 Truro, NS 1 866-940-AIDS 332 Willow Street 1-800-521-0527 or toll free at B2N 3R5 (2437) [email protected] Truro NS 2973 Oxford Street 1-877-904-4555 www.northernaidsconnectionsociety.ca Halifax, NS www.mainlineneedleexchange.ca facebook.com/nacs.ns www.hepatitisoutreach.com Addiction Services Amherst- East Hants Resource Center New Glasgow Community Health Center (902) 667-7094 (902) 883-0295 (902) 755-7017 30 Prince Arthur Street 15 Commerce Court 835 East River Road Amherst,NS (Suite #250) Elmsdale, NS New Glasgow, NS Pictou - Inpatient Services Springhill -Inpatient Services Truro - Victoria Court (902) 485-4335 (902) 597-8647 (902) 893-5900 199 Elliott Street 10 Princess Street 14 Court Street, Pictou, NS Springhill, NS Suite 205, Truro, NS Sexual Health Centers in Northern Nova Scotia Sexual Health Center Pictou County Center for Sexual Colchester Sexual Assault Center for Cumberland County Health 80 Glenwood Drive, Truro, NS 11 Elmwood Drive , Amherst , NS side 503 South Frederick Street, New Glasgow, NS Phone 897-4366 entrance Phone 695-3366 [email protected] Phone 667-7500 [email protected] No website or facebook page available [email protected] www.pictoucountysexualhealth.com Hours of Operation are Mon. - Thur. www.cumberlandcounty.cfsh.info facebook.com/pages/pictou-county-centre-for- 9:30am – 4:30 pm facebook.com/page/Sexual-Health-Centre-for- Sexual-Health Cumberland-County Hours of Operation are Mon. -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 4 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 Land Transactions by the Province of Schedule “A” Nova Scotia pursuant to the Ministerial Notice of Parcel Registration under the Land Transaction Regulations (MLTR) for Land Registration Act the period February 13, 2009 to October 14, 2010 TAKE NOTICE that ownership of the property known as Name/Grantor Year Fishery Limited PID 20244828, located at 700 Willow Street, Truro, Type of Transaction Grant Colchester County, Nova Scotia, has been registered Location Hacketts Cove under the Land Registration Act, in whole or in part on Halifax County the basis of adverse possession, in the name of Allen Area 1195 square metres Dexter Symes. Document Number 92763250 recorded February 13, 2009 NOTICE is being provided as directed by the Registrar General of Land Titles in accordance with clause Name/Grantor Mariners Anchorage Residents 10(10)(b) of the Land Registration Administration Association Regulations. For further information, you may contact Type of Transaction Grant the lawyer for the registered owner, noted below. Location Glen Haven, Halifax County Area 192 square metres TO: The Heirs of Ernest MacKenzie or other persons Document Number 96826046 who may have an interest in the above-noted property. recorded September 21, 2010 DATED at Pictou, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, this Name/Grantor Welsford, Barbara 17th day of January, 2011. Type of Transaction Grant Location Oakland, Halifax County Ian H. MacLean Area 174 square metres -

July-August 2020 NS Lion

InThis Issue Highlights from Zone 7.......................................Pg 1 Lions Club International In Memory…………...…...….....................…...Pg. 2 District N2 DG’s Newsletter……...…………….......…........Pg.3 Canso…............................................................. Pg.4 Nova Scotia Canada A/F/R………………...........................................Pg.5 Wolfville………….............................................Pg.6 St. Margaret’s Bay..............................................Pg.7 Best Club Points……………..…….............Pg .8&9 Spring Hill 2011 & Club Standings................Pg.10 Acadia Branch Club and Bridgewater.....….Pg. 11 THE NOVA SCOTIA LION From Activity Reports…...….................Pgs. 12&13 Amherst & Kingston...............................Pgs.14 &15 Life Membership Awards……........................Pg. 16 Vol. 54 No. 1 July/August 2020 Zone 7 decided in March to do a project together, their project was to raise monies for the Special Olympics Annapolis with a goal of $2000.00 goal. The photo shows a cheque totaling $2101.58 being presented to Melissa Wade, Regional Coordinator, Special Olympics Annapolis by Zone Chair Linda Baltzer and Middleton’s King Lion George Gould. Zone Chair Linda sends out a very big thank you to all 6 clubs in Zone 7 for their contribution to this great project and for the amount they raised considering how the last half of their year went. A job well done in 2019-2020!! "In Memory of Deceased Lion's District N2" 2019 2020” Deep Brook/Waldec: Kentville: Lion Natalie Lion Rick Ball Dempsey Middleton: Eastern Passage/ Lion Holly Cowbay: MacKenzie Lion Betty Ellwanger Amherst: Lion Tom Fisher PKL John Barrett presenting a $5000 to CK grad students Cammeron Shay (right) and Truro: Cammeron Newcombe (left). Lion Albert Hatfield Aylesford: Lion Howard MacKenzie (CM) Bedford: Lion Ken Gannon The Nova Scotia Lion Digby & Area Lions Club Lion Kipper Summer of the Lake Echo club Regular Meeting 4th Wed. -

YREACH Report

O UT CO ME HIGHLIGHTS YREACH Report Number of clients registered: 464 April-June 2016 There were 131 new clients registered in this quarter. Site Highlights ● Examples of Group Settlement Support Kentville ● A YREACH funding announcement Sessions: happened on May 16th with Minister Diab announcing that the YMCA has received increased funding from the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration - Weekly Informal Conversation Groups: 6 to support newcomers in the Kentville area. A new family received a donated bike at the announcement. -Cooking Classes: 2 ● In collaboration with Acadia University in Wolfville, YREACH has been working with local refugee sponsorship groups to provide afternoon activities for children, youth and their - Social and Recreational families during the months of July and August. Activities : Female Only ● YREACH booth was set up at the New Arrivals Welcome Day in Ross Creek Centre for Arts. Community swim , weekly sports & connections with local community groups were made for help with summer language class activities. activities, Family Friday Amherst Fun night, Bowling, Potluck Bridgewater ● School Settlement: 25 ● Well attended Multicultural Potluck different schools ● 8 different awareness raising and infor- on June 28th involving community members, stakeholders and newcomer - 4 Newcomer's Club mation session were delivered in Bridge- clients. water area to build capacity of community Community members to be more welcoming and inclu- ● Examples of settlement this quarter Collaborations sive. Presentations included: include: -

330 Pictou Antigonish Highlands Profile

A NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION Ecodistrict Profile Ecological Landscape Analysis Summary Ecodistrict 330: Pictou Antigonish Highlands An objective of ecosystem-based management is to manage landscapes in as close to a natural state as possible. The intent of this approach is to promote biodiversity, sustain ecological processes, and support the long-term production of goods and services. Each of the province’s 38 ecodistricts is an ecological landscape with distinctive patterns of physical features. (Definitions of underlined terms are included in the print and electronic glossary.) This Ecological Landscape Analysis (ELA) provides detailed information on the forest and timber resources of the various landscape components of Pictou Antigonish Highlands Ecodistrict 330. The ELA also provides brief summaries of other land values, such as minerals, energy and geology, water resources, parks and protected areas, wildlife and wildlife habitat. This ecodistrict has been described as an elevated triangle separating the Northumberland Lowlands Ecodistrict 530 of Pictou County from the St. Georges Bay Ecodistrict 520 lowlands of Antigonish County. Generally, the highlands at their summit become a rolling plateau best exemplified by The Keppoch, an area once extensively settled and farmed. The elevation in the ecodistrict is usually 210 to 245 metres above sea level and rises to 300 metres at Eigg Mountain. The total area of Pictou Antigonish Highlands is 133,920 hectares. Private land ownership accounts for 75% of the ecodistrict, 24% is under provincial Crown management, and the remaining 1% includes water bodies and transportation corridors. A significant portion of the highlands was settled and cleared for farming by Scottish settlers beginning in the late 1700s with large communities at Rossfield, Browns Mountain, and on The Keppoch. -

798 TRANSPORTATION and COMMUNICATIONS 85.—Mail

798 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS 85.—Mail Subsidies and Steamship Subventions, fiscal years ended Mar. 31,1932-34. NOTE.—The figures in the following table were supplied by F. E. Bawden, Esq., Director of Steam ship Subsidies, Department of Trade and Commerce. They appear annually in the Annual Report of the Auditor General and represent the amounts paid in connection with contracts made under statutory au thority by the Department of Trade and Commerce for trade services, including the conveyance of mails. Service. 1932. 1933. Atlantic Ocean- Canada and Great Britain 802,000 535,000 Canada and South Africa 150,000 112,500 Eastern Canada and Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina 100,000 - To assist the carriage of livestock to Europe 43.739 — Pacific Ocean- British Columbia, Australia and/or China 92,400 66,000 Canada, China and Japan 988,000 659,000 Canada and New Zealand, on the Pacific 100,000 75,000 Prince Rupert, B.C., and the Queen Charlotte islands 16,800 15,447 Vancouver and the British West Indies 45,900 37,350 Vancouver and ports on Howe sound. 4,000 - Vancouver and northern ports of British Columbia 19,840 18,600 Victoria, Vancouver, way ports and Skagway 25,000 12,500 Victoria and west coast Vancouver island 12,000 11,250 British Columbia and South Africa Local Services— Baddeck and Iona 10,500 10,500 Charlottetown and Pictou 40,000 30,000 Charlottetown, Victoria and Holliday's Wharf 5,600 4,600 Dalhousie, N.B., and Carleton, Que 2,400 - Grand Manan and the mainland 33,000 24,750 Halifax and Bay St. -

1 Travel to Wolfville and Kentville, Nova Scotia, Canada, to Collect

Travel to Wolfville and Kentville, Nova Scotia, Canada, to collect Vaccinium and Related Ericaceae for USDA Plant Exploration Grant 2012 Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia AAFC Kentville, Nova Scotia Kim Hummer, Research Leader USDA ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository, Corvallis, Oregon Location and Dates of Travel Wolfville and Kentville, Nova Scotia, Canada 15 July through 20 July 20102 Objectives: To obtain cuttings/ propagules of the Vaccinium collections of Dr. Sam Vander Kloet, Professor Emeritus at Acadia University, Kentville, Nova Scotia. Executive Summary During 15 through 20 July 2012, I traveled to Nova Scotia to obtain plant material that Dr. Sam Vander Kloet, Emeritus Professor at Acadia University had obtained during his life. Acadia University Conservatory, Wolfville, had about 100 accessions of subtropical Vaccinium (blueberry) and related genera. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada had about 90 accessions of native North American Vaccinium in their field collections. On Monday 16 July through Wednesday 18 July 2012, I worked at the Herbarium and Conservatory of Acadia University working with Ruth Newell, the Curator. From Wednesday afternoon through Thursday, I worked with Dr. Andrew Jamieson, Small fruit Breeder and Geneticist, Agriculture and Agri- Food Canada. I obtained a total of 654 root and stem cuttings of the following genera: Cavendishia (62), Ceratostemma (7), Costera (1), Diogenesia (9), Disterigma (10), Macleania (25), Pernettya (13), Psammisia (7), Spyrospermum (7), and Vaccinium (513). I also obtained two accessions of seed including Vaccinium boreale (1000 count) and Fragaria vesca subsp. alba (2000 count). I obtained a Canadian phytosanitary certificate and had USDA APHIS permits and letters to bring in the Vaccinium and permissible nurserystock. -

Port Hawkesbury Looking Back

Port Hawkesbury Looking Back... CONNECTING LITERACY AND COMMUNITY Port Hawkesbury Literacy Council June 2002 Our sincere thanks to the National Literacy Secretariat, Human Resources Development Canada for providing funding for this project. Acknowledgements This book is a project of the Port Hawkesbury Literacy Council which recognized the need for relevant adult learning material that was written for Level 1 and 2 learners in our CLI Adult Learning Program. The creation of this material would not have been possible without the support of the Port Hastings Museum staff. A thank you to them for the use of their many resources. A special thank you to the Port Hawkesbury Centennial Committee for permission to use material found in their invaluable resource, A Glimpse of the Past. Thanks also to the Tamarac Education Center Library for sharing their resources. Learners, Instructors, and Tutors from the Port Hawkesbury Community Learning Initiative Levels 1 and 2 took part in the planning and piloting of this material. A sincere thanks for their interest and input. Thanks, as well, to Bob Martin of Bob Martin Photographic Studios for the use, and copies, of his collection of Port Hawkesbury photographs and to Pat MacKinnion for the use of the beautiful colour picture on the cover. Thanks as well to the staff of the Town of Port Hawkesbury for their administrative assistance; to the Port Hawkesbury Parks, Recreation and Tourism Department for their ongoing support of literacy in our area; to the members and staff of the Port Hawkesbury Literacy Council for their continued support; and to the Nova Scotia Department of Education, Adult Education Section, for their ongoing support. -

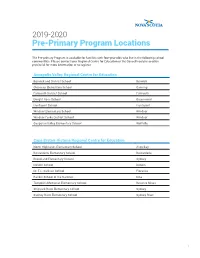

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations The Pre-primary Program is available for families with four-year-olds who live in the following school communities. Please contact your Regional Centre for Education or the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial for more information or to register. Annapolis Valley Regional Centre for Education Berwick and District School Berwick Glooscap Elementary School Canning Falmouth District School Falmouth Dwight Ross School Greenwood Hantsport School Hantsport Windsor Elementary School Windsor Windsor Forks District School Windsor Gasperau Valley Elementary School Wolfville Cape Breton-Victoria Regional Centre for Education North Highlands Elementary School Aspy Bay Boularderie Elementary School Boularderie Brookland Elementary School Sydney Donkin School Donkin Dr. T.L. Sullivan School Florence Rankin School of the Narrows Iona Tompkins Memorial Elementary School Reserve Mines Shipyard River Elementary School Sydney Sydney River Elementary School Sydney River 1 Chignecto-Central Regional Centre for Education West Colchester Consolidated School Bass River Cumberland North Academy Brookdale Great Village Elementary School Great Village Uniacke District School Mount Uniacke A.G. Baillie Memorial School New Glasgow Cobequid District Elementary School Noel Parrsboro Regional Elementary School Parrsboro Salt Springs Elementary School Pictou West Pictou Consolidated School Pictou Scotsburn Elementary School Scotsburn Tatamagouche Elementary School Tatamagouche Halifax Regional Centre for Education Sunnyside Elementary School Bedford Alderney Elementary School Dartmouth Caldwell Road Elementary School Dartmouth Hawthorn Elementary School Dartmouth John MacNeil Elementary School Dartmouth Mount Edward Elementary School Dartmouth Robert K. Turner Elementary School Dartmouth Tallahassee Community School Eastern Passage Oldfield Consolidated School Enfield Burton Ettinger Elementary School Halifax Duc d’Anville Elementary School Halifax Elizabeth Sutherland Halifax LeMarchant-St. -

Acadia Archives |

/ .r / FALL CONVOCATION FOUNDERS' DAY ACADIA UNIVERSITY 10:00 A.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 28 1972 WOLFVILLE, NOVA SCOTIA PROCESSIONAL 0 CANADA WELCOME HY DR. J. M. R. BEVERIDGE, PRESIDENT AND VICE-CHANCELLOR LA YING OF WREATHS PRAYER OF INVOCATION PRESENTATION OF ALUMNI SCHOLARSHIPS CONVOCATION FOR AWARDING OF DEGREES AND DIPLOMAS PRESIDING: DR. CHARLES B. HUGGINS, CHANCELLOR POSTGRADUATE DEGREES Master of Arts Bishop, Barbara Evelyn Leonard (English) ... .........Paradise, N.S. Wilson, Edgar Mordante (English) ........................................ Guyana Master of Science Brumbaugh, Ray Kent (Psychology) .......................... Lancaster, Pa. Haight, Caleb Barry (Mathematics) .................... North Range, N.S. Huston, Frank (Biology) ................................................ Wolfville, N.S. Schaffner, John Phinney (Chemistry) ...................... Kentville, N.S. Master of Education Atkinson, Sylvester James......... ...........................Stoney Island, NS. Grant, Frederick William.. ......... ..... .......... .................... Moncton, N.B. Hache, Alfred .................................................................. Lunenburg, N.S. Hughes, Andrew Samuel.. ..... ......................................... Wolfville, N.S. Johnston, Brian Earl......................... ......................... ...... Wolfville, N.S. Lindsay, Arthur John .............. .. ........... ................. Tatamagouche, N.S. Neve, Peter Emerson............. ........................................... St. Flore, P.Q. Steeves, Lawson Starrak. -

CANADIAN MARITIMES 2016 19 June - 17 August 2016

CANADIAN MARITIMES 2016 19 June - 17 August 2016 SMART Canadian Maritimes Caravan 2016 19 June - 17 August 2016 Wagon Masters: Carl and Gwen Hopper Assistant Wagon Masters: Mark and Linda Avey The 2016 Canadian Maritimes Caravan started and ended in Hermon, Maine, and covered over 3,000 miles in the Maritime Provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island. We started the trip with 19 rigs but unfortunately lost one in Monc- ton, New Brunswick ,due to an accident. No one was seriously injured, but we had to continue on with only 18 rigs. Some of the highlights of this trip included the Bay of Fundy with 25-foot tides, the Royal Nova Scotia International Tattoo, rides on the Bluenose II and Amoeba sailing vessels, whale watching tours, and some of the most beautiful and breathtaking scenery in the world. Some of our group even took a day trip to Labrador, while others sailed out of St. Anthony, Newfoundland, to view icebergs and whales. We enjoyed many caravan-sponsored dinners with lots of lobster and other seafood. This was an amazing trip which was made even more enjoyable by the outstanding people who traveled with us. Many thanks to all who contributed time and effort to make this a truly memorable trip. Carl & Gwen Hopper and Linda & Mark Avey 2 3 Itinerary leg dates city state/province campground 1 June 19-20 Hermon Maine Pumpkin Patch 2 June 21-23 St John New Brunswick Rockwood Park 3 June 24-26 Hopewell Cape Ponderosa Pines 4 June 27-July 1 Hammonds Plains Nova Scotia Woodhaven 5 July 2-4 Grand Pré -

Principals in Focus

APRIL 16, 19, & 20, 2012 SUMMARY REPORT Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Evaluation Process........................................................................................................................ 1 3.0 Highlights of Participant Feedback .............................................................................................. 2 4.0 Concurrent Session Descriptions ................................................................................................. 2 4.1 The Way Forward for School Improvement: From Accreditation to Learning Communities ....... 2 4.2 Emerging Professional Learning Communities ............................................................................. 3 4.3 Becoming an Effective Instructional Leader ................................................................................. 3 4.4 Nova Scotia Virtual School ............................................................................................................ 4 5.0 Town Hall ...................................................................................................................................... 4 5.1 Common Concerns ........................................................................................................................ 4 5.2 Regional Session Highlights ........................................................................................................... 5 5.2.1