Selecting Peter Robinson's Irish Emigrants*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duhallow Timetables

Cork B A Duhallow Contents For more information Route Page Route Page Rockchapel to Mallow 2 Mallow to Kilbrin 2 Rockchapel to Kanturk For online information please visit: locallinkcork.ie 3 Barraduff to Banteer 3 Donoughmore to Banteer 4 Call Bantry: 027 52727 / Main Office: 025 51454 Ballyclough to Banteer 4 Email us at: [email protected] Rockchapel to Banteer 4 Mallow to Banteer 5 Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Rockchapel to Cork 5 Kilbrin to Mallow 6 Operated By: Stuake to Mallow 6 Local Link Cork Local Link Cork Rockchapel to Kanturk 6 Council Offices 5 Main Street Guiney’s Bridge to Mallow 7 Courthouse Road Bantry Rockchapel to Tralee 7 Fermoy Co. Cork Co. Cork Castlemagner to Kanturk 8 Clonbanin to Millstreet 8 Fares: Clonbanin to Kanturk 8 Single: Return: Laharn to Mallow 9 from €1 to €10 from €2 to €17 Nadd to Kanturk 9 Rockchapel to Newmarket 10 Freemount to Kanturk 10 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Rockchapel to Rockchapel Village 10 Rockchapel to Young at Heart 11 Contact the office to find out more about our wheelchair accessible services Boherbue to Castleisland 11 Boherbue to Tralee 12 Rockchapel to Newmarket 13 Taur to Boherbue 13 Local Link Cork Timetable 1 Timetable 025 51454 Rockchapel-Boherbue-Newmarket-Kanturk to Mallow Rockchapel-Ballydesmond-Kiskeam to Kanturk Day: Monday - Friday (September to May only) Day: Tuesday ROCKCHAPEL TO MALLOW ROCKCHAPEL TO KANTURK Stops Departs Return Stops Departs Return Rockchapel (RCC) 07:35 17:05 Rockchapel (RCC) 09:30 14:10 -

Doneraile Park the Long St. Leger Connection Seamus Crowley

IRISH FORESTRY 2015, VOL. 72 Doneraile Park The long St. Leger connection Seamus Crowley The arrival of St. Legers in Ireland When Henry VIII of England decided to suppress the monasteries and break away from the Church of Rome, he gave the job of implementing the process to his “trusty and well beloved servant” Sir Anthony St. Leger of Ulcomb in Kent who was reputed to be “a wise and warie gentleman”. Sir Anthony, in his capacity as a member of the Kent Grand Jury, helped to find a “true bill” against Ann Boleyn, which allowed Henry to have her executed in 1536 – a trusty servant indeed! Having finished the job of suppressing the monasteries in England, Sir Anthony was sent to Ireland to render similar service in 1537. He supervised the dissolution of the monasteries in areas subject to the King’s writ and also succeeded in getting the Irish chieftains to accept Henry as King of Ireland. Before that the English King was described as Lord of Ireland, which gave him much less authority. Later Sir Anthony St. Leger was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and from which time on the St. Legers had a presence in Ireland. When Sir Anthony St. Leger returned to England, one of his sons, William, who later did not feature in Sir Anthony’s will, was “catered for” in Ireland and took part in both government and army. William’s son, Sir Antony St. Leger’s grandson, Sir Warham St. Leger remained in Ireland until his death in 1600. He died following a single combat engagement with Hugh Maguire of Fermanagh outside the gates of Cork. -

Cork County Grit Locations

Cork County Grit Locations North Cork Engineer's Area Location Charleville Charleville Public Car Park beside rear entrance to Library Long’s Cross, Newtownshandrum Turnpike Doneraile (Across from Park entrance) Fermoy Ballynoe GAA pitch, Fermoy Glengoura Church, Ballynoe The Bottlebank, Watergrasshill Mill Island Carpark on O’Neill Crowley Quay RC Church car park, Caslelyons The Bottlebank, Rathcormac Forestry Entrance at Castleblagh, Ballyhooley Picnic Site at Cork Road, Fermoy beyond former FCI factory Killavullen Cemetery entrance Forestry Entrance at Ballynageehy, Cork Road, Killavullen Mallow Rahan old dump, Mallow Annaleentha Church gate Community Centre, Bweeng At Old Creamery Ballyclough At bottom of Cecilstown village Gates of Council Depot, New Street, Buttevant Across from Lisgriffin Church Ballygrady Cross Liscarroll-Kilbrin Road Forge Cross on Liscarroll to Buttevant Road Liscarroll Community Centre Car Park Millstreet Glantane Cross, Knocknagree Kiskeam Graveyard entrance Kerryman’s Table, Kilcorney opposite Keim Quarry, Millstreet Crohig’s Cross, Ballydaly Adjacent to New Housing Estate at Laharn Boherbue Knocknagree O Learys Yard Boherbue Road, Fermoyle Ball Alley, Banteer Lyre Village Ballydesmond Church Rd, Opposite Council Estate Mitchelstown Araglin Cemetery entrance Mountain Barracks Cross, Araglin Ballygiblin GAA Pitch 1 Engineer's Area Location Ballyarthur Cross Roads, Mitchelstown Graigue Cross Roads, Kildorrery Vacant Galtee Factory entrance, Ballinwillin, Mitchelstown Knockanevin Church car park Glanworth Cemetery -

Strategic Development Opportunity

STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Fermoy Co. Cork FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY (AVAILABLE IN ONE OR MORE LOTS) DEVELOPMENT LAND FOR SALE SALE HIGHLIGHTS > Total site area extends to approximately 3.4 ha (8.4 acres). > Zoned Town Centre Mixed Use in the Fermoy Town Centre Development Plan. > Excellent location in the heart of Fermoy Town Centre. > Conveniently located approximately 35kms north east of Cork City Centre. > Location provides ease of access to the M8 and N72. > For sale in one or more lots. LOCATION MAP LOT 1 LOT 2 FERMOY, CO. CORK THE OPPORTUNITY DISTANCE FROM PROPERTY Selling agent Savills is delighted to offer for M8 3km sale this development opportunity situated in the heart of Fermoy town centre within N72 Adjacent walking distance of all local amenities. The Jack Lynch Tunnel & M8 29km property in its entirety extends to 3.4 ha (8.4 acres), is zoned for Town Centre development Cork City Centre 35km and is available in one or more lots. The site is Little Island 32km well located just off Main Street Fermoy with ease of access to the M8, the main Cork to Kent railway station 24km Dublin route. The opportunity now exists to Cork Airport 30km acquire a substantial development site, in one or more lots, with value-add potential in the Pairc Ui Chaoimh 25km heart of Fermoy town centre. Mallow 30km Doneraile Wildlife Park 29km LOCATION Mitchelstown 20km The subject property is located approximately 35km north east of Cork City Centre and approximately 30km east of Mallow and approximately 20km south of Mitchelstown. -

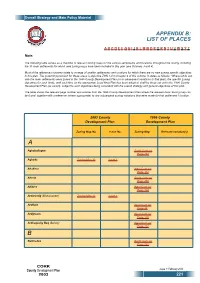

Appendix B (List of Places)

Overall Strategy and Main Policy Material APPENDIX B: LIST OF PLACES A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Note: The following table serves as a checklist of relevant zoning maps for the various settlements and locations throughout the county, including the 31 main settlements for which new zoning maps have been included in this plan (see Volumes 3 and 4). Most of the references however relate to a range of smaller settlements and locations for which there are no new zoning specific objectives in this plan. The governing provision for these areas is objective ZON 1-4 in Chapter 9 of this volume. It states as follows: “Where lands out- side the main settlements were zoned in the 1996 County Development Plan (or in subsequent variations to that plan), the specific zoning objectives for such lands, until such time as the appropriate Local Area Plan has been adopted, shall be those set out in the 1996 County Development Plan (as varied), subject to such objectives being consistent with the overall strategy and general objectives of this plan. The table shows the relevant page number and volume from the 1996 County Development Plan where the relevant basic zoning map can be found, together with a reference (where appropriate) to any subsequent zoning variations that were made for that settlement / location. 2003 County 1996 County Development Plan Development Plan Zoning Map No. Issue No. Zoning Map Relevant variation(s) A Aghabullogue South Cork vol Page 281 Aghada Zoning Map 30 Issue 1 Ahakista West Cork vol Page 112 Aherla South Cork vol Page 256 Allihies West Cork vol Page 124 Ardarostig (Bishopstown) Zoning Map 12 Issue 1 Ardfield West Cork vol Page 46 Ardgroom West Cork vol Page 126 Ardnageehy Beg (Bantry) West Cork vol Page 112 B Ballinadee South Cork vol Page 230 CORK County Development Plan Issue 1: February 2003 2003 221 Appendix B. -

Walking Trails of County Cork Brochure Cork County of Trails Walking X 1 •

Martin 086-7872372 Martin Contact: Leader Wednesdays @ 10:30 @ Wednesdays Day: & Time Meeting The Shandon Strollers Shandon The Group: Walking www.corksports.ie Cork City & Suburb Trails and Loops: ... visit walk no. Walking Trails of County Cork: • Downloads & Links & Downloads 64. Kilbarry Wood - Woodland walk with [email protected] [email protected] 33. Ballincollig Regional Park - Woodland, meadows and Email: St Brendan’s Centre-021 462813 or Ester 086-2617329 086-2617329 Ester or 462813 Centre-021 Brendan’s St Contact: Leader Contact: Alan MacNamidhe (087) 9698049 (087) MacNamidhe Alan Contact: panoramic views of surrounding countryside of the • Walking Resources Walking riverside walks along the banks of the River Lee. Mondays @ 11:00 @ Mondays Day: & Time Meeting West Cork Trails & Loops: Blackwater Valley and the Knockmealdown Mountains. details: Contact Club St Brendan’s Walking Group, The Glen The Group, Walking Brendan’s St Group: Walking • Walking Programmes & Initiatives & Programmes Walking 34. Curragheen River Walk - Amenity walk beside River great social element in the Group. Group. the in element social great • Walking trails and areas in Cork in areas and trails Walking 1. Ardnakinna Lighthouse, Rerrin Loop & West Island Loop, Curragheen. 65. Killavullen Loop - Follows along the Blackwater way and Month. Walks are usually around 8-10 km in duration and there is a a is there and duration in km 8-10 around usually are Walks Month. Tim 087 9079076 087 Tim Bere Island - Scenic looped walks through Bere Island. Contact: Leader • Walking Clubs and Groups and Clubs Walking takes in views of the Blackwater Valley region. Established in 2008; Walks take place on the 2nd Saturday of every every of Saturday 2nd the on place take Walks 2008; in Established Sundays (times vary contact Tim) contact vary (times Sundays 35. -

CEF 2021 Successful North Fermoy Organisation Project Details

CEF 2021 Successful North Fermoy Amount Partial Application Project Amount Organisation Project Details MD Applied for or Total Type Total Cost Offered Ballyhooly Tennis Club Sanitising equipment and supplies. €979.00 T 1000 or less €979.00 Fermoy €500 CDYS Fermoy 5 small, portable table top telescopes €930.00 T 1000 or less €930.00 Fermoy €650 Glenville Community Council Hot water system. €1,000.00 T 1000 or less €1,000.00 Fermoy €850 Mitchelstown Commuity Sanitising equipment and supplies. €1,000.00 T 1000 or less €1,000.00 Fermoy €500 Council Ballindangan Community Sanitising equipment and supplies commnuity €1,805.00 T 1001 or more €1,805.00 Fermoy €1,805 Council phone, newsletter and external noticeboard. Castlelyons Community Centre Sanitising equipment and supplies and 2 awnings. €2,000.00 P 1001 or more €8,050.00 Fermoy €1,000 CDYS Mitchelstown Zoom package. €3,098.00 T 1001 or more €3,098.00 Fermoy €500 Mitchelstown Community Centre T/A Mitchelstown Online booking system. €5,000.00 P 1001 or more €6,050.00 Fermoy €2,500 Lesiure Centre €8,305 Kanturk and Mallow Amount Partial Application Project Amount Organisation Project Details MD Applied for or Total Type Total Cost Offered Castlemagner Community Kanturk and Community Call. €800.00 T 1000 or less €800.00 €800 Centre Committee Mallow CDYS Youth Work Ireland Kanturk and Marquee. €649.00 T 1000 or less €649.00 €649 Mallow Mallow Duhallow Community Food Kanturk and Hot transport box. €1,000.00 P 1000 or less €1,291.50 €1,000 Services Mallow Kanturk and Irish Wheelchair Association Zoom drama classes. -

Recruitment Advertising

XX1 - V1 ����� �������� �������� ���������� ������ ������������� �� ������ ������� ������ ������� ����� ������� �������� ������� ��������������� �� �������� ����� ������� ����� ������� ��� �������� ����� DÚN LAOGHAIRE DENNEHY TIM (Knockraha AHERN (Bishopstown, Cork): O’DRISCOLL (Cork and �� ������ ������ RATHDOWN COUNTY and Millstreet) On September 28, 2016, Ballycotton): On September �������� ����� ���� �� ���� COUNCIL: Cosgrave (Acknowledgement and First peacefully, at the Mercy 28, 2016, peacefully, at the �������� ��� �� Developments are applying Anniversary): University Hospital, CLAIRE Bon Secours Hospital, sur- ������ ����� ����� ���� ���� for retention planning On Tim’s first anniversary his (nee Madden), dearly loved rounded by his loving family, permission for development wife Marie along with her wife of the late Gus and much LIAM, Woodbrook, Bishops- ������� � comprising of the family would like to thank loved mother of Bryan, town, late of Irish Lights and ������ �� ����������� ��� amalgamation of units 1 all those who sympathised Gregory, Vivienne (Dooge) Dunlops, dearly loved hus- � ������ ������� ������� (80m2) and 2 (108m2) as with them on their sad loss, and Susan (Traynor). Sadly band of the late Mairéad and ������ ���� ������� previously permitted under especially our wonderful missed by her loving family, much loved father of Lillian, ��������� An Bord Pleanála Reg. Ref. friends, neighbours and sons-in-law Diarmuid and Anthony (Tony) and Martina ���� ������ ������ ���� ���� PL06D/240677 (DLRCC Reg. family. The Holy -

A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork

Munster Technological University SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit Masters Engineering 1-1-2019 A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork Liam Dromey Cork Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://sword.cit.ie/engmas Part of the Civil Engineering Commons, and the Structural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Dromey, Liam, "A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork" (2019). Masters [online]. Available at: https://sword.cit.ie/engmas/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Engineering at SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork. Liam Dromey Supervisors: Kieran Ruane John Justin Murphy Brian O’Rourke __________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork. Ageing highway structures present a challenge throughout the developed world. The introduction of bridge management systems (BMS) allows bridge owners to assess the condition of their bridge stock and formulate bridge rehabilitation strategies under the constraints of limited budgets and resources. This research presents a decision-support system for bridge owners in the selection of the best strategy for bridge rehabilitation on a highway network. The basis of the research is an available dataset of 1,367 bridge inspection records for County Cork that has been prepared to the Eirspan BMS inspection standard and which includes bridge structure condition ratings and rehabilitation costs. -

Michael Dorgan

Michael Dorgan AUCTIONEERS & VALUERS For Sale By Private Treaty 1 Glebe Lane Glanworth Co.Cork Guide €75,000 We are delighted to present this Large uncompleted 3 bedroom family home within walking distance of Glanworths wealth of amenities. The property features an excellent layout, large garden, off street parking and is just a short drive from Fermoy and the Jack Lynch Tunnel. This property offers a superb opportunity for a First time buyer/owner occupier to add value. Viewing strictly by appointment. The above particulars are issued by Michael Dorgan, Auctioneers & Valuers on the understanding that all negotiations are conducted through them. Every care is taken in preparing particulars but the company do not hold themselves responsible for any inaccuracies. All reasonable offers will be submitted to vendors. These particulars do not form any contract for sale subsequently entered into. Michael Dorgan, Auctioneers & Valuers, Mitchelstown, Co. Cork www.daft.ie www.michaeldorgan.ie www.myhome.ie T: 025 85700 F: 025 85708 1 Glebe Lane Glanworth Co.Cork Accommodation: Entrance hallway 2.30 x 3.00 (7` 6`` x 9` 10``) Pine Staircase. Guest W.C. 2.00 x 1.60 (6` 7`` x 5` 3``) Sitting Room 4.40 x 4.20 (14` 5`` x 13` 9``) Kitchen 6.60 x 3.40 (21` 8`` x 11` 2``) Radiators Recessed lighting French doors Power points Bath room 2.10 x 2.80 (6` 11`` x 9` 2``) Toilet WHB Bath Bedroom 1 3.30 x 3.90 (10` 10`` x 12` 9``) En suite bathroom 1.05 x 2.30 (3` 5`` x 7` 6``) Bedroom 2 3.90 x 3.20 (12` 9`` x 10` 6``) Bedroom 3 The Property features side access, off street parking space and large rear garden Outside: set out in lawn. -

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED from 07/12/2019 to 13/12/2019 Under Section 34 of the A

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 07/12/2019 TO 13/12/2019 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS RECD. PROT STRU IPC LIC. WASTE LIC. 19/00781 Sybren Meijer Permission for 10/12/2019 Permission for retention for two number detached domestic No No No No Retention garages / storage buildings and for all associated site works Drom West Castletownbere Co. Cork 19/00782 Jane Tudor Permission, 10/12/2019 Retention of domestic outhouse and foundation works and floor as No No No No Permission for permitted under expired permission 06/8160 and for permission Retention to construct dwelling on same and for all associated site works Tullyglass Bandon Co. Cork 19/00783 Gerard and Deirdre Lyons Permission 10/12/2019 Alterations and extension to dwelling house, includin g ground No No No No floor extension together with minor alterations to roof windows and the material change of use of agricultural land and formation of new residential site boundary to provide an extended residential curtilage upgrade of existing waste water treatment system and for all associated site works Dreenagh Eyeries Beara Co. -

Church of Ireland Parish Registers

National Archives Church of Ireland Parish Registers SURROGATES This listing of Church of Ireland parochial records available in the National Archives is not a list of original parochial returns. Instead it is a list of transcripts, abstracts, and single returns. The Parish Searches consist of thirteen volumes of searches made in Church of Ireland parochial returns (generally baptisms, but sometimes also marriages). The searches were requested in order to ascertain whether the applicant to the Public Record Office of Ireland in the post-1908 period was entitled to an Old Age Pension based on evidence abstracted from the parochial returns then in existence in the Public Record Office of Ireland. Sometimes only one search – against a specific individual – has been recorded from a given parish. Multiple searches against various individuals in city parishes have been recorded in volume 13 and all thirteen volumes are now available for consultation on six microfilms, reference numbers: MFGS 55/1–5 and MFGS 56/1. Many of the surviving transcripts are for one individual only – for example, accessions 999/562 and 999/565 respectively, are certified copy entries in parish registers of baptisms ordered according to address, parish, diocese; or extracts from parish registers for baptismal searches. Many such extracts are for one individual in one parish only. Some of the extracts relate to a specific surname only – for example accession M 474 is a search against the surname ”Seymour” solely (with related names). Many of the transcripts relate to Church of Ireland parochial microfilms – a programme of microfilming which was carried out by the Public Record Office of Ireland in the 1950s.