The FA V Wayne Hennessey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P28.E$S Layout 1

Established 1961 Sport MONDAY, APRIL 15, 2019 Davis finally breaks out as Tiger tees off as dramatic Bayern ease past Duesseldorf 25Orioles win over host Red Sox 26 Masters final round begins 27 4-1 to reclaim top spot Salah’s strike puts Liverpool back on top City must win every game to retain title: Guardiola LONDON: Manchester City’s English midfielder Raheem Sterling (L) vies with Crystal Palace’s Ivorian striker Wilfried Zaha (R) during the English Premier League football match between Crystal Palace and Manchester City at Selhurst Park in south London yesterday. — AFP LIVERPOOL: Liverpool powered back to the top of United, Klopp’s men are convinced they can hold onto word. Liverpool threatened an early goal when Mane six days for the second leg of their Champions League the Premier League after Mohamed Salah’s stunning pole position. whipped a pin-point cross towards Salah and he fired quarter-final and a vital Premier League clash with strike clinched a 2-0 win over Chelsea yesterday. Their run-in is undoubtedly less daunting than a volley that Chelsea keeper Kepa Arrizabalaga held implications for both the title and top four race. Jurgen Klopp’s side had surrendered pole position a City’s, with Cardiff, Huddersfield and Newcastle on the well. Manchester City must win their remaining five City must overturn a 1-0 first leg deficit against few hours earlier when Manchester City won 3-1 at schedule before a potential title party against Wolves Premier League games to retain the title, insisted Pep Spurs to progress to the Champions League semi- Crystal Palace, piling pressure on the Reds to respond at Anfield. -

P20 Layout 1

Cavs cruise to Australia rout victory Afghanistan THURSDAY, MARCH 5, 201517 18 From Bradford to Napier, all for the love of Pakistan Page 19 SOUTHAMPTON: Crystal Palace’s Yannick Bolasie (top) collides with Southampton’s Maya Yoshida during the English Premier League soccer match. — AP Saints back into top-four race placed Manchester United, who crossbar. the scoring when he burst play their game in hand against Palace had already won at St through and shot tamely straight EPL results/standings Southampton 1 Newcastle late yesterday. Mary’s in the FA Cup in January at Forster. Then seconds later Zaha With the race to qualify for the and they came close to taking the skimmed a low shot against the Aston Villa 2 (Agbonlahor 22, Benteke 90-pen) West Brom 1 (Berahino 66); Hull 1 (N’Doye 15) Champions League hotting up, lead when Saints goalkeeper far post after Southampton’s for- Sunderland 1 (Rodwell 77); Southampton 1 (Mane 83) Crystal Palace 0. this was an essential victory for Fraser Forster dropped a Yannick mer Palace defender Jose Fonte English Premier League table after Tuesday’s matches (played, won, drawn, lost, goals for, goals Crystal Palace 0 Saints, who had gone three games Bolasie cross. took too long to clear. against, points): without a win or a goal. Wilfried Zaha should have tak- Those misses eventually came Chelsea 26 18 6 2 56 22 60 Newcastle 27 9 8 10 32 42 35 Eljero Elia had the first sight of en advantage, but he hesitated back to haunt Palace. Saints goal for Southampton, but he and Forster recovered to scoop pressed for the winner and Japan’s Man City 27 16 7 4 57 27 55 Crystal Palace 28 7 9 12 31 39 30 Arsenal 27 15 6 6 51 29 51 West Brom 28 7 9 12 26 36 30 SOUTHAMPTON: Southampton couldn’t keep his shot on target. -

GROUP B National Anthem Did You Know?

GROUP B England National Anthem God Save the Queen God save our gracious Queen! Long live our noble Queen! God save the Queen! Send her victorious, Happy and glorious, Long to reign over us, God save the Queen. Thy choicest gifts in store On her be pleased to pour, Long may she reign. May she defend our laws, And ever give us cause, Capital: London To sing with heart and voice, God save the Queen. Population: 53,010,000 There is only a 34 Currency: British Pound Sterling kilometre (21 mile) gap Area: 130,279km2 between England and Highest Peak: Scafell Pike (978 metres) France and the countries are connected by the Longest River: River Severn (350km) Channel Tunnel which opened in 1994. The city of London has a population of approximately Did you 12 million people, making it the largest city in all of Europe. know? English computer London is home scientist Tim There have been a to several UNESCO World Berners-Lee number of influential English Heritage Sites: The Tower of is credited with authors but perhaps the London, Royal Botanical Kew inventing the World Wide Web. most well-known is William Gardens, Westminster Palace, Shakespeare, who wrote Westminster Abbey, classics such as Romeo and St. Margaret’s Church, and Juliet, Macbeth Maritime Greenwich. and Hamlet. 14 English GROUP B football crest CURRENT SQUAD Joe Hart Manchester City FC English Jack Butland Stoke City FC Fraser Forster Southampton FC football Nathaniel Clyne Liverpool FC Leighton Baines Everton FC English Gary Cahill Chelsea FC football John Stones Everton FC team facts -

Supporting. Investing. Delivering

SEASON REVIEW 2014/15 SUPPORTING. INVESTING. DELIVERING. THE PREMIER THE LEAGUE FOOTBALL PAGES 4–7 PAGES 8–I5 INVESTING IN THE SEASON HIGHLIGHTS AND COMPETITION AND RICHARD SCUDAMORE DELIVERING CONTINUED Premier League Executive Chairman DRIVING STANDARDS SUCCESS THE PREMIER LEAGUE THE FANS “The Premier League has always worked “I never tire of saying it and the clubs hard to create the conditions for our never tire of achieving it; our top clubs to succeed. Collective decision- strategic priority is full and vibrant making and revenue distribution are stadiums. This is the third season in a critical to this. We are privileged to row that the Barclays Premier League have always had clubs who support has had occupancy in excess of 95% – this model by delivering on and off the highest in Europe. Clubs work the pitch. Throughout this Review incredibly hard to achieve this, but this you will see examples of where clubs’ season it is particularly pleasing to see investment is making a real difference an increase in away attendance, female to this competition, their fans and fans and more young people coming their communities; creating attitudes, through the turnstiles than ever before.” structures and facilities that will serve football for years to come.” THE COMMUNITIES “One of the Premier League’s proudest THE FOOTBALL achievements is the scope and “José Mourinho’s Chelsea are worthy scale of our clubs’ delivery for their Barclays Premier League Champions. communities. Seeing the impact these Their skill combined with their will to programmes can have on people really win are embodied by players like Eden drives home their importance. -

Croydon Guardian Coales Leads Striders to Victory Striders of Croydon Ended the Cross- Egory

Croydon Guardian Coales leads Striders to victory Striders of Croydon ended the cross- egory. New recruit Tom Lawson made They were led by William Pennells who country season on a winning note with an encouraging debut in third place, ran well to place 190th out of 2469 fin- a convincing victory in their inter-club while Tom Gillespie was fourth and ishers, recording a personal best 92 match against local rivals at Croydon Joseph Ibe sixth. Steph Upton was the minutes 58 seconds. His father Geoff Harriers at Lloyd Park on Saturday, first woman to finish, placing 12th over- Pennells was next home in 1 hour writes Alan Dolton. all, which was a particularly good run 40 minutes 23, and was followed by On a snow-covered six-mile course, as she had also been the first woman Steve Smith (1.44:56), Richard Myers Striders had the first four finishers. to finish at the Riddlesdown parkrun (1.45:01), Richard Tanner (1.58:53) Phil Coales led them home with a only six hours earlier. Karen Speed and Rachel Tanner (2.06:15). On the comfortable individual win, while club was the fifth woman to finish in 17th. same day, Sophia Sachedina ran Sport colleague Lee Flanagan took second Striders had six finishers in the the Hampton Court Half-Marathon in place and was first in the over-40 cat- Hastings Half-Marathon on Sunday. 1:49:52. croydonguardian.co.uk/sport Crystal Palace’s James Tomkins Robins set (left) and Huddersfield Town’s Alex Pritchard battle for the ball. -

P16sports Layout 1

Established 1961 Sport SUNDAY, MAY 6, 2018 Kiprop’s doping failure hits Houston Rockets rout Utah Jazz Holders Australia land Syria, 12Kenya’s cradle of athletics 13 113-92 to take 2-1 series lead 14 Jordan in Asian Cup draw STOKE-ON-TRENT: Stoke City’s English defender Glen Johnson (L) vies with Crystal Palace’s Ivorian striker Wilfried Zaha during the English Premier League football match between Stoke City and Crystal Palace at the Bet365 Stadium in Stoke-on- Trent, central England yesterday. — AFP West Brom stave off drop, Stoke relegated ‘The lads have given everything but we came short’ LONDON: Jake Livermore kept alive West Bromwich four, nearly five weeks. We wanted to get some pride and spent 10 seasons in the Premier League, but a run of 13 ing into positions you don’t want to be in. “We never had Albion’s slender hopes of avoiding relegation as his last- commitment back,” Moore said. games without a victory ensured that streak will come to enough. Since I came in the lads have given everything but gasp strike clinched a dramatic 1-0 win over Tottenham, “Through hard work and commitment results are com- an end. Stoke goalkeeper Jack Butland was in tears at the we came short. It is a chance to rebuild.” while Stoke were relegated after a 2-1 defeat against ing.” Since replacing the sacked Alan Pardew in early April, final whistle and City fans were just as emotional as the Palace’s win sealed their safety, making them the first Crystal Palace yesterday. -

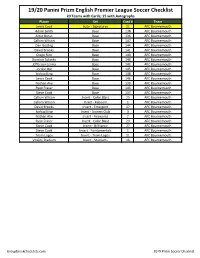

2019-20 Impeccable Premier League Soccer Checklist Hobby

2019-20 Impeccable Premier League Soccer Checklist Hobby Autographs=Yellow; Green=Silver/Gold Bars; Relic=Orange; White=Base/Metal Inserts Player Set Card # Team Print Run Callum Wilson Gold Bar - Premier League Logo 13 AFC Bournemouth 3 Harry Wilson Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 8 AFC Bournemouth 25 Joshua King Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 7 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lewis Cook Auto - Jersey Number 2 AFC Bournemouth 16 Lewis Cook Auto - Rookie Metal Signatures 9 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lewis Cook Auto - Stats 14 AFC Bournemouth 4 Lewis Cook Auto Relic - Extravagance Patch + Parallels 5 AFC Bournemouth 140 Lewis Cook Relic - Dual Materials + Parallels 10 AFC Bournemouth 130 Lewis Cook Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 6 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Jersey Number 14 AFC Bournemouth 26 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Rookie + Parallels 1 AFC Bournemouth 140 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Rookie Metal Signatures 1 AFC Bournemouth 25 Ryan Fraser Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 5 AFC Bournemouth 25 Aaron Ramsdale Metal - Rookie Metal 1 AFC Bournemouth 50 Callum Wilson Base + Parallels 9 AFC Bournemouth 130 Callum Wilson Metal - Stainless Stars 2 AFC Bournemouth 50 Diego Rico Base + Parallels 5 AFC Bournemouth 130 Harry Wilson Base + Parallels 7 AFC Bournemouth 130 Jefferson Lerma Base + Parallels 1 AFC Bournemouth 130 Joshua King Base + Parallels 2 AFC Bournemouth 130 Nathan Ake Base + Parallels 3 AFC Bournemouth 130 Nathan Ake Metal - Stainless Stars 1 AFC Bournemouth 50 Philip Billing Base + Parallels 8 AFC Bournemouth 130 Ryan Fraser Base + Parallels 4 AFC -

Minutes Template

ISLE OF ANGLESEY COUNTY COUNCIL Minutes of the Extraordinary meeting held on 18 October 2016 PRESENT: Councillor Robert G Parry OBE FRAgS (Chair) Councillor Richard Owain Jones (Vice-Chair) Councillors Lewis Davies, R Dew, Jeffrey M Evans, Jim Evans, Ann Griffith, John Griffith, K P Hughes, T Ll Hughes, Vaughan Hughes, T. Victor Hughes, W T Hughes, Llinos Medi Huws, A M Jones, Carwyn Jones, G O Jones, R Ll Jones, R Meirion Jones, Alun W Mummery, Dylan Rees, J A Roberts, Nicola Roberts, Alwyn Rowlands, Ieuan Williams and P S Rogers. IN ATTENDANCE: Chief Executive, Head of Democratic Services, Head of Corporate Transformation (for item 3), Legal Services Manager, Committee Officer (MEH). ALSO PRESENT: Mr. Gareth Hall (Consultant – Strategic Advice) (for item 5) APOLOGIES: Councillors Raymond Jones, D R Hughes, H E Jones and Dafydd Rhys Thomas. The Chair of the County Council reported that it will be the 50th Anniversary of the Aberfan disaster on the 21st October, 2016. He stated that 116 children and 28 adults were killed following a Coal Tip above the village collapsing and engulfing Pantglas Junior School and nearby houses. Members and Officers stood as a mark of respect. The Chair expressed his best wishes to Councillors H. Eifion Jones and Raymond Jones who were unwell at present. Presentation – Euro 2016 Competition The Chair of the County Council said that it was an honour and privilege to recognise and celebrate the success of the Wales Football Team during the European Championships 2016 and especially Mr. Osian Roberts, Assistant Manager of the Welsh National Team and Mr. -

2015 Topps Premier Gold Soccer Checklist

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Artur Boruc AFC Bournemouth 2 Tommy Elphick AFC Bournemouth 3 Marc Pugh AFC Bournemouth 4 Harry Arter AFC Bournemouth 5 Matt Ritchie AFC Bournemouth 6 Max Gradel AFC Bournemouth 7 Callum Wilson AFC Bournemouth 8 Theo Walcott Arsenal 9 Laurent Koscielny Arsenal 10 Mikel Arteta Arsenal 11 Aaron Ramsey Arsenal 12 Santi Cazorla Arsenal 13 Mesut Ozil Arsenal 14 Alexis Sanchez Arsenal 15 Olivier Giroud Arsenal 16 Bradley Guzan Aston Villa 17 Jordan Amavi Aston Villa 18 Micah Richards Aston Villa 19 Idrissa Gueye Aston Villa 20 Jack Grealish Aston Villa 21 Gabriel Agbonlahor Aston Villa 22 Rudy Gestede Aston Villa 23 Thibaut Courtois Chelsea 24 Branislav Ivanovic Chelsea 25 John Terry Chelsea 26 Nemanja Matic Chelsea 27 Eden Hazard Chelsea 28 Cesc Fabregas Chelsea 29 Radamel Falcao Chelsea 30 Diego Costa Chelsea 31 Julian Speroni Crystal Palace 32 Scott Dann Crystal Palace 33 Joel Ward Crystal Palace 34 Jason Puncheon Crystal Palace 35 Yannick Bolasie Crystal Palace 36 Mile Jedinak Crystal Palace 37 Wilfried Zaha Crystal Palace 38 Connor Wickham Crystal Palace 39 Tim Howard Everton 40 Leighton Baines Everton 41 Seamus Coleman Everton 42 Phil Jagielka Everton 43 Ross Barkley Everton 44 John Stones Everton 45 Romelu Lukaku Everton 46 Kasper Schmeichel Leicester City 47 Wes Morgan Leicester City 48 Robert Huth Leicester City 49 Riyad Mahrez Leicester City 50 Jeff Schlupp Leicester City 51 Shinji Okazaki Leicester City 52 Jamie Vardy Leicester City 53 Simon Mignolet Liverpool FC 54 Martin Skrtel Liverpool FC 55 Nathaniel Clyne Liverpool -

Download Panini Colourable Football Stickers

2 1 1.89M 82KG GER BERND LENO D.O.B. 04-03-92 | Bietighem-Bissingen 7 10 1.80M 71KG GER MESUT ÖZIL D.O.B. 15-10-88 | Gelsenkirchen 3 14 1.87M 80KG GAB PIERRE-EMERICK AUBAMEYANG D.O.B. 18-06-89 | Laval (France) 10 1 1.88M 85KG ENG HG TOM HEATON D.O.B. 15-04-86 | Chester 5 40 1.96M 77KG ENG HG TYRONE MINGS D.O.B. 13-03-93 | Bath 1 7 1.78M 68KG SCO JOHN McGINN D.O.B. 18-10-94 | Glasgow 8 5 1.80M 75KG NED HG NATHAN AKÉ D.O.B. 18-02-95 | Den Haag 4 24 1.63M 70KG SCO RYAN FRASER D.O.B. 24-02-94 | Aberdeen 5 13 1.80M 66KG ENG HG CALLUM WILSON D.O.B. 27-02-92 | Coventry 3 1 1.84M 82KG AUS MAT RYAN D.O.B. 08-04-92 | Plumpton 3 13 1.81M 71KG GER PASCAL GROß D.O.B. 15-06-91 | Mannheim 4 18 1.74M 68KG AUS HG AARON MOOY D.O.B. 15-09-90 | Sydney 4 1 1.91M 76KG ENG HG NICK POPE D.O.B. 19-04-92 | Soham 4 5 1.85M 81KG ENG HG JAMES TARKOWSKI D.O.B. 19-11-92 | Manchester 4 7 1.86M 78KG ICL JÓHANN GUDMUNDSSON D.O.B. 27-10-90 | Reykjavik 2 1 1.86M 88KG ESP KEPA ARRIZABALAGA D.O.B. 03-10-94 | Ondarroa 1 19 1.78M 70KG ENG MASON MOUNT D.O.B. -

2019 Panini Prizm Soccer Checklist

19/20 Panini Prizm English Premier League Soccer Checklist 20 Teams with Cards; 15 with Autographs Player Set Card # Team Lewis Cook Auto - Signatures 21 AFC Bournemouth Adam Smith Base 138 AFC Bournemouth Artur Boruc Base 136 AFC Bournemouth Callum Wilson Base 147 AFC Bournemouth Dan Gosling Base 144 AFC Bournemouth David Brooks Base 141 AFC Bournemouth Diego Rico Base 140 AFC Bournemouth Dominic Solanke Base 149 AFC Bournemouth Jefferson Lerma Base 142 AFC Bournemouth Jordon Ibe Base 145 AFC Bournemouth Joshua King Base 148 AFC Bournemouth Lewis Cook Base 146 AFC Bournemouth Nathan Ake Base 139 AFC Bournemouth Ryan Fraser Base 143 AFC Bournemouth Steve Cook Base 137 AFC Bournemouth Callum Wilson Insert - Color Blast 25 AFC Bournemouth Callum Wilson Insert - Kaboom 1 AFC Bournemouth David Brooks Insert - Emergent 17 AFC Bournemouth Joshua King Insert - Scorers Club 3 AFC Bournemouth Nathan Ake Insert - Fireworks 7 AFC Bournemouth Ryan Fraser Insert - Color Blast 23 AFC Bournemouth Steve Cook Insert - Brilliance 27 AFC Bournemouth Steve Cook Insert - Fundamentals 1 AFC Bournemouth Team Logos Insert - Team Logos 11 AFC Bournemouth Vitality Stadium Insert - Stadiums 16 AFC Bournemouth Groupbreakchecklists.com 2019 Prizm Soccer Checklist Diego Rico Base 140 AFC Bournemouth David Seaman Auto - Flashback 5 Arsenal Dennis Bergkamp Auto - Club Legends Signatures 3 Arsenal Dennis Bergkamp Auto - Dual Player Signatures 3 Arsenal Freddie Ljungberg Auto - Club Legends Signatures 6 Arsenal Robert Pires Auto - Flashback 9 Arsenal Robin van Persie -

P19 W 5 Layout 1

THURSDAY, JUNE 16, 2016 19 Bale and brawl fears stalk England in Lens CHANTILLY: England face the twin threats of a dis- hand on Saturday when Russia’s fans charged their “Aaron Ramsey, another player who’s very talent- qualification warning if their fans misbehave and a English counterparts at the final whistle, but they are ed. So we can’t just put all our focus on Gareth and FAN FERVOR super-motivated Gareth Bale ahead of their Euro 2016 doing their best to deflect attention from the issue. then get sucker-punched by one of their other good showdown with neighbors Wales in Lens today. The “The scenes weren’t nice to see at the end of the players.” Bale raised the temperature even before his bloody clashes between rival fans that marred game, but the people in charge will be dealing with team’s meeting with Slovakia, saying that England England’s opening 1-1 draw with Russia in Marseille at that,” said left-back Ryan Bertrand. “big themselves up before they’ve done anything” the weekend left Roy Hodgson’s side facing the threat Of equal concern to Hodgson will be the danger and that Wales play with “more passion and pride”. It of elimination from European governing body UEFA. posed by Real Madrid forward Bale, whose stunning drew a rebuke from Hodgson, who described the England midfielder Adam Lallana said that such an 25-yard free-kick against Slovakia in Bordeaux set remarks as “disrespectful”, but Bale is standing by outcome would be “devastating” and Hodgson and Wales on their way to a 2-1 win.