Interview with Dr. Ken Ravizza & Cindra Kamphoff on the High Performance Mindset Podcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feting Papi Simply Good Manners

FLORIDA’S BEST NEWSPAPER tampabay.com THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2016 Feting Papi simply good manners ST. PETERSBURG Now, about Papi-palooza … the British officers at Yorktown? — The Rays are now “Here’s why it’s a wonderful thing Whoever started this farewell stuff, planning to honor to do,” Rossi said. “When you host I’d like to give them a piece of my mind. David Ortiz with someone, they’re in your house, so you You know, right after I eat another piece more than a video have to treat them well. It always reflects of the farewell cake, if there is one. tribute Sunday. well on you. You have to cowboy up Does Ortiz really rise to the level of You’re on the float and you honor the person.” a Cal Ripken, Derek Jeter or Mariano MARTIN committee. Hey, wasn’t “Cowboy Up” the 2004 Rivera, who have been honored with FENNELLY Relax. They’re not world champion Red Sox’s slogan? Trop ceremonies and gifts? mfennelly@ going to be naming Back to Etiquette Central. Also, the dude beat the Rays’ brains tampabay.com a catwalk for him or Etiquette expert in during his career and sometimes anything. Patricia Rossi stopped to watch. Ortiz has 34 homers But it will be more than originally says it reflects and 88 RBIs at the Trop, more than any planned. Or was kind of planned, well on the visiting player. preliminary like. Now a gift or gifts will Rays to honor Everywhere you look, Ortiz has been be involved. David Ortiz. -

San Francisco Giants Weekly Notes: April 13-19

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS WEEKLY NOTES: APRIL 13-19 Oracle Park 24 Willie Mays Plaza San Francisco, CA 94107 Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com sfgigantes.com giantspressbox.com @SFGiants @SFGigantes @SFGiantsMedia NEWS & NOTES RADIO & TV THIS WEEK The Giants have created sfgiants.com/ Last Friday, Sony and the MLBPA launched fans/resource-center as a destination for MLB The Show Players League, a 30-player updates regarding the 2020 baseball sea- eSports league that will run for approxi- son as well as a place to find resources that mately three weeks. OF Hunter Pence will Monday - April 13 are being offered throughout our commu- represent the Giants. For more info, see nities during this difficult time. page two . 7:35 a.m. - Mike Krukow Fans interested in the weekly re-broadcast After crowning a fan-favorite Giant from joins Murph & Mac of classic Giants games can find a schedule the 1990-2009 era, IF Brandon Crawford 5 p.m. - Gabe Kapler for upcoming broadcasts at sfgiants.com/ has turned his sights to finding out which joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks fans/broadcasts cereal is the best. See which cereal won Tuesday - April 14 his CerealWars bracket 7:35 a.m. - Duane Kuiper joins Murph & Mac THIS WEEK IN GIANTS HISTORY 4:30 p.m. - Dave Flemming joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks APR OF Barry Bonds hit APR On Opening Day at APR Two of the NL’s top his 661st home run, the Polo Grounds, pitchers battled it Wednesday - April 15 13 passing Willie Mays 16 Mel Ott hit his 511th 18 out in San Francis- 7:35 a.m. -

On the Field at Kauffman Stadium Before the May 13Th Game Between

On the field at Kauffman Stadium before the May 13th game between the Kansas City Royals and Colorado Rockies I was looking for Rene Lachemann to tell him that one of his former teammates wanted to see him. But Rene was not around, so I began asking different Rockies players and staff if they had seen Mr. Lachemann. All of them responded with the same reply, “You will hear him before you see him.” Soon it was discovered what they meant as the bench coach of the Rockies made his way up from under the stadium where he had been working with one of the catchers, and his booming voice could be heard. This voice has been heard by many major league and minor league players for many years as Rene Lachemann has managed and coached and trained these players in the finer points of the game. Rene was born in Los Angeles California and is the youngest of three brothers to have long careers in professional baseball. Rene served as a batboy for the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1959 to 1962, went to the University of California and was signed by the Kansas City Athletics in 1964 as a catcher. He played for the KC A’s in 1965 and 1966 and moved with the team to Oakland appearing in games in 1968. He began managing in the Oakland minor leagues in 1973 spending 5 seasons in the A’s system before going to the Seattle Mariners organization. He took his first major league managers job in 1981 with the Mariners succeeding Maury Wills, and led the M’s from 1981-1983. -

2020 Topps Heritage Checklist Baseball

2020 Topps Heritage Baseball Checklist Does not include Unnannounced Cards; Orange = Auto; Green = Relic; Yellow = Base Rookie Player Set Card # Team Mike Trout Auto - 1971 Topps Super Boxloader 5 Angels Mike Trout Auto - Real One ROA-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto - Real One Dual Player RODA-TO Angels Mike Trout Auto Relic - Clubhouse Relic CCAR-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto Relic - Clubhouse Relic Dual Player CCDAR-TO Angels Shohei Ohtani Auto - Real One ROA-SO Angels Shohei Ohtani Auto - Real One Dual Player RODA-TO Angels Shohei Ohtani Auto Relic - Clubhouse Relic Dual Player CCDAR-TO Angels Albert Pujols Relic - Clubhouse Collection CCR-AP Angels Mike Trout Relic - 1971 Mint 71M-MT Angels Mike Trout Relic - Clubhouse Collection CCR-MT Angels Shohei Ohtani Relic - 1971 Mint 71M-SO Angels Shohei Ohtani Relic - Clubhouse Collection CCR-SO Angels Albert Pujols Base 78 Angels Albert Pujols Base Chrome THC-78 Angels Albert Pujols Insert - Base French 1 78 Angels Albert Pujols Insert - Base Mini 78 Angels Andrelton Simmons Base 360 Angels Andrelton Simmons Base Chrome Spring (Mega Box Only) THC-360 Angels Andrew Heaney Base 318 Angels Andrew Heaney Insert - Base French III 318 Angels Cam Bedrosian Base 211 Angels Cam Bedrosian Insert - Base French 1 211 Angels David Fletcher Base Chrome Spring (Mega Box Only) THC-485 Angels David Fletcher Base High Number SP 485 Angels Dylan Bundy Base 77 Angels Dylan Bundy Insert - Base French 1 77 Angels Griffin Canning Base 214 Angels Griffin Canning Insert - Base French 1 214 Angels Hansel Robles Base 375 Angels -

LINE DRIVES the NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASEBALL WRITERS NEWSLETTER (Volume 48, No

LINE DRIVES THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASEBALL WRITERS NEWSLETTER (Volume 48, No. 3, Apr. 17, 2009) The President’s Message By NCBWA President Joe Dier NCBWA Membership: With the 2008-09 hoops season now in the record books, the collegiate spotlight is focusing more closely on the nation’s baseball diamonds. Though we’re heading into the final month of the season, there are still plenty of twists and turns ahead on the road to Omaha and the 2009 NCAA College World Series. The NCAA will soon be announcing details of next month’s tournament selection announcements naming the regional host sites (May 24) and the 64-team tournament field (May 25). To date, four different teams have claimed the top spot in the NCBWA’s national Division I polls --- Arizona State, Georgia, LSU, and North Carolina. Several other teams have graced the No. 1 position in other national polls. The NCAA’s mid-April RPI listing has Cal State Fullerton leading the 301-team pack, with 19 teams sporting 25-win records through games of April 12. For the record, New Mexico State tops the wins list with a 30-6 mark. As the conference races heat up from coast to coast, the NCBWA will begin the process for naming its All- America teams and the Divk Howser Trophy (see below). We will have a form going out to conference offices and Division I independents in coming days. Last year’s NCBWA-selected team included 56 outstanding baseball athletes, and we want to have the names of all deserving players on the table for consideration for this year’s awards. -

Here Al Lang Stadium Become Lifelong Readers

RWTRCover.indd 1 4/30/12 4:15 PM Newspaper in Education The Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education (NIE) program is a With our baseball season in full swing, the Rays have teamed up with cooperative effort between schools the Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education program to create a and the Times to promote the lineup of free summer reading fun. Our goals are to encourage you use of newspapers in print and to read more this summer and to visit the library regularly before you electronic form as educational return to school this fall. If we succeed in our efforts, then you, too, resources. will succeed as part of our Read Your Way to the Ballpark program. By reading books this summer, elementary school students in grades Since the mid-1970s, NIE has provided schools with class sets three through five in Citrus, Hernando, Hillsborough, Manatee, Pasco of the Times, plus our award-winning original curriculum, at and Pinellas counties can circle the bases – first, second, third and no cost to teachers or schools. With ever-shrinking school home – and collect prizes as they go. Make it all the way around to budgets, the newspaper has become an invaluable tool to home and the ultimate reward is a ticket to see the red-hot Rays in teachers. In the Tampa Bay area, the Times provides more action at Tropicana Field this season. than 5 million free newspapers and electronic licenses for teachers to use in their classrooms every school year. Check out this insert and you’ll see what our players have to say about reading. -

Aplicarían En LMB Castigos

Viernes 18 de Enero de 2013 aCCIÓN EXPRESO 5C TieneDESTACAN R.A. DICKEY Y RYANUSA BRAUN su novena Especial / EXPRESO Especial El equipo de Estados Unidos 13 lanzadores y dos receptores, Jonathan Lucroy, Milwaukee. Karim García corre el riesgo de ser castigado si juega el Clásico Mundial. publicó su lista de peloteros pa ra el 2 0 de febrero. L a pl a nt i l l a “He hablado con todos estos del equipo de Estados Unidos, peloteros y sentí una gran emo- La Liga Mexicana de Verano ratifi có su postura de no para el Clásico Mundial, por posición, es la siguiente: ción de su parte por representar faltándole solamente uno de Lanzadores: Dickey, Toron- a Estados Unidos en el Clásico dejar jugar en el Clásico a peloteros to; Derek Holland, Texas; Craig Mundial de Beisbol”, dijo el mana- los 28 permitidos Kimbrel y Kris Medlen, Atlanta; ger de estadounidense, Joe Torre. Chris Perez y Vinnie Pestaño, “Comparto su emoción y espero DURHAM.- Los jardineros Cleveland; Glen Perkins, Min- con ansias el estar al frente de este Ryan Braun de Milwaukee, nesota; Ryan Vogelsong y Jere- talentoso grupo en marzo”. Giancarlo Stanton de Miami y my Affeldt, San Francisco; Hea- El cuerpo de entrenadores que Aplicarían en Adam Jones de Baltimore y el ga- th Bell, Arizona; Mitchell Boggs, estará junto a Torre en el Clásico nador del Cy Young R.A. Dickey, San Luis; Steve Cishek, Miami; incluye a Larry Bowa (banca), recién cambiado a Toronto, enca- Tim Collins, Kansas City y Luke Marcel Lachemann (bullpen/pi- bezan la plantilla provisional de Gregerson, San Diego. -

2009 Draysbay Season Preview

DRaysBay Season Preview 2009 1 DRaysBay Season Preview 2009 DRAYSBAY 09 Season Preview ________________________________________________________________________ CHANGE GONNA COME BY MARC NORMANDIN ................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION BY R.J. ANDERSON ....................................................................................... 8 DUMPING THE CLICHÉS BY R.J. ANDERSON....................................................................... 9 THE MAGNIFICENT 10 BY TOMMY RANCEL ....................................................................... 14 COMMUNITY PROJECTIONS..................................................................................................... 19 MAJOR LEAGUE TYPES............................................................................................................... 21 WILLY AYBAR UTL .......................................................................................................................... 21 GRANT BALFOUR RHP...................................................................................................................... 21 JASON BARTLETT SS......................................................................................................................... 21 CHAD BRADFORD RHP ..................................................................................................................... 22 PAT BURRELL DH/OF...................................................................................................................... -

Rays Trade Evan Longoria to Giants St

For Immediate Release December 20, 2017 RAYS TRADE EVAN LONGORIA TO GIANTS ST. PETERSBURG, Fla.—The Tampa Bay Rays have traded third baseman Evan Longoria and cash considerations to the San Francisco Giants in exchange for outfielderDenard Span, infielderChristian Arroyo, minor league left-handed pitcher Matt Krook and minor league right-handed pitcher Stephen Woods Jr. Longoria, 32, departs as the longest-tenured player in franchise history, after spending nearly 10 seasons in a Rays uniform. He is the club’s all-time leader with 1,435 games played, 261 home runs, 892 runs batted in, 338 doubles, 618 extra-base hits, 780 runs scored, 569 walks and 2,630 total bases. Of the 30 postseason games in Rays history, all 30 have featured Longoria in the starting lineup at third base. “Evan is our greatest Ray. For a decade, he’s been at the center of all of our successes, and it’s a very emotional parting for us all,” said Principal Owner Stuart Sternberg. “I speak for our entire organization in wishing Evan and his wonderful family our absolute best.” Longoria collected many awards over the course of his Rays career. In 2008, he was unanimously voted as the American League Rookie of the Year by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, becoming the first Ray to win a national BBWAA award. He was selected as an American League All-Star in each of his first three seasons (2008, 2009, 2010). In 2009, he won the Silver Slugger Award for AL third basemen. In November, Longoria earned his club-record third Rawlings AL Gold Glove Award, after winning the honor in 2009 and 2010. -

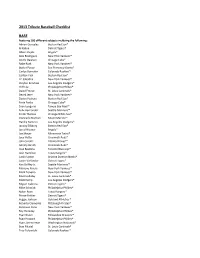

2013 Tribute Baseball Checklist BASE

2013 Tribute Baseball Checklist BASE Featurng 100 different subjects inclduing the following: Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® Al Kaline Detroit Tigers® Albert Pujols Angels® Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® Babe Ruth New York Yankees® Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® Carlos Gonzalez Colorado Rockies™ Carlton Fisk Boston Red Sox® CC Sabathia New York Yankees® Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® Cliff Lee Philadelphia Phillies® David Freese St. Louis Cardinals® Derek Jeter New York Yankees® Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® Ernie Banks Chicago Cubs® Evan Longoria Tampa Bay Rays™ Felix Hernandez Seattle Mariners™ Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® Giancarlo Stanton Miami Marlins™ Hanley Ramirez Los Angeles Dodgers® Jacoby Ellsbury Boston Red Sox® Jered Weaver Angels® Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® Jose Bautista Toronto Blue Jays® Josh Hamilton Texas Rangers® Justin Upton Arizona Diamondbacks® Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners™ Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® Mark Teixeira New York Yankees® Matt Holliday St. Louis Cardinals® Matt Kemp Los Angeles Dodgers® Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® Nolan Ryan Texas Rangers® Prince Fielder Detroit Tigers® Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ Roberto Clemente Pittsburgh Pirates® Robinson Cano New York Yankees® Roy Halladay Philadelphia Phillies® Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ Ryan Howard Philadelphia Phillies® Ryan Zimmerman Washington Nationals® Stan Musial St. Louis Cardinals® Troy Tulowitzki Colorado Rockies™ Willie Mays San Francisco Giants® AUTOGRAPHS On-Card Autographs At least 150 different cards including the following: Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® Albert Pujols Angels® Albert Belle Cleveland Indians® Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® Bob Gibson St. -

Today's Starting Lineups

TAMPA BAY RAYS (6-5) at BOSTON RED SOX (5-5) Game #11 ● Saturday, April 15, 2017 ● Fenway Park, Boston, MA TAMPA BAY RAYS AVG HR RBI PLAYER POS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AB R H RBI .325 2 8 20-Steven Souza Jr. RF .200 1 2 18-Peter Bourjos LF .225 2 5 3-Evan Longoria 3B .273 1 2 8-Rickie Weeks Jr. DH .172 0 4 33-Derek Norris C .333 3 10 7-Logan Morrison L 1B .235 0 0 29-Daniel Robertson 2B .209 0 0 39-Kevin Kiermaier L CF .167 0 0 1-Tim Beckham SS R H E LOB PITCHERS DEC IP H R ER BB SO HR WP HB P/S GAME DATA 23-RHP Jake Odorizzi (1-1, 4.50) Official Scorer: Chaz Scoggins 1st Pitch: Temp: G ame Time: Attendance: 0-Mallex Smith, OF* 15-Rocco Baldelli (1st Base) 29-Daniel Robertson, INF 44-Jamie Nelson (Coach) TB Bench TB Bullpen 1-Tim Beckham, INF 16-Kevin Cash (Manager) 30-Erasmo Ramírez, RHP 45-Jesús Sucre, C 2-Shane Peterson, OF 17-Jumbo Díaz, RHP 31-Xavier Cedeño, LHP 48-Jim Hickey (Pitching) Left Left 3-Evan Longoria, 3B 18-Peter Bourjos, OF 33-Derek Norris, C 49-Tommy Hunter, RHP 2-Shane Peterson 31-Xavier Cedeño 4-Blake Snell, LHP 20-Steven Souza Jr., OF 35-Matt Andriese, RHP 50-Austin Pruitt, RHP 10-Corey Dickerson Right 5-Matt Duffy, INF* 22-Chris Archer, RHP 37-Alex Colomé, RHP 51-Chad Mottola (Hitting) 13-Brad Miller 6-Tom Foley (Bench) 23-Jake Odorizzi, RHP 38-Shawn Tolleson, RHP^ 53-Alex Cobb, RHP 17-Jumbo Díaz 7-Logan Morrison, 1B 24-Nathan Eovaldi, RHP^ 39-Kevin Kiermaier, CF 54-Kevin Gadea, RHP^ Right 30-Erasmo Ramírez 8-Rickie Weeks Jr., INF 25-Charlie Montoyo (3rd Base) 40-Wilson Ramos, C^ 45-Jesús Sucre 37-Alex Colomé -

November 8, 2011 2012 Topps Museum Collection Baseball Page

November 8, 2011 2012 Topps Museum Collection Baseball Base Cards 1 Jeremy Hellickson Tampa Bay Rays™ 51 Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® 2 Albert Pujols St. Louis Cardinals® 52 Drew Stubbs Cincinnati Reds® 3 Carlos Santana Cleveland Indians® 53 Lou Brock St. Louis Cardinals® 4 Jay Bruce Cincinnati Reds® 54 Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® 5 Don Mattingly New York Yankees® 55 David Price Tampa Bay Rays™ 6 Justin Upton Arizona Diamondbacks® 56 Jered Weaver Angels® 7 Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® 57 Neftali Feliz Texas Rangers® 8 Stan Musial St. Louis Cardinals® 58 Cliff Lee Philadelphia Phillies® 9 Cole Hamels Philadelphia Phillies® 59 Josh Hamilton Texas Rangers® 10 Dan Haren Angels® 60 Carlton Fisk Chicago White Sox® 11 Carl Crawford Boston Red Sox® 61 Ian Kinsler Texas Rangers® 12 Cal Ripken Baltimore Orioles® 62 Roberto Alomar Toronto Blue Jays® 13 Nolan Ryan New York Mets® 63 Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ 14 Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® 64 Roy Halladay Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Derek Jeter New York Yankees® 65 Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® 16 Prince Fielder Milwaukee Brewers™ 66 Andrew McCutchen Pittsburgh Pirates® 17 Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® 67 Victor Martinez Detroit Tigers® 18 Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® 68 Julio Teheran Atlanta Braves™ 19 Ryne Sandberg Chicago Cubs® 69 Felix Hernandez Seattle Mariners™ 20 Matt Holliday St. Louis Cardinals® 70 Ty Cobb Detroit Tigers® 21 Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® 71 Willie Mays San Francisco Giants® 22 Lou Gehrig New York Yankees® 72 Hanley Ramirez Miami Marlins™ 23 Tony Gwynn San